The lighthouse for centuries has been a comforting beacon in the night. Today, these gentle sentinels are automated with sophisticated electronic illumination often powered by solar energy. They require only periodic maintenance. Yet for most of these centuries, until the mid-twentieth century, individuals, mostly men, operated and maintained the lighthouses. Light keepers cleaned and polished the lantern by day ensuring its operation in darkness and foul weather.

In colonial times, local communities built lighthouses and hired keepers often on the basis of patronage, not ability. This practice gave rise to wide variation in the quality of services. Shortly after the adoption of the U.S. Constitution, the new federal government took over the operation of the growing number of beacons. An agency of the Treasury Department managed them until the turn of the twentieth century. In 1903, light keepers became civil service employees under the Department of Commerce. There they stayed until the entire operation was turned over to the U.S. Coast Guard in 1939 where it remains today.

In 1800, there were 24 lighthouses in America. The golden age of lighthouses occurred in the nineteenth century when the number greatly increased. Still, there were never more than 1,000 lighthouses in the U.S. Today, there are fewer than 700. Fortunately, some darkened lights, slated for destruction, have been rescued and remain in service, or at least remain in existence, under private organizations.

A light keeper’s life was not for the faint of heart. It was often lonely and frequently dangerous. While the majority of tenders were men, there were a number of lady keepers. Most succeeded their husbands, but some were directly appointed.

This article focuses on one of the most famous of all the keepers: Idawalley (“Ida”) Zoradia Lewis. She succeeded her father and mother at the Lime Rock Lighthouse in Newport, Rhode Island. She became world famous for her legendary rescues of people from the harbor’s stormy waters. While her bravery and dedication earned international recognition, she remained shy and modest about her accomplishments.

During the eighteenth century Newport became a major trading center on the East Coast. The American Revolution and the British occupation took its toll on Newport. Farther up Narragansett Bay, Providence overtook Newport as an important port. But by the 1850s, the Newport was reviving. The wealthy discovered Newport as a summer getaway. Steamships brought tourists and large sailing vessels carried cargoes in and out of Narragansett Bay.

With the increase in maritime traffic in Newport Harbor, the need arose for a lighthouse. In 1853, the federal government erected a small navigational aid on Lime Rock. The light sat on a simple stone structure built on the largest of a dangerous outcropping of rocks about 220 yards from shore just east of Fort Adams.

The lighthouse was reached by boat. A little wooden shack was built to provide shelter if the keeper had to stay in bad weather. The first tender was 49-year-old Hosea Lewis, a former pilot for the Revenue Cutter Service, the predecessor of the U.S. Coast Guard.

Lewis brought his wife and family to Newport and settled across from what is today Aquidneck Park. A marker on their eighteenth-century house at 283 Spring Street denotes it as the birthplace of Ida Lewis. Hosea’s first wife had died childless, and he remarried in 1838, to Idawalley Zoradia Willey, the daughter of a Block Island physician. They had several children. Their first was a girl who died at the age of ten. Their second was also a daughter, born on February 25, 1842. Named after her mother, she would be known simply as Ida. A few years later, the Lewises had another daughter, Hattie, who remained an invalid for most of her life. Finally, two sons were born: Hosea (known as Hosey) and Thomas Rudolph (known as Rud).

By her early teens, Ida had become an accomplished oarswoman. She frequently accompanied her father, rowing their skiff across the harbor to tend Lime Rock’s lighthouse. Ida soon learned to handle a small boat expertly.

In 1857, for $1,500, the government built a small, but comfortable, hip-roofed brick house on tiny Lime Rock. On one corner a chimney-like light tower faced the harbor. In June, the Lewis family moved in. Just four months later, Hosea Lewis suffered a stroke, rendering him an invalid for the rest of his life. In the practice of the time, his wife took over his duties (although he officially remained the keeper). The now teenaged Ida assisted her mother.

