[This article commemorates the 75th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor, and will appear as Chapter 1 in an upcoming book by five smallstatebighistory authors titled World War II Rhode Island, which is scheduled to be released by History Press in Spring 2017]

Rhode Island already had a sizeable military and defense industry presence before the country’s entry into World War II. Knowing that the nation could become embroiled in either or both of the wars in Europe and Asia that started in the late 1930s, the country and the state began to ramp up their military production and preparations. These activities made Rhode Island’s residents worried that their state could be targeted for attack by enemy forces.

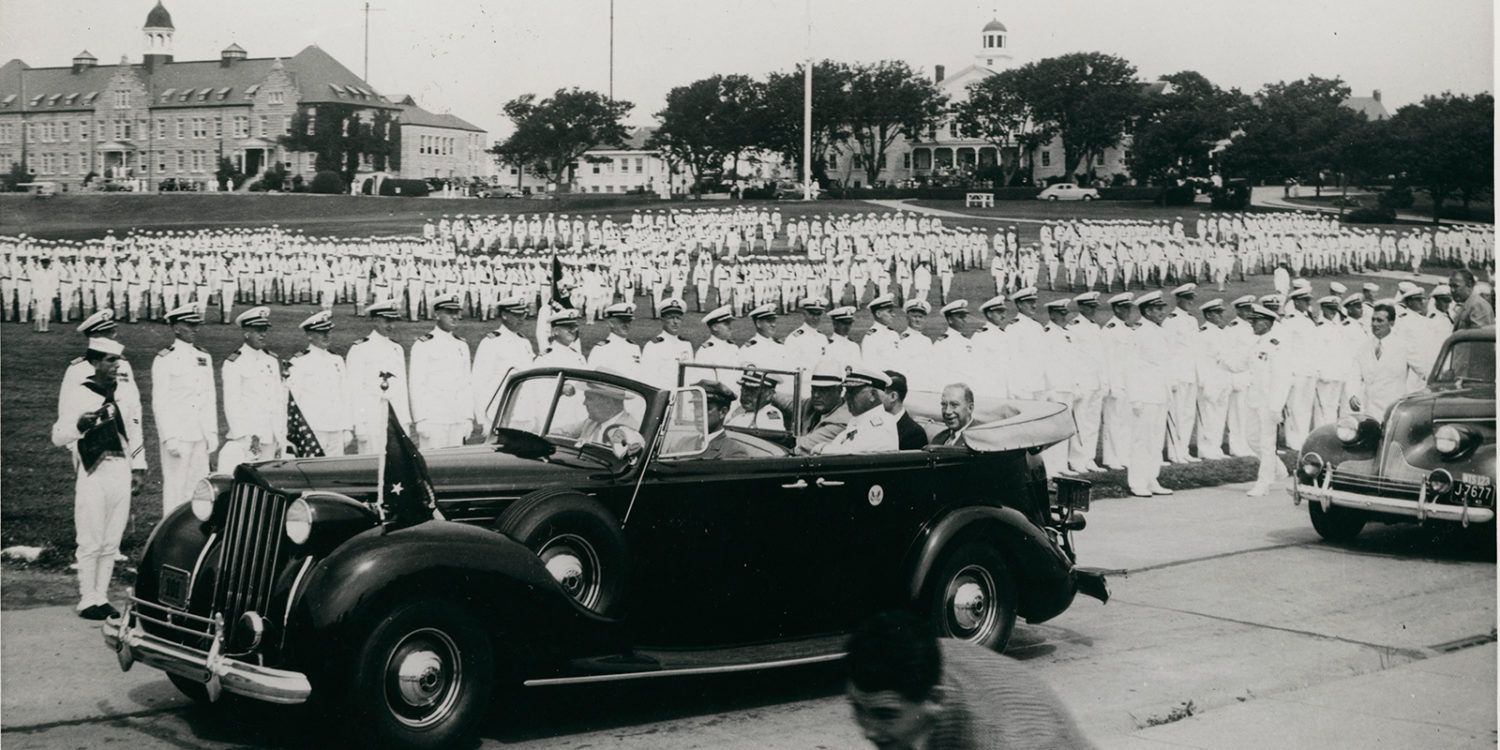

Still, Rhode Islanders were thrilled when on August 12, 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt arrived in Narragansett Bay on board the presidential yacht USS Potomac to see the navy’s expanding military facilities. The president quickly inspected the naval torpedo station facilities on Goat Island, peering through torpedo factory windows and viewing a completed torpedo. Thousands cheered him on Long Wharf. After reviewing 2,100 new naval recruits at the naval training station on Coasters Harbor Island, the president then took his yacht under the recently opened Jamestown Bridge, with workboats following and sounding their whistles, in order to observe in the distance construction efforts at the new naval air station at Quonset Point. Less than three hours after arriving at Newport, Roosevelt began his trip out of Narragansett Bay.

President Roosevelt, in the front passenger seat, reviews cadets on the grounds of the Naval Training Center at Newport (now the grounds of the Naval War College) on August 12, 1940, with Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox , Senator Theodore F. Green and Admiral Edward C. Kalbfus (FDR Library and Naval War College Museum)

With tensions rising between Japan and the United States, it was not a complete surprise when news of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor swept over the radio airwaves on December 7, 1941. Still, it was a shock. Helen Clarke Grimes, listening to her wooden radio in Providence, wrote in her diary, “I guess this is it! Japanese dive bombers have attacked Honolulu!”

In Providence, seventeen-year-old Jack DiPretoro, who had worked with thousands of other Rhode Islanders to construct the naval air station at Quonset Point earlier in the year, thought about that sign he saw at the North Kingstown naval facility, asking for civilian volunteers to work at the navy base at Pearl Harbor. He wondered if any workers accepted the offer and, if they did, whether they survived December 7. (DiPretoro, after becoming an experienced combat fighter pilot in the Pacific, in April 1945 returned to fly TBF/TBM Avenger aircraft in Narragansett Bay, with his crew practicing torpedo launches.)

