Before 1830, travelers from Boston to New York rode by stagecoach down the old Post Road, or sailed around stormy Cape Cod, down along the unpredictable waters of Point Judith and Watch Hill, and into the more tranquil Long Island Sound. Maybe they would make it. Maybe not.

By 1835, railroads from Boston reached Providence and in 1847 extended to Stonington, Connecticut. From there, steamships carried travelers on to New York. In 1870, a railroad bridge spanned the Connecticut River at Old Saybrook. In 1889, a bridge was built across the Thames River at New London. Finally, there was an unbroken rail line between Boston and New York: the New York, Providence and Boston Railroad.

The 19th century and the Industrial Age brought significant changes across Rhode Island. Textile mills and manufacturing quickly grew the economy. Providence emerged as a commercial hub. Meanwhile, the state’s shoreline had begun to attract wealthy summer visitors from New York, Philadelphia and as far west as St. Louis, all eager to escape the ugly side of industrialization. They built ornate summer cottages (we would call them mansions) in Newport, as well as smaller ones on nearby Conanicut Island and Narragansett.

Reaching those summer island retreats required an inconvenient trip by rail and/or sea. A private railcar could be linked to trains into Providence. But the trip to Newport required a further journey aboard crowded steamboats down Narragansett Bay or continuing by rail to Fall River and connecting with the Old Colony Railroad, which led into Newport. (The Old Colony also ran a train from Boston that connected with the Fall River Line Steamships right up until 1937.) Another possibility was to take the train to Kingston, followed by a horse-drawn coach to South Ferry in Narragansett, a ferry to Jamestown, and another ferry to Newport. For passengers, this was all very inconvenient, if not downright annoying.

A group of well to do New Yorkers decided to make things easier. Their solution was to establish the Newport and Wickford Railroad and Steamboat Company (the N&W or the Newport and Wickford), which constructed and operated a rail line a mere three-and-a half miles long. The track ran from the mainline New York, Providence & Boston stop at Wickford Junction to the port of Wickford, where a company-owned steamboat could bring passengers across to Newport. The N&W began service in 1871, the start of the Gilded Age, and managed to provide combined rail and steamship service until 1925.

By 1844, there was already a mainline depot at Wickford. It was originally known as Huling’s Crossing, after one of the local landowners whose property abutted the rail line. It was the closest port to Wickford village. Arriving or departing passengers were served by a stage coach line operated by local livery stable owner William Congdon. He ran the service for about 17 years.

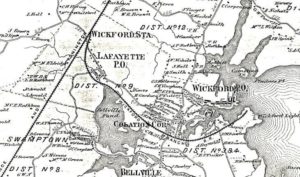

Map showing the route of N&W’s Wickford Branch railroad line, ending south of Wickford at what is now Steamship Avenue (Google sites/rhode island railroads)

For some time, there had been support for a better connection to Newport. A state charter for a rail service from Wickford up to the main line had been granted in 1864. Newporters used that document to push for a steamship connection direct from Wickford. It took them four years, but in 1869, Newport voters voted by a two-to-one margin to support such a venture.

Almost immediately, several well-heeled New Yorkers got together to put up the capital for the venture. Cornelius Vanderbilt II and his brother Frederick, no strangers to rail transportation, formed the Newport and Wickford Railroad and Steamboat Company with several other investors. As president, they elected George Miller, a frequent summer guest of John Carter Brown in Newport. Other members of the board included political figures like Senator George Peabody Wetmore and Congressman George Gordon King.

Newport and Wickford Railroad Forney locomotive #1, along with an Osgood Bradley passenger car (G.T. Cranston collection)

These were men who knew how to make things happen. The ink was barely dry on the Newport endorsement when construction on an already laid out right of way began in March of 1870. With an almost level right of way, construction could be quickly completed. There were only four roads to cross, all at grade level, so no expensive bridges were required.

On June 1, 1871, some five years ahead of the Narragansett Pier Railroad between Kingston and the Narragansett shoreline, the little N&W was open for business. One month later, steamboat service began from Wickford Landing to Newport’s Commercial Street wharf. On its first run, the N&W’s steamboat Eolus carried 140 passengers.

