The pioneering Union (Horse) Railroad Company, Rhode Island’s largest mass transit carrier, survived several competitive scares in the late 1880s. The town of Woonsocket had hosted the first regular electric streetcar service in the state in September 1887. Although the venture quickly failed, local management at the URR was embarrassed by the upstart inventiveness in this rural outpost. Two years later the Newport Street Railway overcame the outrage of wealthy summer colonists, in the City-by-the-Sea who wanted no street rivals for their expensive carriages. Regular trolley service began in August 1889 and, while not a threat to the Union Railroad at the time, the new juggernaut was far superior to horsecar travel in and around Providence. Then, as we saw in the last installment, the Cable Tramway Company provided another form of rapid transit when it initiated service over College Hill in December 1889 and threatened alter a head-to-head challenge for other’ routes.

The Union Railroad had seen enough. The carrier bought out the cable road and then got serious about electrifying the whole operation. But the managers still agonized over which technology to employ. The promise of electric propulsion opened a bewildering array of inventive opportunities in the United States. The pioneer period of electric service pitted different methods and applications against one another in lucrative races to establish accepted operational standards, not unlike the spirited competition between automobile manufacturers in the early days of that industry.

Woonsocket had hosted the first regular electric streetcar service in the state in September 1887 (Providence Public Library Digital Collections).

In the Spring of 1889 the Union Railroad petitioned the Providence city council to experiment with electric storage batteries on several city routes. The Julien Electric Traction Company, using the technology of Belgian inventors, introduced the concept of battery power in New York City. If successful, battery powered streetcars would not require poles, overhead wires and other unsightly appurtenances. Cellular energy also tempered public anxiety over potential fire hazards. The Union Railroad felt the overhead trolley method would not work well in the narrow, constricted streets of Providence so management took Mayor William Barker, city clerk Henry Joslin and the entire railroad committee to New York to witness the Belgian battery system in person. The visitors rode battery-operated street cars and inspected property on the Fourth Street and Madison Avenue Railroad. The party was impressed and the Union Railroad

felt vindicated that it had not hastily embraced the overhead wire concept.

Two special streetcars, designed by John Stephenson and Company, arrived in Providence in October 1889. Horses pulled the battery cars to the Elmwood Avenue Carbarn where the company prepared facilities to charge batteries, popularly known as “buckets of lightning.” But before trial runs began, a New York court placed an injunction against the Julien Company, halting further experiments until design and engineering litigation with a competitor was settled.

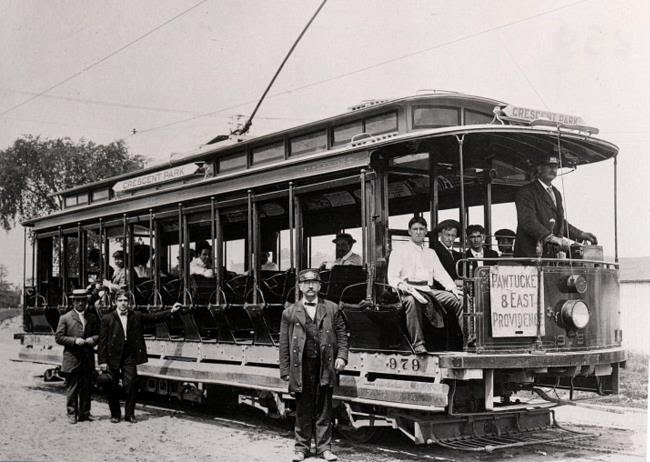

Trolley at Riverside on the line to the Amusement Park at Crescent Park, 1910 (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

The Union Railroad quickly changed for an examination of an overhead electric system employed by the West End Street Railway. In June 1890 the Union Railroad began belated experiments with battery cars after a judge lifted the Julien injunction. A promotional trip hosted Reeves’ American Band to Pawtuxet, “The band played enlivening music while passing up Westminster Street and an admiring throng watched the strange object.” But there were too many problems with battery streetcars, said Union Railroad spokesmen. Batteries required frequent and prolonged charging and were virtually inoperative on moderate inclines. Nor did management believe in the feasibility of a citywide cable operations an underground conduit system. The Union Railroad instead endorsed the overhead trolley method in use in Boston, although this meant disfiguring the city with an unsightly grid of aerial wires.

The city council held a series of entertaining hearings. The telephone company, the most vociferous opponent, wanted the Union Railroad Company to install an expensive double trolley system that might prevent electrical interference with conversations. William Roelker, counsel for the railway, bitterly ridiculed what he termed poor phone service to 4,300 subscribers in the state: “You ask that the best system of street railroads be excluded,” he scoffed, “in order that the worst system of telephone service should be allowed to exist.” Representatives of the Sprague Electric Railway and Motor Company, proponents of the overhead single trolley system, cited ongoing successful operations in 125 American cities. The Sprague interests also trumpeted a prestigious endorsement from Thomas Edison.

