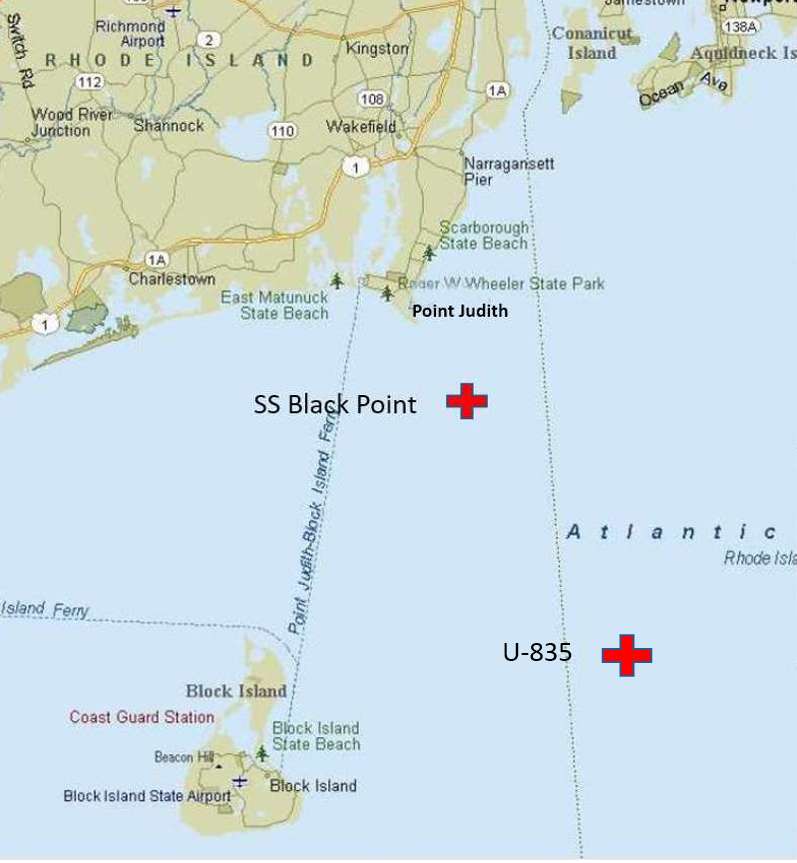

One of the significant stories of World War II emanating from the United States is the sinking of the German U-Boat 853 in Rhode Island waters on May 5, 1945, less than eight miles southeast of Point Judith. It was either the last or second-to-last (probably the latter) German submarine sunk by U.S. forces in World War II, one day before Germany’s official surrender in Europe. It was the German U-boat sunk closest to the U.S. mainland. On May 5 (or possibly the early morning of May 6), all 55 submariners aboard U-853 were entombed in their submerged vessel at the bottom of Rhode Island Sound.

The full story of the sinking of U-853, its sinking of a U.S. coal ship before that, and the sometimes sordid aftermath of the submarine’s sinking, is set forth in a four-part article by Christian McBurney on smallstatebighistory.com (see the links to the four articles at the end of this article) and is also set forth by McBurney in a chapter of a book by smallstatebighistory authors, World War II Rhode Island (see book advertised on the side of this article).

In short, on May 4, 1945, at 5:30 a.m. eastern time, Germany’s navy chief and newly-anointed President of German (Hitler was dead), Admiral Karl Dönitz, by radio ordered all U-boats to cease hostilities. “The war is over.” Either U-853’s tall, 24-year old new commander, Lieutenant Helmut Frömsdorf, did not heed the message or he did not hear it. In the late afternoon of May 5, Frömsdorf torpedoed and sank a coal carrying vessel, S.S. Black Point, less than three miles southeast of Point Judith. Eleven members of the ship’s crew and one guard were killed in the shallow waters off the mouth of Narragansett Bay.

The following day, both U.S. Coast Guard and U.S. Navy ships, using sonar, located U-853. Supplemented with two U.S. Navy blimps from Lakehurst, New Jersey, firing rockets, the U.S. ships pummeled the submarine with tons of depth charges and hedgehogs. U-853 sank and all crewmembers were killed. The vessel and the remains of most of its crew today sits in 125 to 130 feet of water some eight miles southeast of Point Judith.