Eolus was the first established steamer used by the N&W on journeys across the bay between Wickford and Newport. Built in 1864 in placed in service by the Union Navy, it captured a Confederate blockade runner during the Civil War (Naval History and Heritage Command)

The Wickford Junction station was situated beside Ten Rod Road roughly opposite to what is now the Wickford Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) station. Until 1938, when the mainline overpass was built, this was a grade level crossing.

The original depot was completed in 1844, rebuilt in 1871 to accommodate the N&W, and further expanded in 1887 with a shelter for the branch line itself. The station went through another iteration following a 1914 fire.

After the N&W ceased passenger operations in 1925, the depot continued in use until it was razed in 1969. A pedestrian overpass to the southbound tracks was moved to the Route 128 station in Massachusetts two years later. The last Amtrak train stopped at Wickford on October 1, 1981, ending over one hundred years of passenger service. Today, a new Wickford station serves the MBTA commuter line to Boston.

At the junction, there was a water tank and a manually operated turntable. There was a similar device at the Wickford Landing pier. These were sometimes jokingly called “Armstrongs” as it took the power of several strong men to start the well-greased table in motion and turn the locomotive around.

The short line became a boon to the neighboring villages of Lafayette and Belleville. The railroad generated business from travelers for restaurants and shops, and even a hotel sprang up in Lafayette. Similar ventures opened in Wickford Village. Wickford Junction Station was ably supported by carriage services and freight delivery that extended in all directions.

Travelers were soon arriving from as far away as Chicago and St. Louis. The private rail cars of the wealthy New Yorkers were backed onto the siding where the N&W’s sole locomotive patiently waited to haul them to Wickford Harbor.

For those without a private Pullman parlor car, the mainline railroad added a “Newport Car” reserved for passengers also heading to the City by the Sea. This car was also just shunted into the N&W tracks. Whenever demand increased, so did the number of cars.

From the junction, the N&W ran in a gentle, level curve through the villages of Lafayette and Belleville. It passed over a little bridge at Shewatuck Brook below the Rodman Mill Pond, where for generations, the Rodman family had a major impact on the economic and social life of Lafayette. The railroad built another water tank there, taking advantage of the nearby pond. A siding to serve the mill’s needs was also added. In later years, a small shelter protected passengers.

The right of way, visible today on satellite maps, passed through the woods until it reached the site of the present State Transportation Department Garage on Tower Hill Road, about two miles from the start of the rail line. Here stood Belleville Station, completed in 1871 in time for the opening of the N&W. The location was also convenient to the nearby Belleville textile mill.

Belleville Station handled freight and passenger service and was also a post office. There was another spring-fed water tank just south of the station and its freight siding. The station remained in its original location until passenger service ended, after which it was moved across the road next to St. Bernard Church.

One might say Belleville Station also had a higher purpose. The growing Catholic population of North Kingstown, mostly Irish and French-Canadian millworkers, was being served by priests from Our Lady of Mercy parish in East Greenwich who would travel south to North Kingstown and say Mass in private homes. By 1874, the Catholic population had grown to the point where St. Bernard Church was built across from the railroad station.

A remnant of Belleville Station still exists as part of local hardware store and lumber yard, although one has to look hard to see it. The present store was constructed around the original station and an outline of the old depot can be identified on the cement floor. When the N&W ceased passenger operations, the station was moved across Tower Hill Road and became the office of the Baker Coal Company. The company also used the railroad siding. When the coal company went out of business, the little station lived on. It became home to a progression of lumber yards. The hardware store initially took the name Wickford Branch since it was located adjacent to the original rail line.

From Belleville, the tracks ran another mile or so through a wooded area and over upper Wickford cove on a trestle that still remains along with rail ties that run back a distance into the woods. This was the only place along the right of way where a substantial bridge was needed. The track crossed Prospect Avenue and reached the Wickford Village Depot. The depot was shared with the Seaview Railroad trolley line. Between 1899 and 1920, the Seaview ran between Narragansett Pier and East Greenwich where it connected with service to the metropolitan area.

The Wickford Village Depot was located diagonally across from the old Town Hall, near the present Memorial Park. The topography has significantly changed, and all traces of railroad here have vanished. The N&W tracks survived the 1938 hurricane and the site was used briefly in the early 1940s during the construction of both the Quonset Point Naval Air Station and the Seabees base. All service finally ended in 1963.

From the station, the right of way crossed the Old Shore Road (now Scenic 1-A), paralleling the waterfront along what is now Steamboat Avenue.

