The year 2017 was another good one for the publication of Rhode Island history books. While we cannot possibly review all of them, I review several of them below and Russell DeSimone will review several more in an upcoming article. I will then end up reviewing three recent historical novels with Revolutionary Rhode Island as the backdrop. Do keep them in mind for the holidays.

Naturally, we could not review our own World War II Rhode Island (History Press, 2017), by Christian McBurney, Brian L. Wallin, Patrick T. Conley, John W. Kennedy, and Maureen A. Taylor. I will say we authors are thrilled with the positive feedback we have received and proudly add that Wakefield Books alone has sold more than 120 copies of the book!

Here are some others, which are available at many Rhode Island bookstores and history museum gift shops, and all of them on Amazon.com.

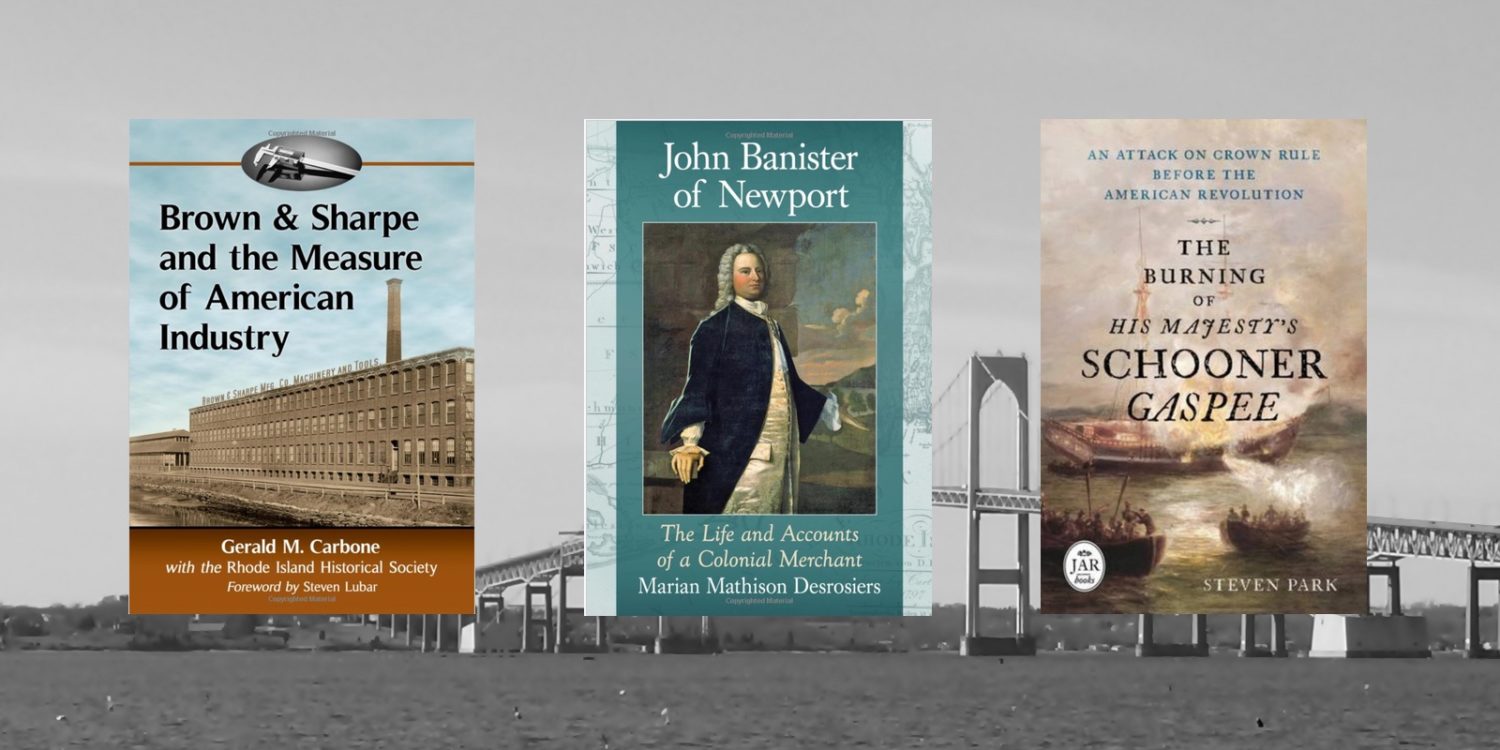

Gerald M. Carbone. Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry (McFarland, 2017) ($39.95). In my view, this is the most important Rhode Island history book of the year. It is the story of what became arguably the state’s most impressive industrial enterprise, founded in 1849 by clockmaker Joseph Brown (no relation to the family line of Moses and John Brown), who tinkered with and began inventing new machines, and Lucian Sharpe, who would guide the company in its crucial formative years in an age of great technological change. The company would grow into one of the nation’s most important machine tool manufacturers—machine tools are used to make other machines. In its early years, the manufacture and sale of sewing machines financed the company’s ventures into machine tools. I suspect Brown & Sharpe employed more Rhode Islanders, many of them skilled workers, than any other private company in the state’s history. Thus, the book, spanning from 1849 to 2000, is a history of the state, its workers, unions and state industry. Wars and the rise of automobiles and aircraft helped fuel Brown & Sharpe’s growth. The impact of the various wars, from the Civil War, to the Spanish-American War and up to the Korean War, was startling. For example, the company employed more than 7,600 workers during and shortly after America’s entry in World War I, but when war orders dried up, its workforce shrank temporarily to fewer than 1,000. It then recovered in the economic boom of the 1920s. Of course, many women were hired, including those operating complex machines, during both World War I and World War II. The company did not hire its first black worker until the 1920s, and the International Association of Machinists did not admit blacks until forced to do so by federal law in the early 1940s. In 1965, following the suburbanization trend, Brown & Sharpe moved from its conglomeration of buildings sprawled on Smith Hill in Providence to a new facility at Precision Park in North Kingstown. Providence lost its second largest taxpayer, behind only Narragansett Electric.

