Early ministers in Rhode Island, traveling from place to place to preach, often spoke out against various vices. For example, in his 1754 journal, the Reverend Jacob Bailey of Massachusetts assailed Providence residents for their “immoral, licentious, and profane” behavior, as well as for their contempt of the Sabbath. “Gaming, gunning, horse-racing and the like, are as common on that day as on any other,” Bailey complained.

While ministers spoke out against sundry vices, the unrepentant sinners who were the target of their sermons laughed them off and seldom responded to their insults with violence. Matters changed, however, when the “missionaries” who were sent around New England began to espouse the evils of drinking alcohol.

Alcoholism had been a concern in the early colonies from the time the first alehouses opened their doors. Despite harsh remonstrance’s from the pulpit, the severe punishments and public humiliation doled out by authorities, and the effect such drinking had upon home and family, public drunkenness and alcoholism seemed to be rampant in New England throughout the eighteenth century and into the nineteenth century.

In his 1784 pamphlet, “An Inquiry into the Effects of Spirituous Liquors on the Human Mind and Body,” Philadelphia’s Dr. Benjamin Rush was the first to undertake a serious scientific study of the physical, mental, and social effects of alcohol. But it was left mostly for clergymen to persuade their flocks of the benefits of abstinence.

Asa Niles was an established businessman in Boston when he was converted in church one Sunday. Soon afterwards, he abandoned his business for spiritual pursuits, moving to Beverly, Massachusetts, to be mentored by “Father William,” a well-known theologian who also had kept other students at the time. When his studies were finished in 1805, Reverend Niles was sent into Rhode Island as a missionary, preaching in Pawtucket, and then moving on to Pawtuxet, East Greenwich, and Centerville. Oliver Payson Fuller’s History of Warwick records that:

He was an earnest, pointed preacher, and the truths that he uttered awakened much opposition among “the lesser sort,” some of whom in the villages of Pawtuxet and East Greenwich threatened him with personal violence. At one time, while he was preaching, one of this class threw a stone at him through a window, which passed by his head, striking a woman and breaking her arm…. At another time they took his horse, on which he rode to his appointments, and sheared his mane and tail, but it does not appear that he preached any less faithfully on account of these persecutions. In fact, Niles accumulated such a following, that a church was formed; it met at times in the Court House, but also in nearby taverns and a school house.[1]

In time, other Protestant churches, particularly Quakers and Anti-Sabbatarians, took up the banner of temperance, stirring the populace of Rhode Island towns during the 1820s and 1830s.

Between 1827 and 1828, a temperance society was formed in nearly every village in Kent County. One of the principal leaders of the movement during this time was Reverend James Burlingame of the Rice City Church. Little surprise then that the McGregor Tavern, one of the longstanding alehouses in Coventry, became a temperance tavern around this time.[2] In preaching against the evils of alcohol and leading rallies to ban the sale of liquor, Burlingame often placed himself in great physical danger, at times having stones thrown at him, or having his sermons interrupted by angry villagers. His tenacious efforts were rewarded in 1827, when the prominent First Baptist Church in Providence held the first temperance meeting in the state’s capital city.

The first temperance tavern in Kent County was likely Daniel Updike’s Inn, a well-known hostelry that had been operated by the Arnold family for several generations on the Post Road in East Greenwich. Updike had married Colonel William Arnold’s daughter, Ardeliza, and had renamed the inn shortly after taking over management of its affairs. Updike, a descendant of the famous Updikes of North Kingstown, prided himself on being a family man, and became a staunch temperance supporter. In the thirty years that he operated the tavern, not a drop of liquor was served in it. Despite his stance, the inn’s rooms were nearly always full, especially during the annual (sometimes more frequent) meetings of Rhode Island’s General Assembly, and the quarterly meetings of the Society of Friends as they gathered from throughout the state.

