After scouring the coast of New England, my father found a shingled dwelling in Saunderstown, Rhode Island, perched high above the rocks on the west bank of Narragansett Bay. It wasn’t a surprising choice; for decades his parents had summered by the bay. It was 1929 and our family—my two parents, four siblings, and I—moved in for the summer.

Our rambling house overlooking the water had been built by a Louisiana man forty years before of flexible and weathered cypress that was able to withstand the continuous battering of sea and wind. During storms the old house would adapt to the fury, swaying with the gale, giving of itself rather than shuddering and cracking as lesser houses did.

My father’s parents had often spent their summers at the old Saunders House at the ferry landing down the road, taking the train up from their home in Savannah, Georgia. Dad liked to tell us how, as a boy, he roamed over the waters during the benign summer months. He would row half a mile across to Conanicut Island, then haul his skiff over the isthmus farther on that separated chunky Beavertail from what must have been imagined as the rest of a beaver’s body to the north. Leaving the island, he would plunge on toward Newport where he could scoot the skiff up under the sterns of many-masted schooners resting at anchor or moored along the wharves after long expeditions to other lands. Along the way he explored every inlet and cove until he knew them all.

Our father was a man of the sea. When he was not actually out on the waters, he was thinking and reading about the sea or preparing to go out on the sea. When a squall was brewing, he would bring me out on the sheltered porch and we would watch dark clouds form up the bay, turning mauve, then black, while the sea below churned to a dark indigo with white caps leaping like white fire over the waves. This riotous blackness would move slowly, gobbling up the blue-gray calm to where we waited by windless water until the fury hit us with the force of its blast.

“You’re lucky that you’re not out there now!” My father would chuckle, wrapping his huge bear’s arms around me protectively, enabling me to bear witness to the raging furor. He came naturally by his love of the sea; it flowed in his Rhode Island blood, for his grandfather and great grandfathers had been sea captains and whalers who sailed out of Providence.

James Rhodes Sheldon operating Skidaway, a former rum runner from Prohibition times that plied Narragansett Bay, circa 1938 (Elisabeth Sheldon Aschman Collection)

Dad was a large man, his arm muscles well developed by rowing skulls, alone and with teammates at Yale. Hadn’t they won the legendary race against Harvard in 1915? But the pedestrian life of a businessman had slowed his physical activity. The slim-waisted figure who once strode the beach in Narragansett, catching the eyes of New York socialites decked out in the long bloomers of the day, had expanded. Now his huge frame was well-padded. Hair had slipped from the top of his head, which looked more like the sun that rose over Dutch Island across the bay than the well-modeled noggin his young wife had once gazed on. But even now he remained strong. He could carry a skiff to the water single-handed, and he could haul in a main sheet, billowing with half a ton of air, not needing the aid of modern coffee-grinder winches. His five children stood in awe of him. None of them would dream of challenging a command from their captain on board ship or, in fact, on dry land.

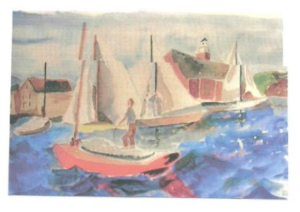

Our father insisted that all of us children learn to sail and, even more, to race. All summer long Dad’s progeny underwent training, so that when we raced against other boats, we would automatically make the right moves, losing no time. He composed sets of rules typed on small yellow pages and bound in booklets for each of his children, each a different and distinct member of the crew. As the fifth child, at age seven, I was designated Chief Ballast, while the ship was underway and Chief Bailer when we were in port. This meant that I had to learn to position myself in a certain part of the boat where my meager weight might be needed as we tacked into the wind or scudded before it. My arms weren’t strong enough to be much of a bailer, but I would flail at bilge water with my cup.

Louise sailing her family’s Lawley 15 sailboat in Wickford Harbor. Watercolor by Louise Sheldon MacDonald, 1988.

My older siblings, Rhodey and Peggy, had more important roles to learn like Helmsman and Chief Mate, while Irving and Betty served as jib-tenders. Dad taught us to think that each job was vital to the ship’s successful maneuvering. We learned how to hold the tiller loosely in our fingers so that they would be sensitive to the pull of wind and water. We learned to balance the boat under all conditions, evaluate the wind direction and velocity, check the movement of the tide, and above all, keep the boat moving, whether it was sailing close-hauled on a tack, at mid-point on a reach, or loosely with the sail out over the water before the wind. We learned how to care for the boat, haul it from the water, scrape it, paint the bottom and sides. We learned to set the rigging. Of course, everyone qualified as a bottom scrubber. On racing days we plunged overboard with sponges and brushes to guarantee the smoothest, fastest hull in the fleet.

