Five years ago, my wife Margaret and I purchased a home on Queen River in West Kingston, north of historic Usquepaugh and its Kenyon’s Grist Mill. In that time, I have been able to spot some fascinating wildlife in a fresh-water environment.

Rhode Island is dominated by Narragansett Bay and the Atlantic Ocean. The state’s maritime tradition, recreational beaches, and history related to the salty sea remain important parts of the state’s heritage. But it should not be forgotten that Rhode Island still has some extraordinary fresh-water lakes, ponds and rivers that support a variety of wildlife. These types of wildlife helped sustain Native American peoples and the first white settlers. They survived the many mills placed on ponds, rivers, and streams in the nineteenth century.

Margaret and I have been fortunate to appreciate the remarkable diversity of wildlife from the windows of our house on the Queen River. I call it Queen River but a portion of it near our house is formally known as Glen Rock Reservoir. I also thought it was called Queen’s River or Queens River, but I have since learned that the correct spelling is, surprisingly, Queen River. It was named in a recent submission to the federal government as the Queen-Usquepaugh River.

The river was likely named for Queen Quaiapan, a leader of the Narragansett tribe in the mid-seventeenth century. Queen’s Fort in North Kingstown is also named for her and is in the area of the headwaters of one of Queen River’s several tributaries.

Queen River is one of seven major rivers of the Wood-Pawcatuck watershed that recently qualified for designation in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers organization’s Wild and Scenic Rivers program. In the successful submission for that designation, Queen River was described as a “great habitat for freshwater mussels, brook trout, and amphibians.” A local newspaper article described Queen River as “one of the cleanest and coldest rivers in Rhode Island and one of the most pristine rivers in southern New England. A high priority for conservation, the river supports wild brook trout, several rare dragonflies, and an abundance of freshwater mussels.” This view is supported by the fact that the river is teeming with Painted Turtles and hosts Great Blue Herons and North American Otters, all of which flourish only in clean waters.

The waters of Queen River around our property are a combination of fresh-water pond environment and fresh-water river. From our property, it first appears that the body of water is a pond. There are numerous water lilies, pondweeds, and other plant life in the shallow water in the warm months. But the body of water beyond the pond environment is actually a river, with a narrow yet relatively deep channel flowing south. The river keeps the fresh-water renewed. It leads to an impressive waterfall at the end of Glen Rock Reservoir, just beyond Kenyon’s Grist Mill. The water then eventually feeds into to the Wood River, which flows into the Pawcatuck River and ultimately farther south past Westerly and to the Atlantic Ocean.

I do not see interesting wildlife every day when we are visiting on the Queen River. In the warm months, I will typically spot a Great Blue Heron, see several geese, hear fish jumping and splashing in the water, and listen to frogs croaking.

The most rarely sighted mammal is the North American River Otter. I have seen them on only three occasions. The first was on a freezing cold February morning, when thick ice was layered on the pond environment, but not in the flowing river channel itself. I was admiring the unique view when suddenly an otter jumped out of the channel and onto the ice. It must have felt safe there from potential predators. After prancing around for a few minutes, two more otters burst out of the channel and jumped on and play-wrestled with their sibling or friend. After perhaps ten seconds, the two other otters disengaged and jumped back into the water. The dazed otter who was the victim of this prank took a short time to realize what had happened and then it too jumped back into the frigid water to find the two pranksters.

Paul Drumm, the owner of Kenyon’s Grist Mill and operator of a kayaking business on Queen River, greatly appreciates wildlife and has seen much more than me over the years. He has shared a few stories with me. Once, he recalled, when the river was half-frozen, he saw an otter on the ice with two large fish, probably bass. The otter was enjoying his meal and then, apparently satiated, jumped back into the water, leaving the fish behind. Suddenly, an osprey appeared and took off with one of the fish, its talons holding the fish firmly.

In five years I have seen otter on only two other occasions. They were swimming in the river in front of our house at a distance of about seventy-five yards.

The following is a 2022 update of this article. In August of this summer, my wife, Margaret, and I saw a terrific struggle, full of splashing and thrashing about, again in the river in front of our house. For five minutes, we could not figure out what was going on. Margaret handed me a pair of binoculars and I finally figured it out: an adult otter was attacking a good-sized snapping turtle, with a shell about eighteen inches in diameter. The otter grabbed both sides of the turtle’s shell as you would carrying a door you were about to install; the otter, on its back, twirled it underwater and out of water three times or more. That did not work. The otter tried biting the turtle’s front section, and I got a good look of is open jaws and sharp teeth. That did not work either; the snapper had wisely retracted its head inside its body. The otter then swam around the floating turtle shell, its long tail trailing behind it, trying to figure out what to do next. The otter attacked once more, dunking the turtle underwater for about seven seconds, but that attempt failed as well. Frustrated, the otter gave up and swam away. The turtle shell floated all alone in the river for about ten minutes. I wondered if the turtle was harmed. The next time I looked, the shell was gone. The snapper had survived and swum away. The otter would have to prey on smaller turtles.