After the war there was tremendous interest in U-853 among recreational divers, salvage crews, and governments, including the State of Rhode Island, which claimed the sunken vessel.

Grave of the submariner from U-853 buried at the Island Cemetery Annex at Newport in 1960 (V. Karentz)

This article describes my quest to borrow one of U-853’s propellers to display it at a local museum, and the escapades of others who removed (some might say stole) artifacts from and off the sunken hull.

Living in Jamestown, with Castle Hill Lighthouse in my view daily, and as a sailor, I had taken interest in historic lighthouses, including the Beavertail Lighthouse within walking distance of my home. My inquisitiveness turned into membership at Beavertail Lighthouse Museum. I subsequently became a Board Member for the organization dedicated to maintaining the lighthouse and other historic structures at the site and improving the museum’s collection of artifacts.

My curiosity about the Castle Hill Light in Newport led me one day to walk through the brush and foliage above Castle Hill Cove. There two properties are adjoined: land used by U.S. Coast Guard Search and Rescue in Castle Hill Cove, which includes Castle Hill Lighthouse, and land on which the Castle Hill Inn was built in 1875 by marine biologist Alexander Agassiz. My trek from the cove to the lighthouse revealed a surprise—two large propellers. My follow-up inquiry at Castle Hill Inn was met with, “oh, they’re from the German submarine.” A memorial plaque at Point Judith Lighthouse in Narragansett, titled “The Battle of Point Judith,” outlined the story and demise of U-853 for me (Point Judith Lighthouse was then open to the public).

Some years later, I was reminded of U-853’s propellers when I realized that the sinking of the German submarine took place within sight directly south of Beavertail Lighthouse. I thought to myself, our museum docents, with an artifact such as a propeller from U-853 next to them, could make the story of the Battle of Point Judith even more compelling to the museum’s visitors. I decided to inquire further into the propellers.

My research led me back to Castle Hill to reexamine the two propellers. This time the brush had been cleared away and on the hubs of the propellers could be seen stamped serial numbers and markings. I photographed the hub lettering and sent the photographs of them to a Raytheon employee who was a liaison with the German Navy in Bonn. Confirmation came back to me, stating that the propellers were those of U-853 and had been built by the firm of A. G. Weser at the Bremen, Germany, shipyard.

At the time, my son was employed by a law firm in Miami, Florida, Houck Anderson P. A., which specialized in admiralty law. I asked the law firm for an opinion as to the rightful owner of the two propellers. There were a number of different issues to consider, including whether the propellers had been located in international waters or U.S. tidal or territorial waters. Could the propellers be a World War II war prize belonging to the US Navy? Or since they were in Rhode Island waters, did they belong to the State of Rhode Island? What rights did the German government have under international agreements and rules? What rights did a private salvage company or a recreational diver have to an artifact brought up from the sunken submarine to the surface? Was the Abandoned Shipwreck Act of 1987 applicable?

In September of 1953, an entrepreneur of some sort, Oswald Bonifay from Florida and New York, plus a couple of divers, showed up in Newport and hired from Gilbert Brownell a 50-foot fishing dragger named Maureen. Bonifay’s goal was to recover stainless steel tanks filled with mercury and supposedly worth a million dollars, and supposedly used as ballast on U-853. After numerous tries, Bonifay gave up. He cut off the two propellers and the ship’s bell and brought them aboard Maureen. Apparently, some kind of deal was made between Bonifay and J.T. O’Connell, the owner of both Castle Hill Inn and Newport’s J.T. O’Connell Marine Supply store then located on Long Wharf. The propellers ended up in the wooded area between Castle Hill Inn and Castle Hill Lighthouse. They remained there for the next 52 years. The location of the ship’s bell is unknown.

I followed up on the propellers in June 2005 with Timothy O’Reilly, the manager of Castle Hill Inn and the Newport Harbor Corporation. He informed me that the two propellers had belonged to his grandfather, J. T. O’Connell. I responded that according to the admiralty law firm’s advice I had received, the propellers were most likely under applicable law considered to have been stolen, regardless of the deal struck between his grandfather and Bonifay. Within a week I received a letter from Castle Hill Inn stating that the two propellers were to be donated to the Newport Historical Society.