Daddy helped all five of us learn the intricacies of racing. When I was thirteen, he announced that I was ready for skippering. In a fifteen-foot Lawley, a sailboat that he had introduced to Saunderstown, we raced in a two-day regatta off Newport. Slouched down in the cockpit, Dad handled the jib and mainsail, while I was on the tiller, thrilled to be in control. Like a filly coursing over the race track, the trim Sirocco slipped gleefully through the waves as though her heart were pounding as hard as mine. The breeze was perfect, a moderate southerly. Every minute Dad was softly advising: “keep her up to the wind,” “we’re overtaking; stay on your course,” and “time to tack, cover that other boat.” My throat ran dry as, miraculously, we gained an inch and then another. It seemed I didn’t have to do anything, just listen to Daddy’s whisper and move the tiller ever so gently, as he guided me.. When we moved ahead of the fleet, Dad’s puckish face lighted up, breaking into that all-out grin and he murmured softly, so as not to slow the boat, “Life is a bowl of cherries!” That was his favorite line when things were going well. We came in first and second in the two races. Later, with Betty or Irving I experienced the thrill of racing as a crew member, but I never savored a race as much as those with Daddy.

When Dad organized a Sunday outing of our small fleet to Prudence Island, no one was left behind. Mother, the gracious socialite, fulfilled her role as well as we did. She, who had skippered in ladies races, now created watery scrambled eggs on our motor launch and made sure that all her children., as well as her guests, were well-fed, happy and occupied. The launch Skidaway had served lawless years during Prohibition as a rum-runner, bringing illegal alcohol up the rivers and into secret coves. Built low on the horizon to escape detection, she now made a perfect tender for sailboats.

Our father believed that sailing is training for every important activity in life. We learned to work as a team, to react swiftly, to bear the cold, when shivery and wet, and never to complain. On one expedition aboard Skidaway to view the famed America’s Cup races off Newport, I clambered into the fore cockpit with a friend, firmly intending to prove my superior experience as a seafarer. As Skidaway knifed forth at full speed through a choppy sea, we reveled in the rain of salty spray that drenched us. But quite soon I began to feel queasy in the lower regions. I called back to the towering figure at the wheel, “Daddy, I feel sick. May we come back?” But Dad simply waved me down and sped on to the races, while I spent the rest of the morning retching helplessly. And so, along with Dad’s sweetness and kindness, I learned a tough lesson: a child’s discomfort would never halt the course of a naval expedition.

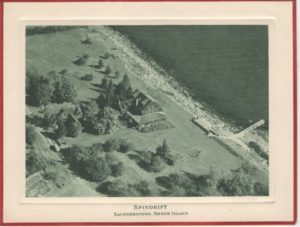

My father, James Rhodes Sheldon, had other interests, like hunting and ice-boating. Hailing from the South, he was a talented story teller and could keep us enthralled with tales that concerned his exploits and misadventures at sea. It was he who had seen the possibilities in redesigning the house that he had bought in Rhode Island. He found an old barn whose great oak logs and flat panels of weathered wood were inserted at intervals in the plaster ceiling and around the fireplace, giving our living room a warm, timbered look. Over the fireplace in sweeping italic letters he burned the name he had chosen for the house, Spindrift.

Living year-round in southern Rhode Island during the 1930s was a heaven-sent gift to children. Sparsely populated, the region offered sandy or rock-strewn beaches, lush meadows, and dense forests where three hundred years earlier the Narragansett Indians thrived on fishing and hunting. In our sprawling twenty-six-room home there was space for everyone. We were allowed to invite friends for extended visits. Some, like our young male cousins, came for months to spend the summer and learn to sail with us. Ranged in pens around the porch and the house itself, we had an incredible menagerie of animals. Dad was training carrier pigeons, Mother had acquired two handsome white borzoi, Russian wolfhounds that romped about the property like gazelles and eventually spawned nine puppies. My sister Betty and I kept a quantity of turtles for which we built an entire village of cardboard, chameleons that died sadly while sun-bathing in the Venetian blinds, and canaries with whom I carried on high-pitched communication. There was a small tiger kitty, which had somehow escaped the attention of our father, who detested cats. Brownie would climb the porch pillars, cross the roof and sneak into my bed at night. My one forbidden pleasure!

