[From the Editor: John K. Robertson, a retired colonel in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers who holds a PhD., has just released his second reference book on Rhode Island in the American Revolution. This one, Revolutionary War Defenses in Rhode Island (Rhode Island Publications Society, 2022), contains almost 300 maps and plans (nine maps in color) showing defensive fortifications along most of the entire coastline of Narragansett Bay and southern Rhode Island. Many of the maps are of fortifications on Aquidneck Island, which was occupied during the Revolutionary War at various times by the Americans, British and French. In many cases, a British fort replaced an American fort and was replaced in turn by a French fort. But fortifications are shown in virtually all towns on the Rhode Island coastline, including Providence, Bristol, Barrington, Narragansett, and Westerly. This book updates Edward Field’s and George Cullum’s works on Rhode Island fortifications published in the late 1800s—and is more complete and accurate. This attractive coffee-table sized book was published by the Rhode Island Publications Society, which has it for sale online at the reasonable price of $39.95. You can purchase it online by clicking here: https://www.ripublications.org/selected-titles/revwar-defenses-ri/.

The following are questions I posed to Robertson (in bold type) and his responses (in regular type).]

What made you think of making a Rhode Island Revolutionary War book on the maps of the defenses of Rhode Island?

I keep my notes in Evernote, a digital database. Most of my database is chronological, but I also set up a note for each fort. Evernote allows linking notes, so whenever I captured a letter or diary entry that mentioned a fort, I linked it to the fort notes, allowing me link to all the referrals from the fort notes. Evernote also allowed graphics, so I was able to capture images. After a while I realized I knew a lot about many forts. But the tipping point was when I visited the William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan in 2019 and found out that it held many of the maps and plans that I needed, that they were digitized, and that the Library considered them to be in the public domain.

What were your biggest challenges?

Organizing the book and finding where I stored notes (I was not a rigorous crosslinker). In addition, the process of laying out each page of the book took almost a year after the text was finished. Sizing images and keeping images near the text that referred to them was challenging.

What were the biggest surprises in preparing and completing your book?

The biggest surprise was lack of paper to print the book. We had the book laid out in December 2021, but it was not until August 2022 that the acid-free paper was available.

Authors often have to go out-of-pocket to pay for images for their books. Did you have to spend much money out-of-pocket to obtain rights to use some maps?

No. I chose to use maps and aerial photos/satellite images in the public domain. The location maps in Chapters 13 through 16 became excerpts from U.S. Geological Survey quadrangles because it was not clear I could use Google Maps without violating copyright rules. Fortunately, I did not have to leave out any maps I wanted to use in the book.

Deciding how to structure a book is often one of the biggest challenges in writing a book. How did you decide to structure the book?

The first decision was to make it a reference book, designed to look up a particular fort or location; it is not designed to be read as a narrative story or in its entirety. The two obvious ways of organizing the book were chronologically or geographically. Chronologically would have had the reader jumping all throughout the book looking for maps related to a single fortification. Since most of the forts and actions were on Aquidneck, I started there and then filled in from north to south. So for each geographic area, the book goes from north to south. There is a chronological list in Appendix A, cross referenced to the appropriate text location.

Why are some of the maps and plans placed sideways and upside down?

During the period of the war, there appear to be no mapping standards or conventions. Maps today are almost always oriented with north at the top of the page. That is something readers are used to and comfortable with. I rarely provide a single map of a fort, and to get the most out of the book, the reader needs to be comparing these maps. Since the maps had no common orientation, I chose to use the modern convention of north at the top of the page to allow easy comparison (except in Appendix B, where maps were oriented to get the biggest copy we could get on the page).

It should be of interest to many Rhode Islanders that you cover the defenses of many areas of Rhode Island, and not just the obvious locations of Aquidneck Island and Providence. For example, Warwick, Barrington, and Westerly are covered. Was that intentional?

My main sources were, in chronological order of publication: George W. Cullum, Historical Sketch of the Fortification Defenses of Narragansett Bay since the Founding, in 1638, of the Colony of Rhode Island (Washington, D.C.: privately printed, 1884) Edward Field, Revolutionary Defenses in Rhode Island (Providence: Preston and Rounds, 1896); D. K. Abbas, Rhode Island in the Revolution: Big Happenings in the Smallest Colony, 4 vols., 2nd ed. (USDI National Park Service, American Battlefield Protection Program, 2006); and Peter and Phil Payette, “North American Forts, 1526 – 1956,” online website at www.northamericanforts.com. They all covered the complete state of Rhode Island along its shores, so I followed their leads.

What do you think is the most important insights provided by your book?

