[Note from the authors: The essay that follows is a condensed version of a longer essay that is to accompany a major addition to the Dorr Rebellion Project (at http://library.providence.edu/dorr/) that addresses the Gag Rule in the U.S. Congress. Research for this effort was underwritten in part by a grant from the Rhode Island Foundation.]

In 1836, the U.S. Congress adopted rules automatically tabling all petitions relating to slavery in an attempt to shut off all floor debate hostile to the South’s peculiar institution. However, the gags only served to embolden antislavery politicians. Despite the efforts of southern Congressmen, Congress continued to be flooded by reams of paper protesting the federal government’s connection to slavery. The principal vehicles for attacks on the gags were petitions opposing the annexation of Texas, slavery in the federal territories and the District of Columbia, and the admission of new slave states. Antislavery politicians both in Washington and at the state-level raised issues relating to freedom of press, speech, and the right of petition to challenge the gags. The debate in Rhode Island over the gag was intense and led to the political emergence of one of the important figures in the state’s history—Thomas Wilson Dorr.

After a year of practicing law in New York City, Thomas Wilson Dorr returned to his native Providence in 1832 and embarked on a course to modernize the political structure of Rhode Island. The political reform movement that had begun to sweep the country in the 1820s and fundamentally reorient the nation’s political landscape created the political and societal background for reform efforts.

Though Thomas Dorr is most famously known for the short-lived rebellion in 1842 that bears his name, leading a revolt against the legal authorities of his native state was the farthest thing from his mind when he entered politics in the spring of 1834. From the start of his political career, Dorr was connected with a third-party effort comprised of middle-class reformers. Dorr’s idealism and zeal brought him immediately into conflict with veteran, conservative legislators.

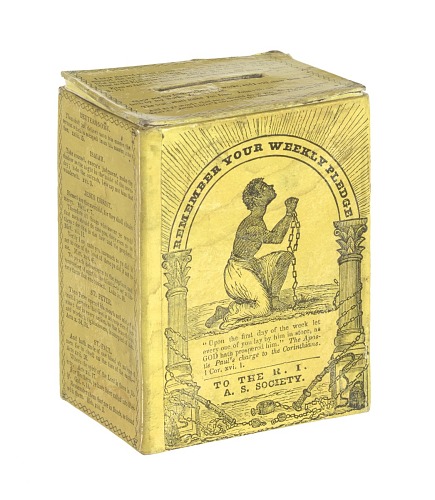

Collection box for the Rhode Island Antislavery Society (Smithsonian Institute, Museum of African American History)

In his early days in the General Assembly, the freshman legislator entered a heated multi-day debate with the veteran Benjamin Hazard (1774-1841), a Newport Whig, on the nature of political reform. By the time of the debates, Hazard was a seasoned politician having served as a state representative from Newport since 1809 and twice serving as Speaker of the House. Hazard was an old school Whig having started out as a Federalist and even having participated in the Harford Convention in 1814. According to the young and somewhat brash Dorr, Hazard’s difficulty with political reform lay deeper. It was the “dread of personal consequences” that in Dorr’s mind made “some men cling with such a desperate grasp, strengthened by the energy of self-preservation, to the decaying remnants of the present fabric.”[1]

During his first term in the legislature, Dorr attempted multifaceted reforms from within the ranks of a small group of “New School Whigs” in Rhode Island who were not dismayed by the democratic revolutions of the antebellum period.[2] He championed numerous reform causes — public education, freedom of speech, banking, suffrage extension, imprisonment for debt, and prison reform.

Antislavery Efforts on the Rise

Thomas Dorr also promoted antislavery efforts. In 1835, Dorr, an abolitionist who would later serve on the executive committee of the Rhode Island Antislavery Society, entered into a pitched battle to protect the freedom of speech and assembly for New England abolitionists. His opponent was once again his new nemesis, Newport’s Benjamin Hazard.

The goal of abolitionists was to convert slaveholders by appealing to their sense of righteousness and justice, a strategy known as moral suasion.[3] These dedicated reformers insisted that the moral question be kept at the front and center of public debate. Debates over the continued presence of slavery in the United States had accompanied the constitutional convention in 1787 and the ratification debates, federal statutes opposing the slave trade that led to congressional prohibition of the slave trade in 1808, and the intense congressional debate over the admission of Missouri to the Union.[4] However, by the 1830s, abolitionists and antislavery activism entered a new phase marked by a high-level of intensity.

