At the current time, informed by our shared experience with Covid-19, most Americans now have more than just a passing familiarity with how our government and health-care system responds to an outbreak of epidemic disease. The present response is characterized by a state-federal government partnership in combination with research conducted by multinational corporations and federal entities under the oversight of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the Rhode Island Department of Health. Starting with Progressive Era reforms in the early 1900s and continuing with New Deal programs from the 1930s and Great Society programs from the 1960s, Americans have come to expect that such a “top-down” approach to solving crises is just business as usual.

This centralized approach was not always so. When faced with the threat of epidemic disease in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, the colony of Rhode Island responded by empowering local government. There were no National Institutes of Health or Center for Disease Control, let alone a Rhode Island Department of Health, to set policies or coordinate a response to pandemic or epidemic health emergencies. Instead, Rhode Island’s colony laws established a decentralized system of response to outbreaks of disease on the local level using the power of town government – in particular the town council — with occasional assistance from the colony government itself only in particular circumstances.

In nearly all cases found in Rhode Island’s colonial-era records, the threat of epidemic disease came from variola major, the virus that caused smallpox. Smallpox was the greatest threat to public health before the advent of modern medicine.

During the seventeenth century there were several recorded outbreaks of smallpox in and around Rhode Island. In 1633-34, two years before the arrival of Roger Williams from Massachusetts, the Narragansett experienced its first smallpox epidemic, where some 700 Narragansetts died.[1] Over forty years later in 1677, records from Boston note that smallpox struck southern New England in the wake of King Phillip’s War.[2] Though there is no record of whether this outbreak affected Rhode Island, it should be noted that nearly every English-built structure on mainland Rhode Island was destroyed by the Narragansett in response to the Great Swamp Massacre in December 1675. Thus, it is not surprising that a regional outbreak of smallpox noted in Boston in 1677 either went unreported in Rhode Island or the records of it have been lost. Record-keeping in the 1600s by Rhode Island’s colony and town governments was woefully inadequate, even in times of health and prosperity.

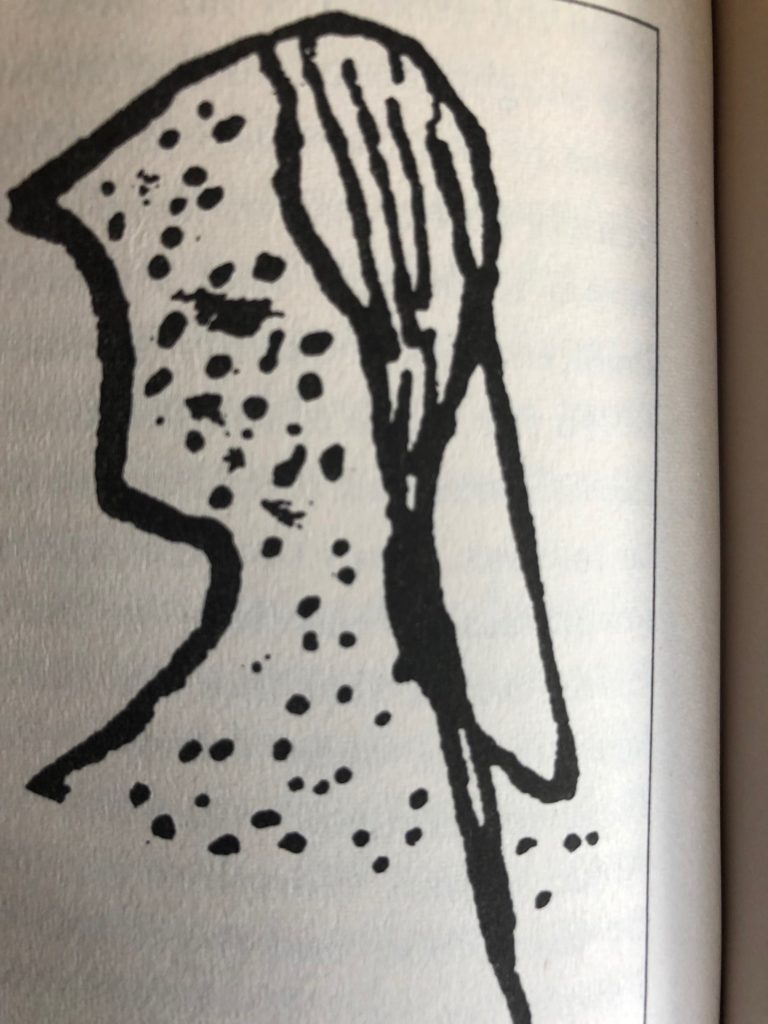

Indian drawing of man with smallpox, circa 1780-81. “Many died of smallpox.” Garrick Mallery, Picture-Writing of the American Indians, in Tenth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution (1888-89).

