In 2003, a dramatic movie about a Depression-era race horse and his oversized jockey became a top box office film hit. This story of hope and perseverance was woven into a story about a down-and-out jockey, a heartbroken horse owner, a drifter horse trainer, and the eventual rise of an undersized horse. It is no coincidence that near the former Narragansett Park Race Track in Pawtucket—now a Building 19 retail store—you will discover city streets named War Admiral and Seabiscuit Place. Yet many Pawtucket residents do not know the origin of those street names or that the real-life jockey whose story was told in this film lived out his middle years in their city.

The movie “Seabiscuit” was based on the critically-acclaimed, best-selling, non-fiction book Seabiscuit: An American Legend, penned by Washington, D.C. writer Laura Hillenbrand and published in 1999. It was about a horse that was said to be too small to win, and the hard-luck jockey who rode her.

The iconic jockey who was one of the main characters in the book and movie was John M. Pollard. Born in Canada in 1909, his moniker became “Red,” as he was known for his flaming red hair.

Red and his wife Agnes called 249 Vine Street in Pawtucket’s Darlington neighborhood their home. Their children, Norah and John would grow up and receive their formal education in Pawtucket’s public schools. At the end of their lives, Red and Agnes would be buried a stone’s throw from their modest Vine St. home, in Notre Dame Cemetery on Daggett Avenue. Pollard died in 1981, and two weeks later Agnes would follow. They share the same gravestone.

Pollard became a household name to tens of millions of aging baby boomers who either read Hillenbrand’s book, ranked No. 1 on the New York Times bestsellers list for a total of 42 weeks, or watched the 140 minute Seabiscuit film, which was nominated for an Academy Award for best picture.

At 5’ 7”, Red was taller than most jockeys. Also, most jockeys weighed less, enabling their racehorses to go faster. Red was also blind in his right eye, making it more difficult to spot his rivals on the racecourse. He was at a disadvantage in his sport from the beginning.

But Red succeeded, spectacularly. According to the Jockeys Guild, the book-loving jockey rode Seabiscuit, America’s most beloved thoroughbred racehorse, 30 times, and won 18 of those races. Red and Seabiscuit were considered the top riding team of the times. Two films and a book would capture his greatest ride on Seabiscuit, winning $100,000 in 1940 at the Santa Anita Handicap.

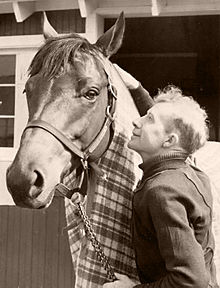

Red Pollard sitting on Seabiscuit, possibly at the Santa Anita Park in 1939 or 1940. Sitting on the horse whose rear end is in the photo is Charles Howard, Seabiscuit’s owner. This photograph could have been taken by Red’s wife, Agnes (Nora Christianson Collection)

Yet over his 30-year career, fame and fortune evaded Pollard, who suffered a lifetime of severe injuries from serious spills resulting in numerous hospitalizations for a broken hip, ribs, arm, and a leg. One spill kept him bedridden for months before he could ride again.

For Pollard, “you just made your own luck and certain things that happen to you.” Life to him was a crap shoot.

Coming to Pawtucket

The accident-prone Pollard was severely injured by the weight of a fallen horse in February 1938 at the San Carlos Handicap. Nine months later, back in the saddle, the unlucky jockey shattered a bone in his leg during a workout while riding a runaway horse. This injury kept him from riding Seabiscuit at Pimlico in 1938 in the legendary race between Seabiscuit and War Admiral. Seabiscuit won and was named horse of the year. On the plus side, his severe leg injury led him to the love of his life, Agnes M. Conlon.

I had the pleasure of interviewing Norah (Pollard) Christianson, the jockey’s daughter, for this article. She now lives in Stratford, Connecticut. According to Norah, marriage put Pawtucket on Pollard’s radar screen. Recovering from the compound fracture in his leg at Boston’s Winthrop Hospital, the jockey captured the attention of a certain nurse by reciting poetry. That nurse, Agnes Conlon, and Red, fell in love in 1938 and got married the next year. The couple would have two children during their 40-year marriage.

Pawtucket was an ideal place for Pollard to live because the city was centrally located to New England’s racing circuit, added Christianson. He could easily get to the Narragansett Race Track and Lincoln Downs in Rhode Island, and Suffolk Downs in Massachusetts, and scoot up to Scarborough Downs Race Track in Maine. Moreover, in the winter season he could easily travel to Florida and hit that state’s race track circuit.