In 1835, the newly formed American Antislavery Society (AASS), headquartered in New York City, set out to mail to residents of southern states 175,000 items describing the evils of the institution of human bondage.[5] Founded in 1833, in the wake of the British Parliament’s vote to outlaw slavery in its West Indian colonies, the AASS doubled in size in just a few years, with a roster of more than five hundred local auxiliaries in fifteen states.[6]

In 1837, the AASS established an agency in the nation’s capital. The coinciding rise of changes in printing techniques that enabled publishers to distribute illustrated materials at reduced rates helped to spread the abolitionist message.[7] By 1837, over 300,000 petitions had been sent covering the antislavery spectrum: 130,000 for the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia; 182,000 against the annexation of Texas; 32,000 for the repeal of the gag rule; 21,000 for legislation forbidding slavery in territories; 23,000 for abolition of the interstate slave trade; and 22,000 against the admission of any new slave state.[8]

The Gag Rule and the U.S. Congress

On December 18, 1835, a petition submitted to the U.S. Congress calling for the abolition of slavery in D.C. from citizens of Cummington, Massachusetts, a small town in the western part of the state near the New York border, caused a stir on the floor of the House. After much back and forth on December 18 and 23, the petition was ultimately squashed.

There were varying degrees of antislavery sentiment on the anti-gag spectrum. Former president and now U.S. Representative from Massachusetts, John Quincy Adams, wholeheartedly believed that the gag rule was unconstitutional, but in terms of whether or not Adams wanted to see Congress take up abolition in the capital that was another story. He told the House that he did not support abolishing slavery in Washington, D.C. In a letter to Alexander Hayward, a Coventry, Rhode Island, abolitionist, Adams wrote, “I do not think it just or generous that you should be the Petitioner to impair their right of property and not your own. The Inhabitants of the District of Columbia have a right to petition the Legislature of Rhode Island to pass a law for taxing you and your estate, what would you think of such a petition?”[9] The Rhode Island Whig delegation of Dutee Pearce and William Sprague, Jr. sided with Adams on the point that a gag was unconstitutional.

South Carolina Congressman James Henry Hammond demanded that abolitionist petitions, which had been flooding into the corridors of power in Washington for months, be discarded with no recognition given. Hammond would later coin the phrase “cotton is king.”

In a speech in early 1836, Hammond gave a detailed overview that clearly demonstrated the impact of the abolitionist campaign, including mention of the Rhode Island Anti-Slavery Society and signatures from residents of Pawtucket.[10] Indeed, the opening third of his floor speech covered the history of Garrisonian radical abolitionists from 1831-1835. However, abolitionist doctrines, according to Hammond, could only lead to a “bloody” and “exterminating” war in the country between whites and Blacks. Hammond justified the gag rule on the ground that in demanding abolition in the nation’s capital abolitionists were asking Congress to pass a law that would violate a slaveholders’ rights of property.[11]

Another South Carolinian, Henry Laurens Pinckney, a man with political ambitions to be included as the number two choice on Vice President Martin Van Buren’s ticket for the presidency in 1836, proposed in an effort to tamp down Hammond’s hard-liner position that Congress send all abolitionist petitions to a select committee of which he was in charge.[12] The Pinckney committee returned in May with a three-pronged report that included proposals calling for the public acceptance of the principle that Congress possessed “no constitutional authority to interfere, in any way, with the institution of slavery in any of the states of this confederacy.” Congress “ought” not to interfere with slavery in the District of Columbia. And, finally, the all-important third resolution: all “petitions, memorials, resolutions, propositions or papers, relating in any way, and to any extent whatsoever, to the subject of slavery, or the abolition of slavery, shall, without being printed or referred, be laid upon the table, and that no further action whatever shall be had thereon.”[13]

Only nine members of the House, including John Quincy Adams (but none from the Rhode Island delegation), voiced opposition to Pinckney’s first resolution about the inability of Congress to act upon slavery in the states. While Adams was given no room to speak, not a mere “five minutes,” as he said, to challenge, he did find a way to make a case the next day in terms of what Congress and the Executive could do in times of war when it came to slavery.[14] Adams’ viewpoints would later provide a blueprint for the Republicans during the Civil War.[15]

Thirty-seven of Adams’ northern Whig colleagues joined him in opposing the non-interference plank Pinckney included as his second resolution, but it too was adopted.[16]

