“The muffled drum’s sad roll has beat the soldier’s last tattoo.”[1]

Today the death of an American service member initiates a long process beginning with the terrible knock on the door and requiring the government’s full support in helping the family during that very difficult time. During the Civil War and up through the Vietnam War, no such process was in order.

In the Civil War it generally fell to a member of the soldier’s company to write a letter to inform the family, and the family was responsible to pay the cost of having the remains shipped home. Because of the nature of Civil War deaths and combat, many families never learned about what happened to their loved ones and searched for years for information. Well over half of all Civil War soldiers buried in national cemeteries are listed as “Unknown.”

Between September 10, 1862 and June 9, 1865, 1,184 men served in the Seventh Rhode Island Volunteers. This includes 963 original members of the regiment, and 226 veterans who transferred in the fall of 1864 from the Fourth Rhode Island Volunteers. Of this number, an appalling 104 were killed in combat or died of wounds, and a further 110 died of disease and in accidents in the service. Not counted in the figure are 23 men who died immediately after being mustered out of the service and whose deaths are directly attributable to their service in the Seventh Rhode Island (based on a statewide survey of Civil War soldiers, this figure is more than likely to rise). In heavy fighting at Fredericksburg and the Overland Campaign, and through diseases such as typhoid, dysentery, pneumonia, malaria, and yellow fever, in Virginia, Mississippi, and Kentucky, the losses the Seventh sustained were felt in every Rhode Island community. Nearly every Rhode Islander knew someone who died in the Civil War.[2]

Readers of my works recall the deep research I have done into the soldiers of Company A of the Seventh Rhode Island Volunteers. The company of 100 men was raised among the mill workers and farmers of Westerly, Hopkinton, Richmond, and Charlestown in July and August 1862, and the men of Company A left behind a rich written record.[3]

After leaving Rhode Island on September 10, 1862, the Seventh spent several weeks in Washington before being sent to join the Second Brigade, First Division of the Ninth Army Corps, which was then camped in Pleasant Valley, Maryland, not far from the battlefield at Antietam. Almost immediately upon leaving the state, many of the members of the regiment, including my own great-great-great uncle, Alfred Sheldon Knight of Scituate, became ill with diseases such as typhoid, pneumonia, and dysentery caused by poor food and water, overcrowding, and unsanitary conditions.

The first two deaths in the regiment occurred on October 5, 1862, when Charles Baker Greene of Company A, a nineteen-year-old farmer from Ashaway, and twenty-one-year-old John F. Brown of Exeter, died of typhoid. Brown passed at a hospital in Washington and Baker died in Frederick, Maryland. Because these first two deaths occurred in hospitals away from the regiment, the soldiers were mourned by their comrades, but the men in the ranks did not experience the loss first hand.[4]

Immediately upon arrival at Pleasant Valley, a typhoid epidemic erupted through the ranks of the Seventh, sending many to the regimental hospital, while the worst cases were discharged and sent back home to Rhode Island. The Seventh was blessed to have three very competent doctors assigned to it, including Major James Harris who had served as a volunteer surgeon in the Crimean War and had been captured at Bull Run rather than abandon the patients he was treating. Despite the best efforts of these three doctors and Stephen Peckham, a gifted Brown University chemist who acted as the regimental hospital steward, there was nothing this medical team could do to stem the typhoid epidemic. Soon the disease claimed the first victims to die in the Seventh’s camp: two privates from Company A.[5]

One of these men was Gideon Franklin Collins, a married farmer from Hopkinton who had enlisted in Company A on August 8, 1862. He was typical of many of the men from rural Rhode Island who had never had exposure to the diseases that were hitting the regiment hard as they adjusted to field service. In a letter of condolence to the family of Charles Baker Greene, one of the Seventh’s first victims, Private Edwin R. Allen, later the commander of Company A, wrote on October 15, 1862: “Franklin Collins has been quite sick, but is more comfortable today- he is pale and poor- in the Regimental hospital.” Only two months after leaving Hopkinton, he was dead at the age of twenty-four, a victim of the typhoid epidemic spreading throughout the Pleasant Valley camps of the Army of the Potomac.[6]