River Otter feast on fish, frogs, turtles, crayfish, mussels, birds, and eggs. They particularly thrive where there are large fish, such as bass. A friend who has fished on Queen River over the years informed me that bass used to be abundant on the river, but then the water lilies and other river vegetation for some unknown reason receded, and the bass became fewer, which in turn also reduced the otter population. Now the shallow-water vegetation in the river is abundant (almost too much so) and the bass have returned—as have the otter.

Another rare site is the North American Beaver, the country’s largest rodent. They are most active at night. The best time to see a beaver during the day is in rainy weather. This year, we were lucky and a beaver created a new lodge around the corner from our house. We could occasionally see it swimming to and from the area, and then disappearing under the water. Beaver enter their lodges under water, as protection against predators.

Once the beaver came crawling up onto our small peninsula of land. It was tiny, about twelve inches high, not including the broad, flat ten-inch long tail. It was looking for food. A beaver’s diet includes water vegetation, as well as tree bark and cambium (the softer tissue under the bark).

Beaver had been on our small peninsula before then. Beaver had “skirted” several of our trees that bordered the river. By removing the bark from the tree in a one-foot circle around the bottom of the tree, nutrients from the roots have a harder time being transported up the tree and the tree eventually dies. When the tree falls in the water, the beaver is happy, supplied with easily accessible sticks and branches for its lodge. But the dark-brown beaver with a paddle-shaped tail, after it arrived at our shoreline, saw us pointing at it. After a few moments it retreated to the safety of the water and we have never seen it again on our property.

A beaver “skirted” this tree on the author’s property. Unfortunately, eventually, the tree will die (Christian McBurney)

My wife and I sometimes paddle up the river towards Dugway Bridge in kayaks or a canoe (it is some of the best fresh-water kayaking and canoeing in the state). A few years ago, up one of the channels, there was a beaver lodge about six feet high, made up of sticks and mud. We never saw the beaver there. Paul Drumm and a friend of his once decided to kayak to its lodge at night. Sure enough, when they arrived at the lodge, and Paul used his hand to slap the water, the beaver turned up. The beaver thought the splashing was the sign of a potential mate and popped his head above the water for a look, but saw only Paul’s mug. One season a beaver used to come down to Paul’s dock almost nightly at about 9:30 p.m., apparently to feed on the chestnuts. Paul also recently spotted a baby beaver near his mill, a rare sight indeed.

There is a good-sized beaver lodge on the east side of the rich swamp at nearby Punch Bowl Trail. Margaret and I have walked by the swamp in the Punch Bowl (for which the road is named) perhaps fifty times, but we have seen the beaver only once—as it swam toward its lodge in rainy weather. The beaver constantly tries to block the culvert that allows overflow water to go under the road from the beaver’s side of the swamp to the swamp on the opposite side of the road. But the state Department of Environmental Management (DEM), after many tries, has figured out how to build a culvert to keep the beaver from succeeding.

In the old days, DEM would have trapped and killed the beaver, or moved the beaver to a remote area in a state park. But now environmentalists realize the key role that beaver play in creating marshes that host a rich and diverse wildlife and plant environment.

Once Margaret and I saw what we believed was a family of muskrats swim over to our spit of land and check it out. The mother had about five youngsters following her. That was our sole sighting of muskrats. Muskrats make lodges made of grasses, but we have never seen one.

Surprisingly, we have yet to see a raccoon. We have also not seen any mink.

We have not seen any deer on our property. I think they do not want to be trapped on a peninsula.

Naturally, water birds are an important part of the wildlife on Queen River. The most amazing bird is the Great Blue Heron. I typically see one in the warm months at least once a day, flying to or from a small cove to the right of our house. They often fly past our house at eye level, which is very neat to see. They can stand almost four feet tall and their wingspans can be as much as seven feet. They are the state’s largest wading bird. When they fly, their necks are in an “S” shape, their spindly legs trail behind and their wings move slowly but gracefully.

A Great Blue Heron fishing at the waterfall in Usquepaug near Kenyon’s Grist Mill, still part of Queen River (Christian McBurney)

When a heron fishes, it stands perfectly still in shallow water, stretches its neck, and hopes that in can spear a fish swimming by with its sharp beak. Herons eat their prey whole.

If a Great Blue Heron stands sideways, it can be seen, but if it is facing the viewer directly, the heron is so skinny that it is difficult to see it. Adults weigh only five to eight pounds.