The third proposal, the infamous gag, went into effect with a vote of 117-68 on May 26. When the clerk came to his name in the roll call, John Quincy Adams rose from his seat and boldly declared, “I hold the resolution to be a direct violation of the Constitution of the United States, the rules of this House, and the rights of my constituents.”[17]

Nearly four out of five northern Democrats voted to stifle debate and nine of ten of all southern representatives of both major parties voted in favor of Pinckney’s plan.[18] During the closing arguments over Pinckney’s resolutions, Adams rose in protest, but before he could proceed with a speech, southerners blocked him. “Am I gagged or not?” Adams asked, giving Pinckney’s third resolution its name.[19] Yet, this did not stop abolitionists from circulating their agenda.

In 1840, the House made the gag rule part of its standing operating procedure. This would last until the end of 1844 when it finally came to end in dramatic fashion.[20] On December 3, 1844, the House repealed the gag rule. Adams had the date engraved on the top of his cane. Adams willed the cane to the American people, and it was later transferred from the patent office to the Smithsonian where is still resides today.

In the early years of the gag rule, the vast majority of Democrats in the House, both northern and southern, supported it, while the Whig party was split along sectional lines. In the 1840s, Northern Democrat support for the Gag Rule began to wane. [21] The U.S. Senate gag rule, based on a procedural rule to table the reception of abolitionist petitions, lasted into the 1850s.[22] It was the product of southern fears for the long-term health of slavery and northern desires to avoid a sectional conflict that could destroy the Union.

The Gag Rule Comes to Rhode Island

Not content with forbidding discussion of anti-slavery petitions in the House, the slaveocracy also wanted each northern state to clamp down on anti-slavery organizations. Most northern states received letters addressed to their governors requesting action. Rhode Island was no exception. It received letters from numerous southern states asking for action to outlaw anti-slavery societies and institute a gag rule on its citizens. On the state level, abolitionists petitioned legislatures to challenge the national gag rule and to condemn the actions of slaveholders.[23]

The “Slave Market of America” refers to the selling and purchasing of enslaved people being permitted in Washington, D.C. prior to 1850. This is an anti-slavery broadsheet advocating the end of such sales in the District of Columbia. Congress finally abolished the slave trade in the District of Columbia in September 1850 as part of a legislative package known as the Compromise of 1850 (Library of Congress)

In response, numerous Rhode Island state representatives, including Dr. Silas James, Jr., went to great lengths to condemn what they deemed to be the fanatical spirit of the abolitionists who they believed threatened the sanctity of the Union. In a lengthy, ten-page memorial submitted to the General Assembly and, later, printed as a broadside, James maintained that “no man of sense and in his right mind, can for a moment suppose, that all the efforts of the abolitionists of the North could have the effect to emancipate the slaves of the South.” It was self-evident, according to James, that on the “ill-natured interference” of the abolitionists in relation to the “matter of Southern slavery and their tirades abuse lavished indiscriminately on the slaveholder, would have the direct tendency to excite the angry passions and create a sense of danger which would lead to greater severity, as an act of self-defense.”[24] In James’ analysis, the horrors of southern slavery that were being exposed by the growing abolitionist press were excusable because they simply stemmed from the angry reaction of white slaveholders to perceived threats against their way of life. Therefore, the removal of northern agitation would make the life of the slave better. This was a foolish notion not grounded in contemporary reality but nonetheless it was a view widely shared.

The executive committee of the Rhode Island Antislavery Society, one of the more robust state-level auxiliaries in the North, asked whether this state, “renowned in the annals of other States for its justice to all, its impartial toleration of opinions, and its magnanimous and uniform protection of the freedom of speech and the rights of conscience, shall now be deprived of this precious inheritance?” The committee further inquired whether citizens should be “subjected” to a “servile and mercenary few” intent on the “mean and oppressive purpose of condemning unheard, and injuring in their good name, a large, unoffending, and faithful portion of its citizens, marking them out as standing objects” of the “apologists for American republican slavery.”[25]

In the summer of 1835 at a Newport town council meeting, the topic of abolition societies arose. This precipitated debates on abolition that were to follow in the General Assembly the following year. Newport was at the time a favorite vacation place for many southern plantation owners. Its moderate climate in summer offered a respite from the oppressive summer heat of the South and as such became a summer colony to slaveholding families who were usually accompanied by their domestic slaves. One such southerner, Richard K. Randolph (1781–1849), became a year-round resident when he married Anne Maria Lyman of Newport. Randolph hailed from a prominent slaveholding Virginia family and served in the Rhode Island House of Representatives from 1837 to 1844.[26]