The Pearl Harbor attack understandably created a climate of fear about the security of the country and state. This concern quickly morphed into fears of spies and saboteurs and recent immigrants who could be secret enemies.

The December 8, 1941 Providence Journal reported that the secretary of war’s call for “increased precautions against sabotage in defense plants met [with] almost instantaneous compliance” in the state. “Rhode Island intensified its precautions against sabotage with swift action last night,” the newspaper trumpeted, “to protect its sprawling defense workshops, key utility and transportation facilities serving them, and the waterfront where the materials of war are setting out on world-wide journeys.”

The December 8 newspaper further reported on a five-hour meeting called by the state’s governor, J. Howard McGrath, a Democrat from Woonsocket in his first of three wartime terms as governor. McGrath and the executive committee of the State Council of Defense took steps to mobilize the “State Guard to protect public property.” After this meeting, according to the newspaper, “Guards took up posts at the State Airport and extra patrols were assigned to waterfront points and reservoirs,” and state police “set up an all-night anti-sabotage guard.”

McGrath and the State Council of Defense further mandated the “immediate registration of all alien Japanese in Rhode Island.” Those who failed to register would be “subject to detention.” The governor also called on “employers and citizens who know of Japanese residents” to inform the police. In its December 9 edition, the Providence Journal reported that the “round-up of German and Italian aliens” in the state “believed to be dangerous to the safety of the nation” would be carried out by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), even though Hitler would not declare war of on the United States until December 11. The next day, Providence’s FBI office reported rounding up four Germans as enemy aliens.

The Providence Journal further reported that during the evening of December 7, “several extra buses rolled up to the [bus] station at Fountain Street, to carry sailors and marines back to Newport naval establishments and soldiers to Fort Adams. These extra buses to Newport were kept in service until after midnight, and other special buses were placed in service to take men to Quonset and the Jamestown forts.” The New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad—running trains out of Grand Central Station in New York City—added “special trains bringing hundreds of sailors on leave from Newport back from New York to Providence.” The sailors would then have to make their way by bus to Newport.