The book ends, sadly, with one of the longest strikes in American labor history starting in 1981, resulting from a breakdown in relations between owners and workers at a time when New England manufacturers were facing unprecedented worldwide competition. The union voted down pay increases of 9%, 10% and 11%, which seems amazing today. The union resented management’s efforts to increase productivity by taking away certain seniority rights of union workers on the workshop floor. At the time, Rhode Island was one of two states (New York was the other) that paid union strikers compensation, which no doubt helped to extend the bitter strike. According to Carbone, many of the strikers would have lost their jobs in the near future anyway, due to the near collapse of the machine tools industry and the tepid U.S. economy in 1982. The strike did not end until 1997, when the final litigation was resolved.

Despite the author’s background of writing from the labor point of view, Joseph Brown’s descendants nonetheless allowed him unfettered access to write the complete, accurate, and unvarnished truth of their family company. The decision was an excellent one, as Gerald Carbone has created a fine and balanced book, with assistance from the Rhode Island Historical Society. Despite Henry Sharpe, Sr. and Henry Sharpe, Jr. opposing the rise of unions and the state legislature mandating shorter work days and holidays, Carbone appreciated that they were ahead of their times in paying and treating their workers well in other ways. Carbone’s affection for the Brown and Sharpe families seeps through his excellent book.

Click here to buy Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry on Amazon.com.

Marian Mathison Desrosiers, John Banister of Newport, The Life and Accounts of a Colonial Merchant (McFarland, 2017) ($32.95). The author, a professor at Salve Regina University in Newport, has penned the best book on a colonial merchant from Newport, during the second and third quarters of the eighteenth century, when the port was one of the top five commercial centers in the mainland thirteen colonies. John Banister (1707-1767), an immigrant from Boston, became the most prominent merchant in Newport in the mid-eighteenth century (the Jewish merchant Aaron Lopez became even wealthier, but he operated mostly in the 1760s and 1770s, after Banister retired). Banister owned and built the town’s most important private wharf, Banister’s Wharf, centrally located on the waterfront.