The first recorded outbreak of smallpox among Rhode Island settlers is described in colony records from 1690. Historian John Russell Bartlett noted that smallpox brought the government to a virtual standstill that year.[3] Given the Rhode Island’s isolation from its Puritan neighbors, this very well may have been the first occasion that smallpox struck the English living around Narragansett Bay.

The first Rhode Island law to address the need to contain the spread of infectious disease was passed significantly later, in February 1711. It seems to have been a response to the potential for contagions brought to the colony via ship. Smallpox quarantines were to be enforced by “the justice of the peace, or some combination of governor, assistants, and justices of the peace.”[4] Another outbreak of smallpox, this one in 1717, once again interrupted the business of the General Assembly.[5] In 1721 the legislature passed the first law to specifically address the spread of smallpox with “An ACT to prevent the Small Pox being brought into this Colony from the Town of Boston, &c.” Rhode Island further amended its smallpox laws again in 1743 and in 1748.

It is apparent that the General Assembly only intervened in instances where people infected with smallpox were entering various towns in the colony, creating a situation that was beyond the control of a single township and demanded a colony-wide response. This occurred when militiamen, fighting on behalf of the colony outside of Rhode Island, brought smallpox back with them, or when small pox was introduced by sailors on vessels arriving at Rhode Island ports. The General Assembly could also be called upon to ensure that the responsible parties would pay for the damages caused by any improper conduct.

The local institution the colony government empowered to deal with epidemics was the town council. Councilmen were granted vast powers over ships, taverns, and their own citizenry when it came to dealing with smallpox and other contagions. Town councils could establish quarantines and order individuals to isolate themselves from the community, while others were required to provide medical services and nursing care. Councilmen could establish “pest houses” to isolate and care for those infected by pestilence, seize personal property to be cleaned, and seek remedy in court against anyone who defied the council’s directives.[6] The range and scope of these responses testifies to the extensive police powers granted to and wielded by local officials to confront the deadly threat posed by epidemic disease, in an age before modern medical science and the miracle of vaccinations.

Of all the Rhode Island towns from the colonial era, the Washington County community of South Kingstown (which then included the present-day town of Narragansett) provides an excellent source of information due to its nearly complete set of town meeting and town council record books dating back to the founding of the town in 1723. Bruce Daniels’s 1984 study of Rhode Island town government, Dissent and Conformity on Narragansett Bay, relates that by the 1760s, Rhode Island’s town councils met on average almost exactly twice the number of times as the town meeting did, though in certain years the council met over three times as often as the town meeting.[7] It should also be noted that South Kingstown’s economy, while essentially rural, was uniquely focused on commercial agriculture though a system of plantations worked by slave labor. Most of the land in the Narragansett Country (which included South Kingstown) had been purchased cheaply in large parcels before and after King Philips War by Newport merchants, as an investment before the region was surveyed or even definitively placed under Rhode Island jurisdiction. Between the 1690 and 1720 the lands that would become South Kingstown and Narragansett were placed under the supervision of second or third sons, whose plantations, mostly worked by indentured Indians and African slaves purchased from Newport, provided the staples for the first leg in the so-called “triangular trade.” These so-called Narragansett Planters produced dairy staples, livestock and grain for trade on the Atlantic market.

The archetypical slower pace of rural life is not reflected in the frequency of South Kingstown’s town council meetings. Rather than holding fewer meetings than the mercantile towns in the colony, South Kingstown’s council was quite active. Besides being the county seat for King’s County, South Kingstown boasted a number of wealthy individuals who held important positions in not just local town government but with the colony as well.[8] In a sample of ten other Rhode Island towns for the 1760s, Bruce Daniels calculated the average number of town council meetings to be 10.6; South Kingstown averaged 13 for that decade.