Updike’s family heritage lent itself to some eccentricity, for he “met his guests at the door attired in old fashioned dress. He wore knee-breeches, a fancy waistcoat, and white-topped boots. His hair was tied in a queue.” The inn became famous for its colonial fare, including baked beans with brown bread baked in a cabbage leaf, Indian pudding, and calf’s-head soup.[3]

Still the temperance movement struggled to make headway with government institutions, both at the state and local levels. Mill owners had begun to support temperance in order to promote worker safety and productivity, but reaction to their measures to restrain workers from drinking sometimes met with violence. The December 31, 1843, murder of Amasa Sprague of Cranston was thought to have been due to his opposition to renewing a liquor license at a tavern near his textile mills often frequented by his workers.

It was not until doctors and educators who followed Benjamin Rush’s example and spoke out publicly against the effects of alcohol that the movement began to gain momentum. One such physician was Dr. Charles Jewett. After settling in East Greenwich in 1829, the doctor soon gained a solid reputation for his medical skills and patient manner. Sometime during his tenure as a physician in the town, he began to speak out against the use of alcohol, and his lectures proved to be well received, so much so, that, in 1837, he closed his physician’s office and became leader of the Rhode Island Temperance Society. Jewett became known as “the temperance lecturer.” In 1872, he published his memoirs, entitled Forty Years Fight with the Drink Demon, which included graphic accounts of the violence wrought upon early temperance reformers.[4]

Through the efforts of Jewett and others, the Rhode Island General Assembly enacted an Act of Prohibition in 1852. But a violent backlash arose against this law and those who had pushed to have it passed. In 1854, in the village of Apponaug, a gunpowder keg was placed in the barn of William Harrison, a well-known prohibitionist. When it detonated, the barn was destroyed, although fortunately no people were injured. The attack so incensed the town that the Warwick City Council posted a reward of $200 for the capture and conviction of the perpetrators, but no one was ever arrested.

