[Editor’s Note: This article is adapted from an address Patrick T. Conley gave at the Old Colony House in Newport on May 3, 1976]

I have chosen to examine an event of our state’s formative years in which the Rhode Island court system was directly involved.

Let me first observe that the revolutionary era did not end in 1776 with Rhode Island’s renunciation of allegiance, nor in 1781 with the surrender of Cornwallis, nor even in 1783 with the ratification of the Treaty of Paris. As all the leading historians have demonstrated, the revolutionary movement did not reach fruition until the establishment of a government under the present Constitution of the United States. That event for most of the original thirteen occurred with the inauguration of George Washington on April 30, 1789.

Rhode Island, however, which was first in war, was last in peace, and its period of political gestation extended to May 29, 1790 when it reluctantly ratified the handiwork of the Philadelphia Convention (in which it took no part) by the narrowest of margins and only under political and economic pressure from the new national government. The events leading to Rhode Island’s cesarean birth as a state in the new federal union included the case of Trevett v. Weeden, a landmark legal encounter in 1786 involving such essential issues as judicial independence and judicial review. (Judicial review is the power of a court to rule that a law passed by the legislature (or an act of the executive branch) is invalid as a violation of the constitution. It was not always so that the judicial branch had this power, as opposed to the legislature.)

Trevett v. Weeden is among the best known cases ever tried before an American state court. Paradoxically, it is a case that has seldom been properly understood.

Legal historians attempting to trace the origins of the doctrine of judicial review refer to several state decisions antedating John Marshall’s decision in Marbury v. Madison as evidence of the acceptance of that cardinal principle of American constitutional law by many of our early jurists. Trevett v. Weeden is usually cited in such a litany as a major precedent for judicial review, and most accounts of the case either erroneously assert that Rhode Island’s highest tribunal declared a paper money statute unconstitutional in the Trevett decision or else they are vague and inexact in their summary of the court’s action. Let us clarify the record.

The controversy emanated from the much maligned paper money law of 1786 (whose history is a story in itself). Rhode Island’s infamous paper money plan was the offspring of the state’s revolutionary debt. It was originally advanced by newly ascendant rural politicians from South County and the western hill-towns who were attempting to solve Rhode Island’s financial ills. In May 1786, the pro-paper “Country” or “Landholders” party came to power in the General Assembly and passed legislation authorizing the issuance of a hundred thousand pounds sterling of paper money ($333,000). Because the law was opposed by creditors and merchants in the port towns who set out to discredit the issue and to undermine faith in it through a palpably false propaganda campaign, the politically dominant paper money supporters attempted to defeat, coerce, or punish their opponents by passing a “Forcing Act” in June 1786 that levied a heavy fine for non-acceptance of the paper or for contributing to its depreciation. To this Forcing Act was soon added an amendment providing for trial without jury and without appeal for violators, and specifying that such trial be held before a special court convened for that purpose only.