Still, the town council’s schedule was not oppressive. Councilmen typically met once, perhaps twice a month, usually at a tavern or inn. But with news of smallpox, the council acted rapidly and with authority to stave off a wide-spread outbreak. During a smallpox outbreak the council met as many times as needed (or requested) until the crisis was abated. In 1760, South Kingstown experienced two outbreaks of smallpox and the council met 22 times that year; ten of those meetings (45 percent) were devoted partially or entirely to dealing with small pox.[9] In 1762 there were no smallpox outbreaks; the council met 16 times (though three of those meetings, some 19 percent, did discuss some business related to the 1760 outbreak in the course of conducting business).

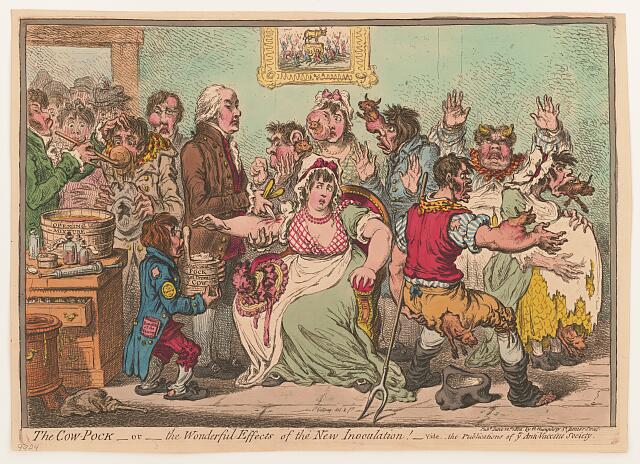

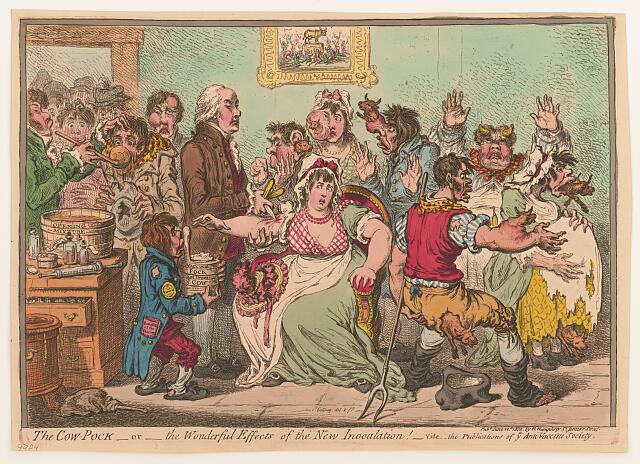

British print, circa 1802, showing people being given the smallpox cow vaccine by its inventor, Edward Jenner (in brown coast). One man has what appears to be an appendage of a cow growing from him. This print shows that anti-vaccination beliefs have a long history (Library of Congress)

Examining several of these incidents illustrates how the town council systematically responded to infectious disease while developing capacity for innovative solutions to the problem within the framework of colony laws. The smallpox outbreak in 1760 first came to the attention of the town council on December 22, 1759. The council ordered a “pest house” be created and ordered an apprentice “lately arrived from New York” sick with smallpox removed to there. The town clerk posted notices around town warning residents that the pest house was off-limits to all without “proper authority.” The council ordered a family, two other individual men, and the wife of another to be confined to their homes until it was known whether they were infected. By January 4, the council had met four more times to discuss the spread of the infection and have more residents quarantined.

The meeting of January 4 is particularly insightful. First, the council thought to order the sick wife, Hannah Greenman, to stay with relatives in Charlestown and to provide her family with certificates to go as well, but abandoned that idea later in the meeting: she was too ill to be moved. The town council considered hiring a pest house overseer, and voted to employ one John Goodbody to supervise Mrs. Greenman and any future patients at the pest house, then sent the town sergeant out “to procure” (read: press into service) an available nurse. On January 19 the council ordered the overseer of the poor to remove more sick persons to the pest house. On the 24th the council had to quarantine another house where “a Negroman in ye family of John Browning” was too ill to be brought out. Browning and his family were confined to their home along with their sick slave. By the February 11 town council meeting, the worst had passed and business concerned clean-up. In March the council announced that those with accounts related to the crises should attend the next meeting.[11]

