The 19th century was known for its social reform movements. The abolition of slavery and women’s suffrage movements are certain to top any list. But at the time temperance reform was also a major reform movement.

Slavery ended with the Civil War and women’s suffrage concluded with the passage of the 19th amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1920, but temperance or more precisely the prohibition of alcohol manufacturing, sale and consumption was an on-again-off-again issue. Most Americans know of the passage of the 18th amendment that prohibited alcohol beginning January 1, 1920, but few know much about earlier prohibition efforts in the 19th century.

In Rhode Island the proponents of temperance had their hands full as those who favored the manufacturer of alcohol, its sale and consumption fought vigorously to keep their industry free from anti-liquor legislation. Undeterred, Rhode Island reformers succeeded in pushing through prohibition measures twice in the 19th century. The first was in 1852 and it lasted for eleven years.

Prior to the Civil War, Rhode Island abounded with temperance and total abstinence societies, numerous temperance newspapers appeared in the period from the 1830s to the 1850s, and some political candidates ran for office in statewide elections under the banner of a temperance ticket.[1] Early attempts to control liquor manufacture and consumption by law occurred in 1812 and 1817 but failed to pass in the General Assembly. By 1822, however, the General Assembly enacted a law forbidding the sale of rum, wine, or strong liquor within one mile of any meeting held for the worship of God.

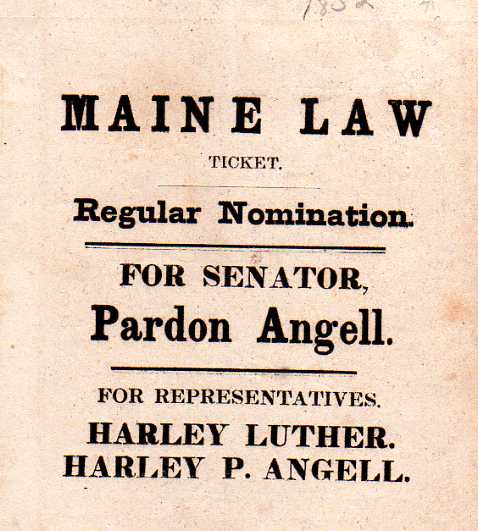

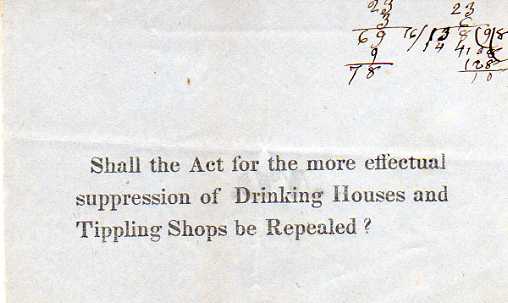

The first experiment with prohibition in Rhode Island occurred in May 1852 when the General Assembly enacted a law to suppress the liquor trade.[2] This law was commonly referred to as the Liquor Law or the Maine Liquor Law. (See Figure1). However, in order to get this law through both houses of the General Assembly and to satisfy both major political parties at the times (the Whigs and Democrats), a proviso was attached that required the law to be set before the voters at the next statewide election in April 1853.[3] (See Figure 2) The law was approved by a majority of nearly one thousand votes.

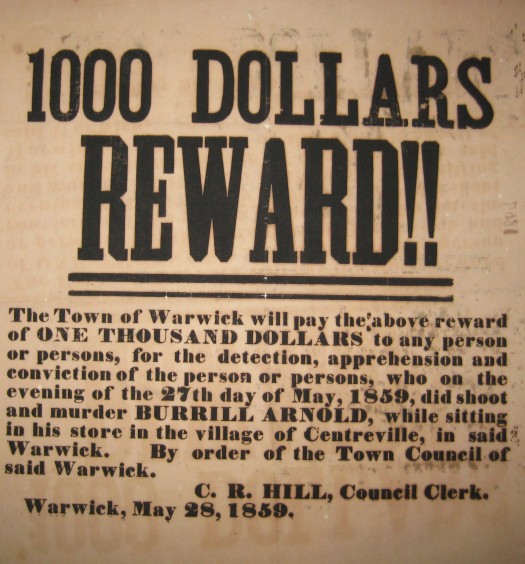

During the eleven years in which the state observed prohibition there were many instances of pro-liquor supporters resorting to intimidation of prohibitionists. The most egregious incident was the cold-blooded murder of Burrill Arnold on May 27, 1859, in the Warwick village of Centreville (now West Warwick).[4] While the murderer was never identified, one local newspaper noted of Arnold, “He was a very active temperance man, and was a member of a committee raised for the prosecution of those engaged in the liquor traffic; and his efficiency in this cause is considered by many of his friends as the motive that lead to his assassination.”[5]