The tracks terminated at the Wickford Landing depot and boat dock opposite about a half mile east of the main highway. The site is now the Wickford Marina, a portion of which suffered a devastating fire in the summer of 2019.

At pier side, a covered portico with several spur tracks was built to accommodate the private rail cars of those who would board the ferry for Newport. Another hand-operated turntable was located here as well as a coal bunker.

The N&W never operated more than one locomotive at a time. Although its steamships were quite comfortable, no one would accuse the N&W of extravagance with its engines. The railroad used an ungainly little engine, known as a Forney. Designed for use on urban elevated railroads, it could be operated in both directions (even though the N&W had the benefit of a pair of turntables). “Newport #1” was an 0-4-0 tank engine. In railroad terms, that meant it had no leading wheels in the front. The boiler sat squarely atop the driving wheels and the rear wheels supported the self-contained coal bunker. It would never win a beauty contest, but the sturdy little engine ably served for many years.

The N&W operated a minimum of rolling stock. Car Number One was a handsomely varnished baggage car. The line also had a combination baggage and passenger car. There was one other important asset: a little gasoline-powered maintenance car used by the track crew, light enough to be lifted off and on the tracks should a train be on the way. If necessary, the N&W could lease a passenger car or borrow motor vehicles from the New York, Providence and Boston (and later, the New Haven). Since most of their traffic consisted of the private cars of the wealthy, extra vehicles were not often needed.

The train trip itself, point to point, was only about ten minutes long. After reaching the pier, the locomotive was made ready for the return up the line. At the height of operations, the N&W maintained a busy schedule designed to meet mainline trains; the steamboat service ran four round trips a day.

The line’s big attraction was the steam ferry. It took about an hour-and-a-quarter to cross the bay from Wickford Harbor, sail down the east side of Conanicut Island, and land at Newport Harbor.

Although the roughly twelve-mile ride was usually comfortable, bad weather could occasionally pose problems. Narragansett Bay is prone to fog, in summer thunder storms could quickly strike, and in winter part of the bay waters could freeze.

Since 1831, Wickford Harbor had been marked by a lighthouse at Poplar Point. It served the harbor’s needs for some fifty years. Due to lack of marine traffic, the U.S. Lighthouse Board had questioned whether or not a light was needed. That changed with the advent of the N&W’s service to Newport. Poplar Point was darkened in 1882 (it became a private residence in 1894). It was replaced by a more modern offshore light on Old Gay Rock. This light outlived the N&W steamships by only five years. In 1930, it was replaced by an automated beacon.

In the 19th century, as bay marine traffic grew busier, the steamboat owners pressured the federal government for another lighthouse, this one to be posted at the north end of Conanicut Island. After the railroad’s Eolus ran aground on the north end of the island during a storm in the winter of 1885, the N&W put up its own beacon. Eventually, on April 1, 1886, the federal government illuminated the new Conanicut Light. It did not outlive the N&W steamship service for long; it was darkened in 1932.

From the tip of Conanicut, the ferry rounded into the East Passage where passengers could be dropped off at Jamestown. By the 1880s Conanicut had also become a popular summer destination for many wealthy visitors, many from Philadelphia.

If there was no need to stop at Jamestown, the ferry continued around Gould Island and then Rose Island. The N&W steamship entered Newport Harbor at the northern tip of Goat Island, marked by the steady green beacon of the Newport Harbor Light, popularly known as Goat Island Light. Up until the early 1960s, this light marked the principal entrance to Newport Harbor.

Completing its twelve-mile run, the N&W ferry docked at Commercial Wharf, in the heart of the city’s waterfront. Carriages, and automobiles later on, waited for passengers to disembark and then whisked them off to their opulent cottages or one of the posh hotels.

The N&W’s first steamboat came with a story of its own. It was a surplus vessel from the Civil War. The USS Eolus was sold by the War Department in August 1865. Eolus had served with distinction. Built in 1864 in New York, and first christened as Calypso, she was a side wheeler, 140 feet long and displaced 368 tons.

During the Civil War, the steam ship was assigned to the Union blockade off North Carolina. Eolus also carried mail and military messages, supplies and ammunition to the larger ships, and on occasion ferried wounded soldiers and sailors to hospital ships. She was credited with capturing the Confederate blockade runner Hope and sharing in the capture of the Confederate Lady Sterling. She also participated in the January 1865 attacks on Fort Fisher at the mouth of the Wilmington River in North Carolina.