Nine months later in early December another deadly wave of smallpox struck South Kingstown. The town meeting on December 2, 1760 voted that the town council should meet “Forthwith in order to act what they shall think Proper in order to prevent ye Spreading of small Pox,” and directed the town clerk send “a coppy of this Vote to ye President.” The town meeting also voted to put into the next warrant a vote on whether the town should build a pest house for the March meeting.[12] On December 5 the council met by “Request of ye Town,” and decided that “consideration Respecting ye small Pox” would be referred to the next council meeting on December 8. Likely at this meeting several contingencies were formulated then investigated in the interim, because unlike the January 4, 1760 meeting where the council developed a plan over the course of the meeting, at the December 8 council the response was unveiled without deliberation. First, an already empty residence along the road from Little Rest to Richmond was “Taken up as a Pest House.” The council appointed a four-man committee to investigate reports of sickness in the town; once people were positively identified as infected with smallpox this committee was to have the sick immediately removed to the pest house. The following week, the council met twice in two days. On December 13 it ordered notifications of quarantine be posted around town, created a two-man committee to oversee the pest house, and voted Hannah Greenman, who had been ill with small pox the previous winter, to be a tender of the pest house. Food and other supplies for the house were ordered, and sick persons moved there. The next day the council learned that more people were afflicted and sent them to the pest house as well. Other residents who were evidently too sick to be removed there were confined where they were. The council impressed another caretaker into employment, “v[iz] Fisher a Shoemaker.” The response to this particular outbreak even extended to the certificates the town council granted for leaving town; the clerk was directed to include an assurance on them that South Kingstown would immediately take back anyone who came down with smallpox.

The boy on the left was not vaccinated and has severe smallpox, while the boy on the right was vaccinated and has mild smallpox. Early 1900s (Historical Medical Library of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia).

The council did not meet again until January 12, 1761. Apparently, by delegating both the investigation of new cases and the supervision of the pest house to committees and individuals, the crises did not require any more direct attention from the council. During that time, five Rhode Island colony sol,diers with smallpox were kept in the town’s pest house as well.[13]

As it had the year before, the scourge had run its course by February, and the council officially dismissed nurses Hannah Greenman and Richard Fisher (the shoemaker) once the pest house had been cleaned. In April three council meetings in four days accepted the claims against the town for services rendered. Fisher’s payment for his services came to £426; Hannah Greenman received £153, and John Goodbody, received £166. Altogether the council received forty claims totaling £4,479, a substantial amount for the town. Fortunately for local taxpayers, the town was eligible to recoup £3,500 of these expenses from the colony’s war committee, as four of the five sick soldiers kept at the pest house were not from South Kingstown.[14] This incident illustrates the police powers of the town council directed at preserving the health and well-being of the community at-large. It also points to the expectation of reciprocity if having once received town aid. Though Hannah Greenman was compensated for her efforts, she was given as much choice to render aid as a nurse in 1760 as she had in falling ill with smallpox in 1759.

Though a coastal community, South Kingstown did not have an active port. Typically, the council dealt with smallpox outbreaks that took place within the town. But by virtue of its location along the southern coast of the colony, there was occasion for the town council to respond to a smallpox outbreak that arrived by sea. In the spring of 1756, the sloop Nabby out of Middletown, Connecticut, had run aground on Point Judith Smallpox was rampant on board. After the fact, it was discovered that “out of [the Nabby] one person was buried, who died with the Small-Pox, which the Master concealed, and…almost all the People belonging to said Sloop are taken down with said Distemper.” On May 4 the town council met and ordered the master of the ship to post bond and surety for damages that might accrue for bringing smallpox on shore. The sloop was also “in Dainger…to be lost” if a storm came up, so the entire cargo was ordered removed to prevent its loss, and men were employed to clean any contaminated goods “aggreable [sic] with Law.”

