Genealogy is fascinating because of all the stories you uncover that you could not possibly have made up. I have been working on a multi-generation family genealogy, and by the time I reached the youngest grandchildren of the tenth child of a couple who married in Providence in 1800, I thought there would be no more surprises—but then I found Stella Stafford and her Romanichals.

If you lived in Rhode Island in the late 1800s and the early 1900s, especially if you lived in a city, you would have occasionally seen Roma people, then commonly known by the pejorative term Gypsies, traveling from place to place in their caravans with their horses. Most of them came from England, members of a group called the Romanichals or Travelers. Their olive skin, the brightly colored clothing of the women, and their colorful wagons made them seem exotic, but they spoke English (in addition to their Roma dialect) and worshiped in Protestant churches.

Most of the Romanichals in New England were members of the interrelated Stanley, Hicks, Cooper, Guy, Smith, Small, Boswell, and Wells families who had immigrated to the United States, most in large family groups, in the mid-19th century. The primary occupation of the men was selling horses they brought in from Canada or the West. In the days before automobiles, horses were a commodity much in demand. The Romanichals who operated stables in Providence, Worcester, Holyoke, Fall River, and Somerville developed a reputation for providing good horses at competitive prices. Two other traditional Roma skills, telling fortunes and making and selling baskets, provided additional income.

Albert Thomas Sinclair, a well-to-do Boston lawyer whose avocation was the study of the Roma language, spent time with many of the Romanichals in the late 19th century. At an encampment on Mount Desert Island, Maine, in 1880, and in Somerville, Massachusetts, in 1882, Sinclair met members of the Stanley and Cooper families. He described Cornelius Cooper, 27 in 1880, as “strong and handsomely built, six feet in height, black hair and eyes, beautiful teeth, and complexion not very dark.” Richard Stanley, 40, was “not quite as tall as Cornelius, but darker, and pitted with the small pox.” Sinclair added, “Both of these men had extraordinary muscular development and were fine-looking, polite, agreeable, bright, and witty.” He described Cornelius Cooper’s wife Charlotte (who was Richard Stanley’s daughter), as “a pretty young woman, rather delicately formed, and quite lady-like. She was dark complexioned, dressed in gaudy colors and looked the real Gypsy.” Her younger sister Cecilia, then 17, was a “strikingly beautiful girl, both in face and figure, with dimples and clear red and white but dark complexion,” and was “retiring and modest in her manner.”[1]

Stella Stafford, the great-granddaughter of the couple who married in Providence in 1800, was the daughter of a Central Falls police officer. In the summer of 1890, when she was 17, Stella fell in love with a Romanichal named Solomon Hicks. At the time, Stella lived with her parents on Railroad Street in Central Falls. Sol, as he was called, was also 17, and like all the young men in his family, he was a horse dealer-in-training. Marriage between first-generation Romanichals and “gorgie,” or non-Roma, was rare, because of distrust on both sides. How Sol and Stella met can only be imagined, but it does not take too much imagination to guess the reaction both sets of parents had to this liaison. Still, Stella and Sol persevered, and they were married in Lincoln on September 23, 1890, by the Reverend James H. Lyon, pastor of the Central Falls Congregational Church.[2]

The Roma, who originated in northern India almost a thousand years ago, are one of the most persecuted ethnic groups on Earth. They were enslaved for centuries in eastern Europe, transported to the colony of Virginia as indentured servants by the Cromwell government in the 1640s, and burned at the stake in Scotland. More than 70% of the Roma in German-occupied countries died in the Holocaust.[3] On August 10, 2012, Human Rights Watch condemned France’s “renewed efforts to shut down Roma camps and remove Eastern European Roma from the country” in violation of European Union rules on freedom of movement and international human rights law. In April of 2015, the Associated Press reported that “Spanish groups representing Gypsies opened a campaign to remove a reference to them as ‘swindlers’ from the world’s benchmark Spanish dictionary.”[4] In Italy, on May 10, 2017, three Gypsy sisters were burned alive when someone set fire to their family’s camper in a parking lot on the outskirts of Rome.[5]

Compared to the historical persecution they suffered, the treatment of Romanichals in southern New England in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was mild, but the attitude many people had toward them can seem shocking to modern sensibilities. It was an era in which overt racism was socially acceptable. Many people considered Roma inferior, ignorant, and genetically disposed to thievery.