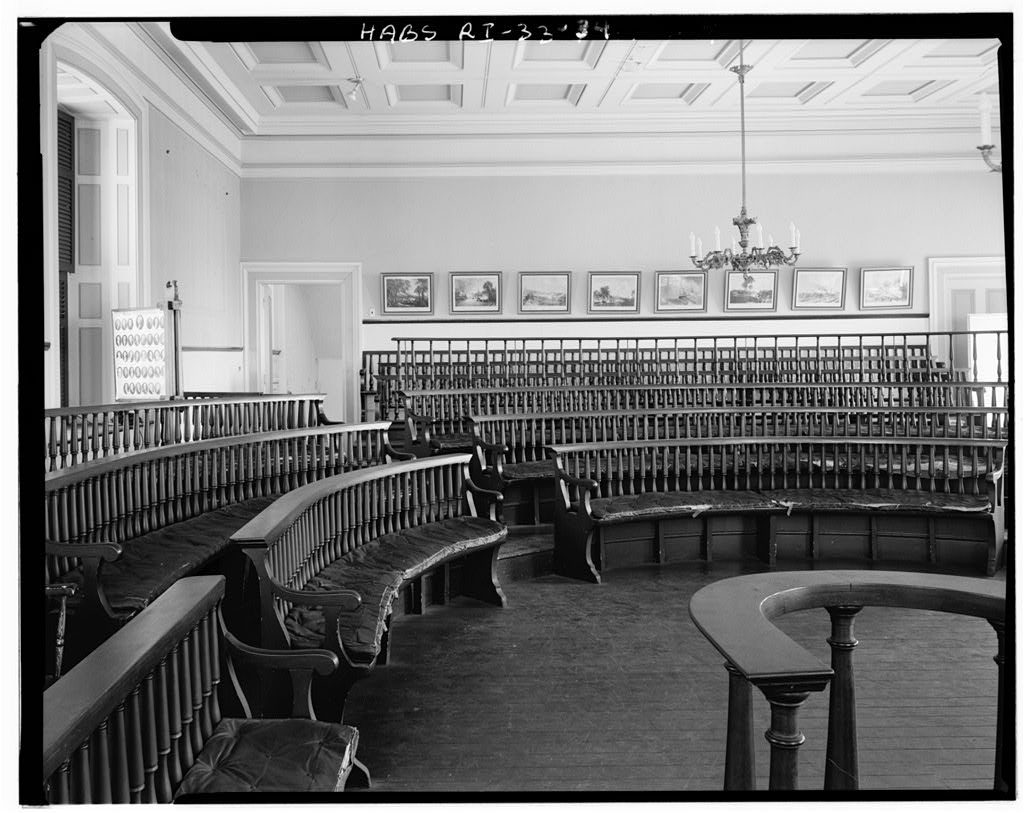

When John Weeden, a butcher who operated a shop in Newport, refused to accept a tender of paper money from John Trevett, the latter entered a complaint with the chief justice of the Superior Court of Judicature (the state’s highest tribunal) in accordance with the provisions of the Forcing Act. This precipitated the case of Trevett v. Weeden, conducted in what is called the Old Colony House (or Old State House).

Two of the state’s ablest lawyers sprang to Weeden’s defense—Henry Marchant, former attorney general and ex-delegate to the Continental Congress, and General James Mitchell Varnum, of Revolutionary War fame, and a member of Congress from Rhode Island. The trial was conducted, despite provisions of the penal law, at a special session of the Superior Court of Judicature, held in Newport on September 22, 1786, with Chief Justice Mumford presiding. The case was highlighted by Mr. Varnum’s speech for the defense, a brief which the most thorough student of the development of judicial supremacy has called one “which indicated perhaps better than any other document prior to the Federal Convention, some of the ideas on which reliance was placed in accepting the principle of judicial review of legislative enactments.”

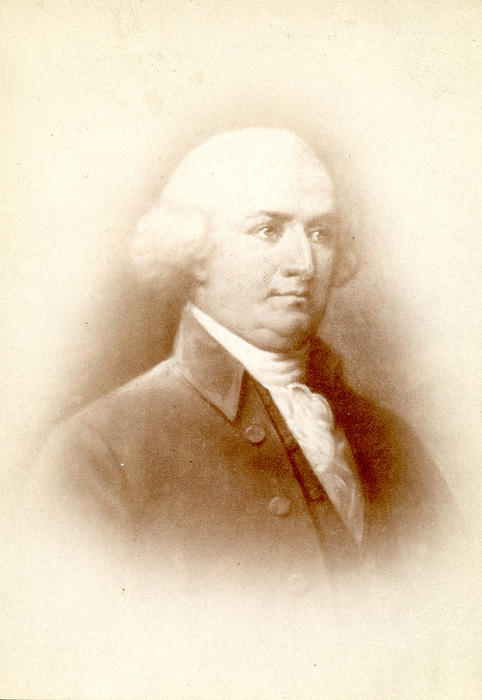

James Mitchell Varnum of East Greenwich rose to become a major general in the Continental Army, before he argued in favor of the doctrine of judicial review in Trevett versus Weeden (Independence Hall).

At the outset Varnum, a man of eloquence and imposing appearance, prayed that the court would not take cognizance of Trevett’s complaint because of three major objections to the act under which the charge was brought. First, defense counsel contended that the act under which Weeden stood accused had expired ten days after the rising of the Assembly. Faulty draftsmanship of the penal statute by the legislature gave this technical allegation much merit.

Varnum informed the judges, however, that “we do not place our principal reliance upon this objection.” He then embarked upon a more formidable avenue of attack, namely that by the statute “special trials are instituted, incontrollable by the Supreme Judiciary Court of the state.” This was a gross violation of the long-standing principle that “The highest court of law hath . . . . power to reverse erroneous judgements given by inferior courts and the duty to command, prohibit, and restrain all inferior jurisdictions, whenever they attempt to exceed their authority or refuse to exercise it for the public good.”