Meanwhile, everyone who had gone on board the sloop previous to the council’s intervention was ordered quarantined for “ye space of 24 days” until given liberty by the council. Because the sloop had also violated Rhode Island’s off-shore quarantine regulations for infected vessels, on May 8 the General Assembly ordered the vessel and its cargo taken into custody until all charges and damages were paid, and set bond at £5,000. On May 10 the council designated a pest house and met with one of the sloop’s owners who had also arrived in Point Judith. The Nabby was co-owned by a group of men and business concerns out of Middletown (at the time the largest port in Connecticut). A week later the council began to settle the first of the accounts for unloading and cleaning the cargo and continued to do so through June. In July the council tallied the final bill for the cost of cleaning the ship and cargo and all other damages, which came to £386:2. Once the owners paid the bill, the council delivered a certificate to the deputy county sheriff to release the Nabby back to its owners.[15]

In this incident, South Kingstown’s councilmen faced an uncommon emergency and reacted with a text-book response. Was their response based on a reading of colony statutes at their first emergency meeting in reaction to news of the pest ship, or had some of the councilmen witnessed a similar incident in Newport, Wickford, or even Providence, and thus acted accordingly? Whatever the case, colonial-era problem-solving was located by the colony as close to the people as possible, in the hands of colonial-era town councils. Councilmen who were expected by residents and colony officials alike to manage emergencies with proficiency and skill. Other than the honor of having their tavern dinners paid for by the largesse of the town meetiing, and the deference and respect of the town’s freemen by the reelection of the council year after year, even as they councilmen received little compensation for their time and trouble while decisively preserving life and limb in their community. These public servants followed the Latin motto, Salus populi suprema lex esto (let the welfare of the people be the supreme law)—an ancient rule of thumb that current-day policy makers might well consider.

U.S. Office of War Information employees, in 1943, receiving free inoculation against smallpox, diptheria and typhoid (Library of Congress)

Endnotes

[1] Sherburne F. Cook, “The Significance of Disease in the Extinction of the New England Indians,” Human Biology Vol. 45, No. 3, 485-508. [2] Stanley M Aronson and Lucile Newman, “God Have Mercy on This House: Being a Brief Chronicle of Smallpox in Colonial New England,” in Smallpox in the Americas 1492 to 1815: Contagion and Controversy, exhibition at the John Carter Brown Library of Brown University, December 12, 2002. [3] John Russell Bartlett (ed.), Records of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, in New England, Vol. III, 278-79.(4) Rhode Island General Assembly, The Charter and the Acts and Laws of His Majesties Colony of Rhode-Island, and Providence-Plantations in America, 1719 (Boston: John Allen, 1719) (located in Rhode Island State Archives, Providence).

[5] Bartlett, Records of Rhode Island, vol. IV, 221-22. [6] Acts and laws of the English colony of Rhode-Island and Providence-plantations, in New-England, in America, Newport, June 1767, pages 235-241 (located in the Rhode Island State Archives, Providence). [7] Bruce C. Daniels, Dissent and Conformity on Narragansett Bay: The Colonial Rhode Island Town (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1983), 64-65. [8] See Christian M. McBurney, “The South Kingstown Planters: Country Gentry in Colonial Rhode Island,” Rhode Island History, Vol. 45 No. 3 (August 1986), 81-94; also see Mark Kenneth Gardner, “As Publick As Possible: Democratic Localism and Political Economy in a Rhode Island Town Government, 1760-1820.” Master’s Thesis, Rhode Island College, 2012, 60-78. [9] The towns Daniels used in his analysis were Bristol, Cranston, East Greenwich, Portsmouth, Providence, South Kingstown, Scituate, Tiverton, Warwick, and Westerly. South Kingstown has been excluded in this average, so it is not being compared to itself. See Table 7, Average Annual Number of Meetings of Town Councils by Decade, 1710-1790, in Daniels, Dissent and Conformity on Narragansett Bay, 65. [10] South Kingstown Town Council Records, Vol. V, 77-87, South Kingstown Town Hall, South Kingstown, Rhode Island. The next meeting (see page 88), which was to examine accounts, is too faded and discolored to discern what these might have been. Ibid., 88.(11) South Kingstown Town Meeting Records, Vol. I, 298.

(12) South Kingstown Town Council Records, Vol. V, 99-105.

(13) Ibid., 105-112.

(14) The bill included £4:5 for the council’s dinner on May 17, 1756. Originally the council charged meals to the town, as was usual, but at the next meeting while receiving more accounts due related to the sloop, members voted to void the charge to the town and added it to the bill “against ye sloop Nabby”, as “sd councl mett wholley on ye affairs of small Pox brought in sd Vesel.” South Kingstown Town Council Records, Vol. V, 27-28, 31-34, and 36; Acts and Resolves of the General Assembly of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations (Newport & Providence, May 1756), page18 (located in the Rhode Island State Archives, Providence).