At fifteen, Ida was rowing her younger siblings ashore each day so they could attend school. Ida’s school days were over. As well as skillfully handling the heavy skiff, Ida had become an accomplished swimmer, unusual in for a woman in those days. When her lifesaving experiences became known, some questioned whether it was appropriate for a young woman to engage in such activity. Ida didn’t mince words. In her plain, simple style, she said, “None, but a donkey, would consider it ‘unfeminine’ to save lives.”

Although Lime Rock lay just inside Newport Harbor, it was not immune from the vagaries of the weather. Sudden squalls are still frequent. The rocky outcroppings and shallow waters pose dangers to craft of all sizes.

After taking her younger siblings to and from shore, and handling household duties with her mother, Ida cleaned the Fresnel lens in the little three-foot square lantern room and then tended the light nightly with her mother, often sleeping in a small room next to the lantern area. Lighthouse duty was a round-the-clock job, requiring meticulous care of the lens, ensuring that the fueling and lamp wicks were maintained. (In most other lighthouses, winding the clockwork mechanisms that kept the light rotating (and fog signal operating) was necessary; but that task was not required at Lime Rock as the light showed a fixed white beacon and there was no fog signal).

Ida’s first rescue occurred in 1858 when she saved four boys whose sailboat had capsized in view of the lighthouse. The boys were from well-to-do families and students at a local private school. The quartet had taken a friend’s sailboat for a joyride that quickly turned to near tragedy. As one boy climbed the mast, his antics caused the boat to capsize, throwing all of them into the bay. Ida heard their cries for help and dashed to the lighthouse dory.

Ida was barely five-foot-four tall and weighed a little over a hundred pounds, but she deftly maneuvered her boat and pulled the boys over the stern. Back at Lime Rock Ida’s mother gave the rescued youngsters hot drinks and dried their clothes. The boys never told anyone and the story didn’t come to light until almost forty years later after Ida’s fame had spread worldwide. Ida herself never thought to mention it since to her it was just the right thing to do. One of the boys, Samuel Powell, outlived Ida and served as a pallbearer at her funeral in 1911.

In 1866, three drunk soldiers on their way back to Fort Adams hijacked a skiff to row across the harbor. Ironically, the boat happened to belong one of Ida’s brothers. Partway across, one of the men put his foot through the hull. Two of them either drowned or just took the opportunity to desert. History is silent. The third man must have cried out for help or signaled his distress. He floated with the slowly sinking rowboat until Ida came to the scene. She hauled his waterlogged body into the boat and he returned to the fort. No one thanked her.

In 1867, three men were escorting a valuable sheep belonging to the renowned wealthy banker and politician, August Belmont, when the animal jumped into the harbor. The men chased after it in the chilly, choppy waters aboard a small boat but were quickly overwhelmed. Ida, ever watchful, rescued the trio. She then returned and hauled the frightened, wet sheep into her boat. Again, little recognition came to her.

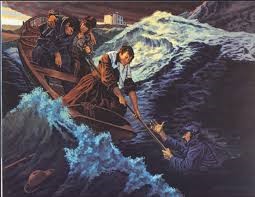

Finally, a rescue in 1869 brought Ida widespread attention. It was not uncommon for Fort Adams solders on liberty to seek an easier way back to their quarters than hoofing it from Thames Street all the way to the fort to the west. On March 28, Sergeant James Adams and Private John McLaughlin, after a night of tavern hopping, decided to go back to the fort by boat. A 14 year old boy joined them in the boat, guiding them across the harbor. A sudden snowstorm kicked up and the harbor’s waters turned turbulent. The boat capsized, tossing the boy into the water. The soldiers fell out too, but clung to the overturned skiff.

Ida’s mother saw the endangered soldiers and boy in the stormy waters. She called for her daughter. Ida had a bad cold, but that did not stop her. Failing to even put on a coat or shoes, she and her brother Hosey launched the lighthouse boat. With considerable effort, they reached the struggling soldiers and Ida managed to pull them aboard. The boy, sadly, had drowned.

