While writing of the diversity of religious leanings in the colony of Rhode Island for my recent book on colonial New England (see the advertisement next to this article), I came across Samuel Gorton, perhaps one of the most complex men in our state’s early history. While he was in almost constant conflict with Roger Williams, or any with authority for that matter, he was also beloved by his followers and a friend to local Native Americans. Despite his conflicts with the colony’s founder, he was chosen to serve as assistant to President John Smith of Warwick in the early days of the General Assembly. Both Gorton and Smith initially refused to serve in the new government, but under the threat of penalty of fines they relented, launching Gorton on a career of public service that eventually overshadowed his earlier reputation. He was chosen President of the Colony in 1651, but shared power with William Coddington who overlooked Newport and Aquidneck, while Gorton tended to affairs in Warwick and Providence.

Early Rhode Island historian Samuel G. Arnold would write of Samuel Gorton, “He was one of the most remarkable men that ever lived. His career furnishes an apt illustration of radicalism in action, which may spring from ultra-conservatism in theory. The turbulence of his earlier history was the result of a disregard for existing law, because it was not based upon what he held to be the only legitimate source of power—the assent of the supreme authority in England. He denied the right of a people to self-government, and contended for his views with the vigor of an unrivalled intellect and the strength of an ungoverned passion. But when this point was conceded, by the securing of a Patent, no man was more submissive to delegated law. His astuteness of mind and his Biblical learning made him a formidable opponent of the Puritan hierarchy, while his ardent love of liberty, when it was once guaranteed, caused him to embrace with fervor the principles that gave origin to Rhode Island.”

Gorton and his followers believed in the simple premise that the spirit of God, or the “holy Spirit” was present in all people whether they be sinner or saint. A religious conversion meant that one was following the dictates of one’s own divinity, even against the present law and authority.[1] One of his followers, and the subject of this article, John Angell, told Ezra Stiles, pastor of the First Congregational Church in Newport, that Gorton had routinely walked in the woods to hear the divine voice through nature, an act in such times that would surely have raised the ire of the Puritans who did not believe in such practices. As a community, however, the Gortonists succeeded to a large degree. The followers had no church, but a meeting house in which they met regularly. They held no organized congregation, declared no religious edicts, or tolerated any association between secular and religious concerns.[2]

In the aftermath of Gorton’s death in 1677, most of his followers joined Quaker or Baptist communities. As historian Sidney V. James phrased it, “His personality proved in the end, to be the sole source of unity.”[3] But not every Gortonist, or Gortonite (as more recent historians have called them), joined another church or changed their beliefs. Some carried on Gorton’s theology well after any living memory of the man had faded. The first encounter with the person who is widely believed to have been the last Gortonist is recorded in the Itinerarium of Dr. Alexander Hamilton, the journal of a Scottish physician’s travels along the east coast of the colonies in 1744.

Hamilton had just crossed the Pawtucket Falls, where his horse had been spooked by the rushing water, and he had to lead it across the wooden bridge above the falls. Horse and rider continued south along the Post Road until reaching Providence, of which he would write: “I breakfasted in Providence att one Angel’s at the sign of the White Horse, a queer, pragmaticall old fellow, pretending to great correctness of stile in his common discourse. I found this fellow at the door and asked him if the house was not kept by one Angel. He answered in a surly manner “no”. “Pardon me” says I, “they recommended me to such a house”. So as I turned away: being loath to lose his customer, he called me back. “Hark ye friend,” says he in the same blunt manner, “Angell don’t keep the house, but the house keeps Angell.” I hesitated for some time if I should give this surly chap my customer but resolved att last to reap some entertainment from the oddity of the fellow. While I waited for the chocolate which I had ordered for breakfast, Angell gave me an account of his religion and opinions, which I found were as much out of the common road as the man himself.”[4]