Pawtucket also worked for Agnes. Just five minutes from their home, Agnes took a job at Pawtucket’s Memorial Hospital, working as a registered nurse in the emergency room. Norah Christianson, now age 72, noted that it was convenient for her mother to drive an hour from Pawtucket to visit her parents and ten siblings, all of whom lived in Brookline, Massachusetts.

Riding injuries kept Pollard from serving in the military during World War II. Norah noted that her father worked as a foreman and helped to supervise the construction of Liberty Ships at the Walsh-Kaiser shipyard in Providence, the largest manufacturing enterprise in the state’s history. At war’s end, Red continued to ride horses until the age of 46, when in 1955 he was just physically unable to do so. For a time, Norah recalled, her father “worked at Narragansett [Race Track], mentored young jockeys, and then worked as a mail sorter at the track. After that, he worked as a valet for other jockeys until he finally retired for good. The track was always my dad’s ‘community’ until it closed in 1978.”

New York newspaper article from its June 27, 1935 edition announces a victory by Seabiscuit at Narragansett Racetrack

Sipping Whisky, Reading Great Poetry

Pollard, whose education ended at fourth grade, had a love for poetry and the classics, recalled his daughter. Always on the move between race tracks, he carried his favorite pocket volumes of Shakespeare, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Robert Service’s “Songs of the Sourdough,” and Omar Khayyam’s “Rubaiyat.” Being a poetry lover, frequent stays at the hospital would “allow my father to read a lot and memorize,” she noted.

She also remembers her father sipping a little bit of whiskey as he would recite poetry for the family after dinner. “We just absorbed the experience, not realizing we were learning.”

Pollard traveled the racetrack circuit for months at a time, states Christianson. When in town, her father would take her and her brother, John, to Pinault’s Drug Store on Newport Avenue, enjoy a movie at the Darlton Theater, or visit Kip’s Restaurant. “I remember Pinault’s had a soda fountain that made the best home-made honey dew melon ice cream,” Norah remembered wistfully. Many a day Pollard would stop at the Texaco gas station, located at Armistice Boulevard and York Avenue, to sit and talk for hours with his friends.

“Dad was a loner, a desperado, an extreme free spirit, a man obsessed with racing,” said Christianson. Before he retired, Pollard’s typical day started at 4:30 a.m. by heading to the track to exercise horses. Later in the morning, he would return home with a few of his jockey friends in their work clothes, ready to eat a hearty breakfast cooked by Agnes and to “tell jokes and talk shop.” His physically active and obsessive lifestyle in racing allowed him to relax and enjoy “puttering around his basement workshop, mow the lawn, or even put up the storm windows.”

When Christianson was seventeen, she had an inkling of her father’s fame. Mr. Winters, her Tolman High math teacher, once asked her, “is your father the jockey, Red Pollard?” Looking back she became aware that “her father did not make a fuss about his fame. He realized that when you stop being on the top, you are going to be forgotten—so—so winning that [next] race was far more important than fame and recognition.”

Being involved in local organized groups such as church, the Boy Scouts and business clubs were alien to him, Christianson added. “As my brother once said to me when we were talking about our parents, ‘Ozzie and Harriet’ they were not.”

Jockeys handle their horses in front of Narragansett Racetrack’s grandstands (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

Protecting the Jockey Community

But in 1940 Pawtucket’s jockey was tapped to be on the first board of directors of the newly established national organization, Jockeys’ Guild, which was a nationwide organized union of enormous importance for riders. Jockeys who were hurt had no financial recourse, nor did the families of jockeys who were killed, for they did not get any benefits—that is, before the Jockeys’ Guild was created. Pollard was one of the organization’s founding fathers.

Christianson added:

In the early days of the Guild, [the Nicholasville, Kentucky-based] Guild was able to introduce safety measures such as better racing environments, monitor legislation concerning racing, and providing insurance for jockeys as well as decent wages. The great achievements of the Jockeys’ Guild would be what you might call ‘my father’s community service.

Red Pollard rode into American history, overcoming a physical disability of partial blindness, accepting intense physical pain caused by severe riding injuries that fractured his bones, while humbly accepting his role in racing history, as the man who rode Seabiscuit.