Open-front 1893 Jones car on Eddy Street. The car was painted ornate green and red, with the name of the line painted on the dasher and side (R. L. Wonson Collection)

Individuals, from Elmwood and Broadway, on the other hand, brought petitions against electric service. Like residents from other well-to-do neighborhoods they protested the erection of ungainly poles for electric wire support. Downtown businesses, by contrast, endorsed faster transportation.

In late July 1891 Roelker concluded his arguments in favor of the trolley to the city council with seasoned reasoning. He recalled how horsecars helped populate isolated city neighborhoods and increased property values. The electric streetcar would retire horses and eliminate dust, offal and noise from streets, he said. As to individual protests against new transportation, “They always want them put near some other fellow’s house.” Nor, he honestly observed, could the rural ideal be prolonged in a twentieth century metropolis: “People cannot live in a large modern city and have the quiet and retirement of the country.” Hearings continued sporadically for almost another year with telephone and railway interests slugging it out.

In late October 1890 the city council’s railroad committee unanimously endorsed the Union Railroad petition for general electrification. But the full council voted 23 to 13 to deny the request, ostensibly citing potential danger from an electric system, while in reality seeking financial concessions from the carrier. The council had good cause. The annual report of the railway underscored the corporation’s wealth: seventeen million passengers, a fleet of 1,515 horses and 301 horsecars, and another 8% dividend for the tenth year in a row.

The Union Railroad presented a modified petition for electrification in January 1891, proposing two specific routes for the experiment: Pawtucket and Pawtuxet, recent recipients of reduced fares by the carrier. The company’s magnanimity had been used simply to buy resident support and blunt potential antagonism to electric service in those communities. The railroad committee approved the Pawtuxet line, specifying certain safety features but emphasizing a linkage, between mass transportation and city growth. A few days later the full council began deliberations on the question. By this time discussion centered not on electricity, which was a foregone conclusion, but on compensation to the city by the Union Railroad, for such a concession. Many other companies provided free transfer tickets. Finally the full council authorized electricity on the Pawtuxet line before a packed gallery of spectators at City Hall. Before granting approval, councilmen concluded that “Providence is very much behind her sister cities in securing an adequate return for the use of the public streets.” City fathers decided to wait and see how the trolley performed before making a move for more taxes and concessions.

Needing no further encouragement, a syndicate of land speculators bought large tracts of unimproved land along the Pawtuxet line. One advertisement lauded the village as Pawtuxet-By-The-Sea, offering “Unobstructed View of the Narragansett from Squantum on the north to Rocky Point and Prudence Island on the south, while on the west the twilight splendors of the blue ribbed hills, bathed in the purple glory of the setting sun, give sweet repose.” Thirty new homes appeared by the end of the year even before the advent of electric trolley service.

By the end of 1891 the Union Railroad tested electric streetcars along Broad Street into Pawtuxet. The inaugural public trips ran smoothly on January 20, 1892, despite having to share some tracks with slower horsecars. Curiosity seekers and commuters thronged the trolleys on a day when the temperature never reached freezing. Frost On the windows interfered with any sightseeing. The motorman, who operated the trolley on a front platform with no protecting shield, was described by a reporter as being “done up to the crown of his hat in storm clothes.” A conductor, who enjoyed some warmth inside the vehicle, collected the nickel fares. As a precautionary measure, a skilled electrical engineer road the rails that day in case of unforeseen emergencies.

The rides proved smooth and uneventful. A Journal reporter noted how the trolley handled curves better than horsecars: “they were followed with the finest sort of delicacy by these cars—no creaking and no audible straining, only a silent, easy, steady movement, which was pleasant for a passenger to feel.” The electric trips to Pawtuxet “fairly roared” with power, making the journey in about twenty minutes, half the time of a horsecar. Horse-drawn sleighs promptly got out of the trolley’s way on the city’s widest thoroughfare.

One of the most popular employee perks was an annual outing from each “car-barn” to one of the state’s amusement parks for a clambake. This trolley prepares to embark from the Elmwood Avenue garage on August 18, 1909. The first person in the middle row to the far left, next to the American flag, is the author’s grandfather, Henry W. Molloy, an Irish immigrant (Scott Molloy Collection, Robert L Carothers Library (at URI), Special Collections and University Archives)

Soon afterward, the railroad commissioner reported that “Citizens who formerly opposed the establishment of electric lines have changed their views and in many cases have been among the most ardent supporters of a ‘system of traction in which they have come to recognize as the most beneficial to their property interests and the most conducive to their personal comfort and convenience.” Other interested parties were laying plans for a takeover of the local traction company by an out-of-state holding company.

[Banner Image: One of the most popular employee perks was an annual outing from each “car-barn” to one of the state’s amusement parks for a clambake. This trolley prepares to embark from the Elmwood Avenue garage on August 18, 1909. The first person in the middle row to the far left, next to the American flag, is the author’s grandfather, Henry W. Molloy, an Irish immigrant (Scott Molloy Collection, Robert L Carothers Library (at URI), Special Collections and University Archives)]