In trying to ascertain the identity of this tavern keeper, Carl Bridenbaugh, the editor of the Itinerarium, notes the records of one Joseph Angell paying “the highest” license fees in Providence in 1749 and 1750. In addition, we find within Jane Lancaster’s “Inquire Within,” the story of the men working to establish a library in Providence: “During the summer and fall of 1753, Stephen Hopkins and his friends gathered names of potential subscribers, and by December 15 they had enough to make the Library Company viable. Nicholas Brown, Nicholas Tillinghast, and John Randal were then authorized to collect the subscriptions . . . . [T]he group met on Christmas Day at the house of Joseph Angell (on Towne Street near where Angell Street now begins).”[5]

Four years later, Bayles recorded in his History of Providence County, “The ‘Sign of the White Horse’ was kept by genial Captain Adams and his son, on North Main Street, just opposite the First Baptist church, and it was a great resort for mariners and merchants. Here all the marine news was learned and discussed, and its popularity kept pace with the times. It remained a tavern until 1825 or 1830; then was used as a dwelling; a portion for a museum was later annexed to the Earl House, and finally was absorbed by the Gorham Manufacturing Company.” Bayles also noted that around the same period, “The Pardon and John Angell and Fox taverns were located farther down, the latter down to Knight Street.”[6] John Angell’s house would have been to the southwest, and across the river from the land he and his brother owned above Main Street—“Angell Lane” was still a dirt path running uphill beside the orchard.

It is not clear which brother Alexander Hamilton encountered, bit it would seem to be John, who was visited by the reverend Ezra Stiles nearly thirty years later. “At Providence, Nov. 18th, 1771, I visited a Mr. Angell, aged eighty, born Oct. 18th, 1691, a plain, blunt spoken man, of right old English frankness. He is not a Quaker, nor Baptist, nor Presbyterian, but a Gortonist, and the only one I have seen. Gorton lives now only in him, his only disciple left. He says, he knew of no other, and that he is alone. He gave me an account of Gorton’s disciples, first and last, and showed me some of Gorton’s printed books and some of his manuscripts. He said Gorton wrote in Heaven, and no one can understand his writings but those who live in Heaven, while on earth . . . . He told me his grandfather Thomas Angell, came from Salem to Providence with Roger Williams, that Gorton did not agree with Roger Williams, who was for outward ordinances to be set up again by new Apostles.”

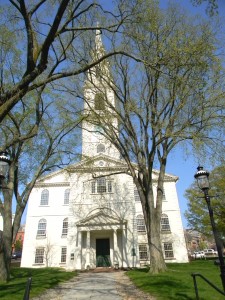

The First Baptist Church of Providence, Rhode Island. It was the first Baptist church, founded in 1638. The meetinghouse was completed in 1775. (Robert A. Geake)

Angell told Stiles that Gorton’s beliefs were not to be compared to those of the Quakers simply for rejecting outward ordinances, but that “Gorton was far beyond them” on that “highway up to the dispensation of light.” “He said Gorton was a holy man, wept day and night for the sins and blindness of the world—his eyes were a fountain of tears and always full of tears, a man full of thought and study, had a long walk out through the trees and woods by his house, where he constantly walked morning and evening, and even in the depth of night alone by himself, for contemplation and enjoyment of the dispensation of light. He was universally beloved by all his neighbors, and the Indians, who esteemed him not only as a friend, but one high in communion with God in Heaven and indeed he lived in Heaven.”[7]

The man Stiles met was John Angell, born October 5, 1691, the son of James and Abigail, the brother of Joseph Angell (1694-1759), and the grandson of Thomas Angell. The brothers are mentioned in a deed of 1722, with John selling Joseph a 1twelve-acre parcel of land in Providence, a corner of which abutted the “highway to Moshantituck” (Cranston Street). The acre upon which that corner sat, was eventually sold to Obadiah Brown, founder of the later famous Hoyle’s Tavern.[8] John also bought the farm whose lands included the historic Clemence –Irons house in 1740. This may well be the place where he was visited by Stiles. The Angell family owned it for several generations but did not reside there. It was mostly tenanted out, but John Angell’s grandson tilled the land and kept the farm until his death.