With the surprise attack at Hawaii, concern arose about the possibility of Germany and Italy attempting their own surprise attack against the United States on the Eastern Seaboard. Military leaders remembered German saboteurs during World War I blowing up a massive munitions depot in New York Harbor on Black Tom Island, which had exploded with the force equivalent to an earthquake measuring 5.5 on the Richter scale.

Thus, the stage was set for December 9, when at 12:45 p.m. an air raid alert was issued to military bases warning that “enemy planes” were “reported one hour from New York.” Panic spread in the state. In Newport, the information was that German bombers were only a short distance away. How this was possible, when Germany had no aircraft carriers to launch bombers, was not explained. In any event, Newport’s schoolchildren were sent home, off-duty policemen and firemen were called in and an emergency plan was put into effect. Off Newport, moored at buoy 7, the flagship of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet, the heavy cruiser USS Augusta, prepared for an attack.

An unnamed newspaper reporter’s telephone call to the naval air station at Quonset Point about the alarm prompted an air raid alert to be sounded, leading to the evacuation of the 784 civilians employed at the Quonset Point facility, as well as 1,500 workers from nearby Davisville. The station’s 3,740 officers and enlisted men readied themselves for an air raid.

Governor McGrath ordered the highways cleared and called out the state National Guard. Schools were dismissed in most towns and stayed closed for several days. 004

Within two hours, military authorities realized the alarm was a false one and issued the “all secure” signal at 2:46 p.m. The next day, the Providence Journal reported that an “erroneous alarm” from Mitchell Field on Long Island of the sighting of enemy planes off the East Coast had set off a series of air raid alerts in a wide area. In fact, the planes turned out to be U.S. Navy PBY Catalinas flying from Newfoundland, Canada, bound for Quonset Point.

Planes and other equipment at the Naval Air Station at Quonset Point are dispersed in case of a surprise enemy attack, on December 9, 1941, taking a lesson from the attack on Pearl Harbor (Naval History and Heritage Command)

Germany and Italy finally declared war on the United States on December 11. That day, Rear Admiral Edward C. Kalbfus, the chief of all U.S. Navy operations in Rhode Island, and General Ralph E. Haines, commander of the U.S. Army’s Harbor Defenses of Narragansett Bay, met to discuss how to guard against a surprise attack by Germany and sabotage by enemy sympathizers. According to the Newport Mercury, “Heavy guards were posted at all vital spots in the bay area and gun and searchlight crews have taken up their positions.” “Soldiers were swarming in from leave and furloughs,” the newspaper added, noting that many had to cut short their holiday leaves.

Block Island, a small island thirteen miles south of the coast of the Rhode Island mainland, as was the case with all United States wars with European powers starting with the American Revolutionary War, was particularly exposed. It was also a useful place for U.S. military forces to maintain lookouts for the enemy. As early as December 8, 1941, William Doggett, the owner of a stone house perched on top of Beacon Hill, the highest point of Block Island, was informed by an army officer that his property had been seized for use by the army for the duration of the war. It was one of the first of many Rhode Island coastal homes that would be commandeered by the army or navy during the war years.

Block Islanders, at least, were not intimidated, despite residing on one of the most exposed islands on the country’s Eastern Seaboard. On January 28, 1942, members of the State Council of Defense took a boat to the island to meet with local island leaders at the National Hotel. Warning of a possible German invasion and attempt to use the island as a “bridgehead” for an attack on the mainland, the state officials offered to evacuate all 671 islanders to the mainland. None of the locals showed any interest in the proposal. “There ain’t a thing here any enemy would wantta get a hold of, so fur as I can see,” said George Sheffield, the head of the island’s civilian defense efforts. When alerted to the possibility of food shortages on a stranded island, Joseph Pennington retorted, “You can’t dig clams in Westminster Street and you can’t get lobsters in Scituate.” The state’s press admired the islander’s spunk, and the Rhode Island House of Representatives passed a resolution congratulating Block Islanders for their “patriotic fortitude.” Representative Erich A. O’D. Taylor of Newport commented, “At last some people have been found in Rhode Island who are not afraid—a spirit I would like to see more generally distributed through the state.” Meanwhile, coast guard personnel patrolled the seventeen miles of beaches and army soldiers manned tall cement lookout towers on Block Island, as well as at key points on the state’s southern coast, searching for enemy planes, ships and submarines.