Surprisingly, that transaction never occurred. Rather, the propellers ended up with Newport’s U.S. Naval War College Museum. I again asked for the loan of one of the propellers for Beavertail Lighthouse Museum. In December 2006, I received the following response from noted maritime historian John Hattendorf on behalf of the U.S. Naval War College Museum:

In regard to the U-853 propellers, I must tell you that they are not available for loan. The transfer of ownership for the propellers was a complicated procedure. In November 2004, the German Ambassador to the United States wrote to the Secretary of the Navy and declared the German government’s ownership of the propellers, stating that “Because U-853 was never captured and did not surrender, the German government has clear title to these propellers in accordance with international law.” In this letter the ambassador presented the propellers as “a gift to the United States Navy and to the American people” with the request that they be “exhibited at the U.S. Naval War College Museum in Newport, Rhode Island, to provide better public access and to help interpret the history of U-853 and its crew as part of the unique naval history of Narragansett Bay.” As you mentioned, the propellers were for many years located at the Inn at Castle Hill. In subsequent discussions, Mr. O’Reilly and his family very generously relinquished all claim to them in favor of the U.S. Naval War College Museum. And the Newport Historical Society, which at one time had a plan to display them, also relinquished its interest in the propellers. The Naval War College Museum presently has the propellers in storage and does intend to display them in the future in a way that will appropriately meet the German government’s request. We are currently working on plans for this, but no final decision has yet been made when this will take place. I hope that it will not be long before we can have them available on display here.

With very best wishes for the New Year,

Yours very sincerely,

John B. HATTENDORF, D.Phil., L.H.D., F.R.Hist. S.

Ernest J. King Professor of Maritime History,

Chairman, Maritime History Department, and

Director, Naval War College Museum

For years the propellers were exhibited at the Island Cemetery Annex, where many Navy and allied sailors are buried (and one submariner from U-853. Eventually, the Naval War College established a fine outdoor display of the propellers on the grounds of the War College, including a marker covering the sinking of U-853.

The two propellers and the ship’s bell were not the only apparently unlawful removal of artifacts from the sunken submarine. Sometime in the 1960s, divers removed the upper part of U-853’s periscope.

In 1960 a group from Trumbull, Connecticut, organized by Burton Mason of a firm called Submarine Research Associates, made efforts to salvage the submarine. Its divers entered U-853 a number of times, removing articles as souvenirs, including the upper portion of one of the submarine’s periscopes. Mason boasted that he was going to raise the entire vessel. His most notable exploit was the removal of a single unknown crewmember’s skeleton. Shortly thereafter, these remains were buried in Newport’s Island Cemetery Annex with military honors and an entourage from the German consulate in attendance. (The German consulate then requested that the remains of other submariners lay undisturbed where they are today.)

In May 2006, a story was written about the Gyro Navigation Compass belonging to U-853 being removed under the guise of archaeological exploration and the Abandoned Shipwreck Act of 1987, U.S. Code 43 Section 2. A former firefighter, Earl King of Norton, Massachusetts, along with a dive partner, in July1973 had apparently cut loose the compass from U-853 and had had it appraised. The appraiser reportedly told King that King had hit the jackpot and the item was worth tens of thousands of dollars. King, in turn, wrote to the German embassy to see if it would bid on this “golden compass.” The disposition and current whereabouts of the compass are unknown.

One of the more interesting objects removed from the U-853 was one of its navigation sextants. This came to light when the noted marine instrument company Robert E. White Inc. of Boston in 2007 advertised on EBAY that the C. Plath, Hamburg, Germany’s (Kreigsmarine) sextant was up for auction. Complete with engravings and ID numbers tracing the sextant back to the German Navy and U-853 itself, it was listed as a “once in a lifetime opportunity to own an exceptionally rare World War II artifact.”