In The Seventh Regiment Rhode Island Volunteers in the Civil War: 1862-1865, William Palmer Hopkins provided this brief sketch of Collins’ life:

Gideon Franklin Collins, son of Welcome and Sallie Collins, was born in Greenfield, Pa., Oct. 19, 1837, but his boyhood was spent in Hopkinton, R.I. In early life he became an active church member, and lived a consistent life, as his many friends have testified. On a certain day at Camp Bliss he had a fainting fit after which he never was entirely well. His appearance was different, and though he performed all his duties and seemed quite well at times, those periods were brief. Finally, he was obliged to go to the hospital, and it soon became evident he had typhoid fever. Up to within a few days of his death the doctor gave hope of recovery, but it was evident his strength was failing fast. None could be more patient than he. The night before he died he told one of the female nurses that he felt a great change coming over him, yet he remained perfectly composed and happy. He died at Pleasant Valley, Md., Oct. 19, 1862, on his twenty-fifth birthday. He left a widow and one child.[7]

Only the day before, George Washington Gardiner, another twenty-four-year-old Hopkinton private in Company A also died of the disease in the Seventh’s camp.

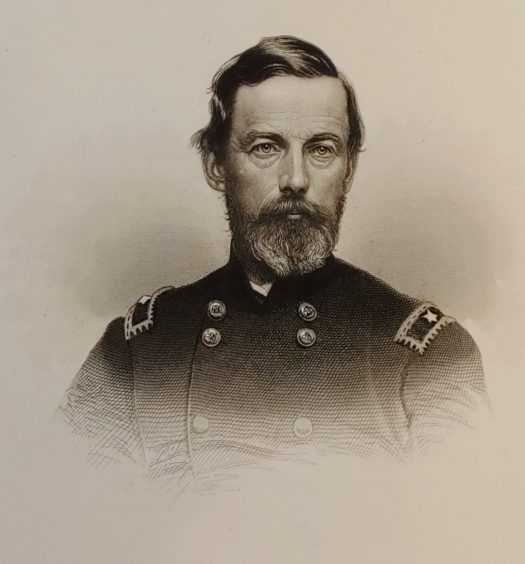

While two soldier’s deaths over the course of the war had little impact on the regiment, especially as the toll of the Seventh’s service increased, the first fatalities in the regiment’s camp hit hard. Collins and Gardiner were well known by their fellow soldiers from Hopkinton, and Colonel Zenas Randall Bliss of Johnston, a West Pointer and the Seventh’s commander, decided that a fitting ceremony be held to honor their memory. In his postwar memoirs, he wrote, “It was the first death in our regiment, and I desired to show every possible respect to the deceased, I ordered out the whole regiment and marched it to the grave in a little grove and formed it in a square, and the chaplain preached for nearly two hours, till everyone was tired out.”[8]

The funeral, the only one ever held as a regiment, was long remembered by the men of the Seventh. Charles P. Nye of Richmond wrote home to Benjamin Pendleton in Hopkinton about the event, “The 9th New Hampshire Brass Band led the prosesion to the grave followed by our drum band and thin [then] eighteen of Company A with reverse arms then the cops [corpse] and then the rest of com. A, than [then] came the whole Regiment with commissioned Officers in the rear the text was taken in the 5 chapter of Jacob 60 verse after the cops [corpse] was then lowered in to their graves three vollys was fired over their grave and then we returned to our quarters. It was the Solomens [solomnest] sene [scene\ that I ever witness.”[9]

Charles P. Nye of Richmond wrote a letter revealing how deeply affected he was by the regiment’s first deaths.

Two days before the Seventh’s baptism of fire at Fredericksburg, the Narragansett Weekly of Westerly published this letter of condolence to the wife of Private Gideon F. Collins in the December 11, 1862 edition. The editor of the Weekly wrote, “The following letter will interest many of our readers, who are acquainted with the write and the subject.”[10]

Pleasant Valley, Md.

Oct. 21st 1862

Mrs. Gideon F. Collins,-

It becomes my painful duty to inform you of the death of your husband, which took place on the morning of the 19th instant, at 7 o’clock. I am satisfied that he has never been entirely well, since the day that he had a fainting spell at Camp Bliss. His appearance has been different from what it was before. This is the opinion of all of the boys who were acquainted with him. Sometimes it is true, he seemed pretty well and went through with his duties; but it would be only for a short time.

