Early accounts of travel in what would become Kent County attest to the wildness of the areas in the colony away from the water, where the economy was centered. While some early farms had developed, much of Kent County held vast tracts of wilderness well into the 18th century.

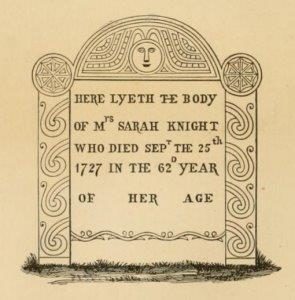

In 1704, a 38-year-old teacher from Boston named Sarah Kemble Knight traversed the Post Road on horse and in carriage from Boston to New Haven and then on to New York. Her account of making her way through Kent County begins with her crossing the Pawtuxet River:

having crossed Providence Ferry, we come to a River wch they Generally Ride thro’. But I dare not venture; so the Post got a Ladd and Cannoo to carry me to tother side, and hee rid thro’ and Led my hors. The Cannoo was very small and shallow, so that when we were in she seem’d redy to take in water, which greatly terrified mee, and caused me to be very circumspect, sitting with my hands fast on each side, my eyes stedy, not daring so much as to lodg my tongue a hair’s breadth more on one side of my mouth then tother, nor so much as think on Lott’s wife, for a wry thought would have oversett our wherey. [1][i]

Having made it safely into Warwick, she found that:

The Rode here was very even and ye day pleasant, it being now near Sunsett. But the Post told mee we had neer ten miles to Ride to the next Stage, (where we were to Lodg.) I askt him of the rest of the Rode, foreseeing wee must travail in the night. Hee told mee there was a bad River we were to Ride thro’, Wch was so very firce a hors could sometimes hardly stem it: But it was but narrow, and wee should soon be over. I cannot express the concern of mind this relation sett me in…

Despite her worries, they reached Hawes Tavern in what is now North Kingstown safely.

In June of 1750, the General Assembly, meeting in Newport, incorporated the towns of East Greenwich, Warwick, West Warwick, and Coventry into ”the county of Kent. [2] Approximately four years later, a journal kept by a young missionary, the Reverend Jacob Bailey, of the travels from his home state of Maine, through the rest of New England, demonstrates the typical scenes and encounters that a traveler of the period would have found. Bailey met up with friend William Brown and his sister “Miss Nabby” in Boston, and decided to accompany them along the Post Road to New London, Connecticut.

They rode through Dedham, Walpole, Wrentham, into Attleboro and Rehoboth in Massachusetts before reaching Providence. The next day, they set out “over a fine plain to Pawtuxet.” Once leaving the small seaside community of Pawtuxet, the three found themselves riding through “a long desert country in which we saw but very few people, and they almost as rough as the trees.” Bailey and his companions had entered Kent County.

They continued through a long stretch of wood, when he wrote that:

we came at length, to a house about the bigness of a hog-sty. The hut abounded in children, who came abroad to stare at us in great swarms, but were clothed only with a piece of cloth about the middle, blacker than the ground on which they trod. Miss Nabby began to wonder that the poor creatures did not wholly abandon themselves to sorrow and despair, but I told her, I made no doubt they enjoyed themselves as much in their savage condition, as she in all her elegance and plenty.

Bailey and his friends continued on, reflecting on the unhappy condition of the inhabitants they had just encountered. With the heat, they soon grew thirsty, and came upon another house,

where we lit, and coming in, found five or six women in a little room without any floor, either over head or under foot. Two or three of them appeared to be young. One of the young wenches made haste to draw us some water, while another made search for a drinking vessel, and the last gave us water in an old broken mug, almost as ancient as time, of which we drank very sparingly.

Setting out once again on their journey, they rode several more miles before arriving at Major Stafford’s inn where:

his daughter came to wait upon us (after absconding for about two minutes) barefooted and barelegged, with a fine patch and a silver knot on her head, with a snuff box in one hand, and a pinch at the nose in the other. She afforded abundance of amusement for my polite companions, which stuck by us longer than anything we met with on our journey. This Stafford’s is in Warwick, about fifty-seven miles from Boston.