The advertisment for the auction attempted to trace the lineage of the sextant, presumably in an effort to establish that it came from U-853, which would make it more valuable than another German U-boat. It stated: “The sextant’s owner’s late husband was a member for many years of a small yacht club, the Ishoda Yacht Club, the 4th oldest in the U.S., in South Norwalk, Connecticut. He had some friends who, in addition to being active boaters, were accomplished scuba divers. They told him that they had dived on the wreck of a U-boat off Block Island and had recovered this sextant, evidently from an air pocket inside. The wood case and the sextant itself show some deterioration from moisture, but not it seems from immersion. The sextant was presented as a gesture of friendship, and it lay in storage for many years in the house of the recipient. On the death of the owner, his widow inspected a number of his effects and came across this instrument, which she recalled from years earlier.” Robert E. White Inc. estimated the value of the sextant at $5,000.

Another significant artifact removed from the sunken U-853 was one of the two 20 mm Flak38 AA guns mounted firmly on U-853’s deck. This fascinating story began with a report in August 1968 that the German Embassy in Washington, D.C. had entered into an agreement with an American firm to salvage U-853. The German government may have been inspired by (false) reports that the submarine contained a horde of gold. The Coast Guard later gave the name of a New York salvage company as the contractor, The Murphy Machine Salvage Company, with M. L. Recovery Corp. of Georgetown, Delaware as the subcontractor. In October and November of 1968 a salvage team hired by Melvin Joseph of Georgetown, Delaware, was prepared to raise the entire submarine.

U-853’s 37mm deck gun restored and on display at the Fort Miles Historical Association’s museum at Lewes, Delaware

Remarkably, the Philadelphia Inquirer, in its November 16, 1968 edition, published a report that U-853 had been raised Melvin Joseph Company and that the submarine was being towed to Lewes, Delaware. The German Consul in Boston had also informed newspapers that the submarine had been lifted by Melvin Joseph Company and was being towed to Delaware. The Associated Press released the story and more than twenty newspapers ran the story. All of the rumors and claims were untrue. First, bad weather hampered the effort. Then Submarine Research Associates of East Greenwich sent a telegram to the Coast Guard stating, “Submarine contains explosives unsafe to be brought into port.” It appears that because U-853 was still surrounded by unexploded hedgehogs and depth charges, the scheme for raising the submarine was dropped.

Melvin Joseph was interviewed at the time, but gave little information. One newspaper report described him as being as closed-mouthed “as a Chincoteague oyster.” Joseph, however, kept U-853 in mind.

I was informed about the following salvage attempt by Joseph. In 1981, a 100-foot wooden salvage tugboat from a Maryland group, again hired by Joseph, apparently looking for treasure that reportedly was on board the submarine (the story was still untrue) hovered over the sunken submarine. The tugboat’s divers unwisely anchored the tug to one of the submarine’s gun mounts. A storm arose ripping away the gun from the hull. The tugboat’s crew took the gun aboard the tug and the apparently deposited the gun somewhere in New Jersey, possibly Cape May. Joseph moved the gun to Delaware where he sometimes mounted it on the back of his pick-up truck to show off to his friends or displayed it in front of Joseph’s business location at Georgetown. The letter writer informed me that the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) intervened, declaring that it was an unlawful weapon. In the 1970s, Joseph then donated the weapon to Delaware Technical Community College, located at Dover, Delaware. The college, not knowing what to do with it, placed the gun in its outdoor maintenance yard. In 2004 the well-travelled gun was fortunately rediscovered and rescued by Dr. Gary D. Wray of the Fort Miles Historical Association, which operates a World War II Coastal Defense site at Cape Henlopen State Park in Delaware. The 20 mm deck gun was refurbished and is currently displayed in the association’s museum at Lewes, Delaware.

What happened to the second 20 mm deck gun is not known. It could be that it was blown off by the explosions by the many the depth charges and hedgehogs fired at U-853 on May 5, 1945.

U-853, after spending the last 75 years underwater, has been visited by many recreational divers. The count is unknown. Although murky waters limit visibility, it remains a popular dive site. The hull has deteriorated and continues to disintegrate. How many divers have entered the submarine and taken souvenirs is also unknown. The remains of 53 German sailors are scattered within or around the tomb (one dead submariner was brought the surface shortly after the sinking and where those remains are now is unknown; another submariner’s remains were brought to the surface and buried in 1960, as explained above).

