Throughout the village of Wickford, Rhode Island’s three centuries of existence, thousands of people have come and gone. Lives of all sorts have played out in Wickford and its nearby environs. Some have led simple and ordinary lives; a few have had amazing and extraordinary lives; most have led lives that fall somewhere between these extremes. None of them, however, led a life like Mabel Hayward’s. Mabel’s life both defied convention and defies our imagination. It played out like a tale told by a gifted creative storyteller who never fails to dazzle. Yet Mabel’s story really happened. Readers who enjoyed the movie “The Sting” will love Mabel’s tale. She was a con artist extraordinaire. She tried to pull off the boldest con of the twentieth century – perhaps the boldest ever imagined. But we are rushing the tale here. Let’s start by examining Mabel Hayward’s Rhode Island roots.

Born Mabel Davis, she left few footprints on the historic record until her marriage to Charles Hayward and their subsequent arrival at the tumble-down old Beriah Lawton farmhouse on the corner of Beach Street and Steamboat Avenue just outside the village of Wickford. The house, long since demolished, sat along the right-of-way for the Newport & Wickford Rail line. The trains using this railroad brought the wealthy through the village on their way to the Poplar Point steamship dock and a ride on the steamer General to their summer playground in Newport. Charles’s mother, a member of the large Lawton clan that lived in the area, had previously owned the old farmhouse. Charles and Mabel settled in and began married life together.

The Haywards soon had two children, Theodore L. (known as Teddy and named after his grandfather Theodore Lawton) and Edna. Teddy and Edna had, by all accounts, an unremarkable childhood until the event that caused so much widespread unemployment and suffering in the United States: The Great Depression. Probably jobless and feeling a sense of worthlessness, it appears Charles departed the state, as he disappears from the historic record thereafter. This was a sad scene that, unfortunately, played itself out all across America. Mabel was left with two hungry children and her wits, and not much else.

Hard times require folks to make choices they might never otherwise consider. Perhaps that was the case with Mabel. Word got around the quaint and historic village of Wickford that Mabel and her kids often went on unexplained trips and suddenly had more money than they ever had previously. Small towns being what they are and folks being nosey like folks still are today, it wasn’t long before neighbors whispered across backyard fences and clotheslines about Mabel’s newfound prosperity. The rumors of strange doings were finally confirmed when a wire arrived from the New York City Police Department requesting the presence of Mabel’s local relations at a precinct house in the “Big Apple” to bail out Mabel and her two children.

It seems that the three had a habit of taking a train down to the big city and setting up on a busy city street corner where the musical Mabel would pretend to be a blind violinist and the little moppets would dance to her tunes, soliciting donations for their efforts.

As can be imagined, the request caused no little bit of a local ruckus across the small town of Wickford. The excitement over Mabel’s indiscretions subsided quickly as folks continued to deal with their own Great Depression-related problems. Yes, following the return of Mabel and her children after being bailed out in New York, there must have been snickers and snide comments, but that eventually died down. Mabel’s appetite for easy money, on the other hand, did not subside so quickly and this is where the con-to-end-all-cons enters the picture.

Around the same time that Mabel’s exploits were being whispered about in little Wickford, the country’s attention was glued to the fight over who would inherit John Gottlieb Wendel’s fortune, estimated at $150 million. Wendel had died without a will. The dispute ended up in state court in Mabel’s old haunt, New York City.

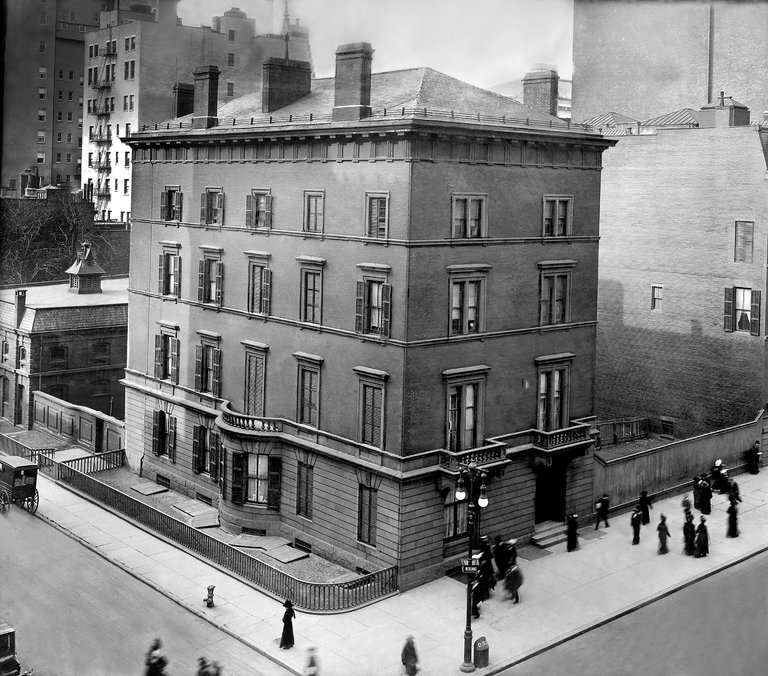

Wendel’s grandfather had been John Jacob Astor’s business partner and, some say, the brains behind the two-man team that amassed a fortune the likes of which no one before had ever accumulated. The grandfather adopted the mantra, “Buy, but never sell, New York real estate.” Wisely, he let New York City grow around him. His grandson carried on the family tradition, residing at the family’s towering four-story mansion on Fifth Avenue at Thirty-Ninth Street. Every newspaper and every newsreel of the day availed the Depression-stricken masses of the story of the bachelor millionaire who had died intestate and the ensuing high-stakes squabble over his fortune.