The 1853 liquor law received many legal challenges throughout the period it was in force. In 1863, during the Civil War, it was finally repealed and replaced with a license law. Perhaps returning soldiers from fierce battles in the South refused to put up with prohibition. It would not be until well after the Civil War that a Rhode Island prohibition political party developed and a second experiment with prohibition occurred.

An April election ballot approving the state’s liquor law (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

Political Failure during the 1870s

During the 1870s those in favor of prohibition put forth candidates for political office. By 1874 there was significant support in the General Assembly to attempt another prohibitory law, but it came late in the session and never received sufficient support to go into force. As Amasa M. Eaton noted on the floor of the House of Representatives, “Prohibitory law has in every instance proved a complete failure for the last thirty years.”[6] John H. Stiness would remark eight years after Eaton’s speech, “no law will enforce itself nor will any law be practically efficient beyond the moral sense and interest of the people.”[7] The General Assembly just lacked a majority to enact any supporting laws for effective enforcement of prohibition.

The concept of a Prohibition political party did not manifest itself until the election of 1875 when it endorsed Rowland Hazard, the Republican candidate for governor who ran on a prohibitory ticket. To a large degree the prohibitionists were comprised of a rebellious faction within the Republican party. It was not unusual for the prohibitionists to head its ticket with the Republican gubernatorial candidate. However, some of the down ticket candidates were prohibitionists and were not to be found on the Republican ticket. This practice of a mixed ticket would be the norm until the election of 1881 when the party headed its ticket with Frank Allen. It was the very first time that the prohibitionist headed their ticket without co-opting the Republican party’s nominee.

Allen came late to the election. Initially the Prohibitory State Central Committee nominated Albert Howard for governor, but with just days to go before the election, Howard declined the honor. Newspapers reported the prohibitionist would place the Republican nominee Arthur Littlefield to head its ticket; in fact election ballots for the prohibitionist were printed with Littlefield as its candidate for governor. Ultimately the prohibitionists settled on a different gubernatorial candidate. Frank Allen agreed to run for office; but there was little too time to promote him on the party’s ticket. The party never had numerous members and in each previous election it garnered very few votes. The election of 1881 was no different: Allen received only 253 votes out of a total of 16,201 votes cast statewide. Following such a poor showing the party would not run its own candidate again until the election of 1886.

In 1886, following numerous prior attempts to pass legislation curtailing alcohol consumption or its manufacture, the General Assembly drafted a constitutional amendment and placed it before the electorate for ratification. The amendment surprisingly passed readily by a margin of 5,883 votes out of a total 24,343 votes. The amendment’s exact wording read: “Article V – The manufacture and sale of intoxicating liquors to be used as a beverage shall be prohibited. The general assembly shall provide by law for carrying this article into effect.” It was the second time in nearly thirty-five years that the state would experiment with prohibition.

Following the vote, the Providence Journal warned, “The moral and political evils which have been rebuked, have not been killed. Their forces are persistent and powerful. The appetites and the selfish interests of those who cater to them will remain and will seek their gratification. The venal and degrading influences that make a trade of politics, will by no means be abolished. The contest will have to be continuous.”[8]

With the adoption of the amendment, it was up to the state and individual cities and towns to enforce the law. A new law enacted at the May session of the General Assembly called for forfeiture, fines, and jail sentences for those convicted of trafficking in intoxicating liquors. Unfortunately, cities and towns did little to provide the enforcement of the law. As noted by Clarence Brigham, “the prohibitory method proved far from satisfactory. The violation and defiance of the law were general, and cases were rarely pressed.”[9]

The notable exception to lax enforcement of the prohibitory law was the town of East Greenwich.[10] That town’s rigorous enforcement of the new amendment soon led to dire consequences, which became known as the “East Greenwich Outrage.”