To be sure, some newspaper stories were benign, treating the Roma merely as a curiosity. On July 9, 1913, a correspondent for Providence’s Evening Bulletin reported that “The village of Phenix was thrown into a fever of excitement yesterday when a band of gypsies of the Stanley tribe, with four wagons, drew up in Phenix village where they halted for refreshments and incidentally gathered in a lot of small change by telling fortunes. Nearly all the village turned out to see what all the commotion was, being attracted by the scampering of small children who thronged about the wagons exchanging banter with the gypsy children. After a two hours wait the tribe drove away and encamped for the night near Hope, enroute for Danielson, Conn.”[6]

Other newspaper reports were more explicit in their use of ethnic stereotypes. On April 28, 1870, the Evening Bulletin warned its readers in a front-page story that “A band of roving gypsies, claiming to have come from Philadelphia, have been infesting different parts of our state lately, to the great discomfort of our citizens. Last week they visited Johnston, and camped out on what is known as the Plain Farm, near Rocky Hill, where they made themselves generally offensive to the people of that vicinity by stealing, burning fences, cutting down trees, turning their horses into lots, &c., till forbearance ceased to be a virtue, when constable Carrol, of Johnston, drove them out of town. Then they settled in North Providence, on the Chalkstone Road, between Dyerville and Manton, where they still have their headquarters, and whence they travel in different directions, trading horses, telling fortunes, and adding to their worldly goods in various ways not considered strictly honest. . . The gypsy camp is composed of six men, four women, and a dozen or fifteen children, and our citizens should keep a sharp look out for them . . .” The article added that a widow named Mary Pierce, of Willow Street, refusing to have her fortune told, was “soothed into unconsciousness” and her rent money stolen.[7]

Constable Carrol was still at work in 1884. The Evening Bulletin reported on September 22 of that year that “Town Sergeant Carrol cleaned out a gypsy encampment a day or two ago from Neutaconkanut Hill, where they were going to settle down for the fall. The gypsies of today are getting more and more like ordinary, unromantic tramps and vagabonds and less and less like the weird eastern race who used to be drowned and hanged in Scotland a little over two hundred years ago.”[8]

In the Evening Bulletin edition for April 14, 1883, the Wanskuck correspondent managed to insult two ethnic groups simultaneously, writing, “There is a gypsy camp in the woods on Mineral Spring pike. The gypsies have a strong resemblance to vagrant children of sunny Italy, and the name nowadays appears to be more an indiscriminate designation for a motley gathering of alien wanderers than the designation of a distinct race or nation.”[9]

Underlying prejudices were reinforced by alleged experts such as Professor W. H. Bailey of Yale University, who on February 14, 1912, lectured in Cranston on “tramps of all kinds.” He told his audience at the Peoples’ Free Baptist Church in Auburn that gypsies “stop near water with their horses. They steal and live off the country. Three years ago, when I was near Lake George, there were many of them going from fair to fair, and I never saw one of them work. The boys were expert pickpockets and the children were uneducated. There are few real gypsies in this country who speak the Romany language . . . . How did tramps become tramps? Some were born that way in the gypsy camps . . . .”[10]