My father was opposed to the radio, which in his conservative view spewed little useful information. Not accustomed to hearing the news or weekly shows, we did not miss them. There were two pianos in Spindrift, a grand in the living room and an upright behind the kitchen, which we three girls would vie with one another to claim after meals. Practice was important to prepare for the weekly visits of our formidable Russian piano teacher who came by train from New York. An elderly woman of fiery temperament, Madame Drozdoff, among whose family of concert pianists several had played at Carnegie Hall, terrified me totally. Once when I played a bit of Chopin sloppily, she slammed her hand down on my fingers, “Not like that!”. I fled to the bathroom in tears, where I screwed up my courage before returning, for I passionately loved playing the piano. Later Mme. Drozdoff asked mother if I could go to New York to live with her family and train to be a concert pianist. “Oh, no! We wouldn’t want her separated from the family at the tender age of nine,” Mother hastened to say. I probably wouldn’t have liked it either, but now it occurs to me that that decision was typical of our upbringing. The path before us was already laid out; we were not to grow up to be artists or musicians, but models of upper-class society.

An event stimulated my interest in the affairs of Europe. In the early summer of 1938, at a cocktail party in Providence, my father met the skipper of a German vessel that had sailed across the ocean in a record twenty-eight days. My father, always welcoming to mariners, especially after a good dose of Bourbon, at once invited the visitors to use one of the moorings off Spindrift for as long as they wished. Captain Hans von Lottner duly sailed his fifty-eight-foot yawl, Roland von Bremen, down the bay and we soon had a troop of stalwart young Germans using the downstairs shower and taking us out for daily sails. At the moment my father was so keen on Germany that he gave a lavish party for the sailors on the expansive deck of our brand new boathouse. While the lovely Peggy was still in Italy, Betty and I, age fourteen and twelve, became mascots of the crew, sailing with them frequently. On board we oggled the grand ship with its tall masts, massive canvas sails, wide deck of teak and neatly coiled ropes. Yet how could one cross the vastness of the ocean on a vessel that would be tossed like a matchstick on the turbulent seas? The crew of foreigners, huge men, laughing and swapping jokes in garbled tones seemed like visitors from another planet.

The German yacht Roland von Bremen in 1936. After crossing the Atlantic Ocean in 1938, the yacht defeated a Bristol yacht in a race across Narragansett Bay. Afterwards, the Sheldons hosted the sailors at Spindrift (Wikipedia)

Sadly, Mother and Daddy separated in 1938. Mother kept Spindrift and I stayed with her. Summers when we came home from boarding-school things were not the same without Daddy. He had been the soul of our adventures, the instigator of all great projects. With him we had associated the delight of discovery, roughing it on the water, escaping from the strictures of my mother’s social world. But now that he was gone and World War II was underway, our world had turned upside down in a trice.

During the early 1940s as America’s participation in the war increased, strict “blackout” regulations were in effect on the coast and gas was scarce. In Saunderstown, most of the summer houses had been requisitioned by the Navy for service families, but Mother held onto our adored Spindrift as her only residence. Betty and I invited friends from school to spend the summer, Jane Ann Punzelt or Jo, my beloved first roommate at Saint Mag’s, and Betty’s friend from Puerto Rico at Bryn Mawr, the intellectual livewire, Herminia Malaret, known as Mickey. Betty was studying physics at Brown University, Mickey worked in a drugstore, and Jo and I were taking a chemistry course to prepare us possibly for a career in nursing. (My brother Irving was serving as a radar officer on a destroyer in the Pacific Ocean and my oldest brother Rhodey also served in the Navy during the war).

One time my roommate from boarding school, Eva Carey, and I decided to ride our bikes to Bailey’s Beach on Aquidneck Island. We rode over the recently-constructed Jamestown Bridge and took the Jamestown Ferry to Newport. Once in Newport, we biked to exclusive Bailey’s Beach and requested to be allowed on the beach. It was a gamble as we had not been invited and the beach allowed only members and their guests. Our doorman refused the request. “But my grandmother is Lizzie Chase of the Dunes Club in Narragansett,” I pleaded. This claim did not have the desired effect on the pompous doorman. Disappointed, Eva and I began to walk away back toward our bikes. Suddenly a newspaper photographer appeared. “Are you two the girls from New York?” he blurted out. “Yes,” I quickly responded; after all Eva hailed from New York State. But we suspected the photographer was looking for some New York debutants then visiting Newport. In any event, the photographer said, “Good. Can I take your picture?” The resulting photograph ran in a local newspaper. So the day was not a total disappointment.

During the summer of 1944, I rode my rickety old bike six miles to Narragansett on Saturdays to volunteer as a plane-spotter at the tower of the Town Hall, where three of us counted the motors of every plane we saw. We didn’t stop any invasions, though my high-living friend Bootch Bailey, after a binge on the town, apparently reported an “enemy aircraft carrier!”