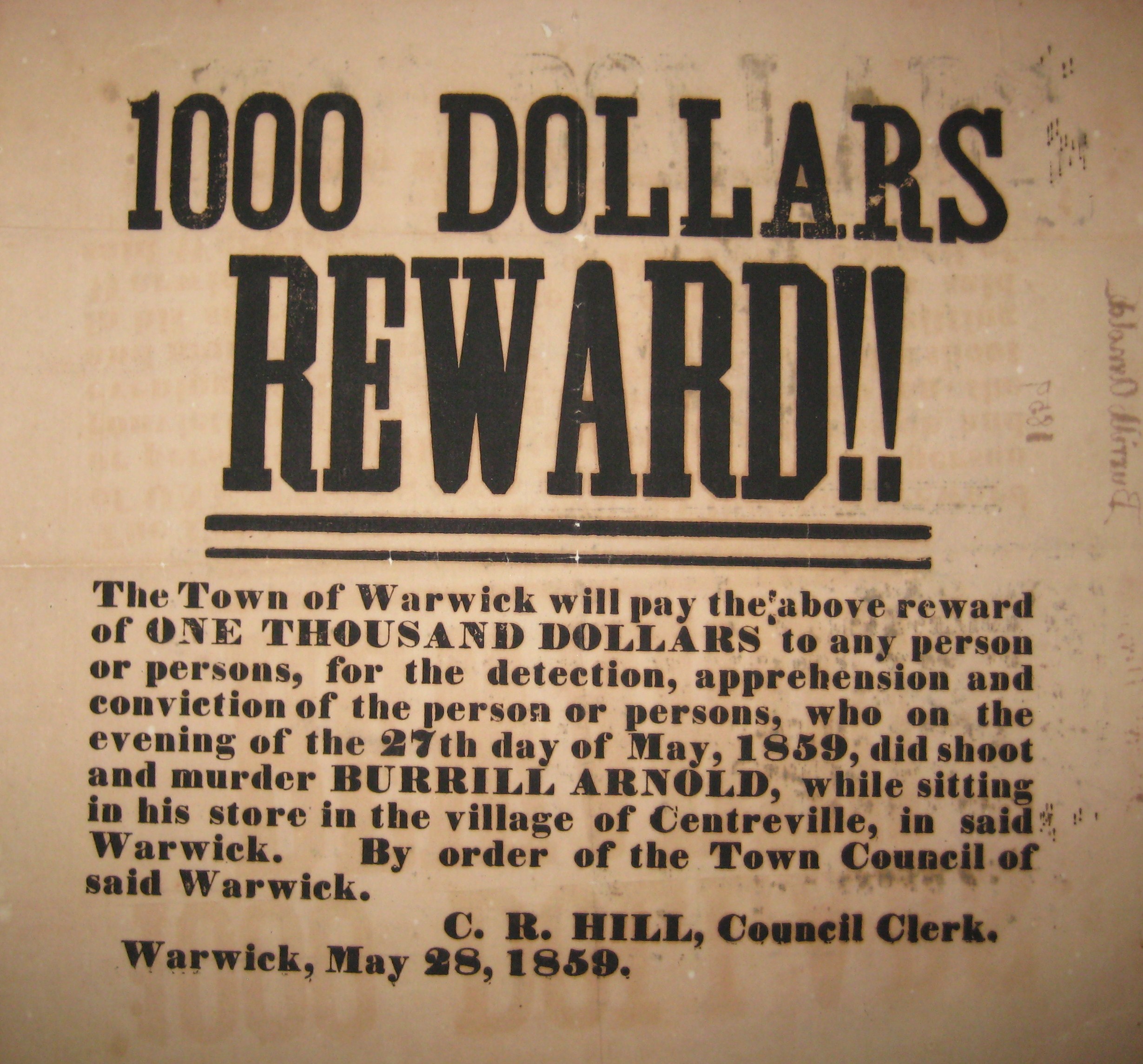

On May 27, 1859, an attack was made upon Burrill Arnold of Centerville. A prominent businessman and an outspoken supporter of prohibition, Arnold had arrived home from Providence by carriage and was sitting in his store chatting with a neighbor when a shot was fired through the store’s window, mortally wounding him.

The law prohibiting the sale of liquor was repealed in 1863 during the throes of the Civil War. It was thought that every means possible to defeat the South was needed, and prohibition was a distraction.

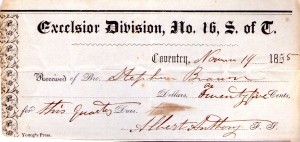

In the years following the war, the prohibition movement was revitalized and saw the establishment of numerous temperance organizations, including the Independent Order of Good Templars, the Rhode Island Temperance Union, the Rhode Island Anti-Saloon League, The Rhode Island Prohibition Party, and a Rhode Island branch of the Women’s Christian Temperance Movement. Not every temperance society thrived. In his history of the village of Greene, Rhode Island, Dr. Squire. G. Wood wrote about another temperance society that in the 1860s had a lively, but short-lived history. This was the “Independent Order of Good Templars,” which was organized at the Hopkins Hollow Church, with Mr. W.V. Philips serving as Chief Templar. According to Wood, despite the best of intentions, within a year, “dissension and lack of interest closed the charter.”[5] Other organizations were successful in their communities, and by the 1880s, they were successful in pressuring politicians. But for a while some wily politicians managed either to ignore reform efforts or found ways of working around the laws that were enacted.

In Warwick, the City Council was controlled by two men, Webster Knight and Charles R. (“Boss”) Brayton, who were renowned for the illegal activity they endorsed. Knight, the “autocrat” of the City Council, was a member of the family who owned the famous and successful manufacturing firm of B. B. & R. Knight Company. Brayton had served as a colonel in the Civil War, and had been appointed Post Master in Port Royal, South Carolina, a city he had helped to capture, before returning to Warwick and being appointed Town Clerk, a position once held by his father. By 1874, he had been appointed postmaster of Providence, and was a Republican lobbyist in the State House.