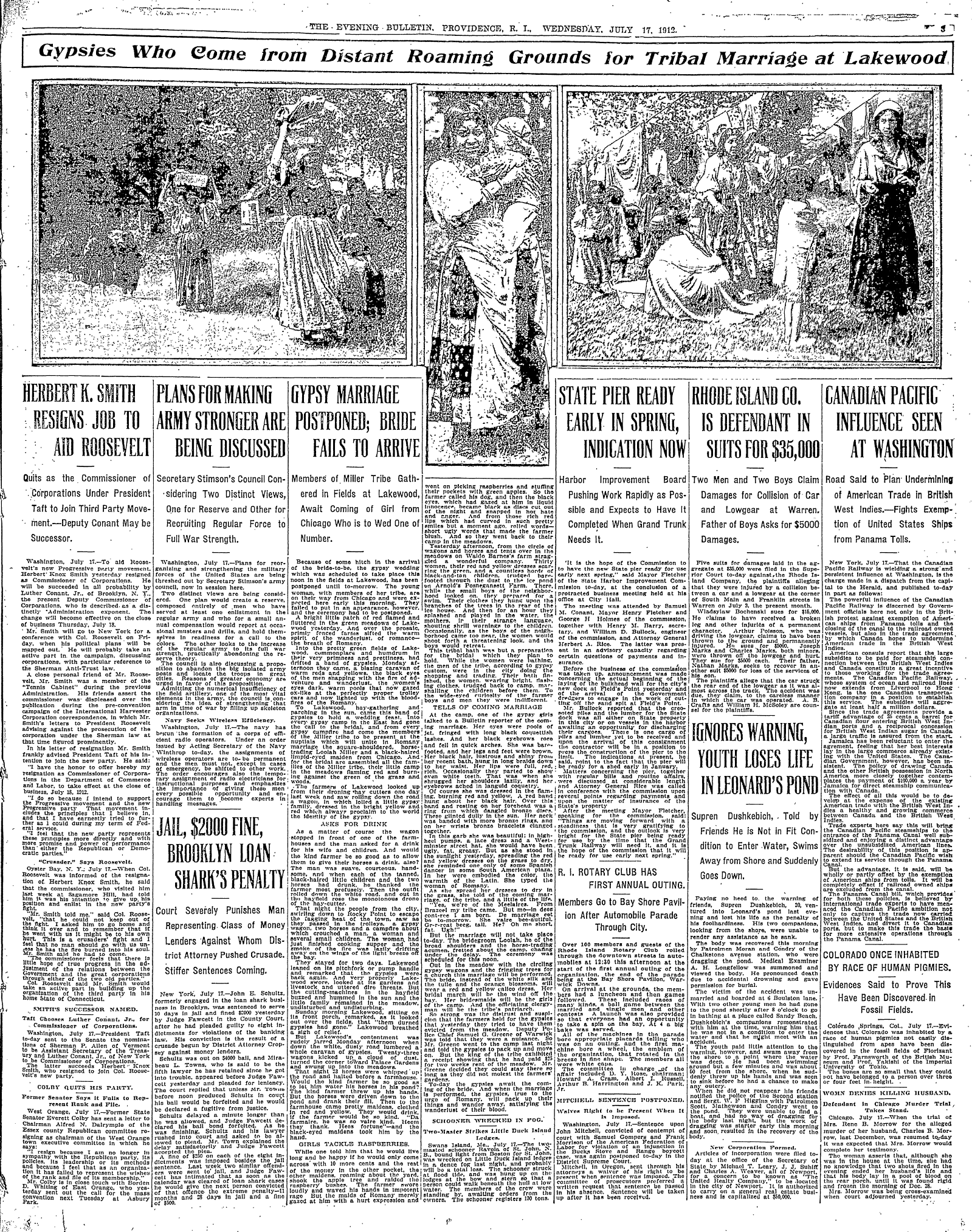

The Evening Bulletin of July 17, 1912, devoted a large part of page 3 to an illustrated report about some Roma, possibly not Romanichals, who had gathered in Warwick for a wedding. The headline read: “Gypsy Marriage Postponed, Bride Fails to Arrive . . . Members of Miller Tribe gather in fields at Lakewood, await coming of girl from Chicago who will wed one of their number.” The bridegroom was identified as “Loolah Miller.” According to the reporter, “Yesterday afternoon, from the circle of wagons and horses and tents over in the meadows on Waldo Barns’s farm straggled a wonderful company. Thirty women, their red and yellow dresses scarring the green, and a countless horde of black and tan children trudged barefoot through the dust to the ice pond on Arnold’s Posnegansett Farm.” The reporter claimed that in the camp, one of the Gypsy girls told him her group was from Brazil. “Her lips were full, red, rich. Occasionally they parted to show even white teeth.” She was “dressed in the flaming, burning red and yellow. A red band hung about her black hair . . . resting on her forehead was a ring from which dangled bronze discs . . . . In this garb she was beautiful; in high heel pumps, a lace dress, and a Westminster Street hat she would have been ugly, fat, greasy.”[11]