The Newport town council appointed a committee to draft a resolution for presentation to the Rhode Island General Assembly. The committee completed a lengthy report in September 1835. The eleven resolves in the report placed blame on the abolitionists, specifically on the “desperate leaders of the Anti-Slavery Societies who cannot be ignorant of the mischief they are working.” The resolutions, while supposedly developed in committee, have all the markings as coming from the pen of Benjamin Hazard. Hazard was the author of a racist report in 1829 on the extension of suffrage and some of the Newport resolutions were taken verbatim from this earlier report, especially where Hazard questioned whether “the African race who Nature herself has distinguished by indelible marks, and whom the most zealous asserters of their equality admit to be, if not a distinct species, at least a variety of the human species, and all experience has shown us that distinct races, (if we may not say species) of men, can never be so far assimilated as to embrace the same views of common good, or to unite in pursuing the same common objects and interest.”[27]

While all of the Newport resolutions addressed slavery in various ways, including immediate emancipation, colonization in Africa, slave insurrections, the inability of the “Negro” to self-govern, and state rights, it was the ninth resolution that addressed freedom of the press. This resolution noted that freedom of the press would be best “secured by guarding it against such abuses as these abolitionists have prostituted it to … It is not for such bold offenders to appeal to the freedom of the press. The public and the laws will take care of the freedom of the press: and they will take care that it shall not be so abused, with impunity.”[28]

While the Newport petition was the first anti-abolition protest to reach the Rhode Island General Assembly it was not the last. In December 1835, the state of Georgia sent a report and resolution of its legislature addressed to the northern states. The Georgia correspondence was but the first to arrive from slave-holding states. Soon similar correspondence from other slave-holding states followed, including Alabama in January and Kentucky and Mississippi in February. Newspapers reported that on January 28, 1836, on a motion made by Richard Randolph in the state House of Representatives, the communications from the governors of North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia, relative to the proceeding of abolition societies, were presented.[29]

By March, several northern states sent their reports and resolutions concerning the agitation caused by the abolitionists. On March 24, 1836, Maine sent a report with resolutions from its legislature to Rhode Island. An excerpt reads: “Slavery is a question in which we as a state have no interest, it is unknown in Maine, and those States who recognize its existence, have the exclusive control of the subject within their borders. As one of these United States, it is not for Maine, or the citizens of Maine to interfere with the internal regulations of any other Independent State; no possible good can result from such an interference with the affairs over which they can exercise no control.” Ohio and Michigan soon followed with similar resolutions.[30]

Following the formation of the new legislature in May, Dorr, along with four others, was assigned to a committee “to consider and report upon the memorials” of “citizens of the state, relating to the subject of Free Discussion and the Liberty of the Press; and that said committee be directed to hear such testimony as may be directed to them by, or in behalf of the petitioners.”[31] Dorr, an ardent antislavery Whig, was appointed chairman of this committee. At the same session it was enacted that all documents concerning the subject of the abolition of slavery transmitted to the Governor of the state and all other papers now in the files of the House be referred to the committee. In so doing all decisions by the state of Rhode Island would now be addressed in the reports issued by this committee.

The intent was for the committee to meet on the evening of June 22 to consider all the petitions so far received. Dorr, as chairman of the committee, unilaterally placed public notice announcements in local newspapers as early as mid-May announcing the scheduled meeting and suggesting that those memorialists in attendance would be heard. As such the AASS looked to its public lecturers to go to Newport and present before the committee. Of concern to the abolitionists was a proposed bill introduced by Benjamin Hazard in January providing that “all overt acts and practices calculated and designed to incite the slaves in the slaveholding states against their masters encouraging them to insurrection, and thereby endangering the property, safety and lives of the people of those states should be deemed to be criminal offences and punished, etc.”[32]

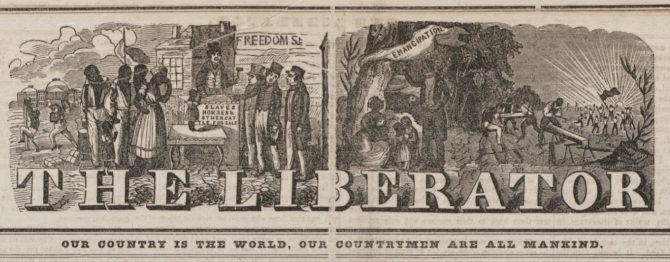

The 1838 masthead of The Liberator, an antislavery newspaper published by William Lloyd Garrison from Boston (Boston Public Library)