Relying on Banister’s merchant records and correspondence, Desrosiers has compiled and described the varieties of merchandise that Banister both imported and exported. Interestingly, his most valuable export, timber, did not even come from Rhode Island, showing how merchants in the colony had to scramble to get ahead. While Banister is often said to have financed many slave trading voyages to Africa, Desrosiers could find no evidence of it in the 1740s, although he methodically recorded the details of one he financed from 1751-1752. At the same time, Banister’s account books show that he built slave ships for several Liverpool slave traders and did not hesitate to purchase slaves for his own use in Rhode Island. Other mercantile efforts include his role in the emergence of shipbuilding along the Taunton River, financing privateers during wartime, lending money to fellow merchants, and dealing with the costs of marine insurance and British customs laws.

The author also examines the family’s personal expenses as privileged members of the gentry and Banister’s outlays to develop the Arnold-Pelham real estate in downtown Newport and two 150-acre farms in Middletown. This most welcome work, for historians and for readers interested in colonial Newport, deepens our understanding of Newport merchants and the world in which they lived in during the decades prior to the American Revolution.

Steven Park, The Burning of His Majesty’s Schooner Gaspee, An Attack on Crown Rule Before the American Revolution (Westholme, 2016) ($22.02). The most famous incident occurring in Rhode Island in the years leading up to the American Revolution was the burning of H.M.S. Gaspee shortly after midnight on June 10, 1772 off Namquit Point. The British ship was a sitting duck, after its commander, Lieutenant William Dudingston, grounded his vessel on shoals while unwisely chasing in shallow water a Rhode Island vessel he suspected of smuggling. Dudingston was also despised in Rhode Island, as he had used his armed schooner to attempt to enforce trade duties and import laws on a population that depended on maritime trade and was renowned for flaunting such rules. Before the sun would rise, a boatload of Providence merchants, led by John Brown and Abraham Whipple, seized the British schooner from its crew, burned it to the waterline, and left Lieutenant Dudingston writhing in pain and in his own blood, suffering from a wound to his groin from a musket shot.

Steven Park, a professor at the University of Connecticut, has undoubtedly penned the most accurate description of both the incident itself and the long but ultimately fruitless effort by British authorities to discover and punish the perpetrators of the crime. And yet this book is a lost opportunity. The author provides no color to the times and fails to provide any background for the wonderful cast of characters that includes John Brown, Abraham Whipple, Nathanael Greene, Admiral John Montague, and Governor Joseph Wanton. What is more, the stirring events are described in business-like terms, without a hint of drama. This is in stark contrast to the Pulitzer-Prize winning book An Empire on the Edge, How Britain Came to Fight America, by Nigel Bunker, who used the Gaspee incident as a focal point of his book and described it as an important event leading to the rebellion by Patriots and ultimately to the Declaration of Independence. Bunker wrote, “So the raiders were more than a rabble, and we cannot dismiss the attack on the Gaspee as just another riot. A military operation three years ahead of its time, it arose from a matrix of ideas, formed in the circle that surrounded Stephen Hopkins. . . . [John Brown wrote,] he attacked the ship because the lieutenant was acting unlawfully by failing to show his commission to the governor and by ignoring the local judges.”

I found the most interesting part of Park’s book a clever chart the author created ranking the most popular pamphlets in America in the years leading up to 1776 (since sales figures were not available, ranking them is not easy). One of the top pamphlets, a sermon penned by an obscure but fiery Congregationalist preacher from Massachusetts named John Allen, focused on the Gaspee event and its aftermath in a scathing attack on British imperial rule.