The final aspect of the penal act to be attacked by Varnum was its failure to provide the accused with a jury trial. His arguments on this point were most effective. He made several allusions to the charter of Charles II, then the state’s basic law, and listed two principal causes of colonial discontent on the eve of the Revolution in the process of developing his position.

Of the many famous occurrences at the Old Colony House in Newport, on Washington Square, one was the Trevett versus Weeden case (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

“Trial by jury,” asserted Varnum, “was ever esteemed a first, a fundamental, and a most essential principle in the English constitution.” This “sacred right” was transferred from England to America by numerous royal grants, including Rhode Island’s charter of 1663. The charter provision giving colonists the right to “have and enjoy all liberties and immunities of free and natural subjects” of England was then cited in proof of this contention. These privileges and immunities were abridged by the Stamp Act levy and by England’s use of admiralty jurisdiction. In fact, attempts of Parliament to deprive colonists of trial by jury “were among the principal causes that united the colonies in a defensive war,” contended the learned Revolutionary general.

Now, that long-cherished right of trial by jury was being denied by the Rhode Island General Assembly, claimed Varnum. This was a clear usurpation, for the charter prohibited the legislature from making laws “contrary and repugnant” to the general system of laws which governed the realm of England at the time of the charter grant. The Revolution, said he, had made “no change” in this limitation on legislative power. Trial by jury, he contended, “is a fundamental right, a part of our legal constitution,” and one with which the Assembly cannot tamper. The message was clear—the legislature must not deny to the people the fruits of their successful struggle for liberty!

Then, after references to Coke and other legal authorities, Varnum espoused the doctrine of judicial review in his formidable and forceful summation:

“We have attempted to show, that the act, upon which the information is founded, has expired; that by the act special jurisdictions are erected, incontrollable by the Supreme Judiciary Court of the State; and that, by the act, this court is not authorized or empowered to impanel a jury to try the facts contained in the information; that the trial by jury is a fundamental, a constitutional right— ever claimed as such—ever ratified as such—ever held most dear and sacred; that the legislature derives all its authority from the constitution—it has no power of making laws but in subordination to it—it cannot infringe or violate it [the constitution]; that therefore the act is unconstitutional and void. That this Court has power to judge and determine what acts of the General Assembly are agreeable to the constitution; and, on the contrary, that this Court is under the most solemn obligations to execute the laws of the land, and therefore cannot, will not, consider this act as a law of the land.”

Contrary to generally accepted belief, Rhode Island’s highest court did not, on the basis of Varnum’s appeal, declare the penal statute unconstitutional and void. It did, however, accede to his plea by denying jurisdiction over Trevett’s complaint, for the Court unanimously decided “that the said complaint does not come under the cognizance of the Justices here present, and . . it is hereby dismissed.”

Presumably cognizance was denied because the justices heard the case in special session of the regular term and not as a special court as directed by the Forcing Act.

In the commotion which followed the trial, knowledge of the specific decision was somehow distorted, for the infuriated Assembly in special session issued a summons requiring immediate attendance of the judges to render their reasons for adjudging “an act of the supreme legislature of this state to be unconstitutional, and so absolutely void.” This may have been the justices’ personal view, but it was not their formal decision.

The court room on the second floor of the Old Colony House in Newport, where Trevett versus Weeden was heard in 1786 (Library of Congress)]

(Unquestionably the Assembly’s misstatement is the source of the erroneous notion entertained by numerous historians which this article seeks to correct).

In early October, after a two-week delay, Judges David Howell, Joseph Hazard, and Thomas Tillinghast appeared to defend their course of action. Chief Justice Paul Mumford and Associate Justice Gilbert Devol were conveniently ill.

Both Tillinghast and Hazard, the latter a paper money supporter, stoutly defended the judgment they had rendered. Howell did likewise in a speech much lengthier and more fully preserved. He asserted that the justices were accountable only to God and their own consciences for their decision. It was beyond the power of the General Assembly to judge the propriety of the Court’s ruling, the angry Howell continued, for by such an act “the legislature would become the supreme judiciary—a perversion of power totally subversive of civil liberty.” Howell then contended for an independent judiciary so that judges would not be answerable for their opinion unless charged with criminality. In support of his position he made impressive citations from Montesquieu, Blackstone, and Bacon.