Nonetheless, a protracted debate began in the House of Representatives that afternoon pitting arch-conservative Hazard against the liberal-minded Dorr and others. The debate revolved on the question of whether or not representatives of the abolition movement would be allowed to testify in person at the evening committee hearing. The Rhode Island Anti-Slavery Society brought in some of the best agents to make an oral argument, including William Lloyd Garrison, but to no avail. After much discussion, the subject was tabled, and the committee meeting scheduled for that evening canceled. Precluded from making their case in person many of the anti-slavery newspapers presented the AASS case in print as an address titled To the People of Rhode Island. “What, in the third century of liberty in this state, I am ashamed to know that is refused to hear an application which is a proper one,” maintained Dorr on the floor of the House.

The debates in the General Assembly in 1836 did not place a gag rule on abolition petitions, as was the case in the U.S. Congress, since the Rhode Island House received few such anti-slavery petitions. Petitions and memorials that were received were mainly from anti-abolitionists complaining about the threat of disunion created by abolitionist writings. What the Rhode Island House did do was to deny representatives of anti-slavery societies from appearing in person to give testimony before the committee charged with hearing such matters. In that sense it did curtail legislative discussion on the issue of slavery. However, as proclaimed in the newspaper Rhode Island Republican on August 23, 1837 “In the land of Roger Williams no barrier should ever be raised against Free Discussion.”

The verbal exchange of words and ideas between the young Thomas Dorr and the much older Benjamin Hazard in 1836 was more than a generational spat. Dorr was indeed new to the General Assembly in 1836, while Hazard had been a state representative for a quarter of a century before Dorr was first elected in 1834. However, significant philosophical differences between the two men played out in the exchange of words on the floor of the House of Representatives on a variety of topics. As shown in this essay, Hazard’s strong dislike of abolitionists may in part have been due to the fact that Richard Randolph, a fellow Newporter, state representative, and member of the slaveholding Virginia Randolph clan, was his brother-in-law. Still, Hazard was against change of any kind. Not only did he have racists beliefs about Blacks (free or enslaved), he also strongly objected to immigrants and non-Rhode Island born residents. At one point he even suggested that those who disliked the way things were in Rhode Island were free to leave the state. Two time Speaker of the House Hazard was a powerful politician and accustomed to getting his way in House deliberations.

Dorr was a gifted young lawyer. After having graduated from Harvard University, he studied law under James Kent, the Chancellor of New York State, before returning to Rhode Island. Coming from an affluent family it was not too surprising that he started out his political career as a Whig. Over time Dorr’s liberal way of thinking often caused him to clash with Hazard. These clashes occurred not only in House debate but in the constitutional convention that was held in 1834. The topic of debate may have varied but the great univariable was Hazard resisted reform measures and Dorr advocated for them. The debates between the two men lasted until Hazard’s death in March 1841. There is little doubt that had he lived, Hazard would have been one of the loudest opponents of Thomas Dorr and the Rhode Island Suffrage Association in 1841-42.

Notes

[1] Manufacturers’ and Farmers’ Journal, September 3, 1834. [2] On “New School Whigs,” see Sean Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln (New York: W.W. Norton, 2005), 483. [3] For overviews of the abolitionist movement, see James Brewer Stewart, Holy Warriors: The Abolitionists and American Slavery, rev. ed. (New York: Hill and Wang, 1996) and Manisha Sinha, The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016). [4] The best treatment of early antislavery political and constitutional thought remains William M. Wiecek, The Sources of Antislavery Constitutionalism, 1760-1848 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1977). See also the essays in John Craig Hammond and Matthew Mason, eds., Contesting Slavery: The Politics of Bondage and Freedom in the New American Nation (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2011) and Matthew Mason, Slavery and Politics in the Early American Republic (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006). [5] Corey M. Brooks, Liberty and Power: Antislavery Third Parties and the Transformation of American Politics (Chicago, Il.: The University of Chicago Press, 2016), 17. See also Leonard L. Richards, The Slave Power: The Free North and Southern Domination, 1780-1860 (Baton Rouge, La: Louisiana State University Press, 2000), 136-137. [6] Henry Mayer, All on Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998), 217. [7] For a detailed overview see the following entry from the British Library: https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/print-culture [8] David C. Frederick, “John Quincy Adams, Slavery, and the Disappearance of the Right of Petition,” Law and History Review 9:1 (Spring 1991), 132. [9] Quoted in Frederick, “John Quincy Adams, Slavery, and the Disappearance of the Right of Petition,” note 69, page 150. [10] See speech set forth on the following on page 7: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hx4q2m&view=1up&seq=11For more on the Rhode Island Antislavery Society. see John Myers, “Antislavery Agents in Rhode Island, 1835-1837,” Rhode Island History (Winter 1971), 21-32 (at https://www.rihs.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/1971_Jan.pdf) and Deborah Bingham Van Broekhoven, The Devotion of These Women: Rhode Island in the Antislavery Network (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2002).