Rhode Island was declared a “vital war zone,” which meant strict security against spies and precautions against sabotage of military bases and war industries. Posters at defense workplaces warned, “Loose Lips Sink Ships.” When seventeen-year-old Elisabeth Sheldon of Saunderstown obtained a permit to sail her fifteen-foot sailboat in parts of Narragansett Bay, her permit included this ominous condition: “ENEMY ALIENS ARE PROHIBITED ON BOARD.”

In fact, there were only a very few supporters of Germany in Rhode Island. One was Nicholas Hansen, who was born in Newport of German parents and worked at the highly sensitive torpedo station in Newport. He admitted to the FBI that he was an admirer of Hitler, that he would “much rather fight for Hitler than the United States” and that he would be willing to participate in a plot to blow up the torpedo station. He conceded, however, at his court hearing in Providence in July 1942, that he was not intelligent enough to carry out such a plot on his own—his lack of intelligence was indicated by his unusual admissions.

In another case of suspected sabotage, on October 26, 1943, Henry Strunz—reportedly of German extraction—was arrested by the FBI after being accused of impeding production at the Walsh-Kaiser Shipyard in Providence. He was said to have stuck cigarettes in the nozzles of acetylene torches, loosened valves on acetylene gas tanks and conducted other acts to hinder the war effort.

As early as 1939, a Joseph Demurs, a civilian employee at the torpedo station in Newport from West Warwick, had been charged with sabotage. He was accused of mixing acid with lubricant oil in the torpedoes’ propeller mechanism, “making it a dud.”

Virtually all Rhode Islanders, including the few German Americans and the many Italian Americans, were fiercely loyal to the United States. Perhaps a majority of Rhode Islanders crowded around their radios to hear President Roosevelt’s “Day of Infamy” speech. They were stirred by his clarion call, “With confidence in our armed forces—with the unbounding determination of our people—we will gain the inevitable triumph.”

In the days after Pearl Harbor, thousands of Rhode Island young men flocked to enlistment centers to join the army, navy, air force or coast guard. College-age men on campuses in Providence and Kingston suddenly became a rare sight. Employees at the many defense plants in the state mentally prepared to work harder than ever before. Everyone thought about how they could contribute to the war effort. Women who had not before worked outside the home wondered if they would be called on. It was an exciting time. Rhode Islanders had another feeling too—anxiety, for not knowing what lay in the future for themselves or their families and friends, state and country.

[Banner Image: President Roosevelt, in the front passenger seat, reviews cadets on the grounds of the Naval Training Center at Newport (now the grounds of the Naval War College) on August 12, 1940, with Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox , Senator Theodore F. Green and Admiral Edward C. Kalbfus (FDR Library and Naval War College Museum)]Bibliography

Boston Globe, July 2, 1942, and Oct. 27, 1943.

Cincinnati Enquirer, July 2, 1942.

DiPretoro, Jack. Interview by Christian McBurney, June 14, 2016.

Downie, Robert. Block Island—The Land. Block Island, RI: Book Nook Press, 2001.

Lancaster, Jane, ed. “‘I Go onto Detail Mostly on Account of Posterity’: Extracts from the World War II Diary of Helen Clarke Grimes,” Rhode Island History 63, no. 1 (Winter/Spring 2005): 3-24.

Morgan, Thomas J. “President Roosevelt Visits Newport,” Providence Journal, August 12, 1990.

Newport Mercury, Dec. 12, 1941, and July 3, 1942.

Providence Journal, Dec. 8-10, 1941.