He was finally obliged about two weeks ago, to go to the hospital, and in a short time, it was evident that he had the typhoid fever. From this time, he had no appetite, and rapidly lost flesh. His fever was apparently light, and slow its operation was but too sure. Up to within a few days of his death, the Doctor gave some encouragement of his recovery; but it was evident that his strength was failing very fast.[11]

The night before he died, while poor George Gardiner, who died in the early part of the night was in his last agonies, Miss Gibson, one of the female nurses, knelt down between them, and offered a fervent prayer for them both. Your husband listened attentively, but said nothing at that time. In the course of the night he told another nurse, that he felt there was a great change, and he appeared to know that he was dying. He was perfectly composed and happy as far as could be ascertained from the few remarks he made. I think I have never seen any one more patient in sickness. One of the surgeons was with him when he died. He told me he never saw a man die easier; and a lady who was present, told me that he died without a struggle or convulsion. I saw him every day during the latter part of his sickness; sometimes, two or three times a day. I think he longed for home, and the loved ones there; though he would never admit that he was home-sick. But who would not feel home-sick when so reduced in physical strength?[12]

I must say, that the boys were very kind to him-especially Aldrich C. Kenyon [12] and George A. Thomas. [14] In fact he was a favorite among his acquaintances. We buried him and George Gardiner with military honors on the 20th at 4 p.m. The place selected for their graves is on the edge of the woods, north-west from our camp. They lie between two oak trees, about one rod apart, and a beautiful dog-wood spreads its branches over their quiet resting place. Every one I have heard speak of it says that it is a beautiful place for a burial.

The Chaplain, Rev. Mr. Howard, [15 preached from 2 Cor v. 20: “Now then we are ambassadors for Christ,” & c. The Chaplain wishes me to assure you of his deepest sympathy; also Capt. Leavens [16] and Lieut. Kenyon. [17] Capt. Leavens has taken charge of all valuables your husband had in his possession at the time of his death, as well as of some that he had entrusted to others before he died. He has turned over his knapsack and clothing to the Quartermaster of the regiment, [18] to be paid for when his monthly pay shall be drawn. The other valuables he has sent in Lieut. Inman’s trunk. They will be forwarded to T.T. & E Barber of Brand’s Iron Works, [20] through whom you will receive them in the time.

Your husband, I believe gave his wallet and money (amounting to five or six dollars) in charge of Aldrich C. Kenyon, who no doubt will account to you for them. I do not know what I can add that would comfort you in your bereavement. It is my fervent prayer, that the Good Shepherd of Israel will be to you a tender husband, and a father to your orphan child; and that you and all of the other relatives and friends, may find that consolation in the gospel which it were vain to look for elsewhere.

Your sincere friend

Joseph W. Morton [21]

Joseph F. Morton wrote a detailed letter home to the wife of Gordon Franklin detailing his friend’s last days