On this occasion, Ida’s bravery was rewarded. One of the grateful men presented her with a gold watch. Other tributes arrived. Most touching of all to Ida, was a letter from the commanding officer of Fort Adams, Major General Henry Hunt. He expressed the thanks of his men. General Hunt added that his officers and men had taken up a collection to make her a gift. The letter came with $218, equivalent to more than $4,000 today.

This was Ida’s fifth rescue, but the first to gain major attention. Over the ensuing years Ida’s rescues brought worldwide publicity to Newport. She was pictured on the cover of the popular Harper’s Weekly magazine, wearing a scarf tied around her shoulders. Young women began to copy the style of the scarf. She started to receive awards. VIPs clamored to see her. A polka was written in her honor, and another piece of music titled, “The Ocean Waves Danced Highly,” bore her image.

American now had her own heroine to compare to the internationally famous Grace Darling in England. In 1838, Grace Darling, the daughter of the keeper of Longstone Light, spotted a steamship that was breaking up within sight of the lighthouse. The paddle steamer had run aground on the Farne Islands, off the coast of Northumberland in northeast England. Grace and her father, risking dangerous seas, rescued five survivors. The daring event earned Grace international fame. Sadly, she died of tuberculosis in 1842 at the age of 26. In the years to come, some Americans, looking for their own heroine, would call Ida “the Grace Darling of America.” Ida thought so highly of Grace she kept in her room a framed picture of Grace.

On May 5, 1869, the New York Life Saving Benevolent Society sent Ida one hundred dollars and a silver medal. She received a number of medals for her heroism over the years, often accompanied by a cash award. Never one to bask in fame, she put the awards away in a box in her room.

On July 4, 1869, the City of Newport declared the holiday Ida Lewis Day (despite its also being Independence Day). Although Ida was a member of the working class and in no way an equal of the wealthy elites of Newport, the city did the 27-year old heroine proud. More than 4,000 people lined the city’s main streets, dressed in their finery, many of the women wearing scarfs tied in the style in which Ida was pictured in the media.

The zenith of the day’s events was the presentation to Ida of a handsome lifesaving dory, valued at some $250. It had been purchased with funds raised from donors, large and small, including President Ulysses Grant. Surrounded by dignitaries, the dory boat, named Rescue, was paraded through the streets. Everyone marveled at its beauty: 14-feet long and made of cedar, black walnut and oak, it also sported plush dark red cushions and four oars made from walnut. All the fittings were polished copper. This was not the kind of working boat that Ida would use and it must have been overwhelming for her to see it. The Newport Historical Society preserves the dory, along with many of Ida’s personal items.

Ida Lewis Day was a hot and humid. The flowery speeches from dignitaries droned on. Ida had no intention of herself speaking in front of an audience. She had never done it and she never would. When it came time for her to accept the dory, Ida asked Colonel Thomas Wentworth Higginson to speak on her behalf. Higginson was a renowned Civil War officer who had led a black Union regiment in battle; he was also a famed women’s rights activist, abolitionist, and former Unitarian minister. After the war, he had made Newport his home. Higginson said in part:

I am requested by Miss Lewis to return thanks in her name to the donors, and to the citizens of Newport. Miss Lewis desires me to say that she has never made a speech in her life and she doesn’t expect to begin now. She receives the boat with pleasure not alone as an earnest representation of the good feeling of her fellow citizens, but also as a means of doing a little more hereafter, if the occasion should come…. [I]f any of you should be so unfortunate as to get into difficulty in the neighborhood of Lime Rock, so long as you can see this boat riding at anchor there, it will say to you as boys sometimes say to a playmate who has fallen, “come here and I will pick you up.” Miss Lewis is grateful to you for your acknowledgement of what seemed to her a simple act of duty; and she is more grateful to Divine Providence which enabled her to do what she hopes never to have to do again.

Mercifully, around 3 p.m., Ida finally was able to step into her new dory, dressed in a black gown for the occasion. With cannon saluting her, she rowed back across the harbor to Lime Rock.