Eolus had a walking beam engine, which made it capable of a respectable sixteen miles per hour. After the war ended, this speed made her attractive for civilian use.

Eolus began service for the N&W in 1871, when the rail and steamship service opened. Many of the so-called “400” of Newport society were regular passengers aboard the Eolus during her more than twenty years of service.

On the evening of September 27, 1888, Captain Wightman’s steamboat had a brush with disaster. A pair of large pieces of freight, bound for the Naval Torpedo Station on Goat Island, were loaded aboard in Wickford. They were placed next to the steamer trunks of Mr. and Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt. Unknown to the crew, one package destined for the Torpedo Station held carbolic acid, and the other held an explosive propellant used in torpedoes. It was illegal to transport either chemical aboard a passenger ship. Somehow the acid container broke open and started a dangerous chemical reaction, filling the compartment and the adjacent engine room with toxic fumes. A fire followed.

Eolus sounded her whistle signaling an emergency. Nearby vessels arrived to help, ready to evacuate the passengers. Fortunately, a breeze blew up. The flames and fumes dissipated and the crew went below to get things under control. Eolus returned to Wickford and docked safely, even though it had sustained some minor damage. The ship’s engineer, Alfred Miller, was credited with bravery for his action in raising the alarm just in time. Sadly, Miller died the next day of lung damage from inhaling the acid fumes.

At the height of the summer season, Eolus was making up to five round trips a day, starting at 7:30 in the morning and finishing up at 10:30 at night. Since the schedule was designed to connect with the mainline trains, it would vary over the year.

Eolus carried N&W passengers until 1892. She was sold and scrapped a year later.

Eolus was briefly succeeded by a practically new side-wheel steamer, the Tockwogh. Previously, Tockwogh had briefly served as an excursion steamer off the shores of Maryland and Delaware. On the night of April 12, 1893, she was tied up for the night in Wickford. The railroad’s night watchman discovered a fire on the ship. He sounded the alarm, but to no avail. Tockwogh burned to the waterline, a total loss less than a year after she entered service. Valued at $80,000, insurance covered only $50,000, a blow to the N&W’s coffers.

Tockwogh was succeeded by the steamer General. Over her long career, General became the most popular of the N&W boats. Of the trio of ships that sailed for the N&W, the General was, without a doubt, the finest. Built in Brooklyn in 1889, she was propeller driven, 130 feet long and displaced 332 tons. Like her two predecessors, she drew less than ten feet of water, an important feature given the relatively shallow waters at Wickford Harbor and Commercial Wharf in Newport.

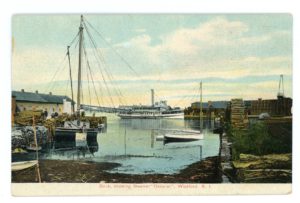

Postcard of the steamer General underway. Taken from a photograph by Wickford drug store owner Elwin (Doc) Young. He made a number of his photographs into postcards and sold them at his store. He died in 1937 at the age of 71 (Sanford Neuschatz Collection)

Although the trip across the bay was relatively brief, passengers enjoyed all the luxuries they would expect from the finest hotel. The cabins and public areas were furnished in plush velour and thick carpeting. Every night on the return trip from Newport, a band serenaded passengers from the upper deck.

The General had her own confrontations with the unpredictable waters of Narragansett Bay. The February 5, 1897 edition of the North Kingstown Standard newspaper reported, “the steamer General encountered a field of ice last Tuesday that detained her one hour and a half and forced her to miss one trip. It seems that the field was about a mile long and some six inches thick. It floated from Prudence Island. The steamer could neither go back or go ahead, so the deck hands had to get down with axes and chop her out.”

Back then, it was not uncommon for the bay, or parts of it, to freeze over during the winter. In fact, in 1918, and again in the 1930s, the West Passage between Conanicut and Saunderstown froze over so solidly that locals were able to drive their wagons and cars across to the island.

The N&W employed numerous local residents. Long time conductor William Congdon retired in 1886 and was succeeded by his step-brother Henry. Other local men included engineer John Blifford, trainman “Late” Willis, and Edwin Huling, who served as a night conductor and also a purser aboard the General.