Showing little remorse or contrition for his act, Howell boldly informed the lawmakers that the legislature had assumed a fact in their summons to the judges which was not justified or warranted by the records. The plea of Weeden, he pointed out, mentions the act of the General Assembly as unconstitutional, and so void, but judgment of the Court simply is that the information is not cognizable before them. Hence it appears, chided Howell, that the plea has been mistaken for the judgment. His personal opinion, however, was that the act was indeed unconstitutional, had not the force of law, and could not be executed.

David Howell, a prominent lawyer from Providence, made effective arguments in favor of the doctrine of judicial review. Three years later he helped to found the Providence Abolition Society, becoming its president (Providence Public Library Digital Collections).

The response of the judges, especially that of Howell, did little to endear them to the General Assembly. Thus, the legislature declared its dissatisfaction with the judges’ retorts and a motion was made to dismiss them from office. Before the vote on this imprudent suggestion was taken, a memorial signed by the three judges was introduced and read. They had anticipated the plan to remove them, and they demanded as freemen and officers of the state the right of due process—“A hearing by counsel before some proper and legal tribunal, and an opportunity to answer to certain and specific charges . . . before any sentence or judgment be passed, injurious to any of their aforesaid rights and privileges.” After the memorial, General Varnum addressed the House in defense of the Court.

This determined show of resistance caused the Assembly to waver. A motion was passed directing that the opinion of the attorney general and other learned lawyers be obtained on the question of “whether constitutionally, and agreeably by law, the General Assembly could suspend, or remove from office the judges of the Supreme Judiciary Court, without a previous charge and statement of criminality, due process, trial, and conviction thereon.”

Attorney General William Channing (father of the famed Unitarian minister) and others consulted answered in the negative. Thus, it was resolved by a large majority of the legislature that “as the judges of said Superior Court are not charged with criminality in giving judgment upon the information, John Trevett against John Weeden, they are therefore discharged from any further attendance upon this Assembly on that account,” and are allowed to resume their functions.

The forcing statute which sparked the dispute was repealed in December, but the Assembly gained some measure of satisfaction from the independent-minded court when it declined to re-elect Howell, Hazard, Tillinghast, and Devol upon the expiration of their terms in May 1787. Chief Justice Mumford, who had failed to testify, either because of illness or discretion, was surprisingly retained. Congressional delegate Varnum and Attorney General Channing were also ousted because of their defiant stand, whereas Henry Goodwin, state’s counsel in the proceedings, was elevated by the Country Party to the position vacated by Channing.

As the foregoing analysis reveals, the decision of Rhode Island’s highest tribunal in Trevett v. Weeden was not an authentic or technical precedent in the development of judicial review. Nor did the action of the Court prevent implementation of the paper money program. Further, the effect of the case upon Rhode Island’s long-range judicial development was slight. Trevett v. Weeden was a cause célèbre, which produced great temporary excitement but made little permanent impact upon the operations of Rhode Island’s governmental system. After 1786 the legislature continued to exert as much control over the state’s courts as before. Judges continued to be elected annually by the dominant party—despite periodic protests of reformers—until establishment of a written state constitution in 1843. The Assembly continued to entertain petitions from individuals adversely affected by legal decisions and often honored such petitions by overturning the judgment of the Supreme Court in cases of insolvency and by authorizing new trials in civil suits. These practices were not terminated until 1856 when the state Supreme Court finally asserted its independence of the Assembly in the landmark case of Taylor v. Place. Until the Taylor decision—seventy years after Trevett—no state court dared challenge the Assembly; and no Rhode Island justice gave official endorsement to the doctrine of judicial review.

The real significance of the Trevett v. Weeden episode lies not in the formal action of the Court but in the utterances of defense counsel James Mitchell Varnum and, to a lesser degree, in the personal observations of Justice David Howell.

General Varnum’s statement of the doctrine of judicial review was one of the most forceful and extensive arguments on that subject developed during this formative period. Assuredly his position was known to the framers of the Federal Constitution and to such state supporters of that document as James Iredell and John Marshall. Varnum furnished his contemporaries and posterity with a full statement of his views by publishing them in pamphlet form together with an account of the trials of both Weeden and the judges. Varnum’s work was widely disseminated and even advertised for sale in the Philadelphia press during April and May 1787 as the delegates were entering that city to participate in the Grand Convention.

To this eloquent attorney and harbinger of judicial review and also to the courageous Justice David Howell, who defiantly asserted the independence of his court from legislative interference, our courts and our legal historians owe a duty of deference and acknowledgment.

[Banner image: The court room on the second floor of the Old Colony House in Newport, where Trevett versus Weeden was heard in 1786 (Library of Congress)]