[11] This property-rights argument would be countered by Theodore Dwight Weld in his pamphlet, The Power of Congress over Slavery in the District of Columbia (1838). [12] See Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848 (London: Oxford University Press, 2007), 509-512. [13] Register of Debates, 24th Congress, 1st Session (May 18, 1836), pp.3756-3757 and Register of Debates, 24th Congress, 1st Session (May 26, 1836), p.4050. See also William Lee Miller, Arguing About Slavery (New York: Vintage Press, 1998), 144-145. [14] Register of Debates, 24th Congress, 1st Session (May 25, 1836), p.4032, 4046. See also Leonard Richards, The Life and Times of Congressman John Quincy Adams (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), pp.122-123. [15] See James Oakes, Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States 1861-1865 (New York: W.W. Norton, 2012), 348. [16] Richards, The Life and Times of Congressman John Quincy Adams, 124. [17] Journal of the House of Representatives of the United States, 24th Congress, Appendix (May 27, 1836) 1410. [18] Sean Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln, 452. See also Richards, The Life and Times of Congressman John Quincy Adams, 115. [19] Register of Debates, 24th Congress, 1st Session (May 25, 1836), 4030. [20] Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Slaveholding Republic: An Account of the United States Government’s Relations to Slavery (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 77. See James Traub, John Quincy Adams: Militant Spirt (New York: Basic Books, 2016), 507-509 and Miller, Arguing About Slavery, 470-477. See also Adams’ provocative April 1844 speech in the House, which is set forth here: https://digital.library.cornell.edu/catalog/may837614 [21] See Traub, John Quincy Adams, 507-508. [22] See Daniel Wirls, “‘The Only Mode of Avoiding Everlasting Debate’: The Overlooked Senate Gag Rule for Antislavery Petitions,” Journal of the Early Republic 27:1 (Spring, 2007), 115-138. [23] See Kate Masur’s discussion of the petitioning campaigns of state level abolitionist organizations on a wide variety of issues, including the gag rule and discriminatory Black Laws that prevented African Americans from voting or receiving an equal education. Masur, Until Justice Be Done: America’s First Civil Rights Movement, From the Revolution to Reconstruction (New York: W.W. Norton, 2021). [24] James’ petition is housed at the Rhode Island State Archives. A PDF of the original petition, along with a full transcription, can be found at the Dorr Rebellion Project website: http://library.providence.edu/dorr [25] Liberator, July 2, 1836. [26] For more on Randolph, especially during the 1842 Dorr Rebellion in Rhode Island, see Erik J. Chaput and Russell J. DeSimone, “Newport County in the 1842 Dorr Rebellion,” Newport History 83 (2014), 1-31 (also available at https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/newporthistory/vol83/iss271/2). [27] See “Report of the Committee on the Subject of an Extension of Suffrage,” (1829), 20–21. Rhode Island State Archives. [28] Rhode Island Republican, September 16, 1835. The quote is taken from the ninth resolution of the Newport Town council petition. [29] Herald of the Times, February 4, 1836. [30] Rhode Island State Archives files relating to 1836 Abolition petitions, see Folder #6: Maine; Folder #7: Michigan; and Folder #12: Ohio. Special thanks to archivist Ken Carlson for help locating these petitions. [31] Providence Journal, June 24, 1836. The committee was, in addition to Dorr, comprised of Joseph M. Blake of Bristol, George W. Gavitt of Westerly, Benjamin Hazard of Newport and Thomas T. Hazard of West Greenwich. [32] Rhode Island Republican, July 6, 1836.