This kind of lurid reporting about Gypsies reinforced the idea that they were foreign, strange, and exotic—so unlike regular people that they were not really people at all. One modern scholar, a Romanichal himself, has observed that “the perceived image of the Gypsy has a number of functions in the Euro-American cultural tradition, functions which outweigh the need for a more accurate representation of Gypsies and their history . . . the Gypsy provides a useful body upon which one’s fantasies may be projected.”[12]

This is vividly illustrated by the ubiquity of otherwise benign fundraising events around the turn of the 20th century that relied on Gypsy stereotypes. In November of 1885, the annual fair and festival of the Wickford Baptist Church’s Sewing Society featured a “gypsy tent” where Miss Eva Mathewson and Miss Abby Gardiner, “jauntily dressed in the gypsy style,” told fortunes for a fee.[13] On January 24, 1895, the Helpful Circle of King’s Daughters of the Episcopal church in Auburn put on a “Gypsy Encampment.” Tent-covered booths featured fortune-telling, and the entertainment included a performance of the Gypsy chorus from the opera “The Bohemian Girl.”[14] A benefit for the Roger Williams Eye, Ear and Throat Infirmary featured a gypsy encampment with potted plants surrounding tents that made the venue “look remarkably like the homes of the children of nature. . . . The gypsy-costumed inhabitants added to the realism, from which in turn the articles of luxury and city comfort for sale in the tents somewhat detracted.” Mrs. Mary E. Bliss played the part of the fortune teller.[15] At a Women’s Educational and Industrial Union fundraising carnival in February of 1890, the entertainment included a “gypsy dance” by twenty young men and women dressed in “gay and bizarre costumes,” and a “female minstrel performance” by girls “from a Sunday school somewhere in the Boston area.” The headline above the story in the Evening Bulletin said, “Pretty Girls in Black Face.” The minstrel show apparently elicited some negative comment but the “Gypsy” dance did not.[16]

One of the most painful and unjust stereotypes is the centuries-old myth that Roma kidnap non-Roma children. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, newspapers not only in New England but throughout the United States were filled with child kidnapping stories. Roma were invariably the chief suspects. However, not one newspaper report could be found about an actual Roma

abduction of a child. Most of the stories involved older non-Roma children who ran away from their homes and stayed with the Roma by choice, or custody disputes among Roma families.

A headline on page 8 of the October 24, 1904, edition of the Evening Bulletin read, “Kidnapped Child was Murdered.” The body of a four-year-old boy was found in a deserted farmhouse in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania, with his “throat cut and skull crushed.” Another child told police he had seen the boy kidnapped by a passing band of Gypsies. According to the story, “Five members of one gypsy band headed by Henry Wells have been arrested, but the members of another band who were here on the day the boy disappeared have vanished. Extra police had to guard them to prevent them from being lynched . . . police doubted this band is responsible for the murder” but “hoped they would lead them to the other band.”[17]

In December of 1901, 15-year-old George Ladd of Lawrence, Massachusetts, was discovered living with Romanichals on North Main Street in Providence and caring for their horses. When police approached him, he did not want to leave, but he was taken into custody “for a little lesson in the dignity and force of the law.”[18]

The alleged kidnaping of Leonard Allen, 16, of Middletown, New York, generated headlines in Massachusetts and Rhode Island for months. Police found him in Pawtucket in January of 1907, picking over a waste pile outside the Pawtucket Gas Company. He told them he had been living with a group of Gypsies since the previous summer. Authorities returned him to his mother in New York, but in March of 1908, Fall River police discovered him at the home of Joshua Stanley and charged Stanley and his daughter, Sophia Smith, with kidnapping. The Boston Journal reported that he was found “in a pitable plight, a physical and mental wreck.” As it turned out, Leonard, who was mentally handicapped, told police he had joined the Stanleys because he liked tending horses and living outdoors. Sophia Smith told the police that he had joined the group voluntarily in Allentown, Pennsylvania, and that he had insisted on staying after he was told to leave. Joshua Stanley and his daughter were held on bond and bound over for indictment, but the grand jury found insufficient evidence to charge anyone with kidnapping.[19]