Joseph was listed as a merchant in Providence, and a licensed tavern-keeper by 1734, an establishment most likely run within his own house. The house may have been the “general store” that his grandfather had established. John was listed as a weaver, but as early as 1756, bookseller James Green was advertising his business as “at the sign of the angel, across from John Angell’s.” After Joseph died on March 21, 1759, it is possible that by this date John taken over his brother’s concerns, which may have included the tavern mentioned in Bayle’s history.

Another note in the long chapter of John Angell’s long life comes to us as the town was determining the place to build a new Baptist meeting house. As recorded in Gertrude Kimball’s Providence in Colonial Times, “the lot selected for the new meeting house was then an orchard belonging to John Angell, who is credited with being the last of the Gortonists, who at all events was no admirer of the Baptist theology. It was felt, and doubtless with good reason, that Mr. Angell would be violently opposed to selling his property as a site for a Baptist meeting house. In this dilemma . . . good William Russell, a pillar of the Episcopal church was induced to negotiate the purchase as if for himself, and then convey the lot to the Baptists.”[9]

Mr. Russell was successful, and the ground for the First Baptist Church was broken during the summer of 1774.

John Angell married Mary Dexter, born in Providence on April 30, 1694. They were married on December 10, 1713, and according to records, had four children, Mary (1715), John Jr. (1720), James (1723), and Abigail (1729). He would survive his wife and all his children, dying on December 23, 1774, “in his 84th year,” the Providence Gazette reported in his obituary.” He was grandson of Thomas, “one of 12 founders of Providence,” the newspaper added.[10]

Even in death, Angell remains somewhat of an enigma. The Providence Gazette listed him as a member of the Society of Friends, but the Friends records record no John Angell among them in Smithfield or Providence. Moreover, Angell himself had told Ezra Stiles not to count him as a Quaker, but a follower of Gorton who “used the thee and thou language, but refused to be called Quaker or Friend.” The simple gravestone attributed as his resting place stands in the Old North Burial Ground, listing him as the son of James, but bearing the date of death as February 23, 1787, and the stone is a generation removed from his mother and brother’s amid the row of gravestones in the Angell plot in the North Burial Ground. This is the grave of John Angell Jr., born in 1720.

A wrong date writ on stone is not uncommon among eighteenth century stones, especially if it was erected sometime after the death, so it may be surmised that a name could be chiseled wrong as well, especially as it was some time after the father’s death. If John Angell could speak to us from the ages past he would tell us that there was no mystery. As a Gortonist, he would have eschewed memorials of any kind.

(Banner Image: The Clemence-Irons House, built in 1691, now owned by Historic New England (Robert A. Geake))

Footnotes:

[1] The best description the author has read on Gorton’s theology is Gura, Philip F., “The Radical Ideology of Samuel Gorton: New Light on the Relation between English and American Puritanism,” William & Mary Quarterly (Jan. 1979), pp. 78-100. [2] James, Sidney V., Colonial Rhode Island (Scribner, 1975), pp. 28-29. [3] Ibid. p.28. [4] Hamilton, Alexander, Gentleman’s ProgressThe Itinerarium of Dr. Alexander Hamilton 1744 Bridenbaugh, ed. (University of Pittsburg Press 1948), pp. 148-149. [5] Lancaster, Jane, Inquire Within (Oak Knoll Press, 2003), p. 12. [6] Bayles, Richard Mather, ed. History of Providence County (W. W. Preston & Co., 1891),p. 286. [7] Stiles, Ezra, The Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles,vol. 1 (C. Scribners Sons, 1901), pp. 185-186. [8] Letter from an editor of the Providence Journal entitled “The Hoyle Tavern,” in Arnold, James (ed.), Narragansett Historical Register, vol. 6 (1888), pp 313-314. [9] Kimball, Gertrude, Providence in Colonial Times (Houghton Mifflin, 1937), pp.360-361. [10] Providence Gazette notice recorded in Vital Records of Rhode Island, vol. 13 (Narragansett Historical Publishing Co, 1903), p. 121.