The East Greenwich Outrage

The February 22, 1888 edition of The Providence Journal noted, “The history of the rum traffic in East Greenwich cannot but be of interest, for it has been thorough and searching. For more than five years there has been waged in East Greenwich a determined fight against the rum traffic. It has been entered into by some of the most prominent people of the place, and the clergy have aided in the work by not only advocating prohibition from the pulpit, but by active labor in making seizures and causing the violators of the law to be apprehended.”

Two such East Greenwich leading prohibition advocates were Rev. O.H. Still, the town’s Baptist minister, and Samuel W.K. Allen, a lawyer. Both men performed as special constables and were extremely active and successful in enforcement of the state’s liquor laws and rooting out violators. The weekly newspaper, The Rhode Island Pendulum, reported numerous incidents in which both men were instrumental in the confiscation of contraband and the prosecution of its owners resulting in fines and jail sentences. In one instance the search of a wagon suspected of transporting contraband led to a physical shoving match in which the wagoner filed assault charges against Still and Allen.

It was not surprising that the rigorous enforcement of the law created enemies along the way. Resentment of Still and Allen’s enforcement methods eventually led to violence. On Sunday morning February 19, 1888, Still’s home was rocked by an explosion, and later that day arsenic was discovered in the well and a nearby bucket at the home of Samuel Allen. The Providence Journal for February 22 referred to the incident in a headline that read “The Greenwich Outrage—Dastardly Attempt Upon the Lives of Temperance Men.”

The attempted arson at the Reverend Still’s home and the poisoning of Samuel Allen’s well did little to deter either man. They continued to enforce Rhode Island’s prohibition law rigorously through the remainder of 1888 and into 1889. However, their efforts would soon come to a halt as another constitutional amendment was proposed to repeal the prohibition amendment. The call for repeal would cause another split within the Republican party’s ranks that would lead to the formation of the Law Enforcement Party.

The Law Enforcement Party

The Law Enforcement Party was formed by concerned Republicans who bolted from their party. In the press the party was often referred to as the Fourth Party, coming behind the Republican, Democratic and Prohibition parties. The Law Enforcement party essentially had the same agenda as the Prohibition Party in that it did not want to see Article V repealed. Why it did not join forces with the prohibitionist was best said by the Providence Evening Telegram: “The bolters, like their brethren of the Prohibitory party, are desirous of sending to the next General Assembly men pledged against submitting the amendment to the people, but they would rather take a dose of poison than vote a straight Prohibitory ticket, so they called a Law Enforcement Convention for the nomination of State officers.”[11]

The first evidence of a split in the Republican party manifested itself when in mid-March 1889 there was a call for a caucus to be held at the Franklin Lyceum Hall in Providence on March 15. This caucus passed several resolutions. The first called for a state convention to be held on March 22 in order to nominate candidates for general officers in the coming election on April 3. Interestingly the caucus specified that the convention should be held after the Republican State Convention, an obvious attempt to know what the Republican party’s platform and strategy would be before its convention.

The Law Enforcement Party’s convention was held in Providence’s Blackstone Hall on March 22, the day following the Republican Party’s convention.[12] Acting convention chairman Henry Metcalf called out the Republican Party’s leadership, noting “While the newly constructed platform of that political party, which many of us have warmly supported and defended, by its words condemns unfaithful officials, [yet] such officials still hold the most important positions in party management… While that party declares an obligation to a minority to resubmit [the question of a prohibitory constitutional amendment], the issue on which that minority was defeated, the claim of the majority as established according to law, is practically repudiated, and its respectful presentation of its claim to consideration is treated with contempt.” Often referred to as “the bolters” or “anti-resubmissionists,” the Law Enforcement Party’s members were “largely composed of thinking, conscientious men … the party has not yet arrived at the condition when it comes and goes at the beck of a few political bosses.”[13] Metcalf further chastised the Republican Party leadership when he said, “There can be no room for reasonable doubt that certain managers of the Republican Party, self-appointed or otherwise, have undertaken to deliver the Republican forces of the State in aid of the plans and wishes of law-breakers.” This reference to self-appointed managers is most likely a reference to Republican Party boss Charles Brayton, among others.