Christian McBurney, after reviewing my article, told me a story of a discovery he made of where a remarkable artifact from U-853 is located. He wrote about it at the end of the last of his four-part article on U-853:

I visited USS Slater, DE 766, one of the last destroyer escorts that survives from World War II. Destroyer escorts proved to be a vital weapon in the successful war against German submarines. Slater, a sister ship to Atherton that received partial credit for sinking U-853, is moored on the Hudson River in Albany, New York. It is worth visiting, including seeing its collection of depth charges and hedgehogs, seemingly ready for action. It is part of the Destroyer Escort Museum. I had to remind the museum’s curator that it also possess the officer’s cap that belonged to Lieutenant Helmut Frömsdorf and other debris that floated up to the surface and was recovered during the attacks, thanks to a donation by Atherton’s former commander, Lewis Iselin. Perhaps these items can someday be returned to, and displayed in, Rhode Island.

No doubt the saga of U-853 will continue for years to come.

Sources:

Christian McBurney, all on smallstatebighistory.com:

The 75th Anniversary of the Battle of Point Judith: German U-Boat Sinks U.S. Coal Vessel http://smallstatebighistory.com/the-75th-anniversary-of-the-battle-of-point-judith-german-u-boat-sinks-u-s-coal-vessel/

The 75th Anniversary of the Battle of Point Judith: Could U-853’s Sinking of Black Point Been Averted? http://smallstatebighistory.com/the-75th-anniversary-of-the-battle-of-point-judith-could-u-853s-sinking-of-black-point-been-averted/

The 75th Anniversary of the Battle of Point Judith: U.S. Navy and Coast Guard Warships Sink U-853 http://smallstatebighistory.com/the-75th-anniversary-of-the-battle-of-point-judith-u-s-navy-and-coast-guard-warships-sink-u-853/

The 75th Anniversary of the Battle of Point Judith: The Fate of U-853 After Its Sinking; Bodies-And Bones—Are Removed; What Happened to Hoffman’s Body? http://smallstatebighistory.com/the-75th-anniversary-of-the-battle-of-point-judith-the-fate-of-u-853-after-its-sinking-bodies-and-bones-are-removed-what-happened-to-hoffmans-body/

Christian McBurney, “The Battle of Point Judith and the Sinkings of Black Point and U-853,” in Christian McBurney, et al., World War II Rhode Island (History Press, 2017).

“Delaware Firm Raises U-Boat; Fortune Denied,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Nov. 19, 1968.

DiCarpio, Ralph. “The Battle of Point Judith.” Destroyer Escort Sailors Association. http://www.desausa.org/Stories/battle_of_point_judith_2.htm.

Cyber Diver News Network (CDNN), May 26, 2006

Delaware History Group, Letter from Joseph Kosaveach to the Author, June 1, 2017.

“Fort Miles Seeks World War II Artifacts,” Cape Gazette, Aug. 29, 2014 and The Daily Times (Salisbury, Maryland), Aug. 31, 2014, pp. 59 and 61 (the articles, which include different photographs of the modern display of the 20 mm gun, can be accessed online at http://cpg.stparchive.com/Archive/CPG/CPG08292014p079.php and https://www.newspapers.com/image/111876157)

Franks, Bill. Wilmington Morning News, November 23, 1968.

Gabriel Leiner, Boston Herald, May 26, 2006.

Lynch, Adam, “Kill and Be Killed? The U-853 Mystery,” Naval History Magazine 22, no. 3 (June 2008).

Naval War College, Letter from John Hattendorf to the Author, Dec. 28, 2006.

Newport Daily News, Oct. 25, 1960, and Jan. 17, Jan. 21, Jan. 31, Feb. 23, and May 2, 1961 (dealing with proposal to raise the wreck of U-853 and burial of remains of crewmembers).

Palmer, Captain Bill, The Last Battle of the Atlantic: The Sinking of the U-853 (Wallingford, CT: Thunderfish Video and Publications, 2012).

Providence Journal, Feb. 23, 1961.

“Salvagers Raise Sub, Start Tow,” Bridgeport Post, Nov. 19, 1968 (Associated Press story).

The History Detectives, Episode12, 2004 (television show)

“U-boat’s Whereabouts Still Shrouded in Mystery,” The Morning News(Wilmington, Delaware), Nov. 20, 1968.

“U.S. Firm to Salvage U-Boat 853,” Miami News, Aug. 21, 1968 (Associated Press report).