One of the line’s long-time employees, and one of its most colorful ,was Peleg Wightman. He was born in 1831 and went to sea as a young man. He held a captain’s license by the 1860s. He was serving as mate aboard the sloop Resolution when, on September 8, 1869, as the vessel neared Wickford in increasingly rough water off Conanicut, the Resolution struck a rock, quickly broke up and began to sink. Wightman and Captain David Baker abandoned ship and clung to the mast and rigging as the wreck drifted into Spink’s Cove. They were rescued, but their two passengers perished.

Wightman spent the next few years ashore helping to plan and construct the N&W, including the pier at Wickford. He then served as the Wickford Landing station agent before he became captain of the Eolus. He went on to command the General for many years.

The Steamer General at dock in Wickford. This is another postcard from a Doc Young photograph (Sanford Neuschatz Collection)

Wightman met his end as he would have wanted. He was in the ship’s wheelhouse on February 19, 1898, heading for Newport on the 7:00 p.m. run, when he suffered a fatal heart attack. His funeral was attended by many persons from Wickford, Newport, and Providence. He was memorialized in the North Kingstown Standard in these words, “On that dark and cheerless night…while wind and wave were indulging in a chant as weird as a witches incantation, the spirit of our much esteemed captain, Peleg Wightman, in obedience to the Supreme Will, winged away on its flight to a home beyond the sea…with him the storms of the sea are o’er…God gave…He took, He will restore.” No sea captain could ask for a better eulogy.

Around the turn of the century, things were humming at the N&W. In addition to providing comfortable and convenient transportation, the line was turning a modest profit and contributing to the local economy.

While the N&W and steamship operations continued unchanged, technological developments ended its success. The advent of motor vehicles changed the way people and products moved. The luxurious steamships that plied the waters of Narragansett Bay and took passengers to and from New York were fatally affected, as were associated railroads and trolley lines.

Around the turn of the century, mirroring a financial downturn nationally, N&W revenues began a steady decline. Its fortunes took a nosedive. After 35 years in independent operation, the N&W entered into receivership. The voracious New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad swooped in and bought the line in 1909 at a bargain price. Although service remained in place (at one point the New Haven line, as it was known for short, operated a “Wickford Special” train from New York), the line’s prosperity faded in the early 20th century.

Back in Wickford, life went on. The N&W trains ran and the trolleys of the Seaview Electric Railroad continued to carry passengers south to Narragansett to relax at the beach. But after the end of World War I in 1918, the New Haven Railroad, suffering from its own postwar financial decline, started to cut corners. One victim was the N&W’s rail passenger and ferry service, which shut down in 1925.

General served until the line ceased passenger operations. General ended her career in New York City carrying visitors to the Statue of Liberty. She was finally scrapped in 1935.

Only a modest freight service serving businesses along the right-of-way continued. But after the 1938 hurricane damaged trackage from the Wickford village depot to the harbor, these operations ceased and the right of way was abandoned.

The U.S. Navy’s preparations in the early 1940s for America’s possible entry into World War II brought a brief resurgence for the N&W between Wickford and the mainline. During the early phases of construction of the Quonset Point Naval Air Station and the Naval Construction Training Center for the Seabees at Davisville, freight was brought down from the main line on the N&W. It was loaded onto trucks and brought up to the base. After a direct junction was put in place at Davisville, the N&W’s line became obsolete.

The little Wickford Village station also was a victim of progress and the construction of the Navy facilities at Quonset Point and Davisville. Since there was no longer any passenger service, there was no need for the building. It fell to the wreckers.

Because some freight service remained, there was a need for a local station agent. Rose Weaver held the position. Her office was the N&W’s once handsome 1908 combination baggage and passenger car shunted onto an unused siding. The formerly plush seating was removed, and a desk was installed along with a phone and a pot-bellied stove.

Eventually, freight service dwindled until 1961, when the Agway feed store became the line’s last remaining customer. Once a week, New Haven Railroad Switcher Number 596 brought a single freight car from Wickford Junction to the feed store, which at the time occupied the old freight house. Finally, even that service came to an end by the end of 1961. The line was abandoned two years later.