Louise, with her friend Vernon Placke, helps to clean up the mess at Spindrift after the Great Atlantic Hurricane of 1944 (Elisabeth Sheldon Aschman Collection)

My grandmother Lizzie Chase was throwing her tiny weight wholeheartedly into the war effort. Every weekend she invited a dozen or so naval officers to dinner at the Dunes Club in Narragansett. The men being trained at Quonset Point at the time were known as ninety-day wonders, for they were undergoing speedy metamorphosis from business, education or local government to wartime usefulness. One wonders what rank-and-file service men thought of that! Some of the paunchy gents we observed belting down drinks in the Dunes Club bar didn’t look as though they’d ever seen the hull of a ship, but after all, the armed forces needed every body they could get, we reasoned. At seventy-five my grandmother was a fine dancer and a jolly hostess; the men vied with each other to dance with her. In my grandmother’s book officers were automatically “gentlemen,” but as a teenager at the time, I could have opened her eyes with a few wild stories. However, we did meet some very interesting young men attached to various flying squadrons who kept us alert to what was happening in their sectors of the war.

As meat rationing was extremely tight, we would invite the pilots we had met to dinner at Spindrift if they would bring the left-over steaks from their flights. Each crew member had two steaks per flight; those were the only steaks that we saw during the war.

Louise Sheldon at Bailey’s Beach. The photograph ran in a local newspaper in the summer of 1942 (Elisabeth Sheldon Aschman Collection)

With the labor shortage, all our servants had gone to work in factories; mother couldn’t afford them any more anyway. What a lark! We found this a splendid opportunity to take over the house and learn to cook. We therefore relegated Mother to such duties as buying groceries and making beds for guests. She was as delighted, as we were, for we hadn’t liked her scrambled eggs anyway. We put Betty, the scientist, in charge of the cooking department and the rest of us swabbed the decks.

I shall never forget Vernon Placke, a six-foot-six one-time telephone line-man from Montana and now a pilot, with a magnificent sense of humor, who came to Spindrift a number of times with his colleagues. We met fliers from many states, young men whose lives at home had been very different from ours. One of them, Chuck August, would be shot down over Casablanca, imprisoned by the Vichy French in Morocco, and return home. We had especially liked his squadron and would see its members year after year, as they tried out new planes —the F4F and F6F—and raved about each model in turn. One of the squadron members, Ed Seiler, in 1943 co-authored a popular book entitled Wildcats over Casablanca, which described in detail his squadron’s dangerous missions flying from the aircraft carrier USS Ranger over Morocco, including Chuck’s capture and escape. Sadly, Ed’s plane was shot down and he was killed in the Pacific in January 1945.

One night in Narragansett, we staged a wedding in an old blacked-out bar; it was all a game, in fun, acting out dreams. I married a flier, a nice, young man whose name I don’t remember and who, most sadly, was shot down and killed shortly thereafter. We were acting out dreams in an unreal, surrealistic sort of world where these men would appear one day and be gone forever the next. Perhaps it was good that we were so young. As teenagers we did not become romantically involved; we did not break hearts, nor did they break ours. We knew that only the moment counted. Later, after the war Chuck August, remembering his days in Rhode Island, married and settled in Newport. When we met, we would reminisce with him remembering the extraordinary days of the war.

A very different group of men turned up on a small Coast Guard boat on the bay, manned by six sailors and not much bigger than our former old rum-runner Skidaway, which had been sold along with the larger sailboats when Daddy left us. We had often seen the boat patrolling the bay inside the huge anti-submarine net, anchoring here and there along the shore. It was inevitable, I suppose, that we would meet the men on this craft, for they had made Spindrift their regular anchorage. (We heard a rumor that summer that an Italian submarine came to the “door” of the net guarding Newport and gave itself up, not wishing to make war any more. I recently learned that the rumor was not true, but that is the kind of rumor that circulated in those days.)

Early that summer Mother had gone to California because our beautiful and beloved older sister Peggy was marrying a Marine Corps flier. We were in the charge of an unflappable, permissive so-called “aunt” who failed to frown on anything we did. Some longtime residents, annoyed by the attention we were getting from the crew of the Coast Guard boat, complained that their “swimming waters were being polluted.” The vessel was anchored on the other side of the bay near Dutch Island lighthouse and the men rowed across to see us.