On June 25, 1919, Providence police detained an entire family of seventeen Roma at the Potter Avenue station because of a report from New London police that the family had kidnapped a boy from another Roma family. The detained family explained to the police that the kidnapping story was a scam perpetrated by the brother-in-law of one of the women in their group to obtain money he believed he was owed, and that it had happened many times before, but the police nevertheless held them for many hours until the brother-in-law arrived and acknowledged that the family did not have his son.[20]

Perhaps the most heartbreaking abduction story was that of four-year-old Jimmy Glass of Jersey City, New Jersey, who went missing while vacationing with his family in rural Pennsylvania in May of 1915. A Roma wagon had been seen in the area, and both police and

the boy’s family assumed Gypsies had abducted the boy. For eight years, Roma all over the country were stopped and investigated. On April 15, 1916, a story in the Evening Bulletin had the following headline: “Boy Believed to be Long Missing James Glass Found with Gypsies Here.” Next to the story was a photograph of a dark-looking mother with a light-haired boy. Police believed the boy traveling with a group of Roma in Providence was James Glass, even though he “only spoke a gypsy lingo” and his mother produced a baptism certificate that identified both parents. Finally, in December of 1923, a hunter in Pennsylvania discovered Jimmy’s skull and pieces of his clothing. Evidently, he had wandered away from his parents, became lost, and died of exposure.[21]

Isabel Fonseca, an American who spent four years with Eastern European Roma, has written that “Disinforming inquisitive gadje (non-Gypsies) has a long tradition. It is a serious self-preservation code among Gypsies that their customs, and even particular words, should not be made known to outsiders. It is also a time-honored source of fun.”[22] This may be why obituaries of prominent members of Roma families invariably identified the deceased as the king or queen of the “tribe,” and sometimes even as the king or queen of all of the Gypsies in the United States.

Under the headline “Queen of Romany Gypsy Tribe Dead; Camp in Mourning,” the Evening Bulletin of December 11, 1913, reported that “Mrs. Betsy Bucklin, one of the oldest Romany gypsies in the country, is dead, near Paterson, N.J. In gypsy life in the United States, she was recognized as the pioneer and was considered independently wealthy . . . Queen Betsy was born in Devonshire, England. She came to this country in 1888, when she organized the Bucklin tribe of Romany gypsies. She made nine different trips through every state in the Union.”[23]

Nothing in this obituary was correct except “Queen” Betsey’s date of death and her husband’s first name. Betsey (nee Elizabeth Small) married Plato Buckland in Wayne County, Ohio, on May 15, 1860, so she could not have immigrated in 1888.[24] Plato Buckland emigrated from England in 1857, at the age of 18, with members of the Stanley, Cooper, and Hicks families, so if there was a founder of the “Bucklin (sic) tribe of Romany gypsies” in the United States it probably was him.[25] It is very unlikely that Betsey visited each of the United States nine times. Romanichals were not tourists traveling for enjoyment; they followed established routes.

The Evening Bulletin gave prominent coverage to the 1908 death of Elizabeth Stanley, matriarch of the Rhode Island Stanley family. The headline on page 3 read, “Stanley Tribe’s Former Queen is Dead at 90” and “Once at Head of Gypsey Band, Venerable North End Woman Came to be Beloved and Honored in Community – Native of England.” The obituary said Mrs. Stanley, the mother of well-known horse dealer William Stanley, died at her home on Matilda Street, and that the funeral service would take place on September 15 at North Baptist Chapel. After noting that the Stanley family owned a lucrative horse-trading business and

valuable real estate on North Main and Matilda Streets, the reporter related a story that must have been as entertaining to readers as it was amusing to the members of the Stanley family who told it. “All the sons and daughters of the former queen . . . were educated in the public schools of this city, and have become more or less Americanized,” according to the obituary.