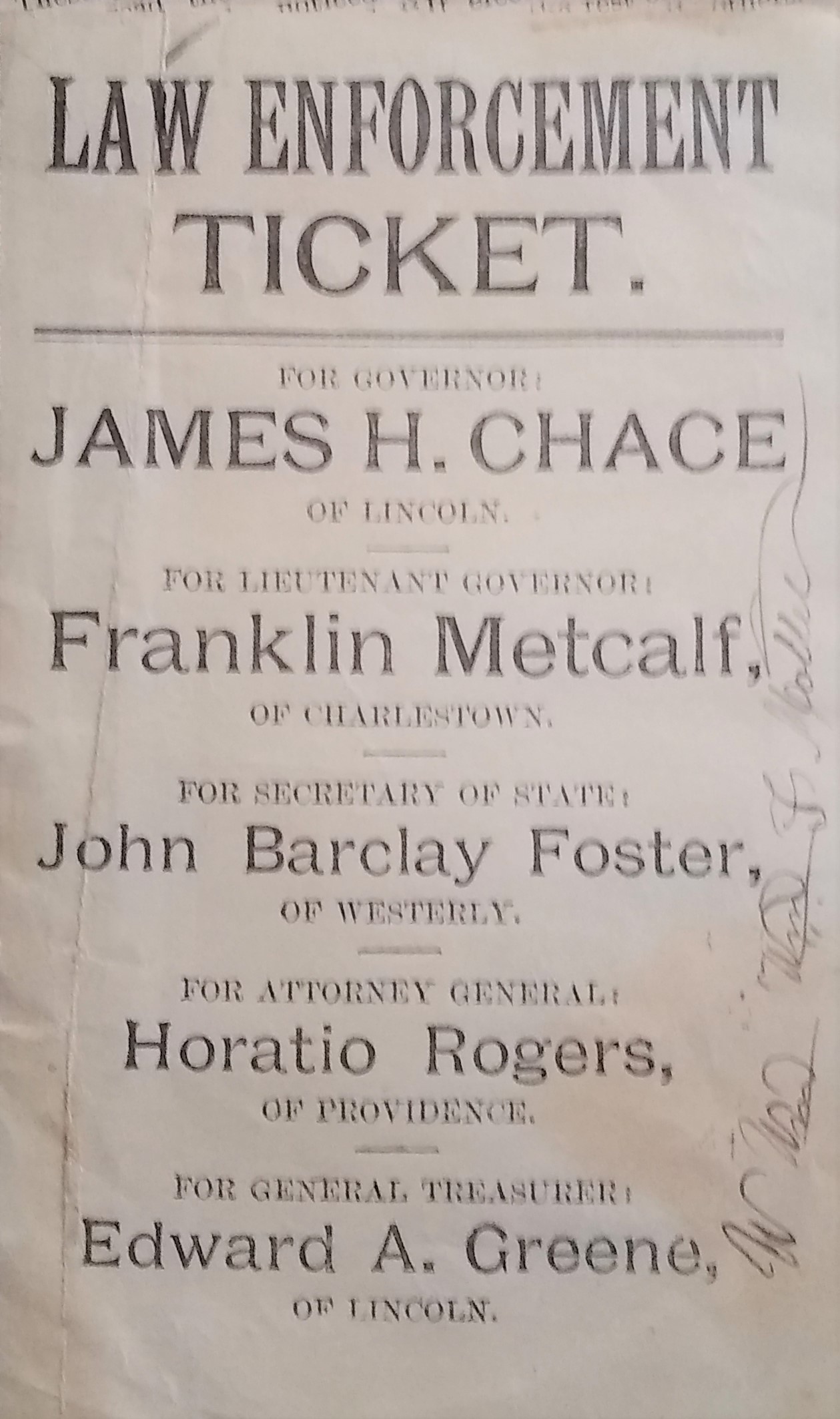

The convention’s committee on nominations reported out with James H. Chace for governor, Franklin Metcalf for lieutenant governor, J. Barclay Foster for secretary of state, Horatio Rogers for attorney general and Edward A. Greene for general treasurer. All candidates were unanimously approved from the floor of the convention. (See Figure 3)

Other than Horatio Rogers, all the candidates were political newcomers, never having served in any elected political office. Rogers, a highly respected individual, was the incumbent attorney general of Rhode Island and was also a candidate on the Republican ticket in 1889. All these candidates were accomplished businessmen and under normal circumstances would have been solidly behind the Republican Party.