Meanwhile, Mother and our Aunt Peg were exchanging anxious phone calls. If we had baked a cake, we displayed a white towel from the lattice work on the porch. The one sailor on board who was not an officer or radioman was my special friend. It was he who had to row the rest of them across the bay, the incredibly beautiful bay, which seemed so often to be split by the glittering, golden path of a rising moon. No place could have been more romantic. My friend had apparently been a water-carrier at a factory in Bridgeport. Now I was going on to college; so there could be no match there, he said wisely. But I was learning that one didn’t have to have a college degree to be a worthwhile, decent person. Mickey lost her heart to the second officer, a delightful young man who had been to Harvard; sadly he disappeared over the horizon to marry his high-school sweetheart. Wartime threw people together and tore them apart. People, who would never previously have met, learned to know one another. World War II was such a leveler of society that the former, distinctly separate categories and stratifications almost disappeared in America.

Spindrift immediately before, during and after its demolition in August 2012—a sad day in the Sheldon family (Sheldon Family Collection)

There were more interesting encounters during our wartime summers in Rhode Island. In 1944, we were still sailing our Lawley 15’s, which were a great convenience to us in getting around, for Mother had only enough gas for one trip to town per week. One day sailing alone near South Ferry, I came upon a young man swimming far out in the water. There were no residents about besides older people not involved in the war. I waved and headed into the wind to see if he needed help, whereupon he said cheerily, “Guten Morgen” with a distinctly German accent. Mystified, I sailed away and only later learned that I could well have been instrumental in the escape of a prisoner of war!

Three camps of German prisoners had been set up in old army quarters near the mouth of Narragansett Bay, one of them at Fort Kearney in Saunderstown only a mile or so south of Spindrift. The camps had been organized to receive exceptional, democratically inclined prisoners who would be taught to take over positions in the American sector of occupied Germany; they were under the supervision of German-speaking officers in the U.S. Army. Betty had met Robert Kunzig, the captain in charge, who turned out to be a first-rate piano player and we were soon having parties with the German-American officers in charge and the instructors. Bob Kunzig had a repertoire of German war songs, as well as a talent for making up new ones; one that we sang frequently was based on a Nazi anthem, “Nationalsocialistische Volkswohlfahrt,” sung by all with great gusto and hilarity, with an emphasis on the last syllable.

One of the officers was a Swiss-American, Robbie Pestalozzi, from a famous family of educators. Another camp officer, a captain, was named “Walter” (pronounced “Valter”) from Germany, who asked me to take him for a sail. Valter had a predatory look and spoke garbled English, but I took him out anyway. I managed to crack him on the head with the boom as we set forth; undismayed, he thoroughly enjoyed the afternoon.

Quite uninformed about what was going on behind the scenes, we visited Fort Kearney for candle-lit dinners, served with fine wines by one of the prisoners, a former butler to a German baron, well-schooled in the art of entertaining. In Rhode Island we were experiencing a war that was more fascinating and illuminating than frightening. I found the international aspect of our meetings with the camp’s officers enthralling.

Perhaps in part due to my associating with Navy pilots at Quonset Point during the war, I later married a Navy Marine pilot. The exposure I had to German culture on Narragansett Bay also aroused my interest in studying abroad. After the war I majored in German literature and studied in Zurich, Switzerland, in 1946-47 (the first “junior year abroad” after World War II). Several years later I lived in Bad Godesberg and used my German extensively. I became an editor of LIFE Magazine’s international editions and foreign correspondent for United Press International and several other publications, taking advantage of my fluency in French and Spanish as well. Now retired, I spend most of my time in Arizona for health reasons, but with my second husband, Bob MacDonald, I spend part of the summer at a condominium in Hamilton, Rhode Island, with a lovely water view.

[Banner image: James Rhodes Sheldon operating Skidaway, a former rum runner from Prohibition times that plied Narragansett Bay, circa 1938 (Elisabeth Sheldon Aschman Collection)]

Sources

This article is largely based on Louise Sheldon MacDonald’s unpublished memoir, “Encounters with Myself” (May 2016), as well as to a lesser extent on her interviews and emails with Christian McBurney in 2016 and 2017.

Thanks are extended to Marjorie Johnston, the daughter of Elisabeth (Betty) K. Sheldon Aschman, for helping to gather many of the images for this article.

For more on Fort Kearney during World War II, see Christian McBurney and Brian L. Wallin, “The Top Secret World War II Prisoner-of-War Camp at Fort Kearney in Narragansett” in The Online Review of Rhode Island History (April 22, 2015). Here is the link to the article:http://smallstatebighistory.com/the-top-secret-world-war-ii-prisoner-of-war-camp-at-fort-kearney-in-narragansett/