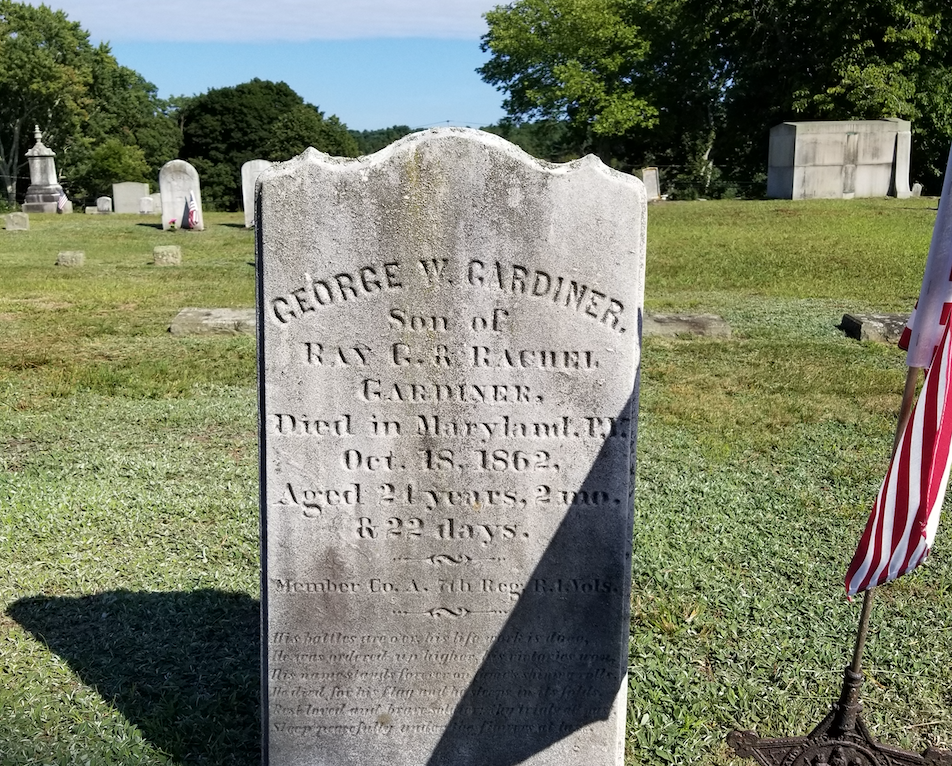

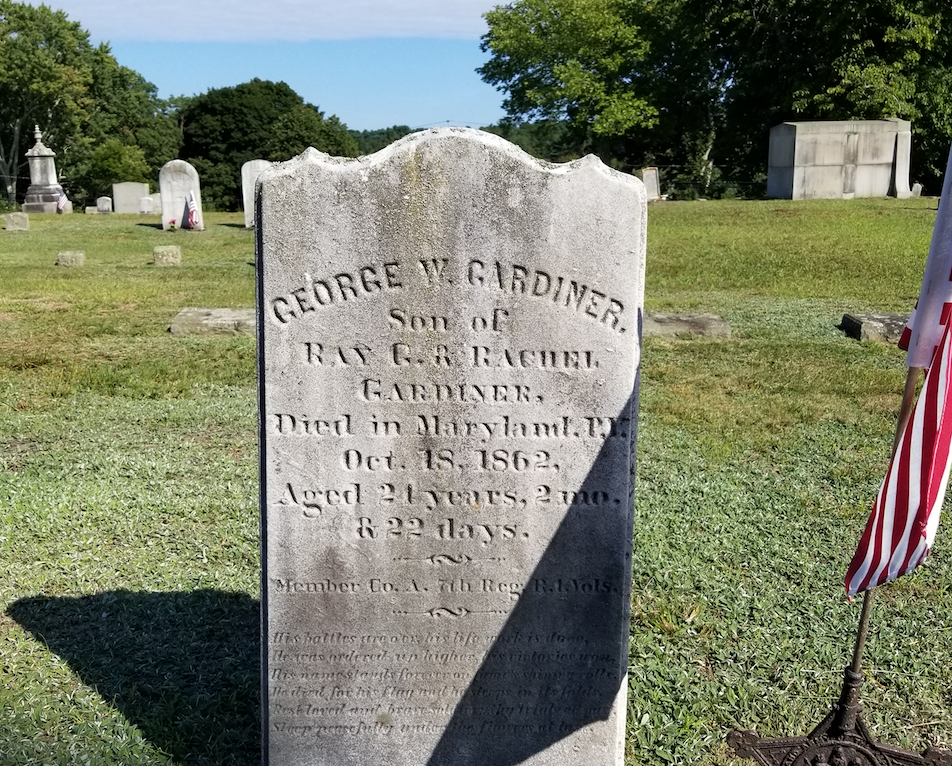

Unfortunately, this would be just one of many such letters sent to Hopkinton during the Civil War years, as one out of every six men from the town perished in the war. The remains of Private Gardiner were returned to Hopkinton and buried in the Pine Grove Cemetery in Hope Valley. It is unknown where Private Collins is buried, as he does not have a memorial stone in Hopkinton or a burial in the Antietam National Cemetery.[22]