Once on her small island, Ida quickly realized she had no place to shelter her new boat. Steamship magnate and financial speculator, Jim Fisk, donated the cost of a small boathouse. Fisk also presented her with a pair of expensive oarlocks, which went into a box with Ida’s other treasured possessions that were too nice to be used.

That summer, Ida’s father recorded the amazing number of between 9,000 and 10,000 people who arrived by boat to visit her. They ranged from the rich and famous to everyday people. Among them were politicians, New York City social elites along the lines of the Vanderbilts, suffragettes Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, generals, admirals, and even, while visiting Newport, President Ulysses S. Grant. Tributes and gifts poured in, along with numerous offers of marriage. But Ida’s first commitment was always tending the lighthouse at Lime Rock.

While President Grant arguably was Ida’s most prestigious visitor, he did not actually set foot on Lime Rock. When he came to Newport, his schedule was very crowded. Still, he insisted on meeting Ida. He was reputedly warned that he might get wet if he visited Lime Rock. Grant was said to reply, “I’d get wet up to my armpits to meet Ida Lewis.” He didn’t have to. Ida came to him.

Dutifully, Ida boarded her beautiful dory Rescue and rowed across to Long Wharf, where she met both the president and his wife, Julia Grant. Ida rarely used the ornate “Rescue” and preferred her old reliable dory, named Courageous Child of Columbia, which hung on the davits at the lighthouse. But, she must have figured, the president would want to look at Rescue. Witnesses said the meeting was brief, but sincere. Grant said to her, “I am happy to meet you, Miss Lewis, as one of the heroic, noble women of the age.”

That same summer, Vice President Schuyler Colfax paid a surprise visit. His cousin, Harriet Colfax, was the keeper of the Michigan City Light in Indiana. The vice-president and Ida had a pleasant conversation. Oddly, as he was leaving, Colfax asked Ida if she was engaged. His point was that if she married, she would lose her maiden name and likely her fame. Ida retorted that if she did marry she would take her husband’s name and forget her fame.

As it happens, she had been quietly engaged about three years. Shortly after the Civil War, Ida had met a Connecticut yacht captain, William Heard Wilson, when his boat called at Newport. Wilson became smitten with the local light keeper and pressed his courtship; Ida obliged. They were married on October 23, 1870, in Newport. Ida moved to Black Rock, Connecticut, a busy village on the shore of Long Island Sound. William was off at sea much of the time. Ida spent her days alone looking wistfully at nearby Fayerweather lighthouse and thinking of Lime Rock.

Ida was miserable. After barely two years, she returned to Lime Rock Light, never to have another residence. She had become a devout Christian and, consistent with her views, never divorced William. But she returned to her maiden name (although she kept Wilson as her middle name). She never spoke publicly of her husband again. Perhaps another reason that prompted Ida’s return was the death of her invalid father on November 17, 1872. He was 68 years old.

Ida diligently took up her duties. Visitors arrived, mostly to meet a celebrity. She was ever courteous, even to strangers who, not infrequently, swiped little artifacts and memorabilia from Ida’s home.

In 1877, Ida saved three soldiers whose boat had run on the rocks between the light and Fort Adams. This time, Ida became quite ill after the rescue. It took several months of rest before she regained her strength.

Ida began both caring for her ailing sister and assisting her mother more in her duties.. Her mother was being paid to tend the lighthouse, although she was never formally appointed. As her mother’s health steadily declined, Ida began to assume more and more of her mother’s duties, eventually taking on all of them. The elder Ida died of cancer the following year, in 1878. In 1878, her younger brother Hosey, married and spent the rest of his life as a teamster in Newport.

Although not one to complain, Ida was likely offended that she was not officially recognized as the keeper of the Lime Rock Light after her mother’s death. The government let things ride, simply paying Ida for her work.

The news media took note that the government had not formally recognized Ida as keeper. U.S. Senator Ambrose Burnside finally helped secure Ida’s formal appointment, effective January 21, 1879. She was awarded an annual salary of $750, making her the nation’s highest paid keeper.