Of the sixteen resolutions passed by the convention of interest is the fourth resolution “No earnest effort however has been made to enforce the law in the State as a whole, particularly in Providence; but on the other hand, every hinderance to enforcement has been thrown in the way by official neglect, and by influential newspapers.” The role of newspapers in shaping public opinion cannot be underestimated. Mostly marginalized in the Democratic press, the Law Enforcement party had a difficult time making its case before the electorate for retaining Article V of the constitution. As the convention was coming to an end, Metcalf warned the delegates “the press of the State was pretty generally against them and they could not hope to promulgate their views and push their work through the columns of the newspapers. Hence there would be work for the committee to devise means of making themselves known and pushing theirs.”

Following the Law Enforcement Party’s convention, there were less than two weeks to find candidates to run for seats in the General Assembly. With so little time the party was not able to field candidates for all cities and towns. Promoting the party’s agenda was also difficult with a hostile press that favored repeal of the prohibition amendment.

Election day on April 3rd proved problematic for all political parties. Because the Law Enforcement Party received 3,597 votes and the Prohibition Party 1,346, it was enough to cause a “no choice” as no one candidate received a majority as required by law. The Democrat, John Davis, out polled all others with 21,289 votes. In a distant second was the Republican, Herbert Ladd, with 16,870 votes. With a total of 43,114 votes, the election of 1889 was the largest polled election to date in Rhode (Island, even exceeding the presidential election of the previous year.

With no winner for governor the election was decided in grand assembly by the General Assembly. As the majority of the senators and representatives were Republicans the choice was for Herbert Ladd even though he was significantly outpolled by John Davis.

For the Law Enforcement Party, matters appeared glum as the day following the election newspapers reported the composition of the newly elected legislature had sufficient support for resubmission of the prohibition amendment. But that vote would not take place until June 20, after the new General Assembly convened and framed a new amendment to place before the electorate. By late May the General Assembly (with little discussion) drafted wording for the new amendment to repeal Article V.