The companions traveled on, eventually putting up at Wolcot’s Tavern on the border of what is now East Greenwich, where they were entertained, and served fried chicken with curry sauce, but Bailey recorded that “nothing so much diverted us as had the Major’s daughter.”

Bailey had stopped at the establishment of a singular character of the town. Colonel Joseph Stafford was the great-grandson of Samuel Gorton. A blacksmith by trade, his family had set up the mill at Warwick Neck and built a house there by 1731. Tradition says that the cove had a long reputation from its beginnings as the scene of smuggling goods off boats on Narragansett Bay. Stafford had become a freeman of Warwick in 1718, and was elected multiple times to serve as deputy to the General Assembly for the town. He was a captain in the local militia, and then was promoted to major, and finally to colonel. Stafford was also an astrologer and author of an almanac entitled “Joseph Stafford, Lover of the Truth.” He also served as justice of the peace.

The daughter with whom Bailey had been so smitten was likely Susannah, his youngest child, who would have been thirty-one at the time of Bailey’s meeting her. She would marry another tavern keeper named McGregor.

Visitors coming into Kent County were often unprepared for the wildness of its landscape or the inhabitants who often lived isolated existences. The journal of Samuel Davis, recording a journey through the state along the Old Plainfield Pike in 1773, reported a stop in Scituate as follows:

This part of the colony is thinly inhabited, and the buildings are ordinary. A Baptist meeting-house in Coventry, and another in this place are without glass or doors. There is something savage and wild in the appearance of everything in these back towns. [3]

In the summer of 1780, Claude Blanchard, commissary-in-chief for General Rochambeau’s French army that was stationed at Newport at the time, was touring the state, and in late July decided to visit the wife of Nathanael Greene. In spite of finding the general’s wife “amiable, genteel, and rather pretty,” he was disappointed to find the hospitality in so grand a house wanting:

As there was no bread in her house, some was hastily made; it was of meal and water mixed together; some of which was then toasted at the fire; small slices of it were served up to us. It is not much for a Frenchman. [4]

To be fair, many Rhode Islanders suffered from shortages during the Revolutionary War.

The chaplain of the French commander’s army wrote several letters during his time in Rhode Island, one written in July of 1781 in which he explained the towns inhabited between Providence and Newport:

Scattered about among the forests, the inhabitants have little intercourse with each other, except when they go to church. Their dwelling-houses are spacious, airy, and built of wood, and are at least one story in height, and herein, they keep all their furniture and substance . . . . They all know how to read, and the greatest part of them take the Gazette, printed in their village, which they often dignify with the name of town or city. I do not remember ever to have entered a single house, without seeing a huge family bible, out of which they read on evenings and Sundays to their household . . . . [5]

A French chaplain may be forgiven his surprise at the lack of society in Kent County as he could scarcely understand the daily back-breaking work that was required to maintain the humblest of farms. That he noticed that even rural areas held a high literacy rate, and that Rhode Islanders devoured newspapers and treasured the Bible that held their roots in both religion and genealogy is of note; for those common French people he was acquainted with back home had been under the yoke so long, they were often illiterate and had little inclination to improve themselves with self-education. It must have been an exciting time for the chaplain to witness the American Revolution first hand, and doubtless he brought strong impressions with him on his return to France.

Rural Rhode Island may have seemed a wilderness, but the fierce independence, and vagaries of its people left an ample impression on early travelers to take pen to paper and write of these singular people they had encountered on their journeys.

[Banner Image: Woodcut of a woman on a horse riding in colonial times.]

Notes

[1] Knight, Sarah Kemble, “Journal of…” Miller, Perry (ed.), pp. 12-15 [2] Fuller, Oliver Payson, “The History of Warwick, Rhode Island,” p.97 [3] Kimball, Gertrude Selwyn, “Pictures of Rhode Island in the Past,” p. 106 [4]Ibid. p. 64 [5]Ibid. p. 98