Ida’s tally of rescues had quietly continued to mount. But it was an event on the ice-covered waters of Newport Harbor on February 4, 1881, that again returned her to the public’s attention.

Two drunken Fort Adams soldiers taking a short cut across the ice-covered harbor hit a thin patch and the ice gave way. Once again, without a warm coat, Ida grabbed a length of rope and tore out of the lighthouse’s door. On her way out, she called to her brother Rud to help her. The panic-stricken men in the icy waters, now practically frozen, dragged Ida into the water. Fully dressed in the cumbersome clothing of the day, Ida, with the help of her brother Rud, managed to drag the men to safety.

This time Ida was awarded a Congressional Gold Medal for Life Saving. Earlier she had been made an honorary member of the Sorosis Society, a prominent professional women’s organization, and she proudly wore its pin daily. Ida received a gold medal from the Humane Society of Massachusetts. It had never before been given to anyone outside the Commonwealth. All her awards remained out of sight, which is the way Ida herself preferred to be, as she grew older.

For the last three decades of her life, Ida stayed out of the public eye. Now and then there would be a news article about her. A devout Christian, she could often be found sitting outside the light station reading her Bible. She welcomed friends to visit her, including Elsie Vanderbilt, the young wife of Alfred Vanderbilt. She and Ida would remain friends until Ida’s death. Their friendship was unusual in those days, when the ultra-rich elites typically maintained a significant distance from average persons.

Ida lost sister Hattie in 1883 and her brother Hosey a year later. That left only her brother Rud and Ida’s ever present pet dog. She always had a dog by her side, usually a spaniel. She kept faithfully to her duties, but the changing times were catching up to her. In the early years of the new century, in her early 60s, she accomplished the final documented rescues that would bring her number to 18 (although the real number was probably closer to 25; Ida never kept count).

Lighthouse keepers (also knowns as light keepers) had always been self-sufficient and the government paid them limited attention. There was little government oversight or regulations to follow. But when light keepers became civil service employees in 1896 under the Department of Commerce, clerks hundreds of miles from her started questioning their work.

Fortunately for Ida, she had friends in high places. One was Admiral George Dewey, the hero of Manila Bay. She had named one of her beloved cocker spaniels Dewey in his honor. Another was philanthropist Andrew Carnegie, who had established a lifesaving award in 1904. Ida was not eligible since her greatest rescues had taken place before then. However, Carnegie was so impressed with her that he personally set up a stipend for her life of thirty dollars a month to help Ida in her retirement.

At age 68, Ida was slowing down. At one point, she received what she felt to be a particularly insulting letter from a bureaucrat in Washington, D.C. to which she replied but never got a response. Things would get worse. Among the many changes in the lighthouse service was the growing number of lighthouses being automated, thus precluding the need for a keeper. Ida grew worried that this would be her fate.

On the morning of October 21, 1911, Ida put out the lantern in the little tower room at Lime Rock for the final time. As she made breakfast, Ida suffered a massive stroke. She fell into a coma and never awoke. She died quietly at her beloved Lime Rock three days later at the age of 69. That night, every ship in Newport Harbor, including the mighty Fall River Line Steamer Priscilla, tolled their bells in mourning.

The City of Newport gave her a final, fitting tribute. Her body was brought ashore and taken to the Methodist Episcopal Church where she had faithfully worshipped. The Newport Daily News reported nearly 1,500 mourners paid their final respects. Simple folk were joined by the prominent. Carriages lined the streets around the church. Soldiers from Fort Adams served as her pallbearers, joined by Samuel Putnam, whom Ida had rescued as a boy long ago. The Newport Daily News made a point of blaming the government for contributing to Ida’s passing.