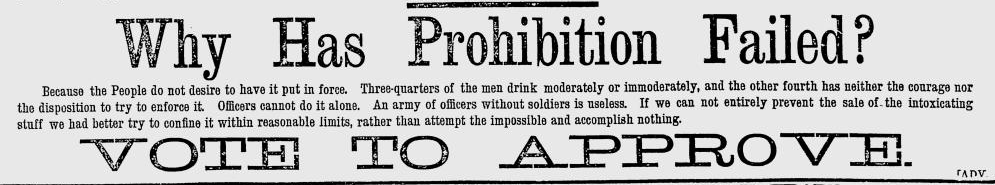

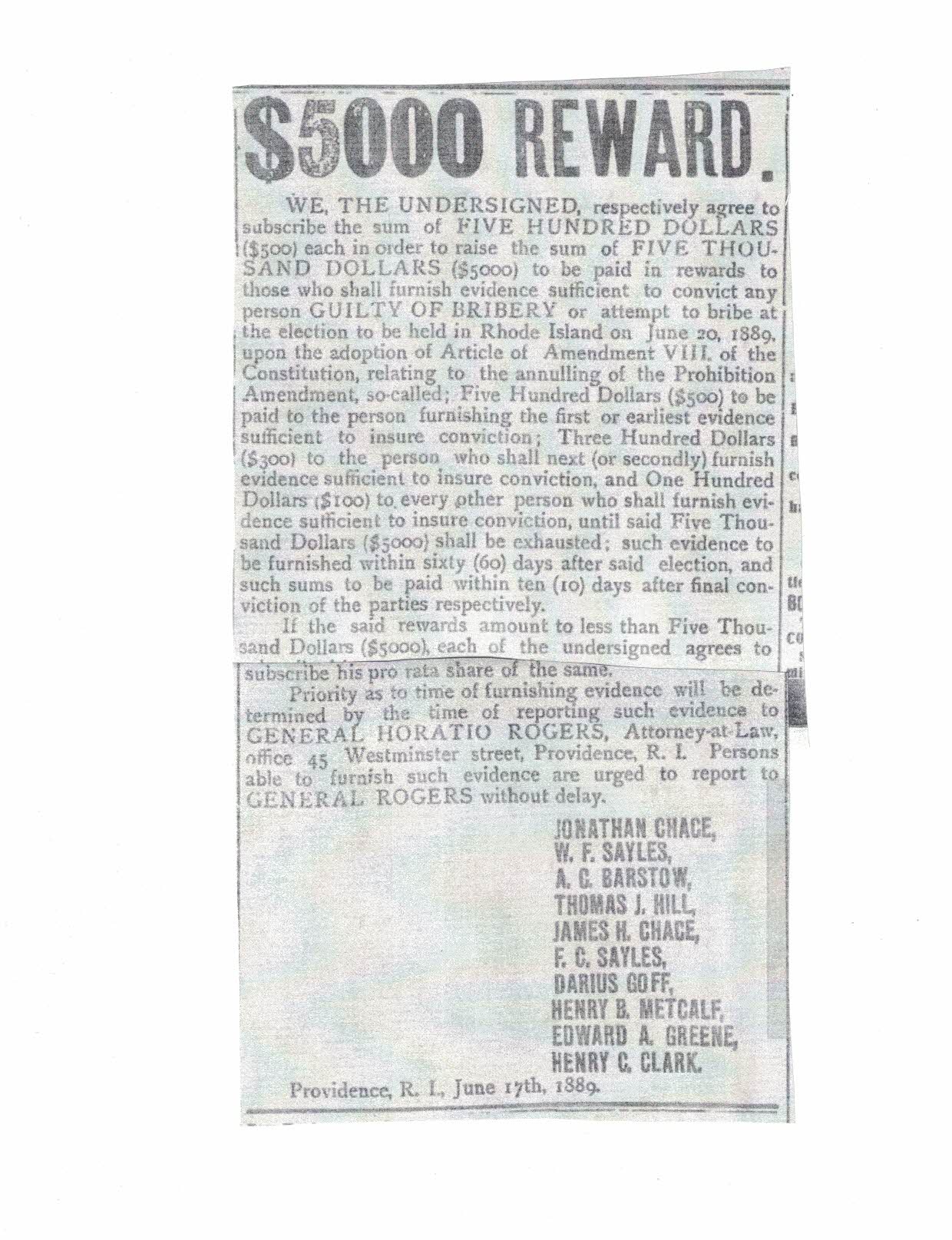

On election day, June 20, newspapers ran ads from parties with opposing views. (See Figures 4 and 5). The ad in Figure 4 noted that three-fourths of the state’s men drink, and the other quarter are either indifferent or lacked the courage to enforce it. Also running the same day was a notice offering a reward of $5,000 to be paid to those offering evidence sufficient to convict anyone guilty of bribery. In reality most elections in Rhode Island were froth with bribery but with so much at stake it is likely the liquor lobby would be spending freely to buy votes.

Of interest, the reward notice in Figure 5 was signed by James H. Chace, recent Law Enforcement Party candidate for governor; Edward A Greene, recent candidate for General Treasurer; and Henry H. Metcalf, chairman of the Law Enforcement Party’s convention the previous March.

Reward notice issued by individuals opposed to annulment (Manufacturers and Farmers Journal, June 20, 1889)

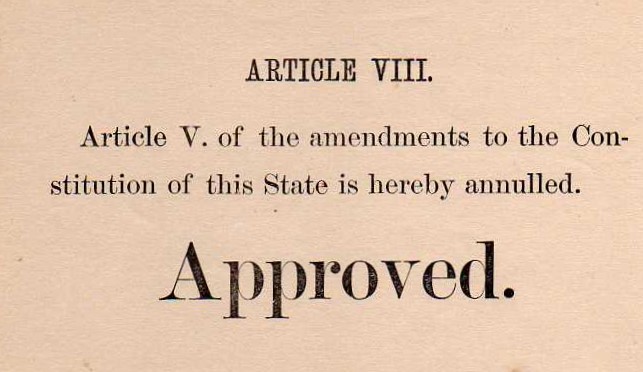

When the election was over and the ballots counted the contest was not even close. (See Figure 6) A total of 28,310 votes were cast in favor of annulment and only 9,956 votes against annulment. A remarkable 74% of those who voted favored repeal making the newspaper’s claim on election day that three out of four men favored repeal a most accurate statement. In the aftermath of the election a special session of the legislature was called and a new license law was enacted.