Paul Drumm told me he has seen Great Blue Herons “fishing” at the waterfall next to his mill. They stand just beyond the rushing water where fish like to congregate. Two days after he told me this, I saw one at the waterfall too, my first time.

One of the remarkable features of Great Blue Herons is the angry sound they make when they are annoyed. It typically happens at night, when they are looking for a place to bed down high in a tree. One moonless evening I heard the most tremendous, angry and deep squawk. It was a Great Blue Heron trying to get comfortable but not succeeding. The sound is similar to what you would expect from a flying dinosaur—the pterodactyl. (If you remember the cartoon Johnny Quest in the late 1960s, you will recall the scene of the pterodactyl squawking—a Great Blue Heron sounds like that.) Perhaps this is not surprising, since it resembles a prehistoric bird; in fact the species dates back 1.8 million years.

This summer, for the first time, there were two Great Blue Herons—a large mature one, and a smaller, younger one. It is estimated that only one in five juveniles survives to breed in its third spring. The greatest reason for such high mortality appears to be the difficulty in learning to catch large fish.

They are difficult to photograph. If they see a human get close, they get spooked and fly away.

As a group, Canada Geese are the most impressive. They arrive in the Fall and I have seen flocks of more than one hundred. When they take off or land, all together, they make a tremendous racket. Most of them are honking loudly and splash as they rise or land on the water. When they take off, they begin by running on top of the water. Seeing a group of twenty to thirty do that is remarkable. Typically, some geese stay year-round—from a few to ten each year.

Three Canada Geese in the act of landing on Queen River, joining other Canada Geese in November 2020 (Christian McBurney)

Mallard ducks appear as well, with their distinctive coloring, especially the dark green on the heads of the males. The ducks get along fine with the geese, all feeding in the river.

One of my favorite water birds is the colorful Wood Duck. They are small and have a short wing span, but they make up for it by flapping their wings with tremendous rapidity and speed along in flight. The Wood Ducks, while searching for food, can disappear underwater for up to 30 seconds. I was surprised to see that geese, too, sometimes completely submerge for a few seconds, apparently to clean themselves.

This year we saw Osprey for the first time, but only for several weeks. Three of them showed up. It appeared one was a female, as the other two took turns chasing the third one. It must have been mating season. They occasionally searched for food, diving into the river and sometimes coming up with a silvery fish squirming in their talons.

We have also seen woodpeckers, yellow finches, and hummingbirds. The Red-headed Woodpecker is a medium-sized woodpecker about the size of a robin. It can be heard pecking away at dead trees trying to make a nest high above the ground. Remarkably, it stores live grasshoppers by wedging them into crevices so tightly that they cannot escape. The Red-headed Woodpecker population nationally has been falling, but they become more numerous where beavers are at work flooding fields.

There are more ordinary birds too that bring joy. Recently, I saw six Blue Jays feeding in the same area. I did not know they liked to hang out with each other.

When Margaret and I go for a kayak trip up the river, Red-winged Blackbirds are a common sight, especially in and around the cattails and tall grasses. They try to distract intruders from their nests by flying away from them, making a distinctive chak-chak sound. The black, red-winged blackbirds are the males of the species.

After going under Dugway Bridge, the kayaker enters a bird sanctuary owned by the Rhode Island Audubon Society, a pristine area that includes wonderful pine forests. Soon the channel becomes too narrow, and the kayaker must begin the journey back home.

All is not necessarily quiet and ideal on the river. After all, some animals prey on others. On several occasions in the middle of the night Margaret and I were distressed to hear the excited yelping and yapping of coyotes up the river and on the opposite river bank, where a turf farm is located. Perhaps the coyotes discovered a goose’s nesting place.

Of course, there are various types of reptiles living in the river, including fish (such as bass, trout and crappie), Painted Turtles, Snapping Turtles, and frogs.

One animal that does venture onto our land occasionally is the Snapping Turtle. These large, prehistoric-looking turtles with sharp beaks, strong jaws and massive heads spend most all of their time in the water. I occasionally see one with its head and neck above the water as it floats down the channel. The females lay their eggs on land, usually in the Spring. We have had two large females with impressive shells try to make their nests in our driveway. Once they realize that the driveway is occupied by humans, they move on. I have heard that there is no reported case of a snapping turtle removing a human finger or toe; but their bites can be painful!

A female Snapping Turtle thinks about laying her eggs next to our house in March 2020 (Christian McBurney)

One reptile I have not seen on the river is a long, black water snake—the Northern Water Snake. Paul Drumm says he has seen them weaving on top of the water in “S” shapes, their heads just above the water. He has also seen them sunning themselves on rocks at the waterfall. Their presence should discourage any humans from swimming in the river!