An equally intriguing part of the back story behind the Wendel estate’s massive investments was the rather unflattering portrait that emerged of John Wendel. To say he was eccentric would be putting it mildly. He did not allow any electricity, radio or phone in the house. There were no elevators or dumbwaiters in the four-story mansion.

Moreover, Wendel had an intense hatred of the institution of marriage. He did not want any “strangers” sharing in his wealth. He refused to execute a will, saying that he “didn’t want any damned lawyer making money out of my property.” His iron rule against matrimony extended to his siblings, six sisters, spinsters all, who spent their days cloistered in their drab hermitage of a home in downtown New York City. All wore black high-necked dresses that Wendel required them to sew, and none could wear jewelry. Gossip columnists of the day described the residence as “a grim castle of celibacy haunting the gay mid-channel of Fifth Avenue.”

This had all the makings of a great story: money, celebrity, eccentricity, and sex (actually the lack thereof). The whole country tuned in to the controversy of who would inherit Wendel’s estate.

Mabel Hayward followed the story as well. Soon previously unknown Mabel had concocted a tale that put her in the middle of the dispute over the money and grabbed the nation’s imagination. She claimed that old John Wendel had not been a bachelor after all. Why, according to her, as a young man he had secretly married Mabel’s grandmother, Hannah Halt, whom he had met and wooed while he was a student at Columbia University. Wendel’s powerful father, according to Mabel, would have none of it. He had the marriage annulled and all records of it expunged; wealthy and powerful men, it was believed, could do such things. However, the father did not move fast enough to avoid Hannah becoming pregnant with John’s child. Hannah gave birth to Bertha, who, according to Mabel, would later become Mabel’s mother. Conveniently for Mabel, all involved in this tale of intrigue and woe were now deceased, except, of course, for Mabel and her two children, Teddy and Edna—the purported great grandchildren of one of America’s richest men.

Sometimes the brashest of schemes are the ones that succeed. This one almost did. The media of the day grabbed hold of this story and played its tale of rags to riches to the hilt. Mabel flawlessly performed her role (which was probably a piece of cake compared to the blind violinist gig), always placing her children in the spotlight and playing the dutiful mother in the background.

On March 23, 1931, the New York Daily News reported that the $150,000,000 Wendel will was filed for probate that day. The article boldly announced, “The claim of the Hayward family—Mrs. Mabel, daughter Edna and son Teddy—grand and great-grandchildren of John Gottlieb Jr., undoubtedly will be the greatest obstacle to probating the will.” It seems Mable retained a gullible Providence attorney; presumably, he would be paid from the proceeds of her award. The article continued, “Col. William W. Moss of Providence, attorney for the destitute Wickford, R.I., Wendel descendants, interviewed Mrs. Mabel Hayward during the weekend and announced he would take immediate steps for an accounting of the Wendel Jr. estate.” The next day, the Brooklyn Eagle reported that “In Providence, R.I., Mabel Hayward has a yellow slip of paper to prove” her claim; the contents of the yellow slip of paper were not revealed.

A photograph purportedly of Teddy Hayward that appeared in the New York Daily News, March 22, 1931. The young man shown is quite handsome.

For a time it appeared as if Mabel might succeed. The little village of Wickford was abuzz with reporters. At movie houses across America theatergoers could see the saga unfold on the screen before them during the opening newsreels. Famous syndicated New York columnist Jane Dixon, a woman who specialized in male dominated topics such as boxing and baseball, called the deliciously lurid tale “Dickensonian” and labeled the deceased millionaire “a martinet” (meaning a strict disciplinarian). Many in America were convinced that Mabel, Teddy, and Edna were on their way to Easy Street.

Having known Mabel, the folks in Wickford were understandably skeptical of her Cinderella story, as was the constabulary in the “Big Apple.” It took time, but eventually Mabel’s story was debunked. Her fifteen minutes of fame over, she faded into the background as America’s focus switched to a looming world war.

Mabel Hayward, the woman who almost became a “made” millionaire, lived out the remainder of her days in a tiny little cottage on Steamboat Avenue, a stone’s throw from where the big Lawton farmhouse once stood. She is buried in an unmarked grave in one of the Lawton lots at nearby Elm Grove Cemetery. As the screen fades to black, cue the Scott Joplin tune “The Entertainer” and conjure up an image of two ragamuffin kids dancing a jig while a “blind” woman with a Cheshire cat grin plays a hearty tune on the violin.

[Banner image: The Wendel mansion in New York City]

Bibliography

Vital Records – Town of North Kingstown

Wickford Standard Times – microfilmed editions of the period

Jane Dixon, “Women Behind The News,” North American Newspaper Alliance, March 20, 1931

New York Daily News, March 22, 1931

Brooklyn Eagle, March 23, 1931

Diaries of Harriet Smith – unpublished manuscript in private hands whose owner desires to by anonymous

Jay Robert Nash, Zanies: The World’s Greatest Eccentrics (The Roman & Littlefield Publishing Group, 1982).