Conclusion

Sadly, the pushback on prohibition reform in the 19th century in Rhode Island (as well as the rest of the country) often proved violent. As evidenced by the murder of Burrill Arnold of Warwick in 1859 and the attempt on the lives of Reverend Still and Samuel Allen in East Greenwich in 1888, the pro-liquor faction was powerful and would resort to intimidation if need be. They stood to lose lots of money if prohibition prevailed. Surely if the pro-liquor faction would resort to crimes of violence and murder it stands to reason that the lesser crime of bribery would also be used. The failure of the General Assembly and local governments to enforce existing laws must, to a degree, be attributed to the liberal dispensing of money to influence party bosses, law makers and law enforcers. While it is evident the liquor traffic generated lots of money, some of which could be applied to bribe those in politics and law enforcement positions, by contrast, the prohibitionists generated no revenue and could only resort to moral suasion. Money trumped morality.

In addition, the law was unpopular. The 1889 election resulted in an overwhelming majority of adult men (women could not yet vote) voting in favor of repealing the prohibition amendment to the state’s constitution. The results clearly demonstrated that the adult males in Rhode Island were not in favor of state sanctioned prohibition.

In a sense the experiment with prohibition in Rhode Island during the 1880s foretold the experiment with prohibition in the United States in the early part of the 20th century, thus proving that history often repeats itself.[14] The 18th Amendment to the United States constitution of 1919 declared the production, transport, and sale of intoxicating liquors illegal. Yet it took the Volstead Act, passed by Congress the following, year to provide the clout needed for federal enforcement of the 18th amendment to be effective. By comparison, the Law Enforcement Party never had the benefit of a Volstead-like act for Rhode Island in 1889.

Rhode Island never ratified the 18th amendment, one of two states not to do so (Connecticut was the other). Perhaps it learned from experience not to venture into prohibition. When it came time to repeal the 18th amendment, Rhode Island was the third state in the nation to ratify the 21st amendment on May 8, 1933.

Endnotes

- A license ticket appeared as early as 1847. In the statewide election that year Willard Hazard ran for governor and Isaiah Crooker for lieutenant governor. This ticket received few votes. It did demonstrate, however, a growing support favoring temperance reform.

- The law provided anyone convicted the first or second time of selling or suffering to be sold any spiritous or intoxicating liquors forfeiture and a fine of twenty dollars. Subsequent convictions included a jail sentence of not less than three months nor more than six months in addition to forfeiture and a twenty dollar fine.

- Ultimately the proviso requiring a popular vote on the question of repealing a statue was declared illegal. See John H. Stiness, Two Centuries of Rhode Island Legislation Against Strong Drink (1882), p.35.

- During the state’s second experiment with prohibition, one newspaper account referred to a “spirit of terrorism” exercised by the pro-liquor faction. See Providence Journal, March 4, 1887.

- Providence Journal, May 30, 1859.

- Manufacturers and Farmers Journal, April 6, 1874.

- Stiness, Two Centuries of Rhode Island Legislation, p. 49.

- Providence Journal, April 9, 1886.

- See Edward Field, State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations at the End of the Century: A History, vol. 1 (1902), chapter XXII.

- East Greenwich was not exceptional in its voting preferences. During the 1880s, its total vote count was 5% or less for the Prohibition Party’s candidate for governor. The only exception being in 1885 and 1886, at the height of the popularity of the Prohibition Party statewide, when the town cast 11.5% and 17.9%, respectively, of its vote for the Prohibition candidate.

- Providence Evening Telegram, March 23, 1889.

- The party’s banner was inscribed with the words of the newly elected president, Benjamin Harrison: “As a citizen may not elect what laws he will obey, neither may the executive elect which he will enforce.”

- Pawtucket Evening Times, March 29, 1889.

- For a full account of legislation in Rhode Island regarding liquor laws see Stiness, Two Centuries of Rhode Island Legislation, passim.