The obituary continued:

“Gradually, one after another, they abandoned the customs peculiar to their tribe and race, gave up the much-colored costumes of their people, and settled down in this city as prosperous, law-abiding citizens. The spirit of Roumania still lived, however, and all the six children but one were married according to the rites of the tribe. When the girls married, their names were adopted by their husbands, to perpetuate the name of Stanley, as is the tribal custom. Only one of the daughters broke away from all the customs and traditions of her people. She had become a thorough American girl, and like many of her American cousins, refused to submit to the long wooing, discarded all the suitors that belonged to her race, and eloped with a young Englishman named Cooper, who had just come to make his home in this country.”

“Only one tribe of gypsies has ever refused to pay homage to Mrs. Stanley, and that is the Hicks tribe of East Providence. It is known as a French gypsy band. The members speak the French language, while Mrs Stanley was born in England, and although of French descent, was recognized as the head of the English-Roumanian tribe of gypsies.”[26]

Two of the Stanley daughters married cousins whose surnames were (already) Stanley. The third daughter married a member of the Cooper family, Romanichals who owned stables in Somerville, Massachusetts. He had emigrated from England with his family in 1851, at about the same time as the Stanleys.[27] The Hicks family also were Romanichals who emigrated from England at about the same time as the Stanleys. There is no evidence that anyone in the Hicks family or the Stanley family spoke French or was “of French descent.”

The obituary further noted that “all the city and police officials who discussed [Mrs. Stanley’s] death this morning spoke of her in terms of praise. Her manner was different from that of the other members of her tribe, and her education much superior.” In fact, like many Romanichals of that era, Mrs. Stanley could neither read nor write, according to the 1900 census.[28] But in a society that equated honesty with literacy and evaluated people based on the color of their clothing, an obituary could not be laudatory unless it described the deceased as educated, law-abiding, and “Americanized.”

The Stanleys and other Romanichals in southern New England did not abandon their Roma identity. They did, however, become highly successful in business. According to anthropologists who studied them, they were the first major Roma group to establish themselves in the United States and the most successful at developing permanent urban locations. Their first stables were established in the Boston area in 1868 and in Providence in 1873, followed by Worcester in 1881, Holyoke, Mass. in 1884, and Fall River in 1893.[29]

The July 17, 1912 edition of the Evening Bulletin has an article and photographs of a gathering for a Roma wedding in Lakewood

It was into this group that Stella Stafford married. On June 6, 1900, Sol is enumerated at what the census taker called the Cypress Street Encampment, located on the East Side of Providence, with his father, five younger sisters and brothers, and another Hicks family.[30] Twelve days later, Sol is enumerated with Stella and their three sons at 395 Park Avenue in Worcester, a two-family house owned by a Hicks relative.[31]

All three of Stella and Sol’s sons became horse dealers. Stella and Sol were divorced by 1902. Her second husband, Messick Smith, with whom she had two children, also was a Romanichal. Eventually they settled permanently in North Carolina. At least three of Stella’s five children married Romanichals. The 1928 city directory for Raleigh, North Carolina, lists Stella as a “palmist.”[32] She died in Raleigh on April 18, 1939.[33]

As automobiles replaced horse-drawn vehicles, the demand for horses declined and selling them was no longer a lucrative business. The Romanichals of southern New England abandoned traveling as a way of life. The Stanley family continued to operate a stable in Providence,[34] and the Hicks family continued to operate a stable in Holyoke, Massachusetts.[35] Others continued to make a living at traditionally Roma trades such as basket-making or metal work, particularly stove and boiler repair.[36] Hicks family members in Holyoke started a sign painting business, and Hicks family members in East Providence were paving contractors.[37] One Stanley family operated an embroidery factory in Guttenberg, New Jersey.[38]

Although an estimated one million Roma live in the United States today, most are, by choice, invisible.[39] Many second-generation and third-generation descendants of the original interrelated southern New England Romanichal families married outside of the family group, but some did not. We may not recognize them, but the descendants of the Romanichals are still here.