The 1908 combination car/station office car was loaded aboard a trailer and taken to the Connecticut Trolley Museum in East Windsor where it was converted into a gift shop and snack bar. The remaining tracks were removed. Today, the buildings that once served the N&W have disappeared, with the exception of the well-concealed remains of the Belleville Station and the Wickford village freight station, which was moved to become the nucleus of a dental office on nearby Updike Avenue.

Today’s adventurous souls can still walk along the N&W roadbed, although much of it is on private property. Using Google Earth, one can follow most of the old right-of-way from the mainline. At the junction, there are four track beds crossing Ten Rod Road on an overpass, built in 1939 to replace a dangerous grade crossing. The southernmost roadbed formerly served the N&W; it turns sharply south from the junction. The other vacant roadbed was a once passing track from Kingston to Davisville. The two center tracks serve the existing mainline.

A recent view of the abandoned N&W Wickford Cove Trestle looking north toward Belleville (Brian L. Wallin)

Today, sleek Amtrak trains speed up and down the Northeast corridor and MBTA commuter trains run from Wickford to Boston. Overnight freight trains rumble along the main line. On a third track from Davisville north to Providence, cargo from the Industrial Park at Quonset Point is moved without disrupting mainline service.

At Wickford Junction, none of the N&W buildings remain. The outline of the hand-operated turntable is visible in the woods behind the site of a former garden center. There are a few pieces of Westerly granite that once served as the turntable walls. Reportedly, a portion of that granite wound up in South Kingstown as part of the William C O’Neill Bike Path, which was built on the right-of-way of the old Narragansett Pier Railroad.

The sound of today’s electronic locomotive horns cannot measure up to the mournful wail of the old-fashioned steam whistles that once graced the locomotives of the Stonington Line, the New Haven Railroad, the little N&W, and the short lines that branched out to serve the Ocean State during the 19th and 20th centuries. The N&W, when no longer needed, just faded away. But, in its relatively brief lifetime, it contributed to the charm that was and still is the Ocean State.

In 1949, a local banker named George W. Gardiner self-published a colorful history of the village of Lafayette that described the local impact of railroading in the 19th and 20th centuries. The last words of his book, in an eerie way reflect the current surroundings at Wickford Junction. Gardiner wrote:

All in all, the Junction was a busy place over the years long past . . . . in its days and nights of a thriving traffic of its own. Now the roar of the big Diesel engines, the swish of streamlined trains, the rumble of the long freights and the buzz of automobiles and trucks through the underpass betoken the hectic rush of modern traffic. The once busting railroad station of Wickford Junction has been bypassed in the ruthless ‘March of Time.’

[Banner image: Postcard of the steamer General. Taken from a photograph by Wickford drug store owner Elwin (Doc) Young. He made a number of his photographs into postcards and sold them at his store. He died in 1937 at the age of 71. (Sanford Neuschatz Collection)]

Bibliography

Books

Frank Heppner, Railroads of Rhode Island (Charleston, SC: History Press 2012)

George W. Gardiner, Lafayette Rhode Island, A Few Phases of Its History from the Ice Age to the Atomic ( Providence, RI: The J.C. Hall Co., 1949)

- Edward Prentice, Through the Woods and Across the Fields to Narragansett Pier, The Seaview Railroad (Wakefield, RI: Privately printed, 1983)

Joseph E. Coduri, Rhode Island Railroad Stations (Middletown, DE: Privately printed, 2016)

Newspapers

Captain Wightman Obituary, North Kingstown Standard, February 25, 1898

- Timothy Cranston, “An ‘Armstrong’ powered a piece of North Kingstown’s history,” The Independent, June 8, 2017

- Timothy Cranston, “Postcard memories of the old Belleville train station,” The Independent, July 23, 2015

- Timothy Cranston, “Abandoned rail car found a new home,” The North East Independent, March 14, 2002

Online Sources

Edward Ozog, Rhode Island Railroads, sites.google.com/site/rhodeislandrailroads

tapatalk.com, New Haven Railroad Historical & Technical Association, New Haven RR Forum, September 15, 2005

xroads.virginia.edu, “Class and Leisure at America’s First Resort: Leisure/Other Lines”, 2001

Other

The author would like to acknowledge the generous assistance of the following: North Kingstown town historian G. Timothy Cranston; Rachel Peirce and KarenLu LaPolice of the East Greenwich Preservation Society; and Astrid Drew, Archivist of the Steamship Historical Society of America.