Members of the Coast Guard from the buoy tender Ida Lewis maintain her grave at Common Burying Ground in Newport (U.S. Coast Guard)

Ida was laid to rest in the nearby Common Burying-Ground cemetery, next to her family members. Her tombstone reads simply: “Ida Lewis…The Grace Darling of America…Keeper of Lime Rock Light. Newport Harbor…Born February 25, 1842. Died October 24, 1911. Erected by her many kind friends.”

Rud notified the Bureau of Lighthouses of Ida’s death. In typical fashion of the day, he was told to keep things going and a new keeper would arrive shortly. When the new man arrived, Rud handed over the keys and went to live with friends in Newport where he died in 1917. In recognition of his many services at the lighthouse, Ida’s pension from Andrew Carnegie was transferred to him.

Almost immediately, there began an effort to rename Lime Rock and its light in memory of Ida. In 1924 the state government finally relented. A resolution was passed by the Rhode Island General Assembly to that effect. Lime Rock officially became Ida Lewis Rock and the lighthouse Ida Lewis Light. The federal government’s marine charts were revised to reflect the change. However, in 1927, as Ida had feared, the light at Lime Rock was extinguished and replaced by an automated lantern atop a skeleton tower and the light keeper lost his post. The automated lantern remained until 1963.

In the mid-1920s, a group of prominent Newporters purchased Lime Rock and the light station for $7,200. In 1928, the Ida Lewis Yacht Club was established. Club members connected the rock to the mainland with a walkway. Clearly visible atop the Club flagpole is a triangular flag that carries 18 stars, each representing a documented life saved by Ida Lewis during her 60 plus years at the light station. The lantern that Ida lovingly tended is in a place of honor inside the club. Members have been granted permission by the Coast Guard to illuminate a small lantern in the tower in Ida’s honor between May and October.

In 1995, the U.S. Coast Guard commissioned the Ida Lewis, first of a new class of buoy tenders. The vessel’s Newport-based crew maintains her gravesite. In 2018, in another special recognition, Ida Lewis became the first woman to have a roadway at Arlington National Cemetery named in her honor.

Shy and unassuming, Ida Lewis was thrust into a spotlight that she never sought or enjoyed. She willingly maintained the harsh life of a light keeper. Over the years there have been other lady light keepers who braved the elements and even rescued those in danger, but there has never been another quite like the Heroine of Lime Rock Light, Idawalley Zoradia Lewis.

This small ceremonial lantern in the Ida Lewis Yacht Club on Lime Rock in Newport Harbor hangs in the lantern room from May through October as a memorial to Ida Lewis. The Fresnel lens lantern hung there when the lighthouse was active (Brian Wallin)

The author wishes to thank the Newport Historical Society and the Ida Lewis Yacht Club for their assistance in preparation of this story.

[Banner image: Ida Lewis rescues two drowning soldiers from Fort Adams in Newport Harbor (Harper’s Weekly, 1869)]

Bibliography

D’Etremont, Jeremy. The Lighthouse Handbook: New England. 3rd Edition. Kennebunkport, ME: Cider Mill Press, 2016.

D’Etremont, Jeremy. The Lighthouses of Rhode Island. Lighthouse Treasury Series. Beverly, MA: Commonwealth Editions, 2006.

De Wire, Elinor. Guardians of the Lights: Stories of U.S. Lighthouse Keepers. Sarasota, FL: Pineapple Press, 1995.

Gleason, Sarah C. Kindly Lights: A History of the Lighthouses of Southern New England. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1991.

Ida Lewis Yacht Club website, Our History. At www.ilyc.org/history.

Richmond, Arthur P. Lighthouses and Lightships of Rhode Island. Past & Present. Atglen, PA: Schliffer Publishing, Ltd., 2014.

Skomal, Lenore. The Lighthouse Keeper’s Daughter. Guilford, CT: Globe Pequot Press, 2010. (NOTE: An earlier edition of this book was published by the same author under the title The Keeper of Lime Rock in 2002).

Snow, Edward Rowe. The Lighthouses of New England. Updated edition edited by Jeremy D’Etremont. Beverly, MA: Commonwealth Editions, 2004.