Endnotes

[1] Albert T. Sinclair, “American Gypsies” (repr., Bulletin of the New York Public Library, May 1917). See also Brian Vesey-Fitzgerald, Gypsies of Britain (London: Chapman & Hall, Ltd., 1944) and Korad Bercovici, The Story of the Gypsies (New York: Cosmopolitan Book Corp., 1928).[2] R.I. State Archives, Vital Records, Marriages, 1890:392. [3] Ian F. Hancock, “The Origin and Function of the Gypsy Image in Children’s Literature,” The Lion and the Unicorn, Johns Hopkins University Press, 11(1987):47. Hancock is Professor Emeritus of Linguistics at the University of Texas and director of its Romani Archives and Documentation Center. [4] San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, Cal.), April 9, 2015, p. 5. [5] Las Vegas Review-Journal (Las Vegas, Nev.), May 11, 2017, p. 14. [6] “Gypsies in Town,” Evening Bulletin, July 9, 1913, p. 21. Phenix is a village in West Warwick. [7] Evening Bulletin, April 28, 1870, p. 1. How exactly the victim was “soothed into unconsciousness” was not explained. Two Mary Pierces were enumerated in North Providence in the 1870 census, but neither was a widow. [8] Evening Bulletin, Sept. 22, 1884, p. 8. [9] Evening Bulletin, April 14, 1883. p. 8. [10] Evening Bulletin, Feb. 15, 1912, p. 22. [11] Evening Bulletin, July 17, 1912, p. 3. [12] Ian F. Hancock, “The Origin and Function of the Gypsy Image in Children’s Literature,” note 3. [13] Evening Bulletin, Nov. 30, 1885, p. 1. [14] Evening Bulletin, Jan. 25, 1895, p. 9. [15] Evening Bulletin, Dec. 3, 1897, p. 3. [16] Evening Bulletin, Feb. 7, 1890, p. 3. [17] Evening Bulletin, Oct. 24, 1904, p. 8. [18] Evening Bulletin, Dec. 13, 1901, p. 4. [19] Pawtucket Evening Times, Jan. 26, 1907, p. 11; Evening Bulletin, March 19, 1908, p. 21; Boston Journal, March 20, 1908, p. 2; Pawtucket Evening Times, March 26, 1908, p. 8; Evening Bulletin, June 10, 1908, p. 5. [20] Evening Bulletin, June 25, 1919, p. 6. [21] Evening Bulletin, April 15, 1916, p. 3. [22] Isabel Fonseca, Bury Me Standing: The Gypsies and Their Journey (New York: Vintage Departures, 1996), 54.

[23] Evening Bulletin, Dec. 11, 1913, p. 15. [24] Ohio County Marriage Records, 1774-1993, Ancestry.com database. [25] New York, Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists, 1820-1957, Ancestry.com database. [26] Evening Bulletin, Sept. 14, 1908, p. 3. [27] New York, Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists, 1820-1957, Ancestry.com database. [28] 1900 U.S. Census, Providence Ward 2, Providence Co., R.I., roll 1506, p. 7. [29] Matt T. Salo and Sheila Salo, “Romnichel Economic and Social Organization in Urban New England, 1850-1930,” Urban Anthropology, 11(1982):3/4:273. [30] 1900 U.S. Census, Providence Ward 2, Providence Co., R.I., roll 1506, p. 8. [31] 1900 U.S. Census, Worcester Ward 7, Worcester Co., Mass., roll 697, p. 20. [32] Hill’s Raleigh, N.C. City Directory (Richmond, Va.: Hill Directory Co., Inc., 1928), 548. [33] North Carolina Death Certificates, 1909-1976, Ancestry.com database. [34] 1937 Providence Directory (Providence, R.I.: Sampson & Murdock Co., 1937), 933. [35] 1945 Holyoke, South Hadley and Chicopee Mass. Directory (New Haven, Conn.: Price & Lee Co., 1945), 212. [36] Two of Stella’s sons repaired stoves for a living after 1940. (World War II Draft Cards, Young Men, 1940-1947, Ancestry.com database [Joshua Smith]; 1940 U.S. Census, Caroline Co., Maryland, roll 01543, p.14B [Levi M. Hicks].) [37] 1963 East Providence, R.I. City Directory (Boston, Mass.: R. L. Polk & Co., 1963), 199. [38] 1950 U.S. Census, Guttenberg, Hudson Co., N.J., roll 5789, sheet 2. [39] Ian F. Hancock, “Roma.” Texas State Historical Association Handbook of Texas Online (https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/roma-gypsies).