In 1886, when the General Assembly passed a constitutional amendment that prohibited the sale of liquor in Rhode Island, the two bosses made sure the law was unenforceable. Brayton helped to create the new Warwick city office of Chief of Police and maneuvered to be appointed as the initial holder of the office. Additionally, he and Knight appointed two police officers to oversee “enforcement” of the law.

The result was that while raids were conducted on liquor-serving establishments whose owners opposed Brayton’s political machine, others were ignored or given advance warning. In a report published after Brayton’s resignation as Chief of Police, the Pawtuxet Valley Gleaner explained how the prohibition law was “enforced:”

…special officers would go to the most notorious areas of Warwick, raid one establishment there, where the owner was known to be against Brayton’s “machine” and then stand on a corner where they would be conspicuous. After a while, they would slowly walk down the street and investigate establishments under complaint.[6]

Those who supported temperance believed that Knight was complicit with Brayton in these actions, and in the next election, a coalition of the newly formed Citizens Party swept the City Council president and other City Council Members from office. The new City Council took action for reforms, and for a time, the sale of liquor was even prohibited at the entertainment venue at Rocky Point. By 1888, however, the State had decided that prohibition was too costly to enforce, and the anti-alcohol act was once again repealed. In its place, a law was passed that authorized each incorporated town or village to determine if it would be “wet” or “dry.”

The General Assembly’s action, leaving each village and town with the choice of whether or not to allow the sale of liquor, largely ended the violence that ensued when prohibition supporters rallied outside of neighborhood bars. Most Rhode Island towns allowed liquor-serving taverns and saloons, but imposed their own ordinances on the hours the establishments could be opened and closed, and the penalties for violations, including excessive drinking. Local churches as well, began to focus on families within their congregations, organizing family picnics on Sunday afternoons and establishing campgrounds from the shore along Cole Farm to Warwick Downs.

Nationally, the fight for prohibition continued, eventually leading in 1919 to the passage by the U.S. Congress of the Volstead Act, which banned the sale of liquor nationwide in 1920. Both houses of the Rhode Island General Assembly voted against adopting the law, and Providence remained well known as an “open town.”[7] As historian William McLoughlin noted, “Rhode Islanders fought bitterly against the Prohibition amendment in 1918 and ours was one of two states in the Union that never ratified it.”[8] But enough states did ratify the amendment for it to become law. Rhode Island, with its many harbors and coves, was to become one of the key places for gangsters to smuggle illegal spirits into the country during the period of prohibition, as will be described in Part II of this article.

(Banner Image: Reward posted for information leading to the arrest of the murderer of Burrill Arnold (Russell J. DeSimone Collection))

[1] Oliver Payson Fuller, TheHistory of Warwick, Rhode Island (Providence, RI: Angel, Burlingame & Co., 1875), p. 323. [2] The tavern was opened by Colonel John McGregor in 1783. It became a temperance tavern in 1831. See Robert A. Geake, Historic Taverns of Rhode Island (Charleston, S.C.: The History Press, 2012), p. 23. [3] Donald D’Amato, Warwick: A City at the Crossroads (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Press, 2001), pp. 92-93. [4] Martha P. McPartland, The History of East Greenwich, Rhode Island 1677-1960 (East Greenwich, RI: East Greenwich Free Library Association, 1960), pp. 192-193. [5] Fuller, History of Warwick, p. 195. [6] Squire G. Wood, A History of Greene and Vicinity 1845-1929 (Providence, RI: Privately Printed, 1936), p.47. [7] D’Amato, Warwick, A City at the Crossroads, pp. 92-93. [8] William G. McLoughlin, “Ten Turning Points in Rhode Island History,” Rhode Island History, vol. 45, no. 2 (May 1986), p. 42.