The dominant sound on the river from June to July is of bullfrogs croaking loudly at night. The frogs, particularly Green Frogs, thrive in the shallow water filled with water lilies, a pond-like environment. But they sure can make a racket, especially when combined with the peepers chirping in the trees. A few overnight guests of ours have had difficulty sleeping at night, the distinct “Gump!” croaks of the bullfrogs are so loud. Bullfrogs croak mainly to attract their mates. Female frogs prefer males that can produce a croak with high intensity and low frequency. In August, it is sad to hear a lone croak or two—it appears the bullfrog has still not found a mate.

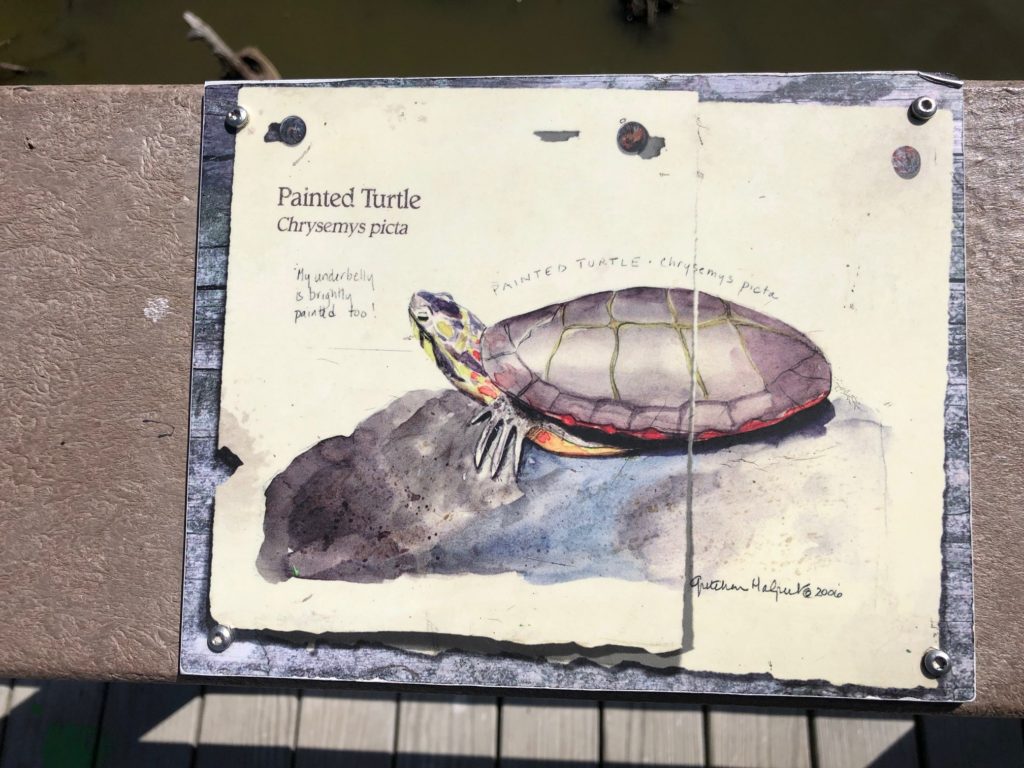

Last, but not least, are the wonderful Painted Turtles. They have painted colors on their undersides as well as on their outer shells To thrive, Painted Turtles need shallow fresh waters with soft bottoms, basking sites, and aquatic vegetation. On a good day up the river kayaking, we might see 20 or 30 of them, all different sizes, sunning themselves on various branches sticking out of the water. They like to bask in small groups. When they sense us, most drop into the water—plop, plop—they disappear. But sometimes a perfect sunning spot is too difficult to give up easily, so the turtle remains in place, in all its colorful glory.

Queen River has a unique environment dating back centuries. It is worth preserving, most importantly, by ensuring that the waters remain as unpolluted as possible.

There are potential issues. Will new housing or other development be allowed near the currently wild banks of Queen River? What about the water that a nearby turf farm takes from the river each summer? And what is the impact on the river’s ecology from any pesticides used at the turf farm and other farms along the river?

There are other places to see fresh-water environments, such as in the Great Swamp Wildlife Management Area (easily accessed from the bike trail starting at Kingston Station but from other locations too for hiking), Burlingame State Park (good for songbird watching), and Trustom Pond National Wildlife Refuge (a great place for seeing Great Blue Herons).

In addition to Queen River, the other six rivers of the Wood-Pawcatuck watershed are (in alphabetical order) Beaver River, Chipuxet River, Green Fall-Ashaway River, Pawcatuck River, Shunock River (the only one solely in Connecticut), and Wood River. This watershed is the sole source of drinking water for thousands of people in southern Rhode Island (as well as in southern Connecticut).