George W. Gardiner’s grave in Pine Grove Cemetery in Hope Valley, Rhode Island, Sept. 2018 (the Author)

With the death of her husband, and with a young son, Franklin M. Collins, to support, Susan E. Collins knew that she could turn to the government for help under the provisions of the Pension Act of July 14, 1862, granting pensions to the widows and orphans of volunteers who died in Federal service. She filed on January 9, 1864, and on October 11, 1864, was receiving a small pension of eight dollars per month. Both Captain Leavens and Lieutenant Kenyon wrote affidavits in support of Mrs. Collins’s relief. Leavens wrote, “I have no doubt that the fever was contracted from exposure while in the line of his duty in the Service of the United States.”

Susan Collins remarried Damon Young of Bristol on September 7, 1870, thus vacating her claim to a pension, while her son continued to receive eight dollars per month until he turned sixteen in 1876. With the death of her second husband, Susan remarried a third time to George T. Collins of Moosup, Connecticut, in October 1896; George Collins died in 1903. Neither one of her other husbands served during the Civil War. Under the provisions of a generous Federal pension act in 1903, Civil War widows who had remarried, but whose subsequent spouses had died, could refile a pension claim based on the marriage to the spouse who had died as a result of his Civil War service. As such, Susan, now sixty-seven and living in Ashaway, refiled for a pension based on her marriage to Gideon F. Collins in February 1904. Mrs. Collins was again approved and received a Federal pension of twelve dollars per month until her death on May 13, 1915 when she was again “dropped from the rolls.”[23]

[Banner Image: George W. Gardiner’s grave in Pine Grove Cemetery in Hope Valley, Rhode Island, Sept. 2018 (the Author)]

End Notes

[1] Theodore O’Hara, “The Bivouac of the Dead,” in Thomas R. Lounsbury, ed., Yale Book of American Verse, 1912.

[2] Seventh Rhode Island Volunteers, Descriptive Books, Rhode Island State Archives. William P. Hopkins, The Seventh Regiment Rhode Island Volunteers in the Civil War: 1862-1865. (Providence: Snow & Farnum, 1903), 311-531. The figures of enlistments and deaths in the Seventh Rhode Island is based on a very, very careful study of all available soldiers’ letters, town hall records, pension papers, and cemetery visits by this author. These casualty figures are the most comprehensive available to date.

[3] Narragansett Weekly, August 7, 1862 and August 21, 1862.

[4] Kris VanDenBossche, ed. Pleas Excuse all bad writing: A documentary history of Rhode Island during the Civil War era 1861-1865. (Peace Dale, RI: Rhode Island Historical Document Transcription Project, 1993), 62-67. Alfred Sheldon Knight, Civil War letters, author’s collection.

[5] VanDenBossche, Please Excuse, 62-67. Stephen Farnum Peckham, “Recollections of a Hospital Steward in the Civil War,” Newport Historical Society, Newport, RI. Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 332-335.

[6] Company A, Seventh Rhode Island Volunteers, Descriptive Book, Rhode Island State Archives. VanDenBossche, Pleas Excuse, 65-66.

[7] Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 381.

[8] Zenas Randall Bliss, The Reminiscences of Major General Zenas R. Bliss: 1854-1876. Edited by Thomas T. Smith, Jerry D. Thompson, Robert Wooster, and Ben E. Pingenot. (Austin: Texas State Historical Association, 2007), 312-313.

[9] Bliss, Reminiscences, 312-313. Charles P. Nye to Benjamin Pendleton, October 22, 1862, Rhode Island Historical Society.

[10] Narragansett Weekly, December 11, 1862.

[11] Major James Harris of Providence was the regimental surgeon of the Seventh. One of the most respected physicians in the army; he had graduated from Brown and the Philadelphia College of Medicine and Surgery. He served as a volunteer surgeon to the Russian Army in the Crimean War. In 1861 he served as assistant surgeon of the First Rhode Island Detached Militia and was captured at Bull Run rather than abandon his patients. Commissioned into the Seventh Rhode Island, he eventually became the medical inspector of the Ninth Corps. After the war Harris moved to Japan and devoted himself to the study of anthropology; he lived in Japan for the rest of his life and died around 1900, having never returned to the United States. Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 332-333.