That the British felt that its Navy protected the western shore of Aquidneck Island until the Navy burned almost all of its ships in August 1778 (they built no forts there except when the French arrived). And that the British army could not secure the whole of Aquidneck against an American army but could withdraw into its fortified lines and defend against an attack until reinforcements arrived.

“A topographical chart of the bay of Narragansett . . . .” Made in 1777 by Charles Blaskowitz. The map was made by the British after British army and navy forces seized Aquidneck Island and Conanicut Island (Jamestown) in December 1776. The map shows some defensive works and batteries prepared by Rhode Island forces (Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division).

A new and active organization has arisen centered on the restoration of Butts Hill Fort in Portsmouth, The Battle of Rhode Island Association. Did you find anything new about it and its role in doing your book?

Everything I found is in readily available sources. The orderly books from the Massachusetts militia that cover the daily routine of the regiments that built the French version of the Butt’s Hill fort sheds light. And the material on Turner’s regiment in 1781 is of interest, but I do not know whether those sources are new.

Kenneth Walsh was the driving force behind an excellent study on the siege of Rhode Island for the Middletown Historical Society. Was that a useful source for you?

I have used the Middletown Historical Society study that Ken chaired. I am sorry I never got to meet him before he passed away in 2019. I have read the study and agree with its conclusions.

What were some of the most useful published sources you relied on for your book?

The Diary of Lt. Frederick Mackenzie, 23rd (Royal Welch Fusiliers) Foot (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1926). So much of what we know about the British occupation of Rhode Island comes from him.

Christian McBurney, The Rhode Island Campaign: The First French and American Operation of the Revolutionary War (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2014), provided a lot of background and leads.

Original diaries of participants. I wish there were more, particularly American.

While not published, the Norman B. Leventhal Map and Education Center at the Boston Public Library is a treasure trove of old maps.

I imagine many of the maps were in gorgeous color, but that it was not possible for the publisher to afford to print them inside the book in color?

While there are many important maps in color in Appendix B, we were not able to make them all in color. Even though this was a large format book, it is not big enough to do many of the maps in the appendix justice. That is why there are so many excerpts of maps in the book: we needed to show the locations at a size that is readable. The book does provide information on how to obtain digital copies of the maps.

Were you pleased that the Rhode Island Publications Society agreed to publish your book?

Yes. What I really like is their commitment to putting the history of Rhode Island in the hands of the citizens by publishing Rhode Island history books and then distributing free copies to the public libraries in the state. When I met with Dr. Patrick T. Conley in 2018, I explained to him that I was interested in writing a history of Rhode Island during the American Revolution, but that I needed first to publish three reference books: a transcription of the Proceedings of the Council of War and its predecessor, the Recess Committee; a book on the fortifications of Rhode Island; and a book on the units that served in the state. The first was published by the Rhode Island Publications Society in 2020 (Proceedings of the “Recess” Committee of the Rhode-Island General Assembly 1775-1776 and the Rhode-Island Council of War 1776-1782); the second is the book on Rhode Island fortifications that is the subject of this article, which was published by the Rhode Island Publications Society in October 2022; and the third, to be called Defenders of Rhode Island, is about 80 percent complete and hopefully will be published by 2024. The history of Rhode Island during the American Revolution exists in my notes in outline form and in small essays. I hope to complete the writing and have the Rhode Island Publications Society publish it for the 250th anniversary of the American Revolution, probably in 2026. I also hope to publish transcriptions of the many orderly books I have used in these studies.

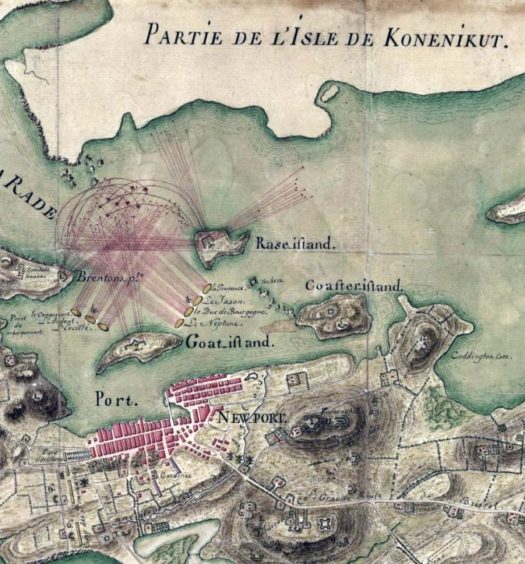

“Plan de la ville, port, et rade de Newport ….” From 1780 made by French army engineers. The map shows the defensive plan for Newport and its environs after the French occupied it in July 1780. The French feared a British invasion would occur shortly after the French landings. The British made some plans for such an invasion, but it did not occur (Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division)