[12] While the Seventh had several male soldiers detailed to its hospital detachment in a role that would today be considered that of a nurse’s aide, no female nurse is known to have served in the Seventh. See Peckham, “Recollections of a Hospital Steward.”

The two assistant surgeons of the Seventh Rhode Island were Dr. William Alvestus Gaylord of Providence who was a graduate of Harvard Medical School and Dr. Albert Gallatin Sprague Jr. of Warwick who had attended Jefferson Medical College and had served three months previously in the Tenth Rhode Island. Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 333-334.

[13] Aldrich C. Kenyon was a married twenty-seven-year-old farmer from Hopkinton who enlisted on August 7, 1864. Wounded at Bethesda Church on June 3, 1864, he was mustered out on June 9, 1865. After the war he resumed farming in Voluntown, Connecticut where he is buried. Company A Descriptive Book.

[14] George Amos Thomas was a married twenty-eight-year-old blacksmith from Hopkinton who enlisted on August 7, 1864; He died of typhoid on April 14, 1863 at Baltimore, Maryland. Company A Descriptive Book.

[16] Harris Howard, also known as Harris Howard Tinker, was the chaplain of the Seventh Rhode Island. A native of Illinois, he was a forty-two-year-old Methodist-Episcopal minister in Providence when the war broke out. Unpopular with the troops, he resigned in July 1863 and later moved to Maine and Kansas City, Missouri where he died of paralysis. Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 334. Peckham, “Recollections of a Hospital Steward.” Bliss, Reminiscences, 312-313.

[17] Lewis Leavens of Hopkinton commanded Company A and recruited the Hopkinton men for the unit. Born in New York City in 1823, by the outbreak of the Civil War he was a mill owner in the village of Canonchet. Slightly wounded at Fredericksburg in December 1862, he resigned his commission and returned to New York City, where he resided for the rest of his life. Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 349-350.

[18] David R. Kenyon of Richmond was a twenty-nine-year-old married “manufacturer” who recruited most of the Richmond contingent for Company A. Wounded in the leg at Fredericksburg; he was promoted to captain of Company I, but resigned in March 1863. After the war he continued working in the mill industry, and served in a variety of civic officers; he died in 1897. He is buried in Wood River Cemetery, Richmond. Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 349.

[19] The original quartermaster of the Seventh Rhode Island was Lieutenant Dean Smith Linnell of Providence. He had traveled to California during the Gold Rush. Linnell had served in the Tenth Rhode Island in the quartermaster department, and was transferred to the Seventh Rhode Island in August 1862. His commission was revoked by Governor William Sprague in November 1862 and he was replaced by John R. Stanhope of Newport. Linnell returned to Rhode Island and went to New York City and died in a machinery accident there in 1867. Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 329-330. Dean S. Linnell Papers, author’s collection.

[20] First Lieutenant George B. Inman was a native of Burrillville. A graduate of the State Normal School, he was a teacher when he was commissioned in September 1862 in Company H of the Seventh. Inman was assigned as the commander of the Seventh’s wagon train. He resigned shortly after the Battle of Fredericksburg. After the war he moved west and is buried at Fort Leavenworth National Cemetery. Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 361. The village of Brand’s Iron Works in Richmond, RI, is now known as Wyoming.

[21] Second Lieutenant Joseph W. Morton was born on January 3, 1821 in Lawrence County, PA. He became an educator and Seventh Day Baptist minister before the war and in 1859 moved to Hopkinton to become principal of the Hopkinton Academy. Enlisting in August 1862, he became ill with malaria and resigned in December 1862. After returning home he resumed his ministerial duties and moved to the Midwest. He died in Minnesota in 1893. Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 368-370.

[22] S.S. Griswold, Historical Sketch of the Town of Hopkinton: From 1757 to 1876 comprising a period of 119 years. (Hope Valley: L.W.A. Cole, 1877), 46-51. Gayle E. Waite and Lorraine Tarket-Arruda, Hopkinton, Rhode Island Historical Cemeteries. (Baltimore: Gateway Press, 1998), NP, entry HP #4.

[23] Gideon F. Collins, Pension File, National Archives.