Fear not; no antagonism of interest would be the result of admitting in common to your workshops the colored mechanic, of admitting his child as an apprentice.

(Appeal to the Mechanics and Laboring Men of the State of Rhode Island, Providence Journal, October 27, 1869).

By the end of the Civil War, Republicans in the U.S. Congress placed the question of equality for African Americans at the forefront of a national political conversation as they sought to define the “new birth of freedom” President Abraham Lincoln had proclaimed in his Second Inaugural Address. Questions involving suffrage, land reform, labor reform, and social equality dominated political discourse.

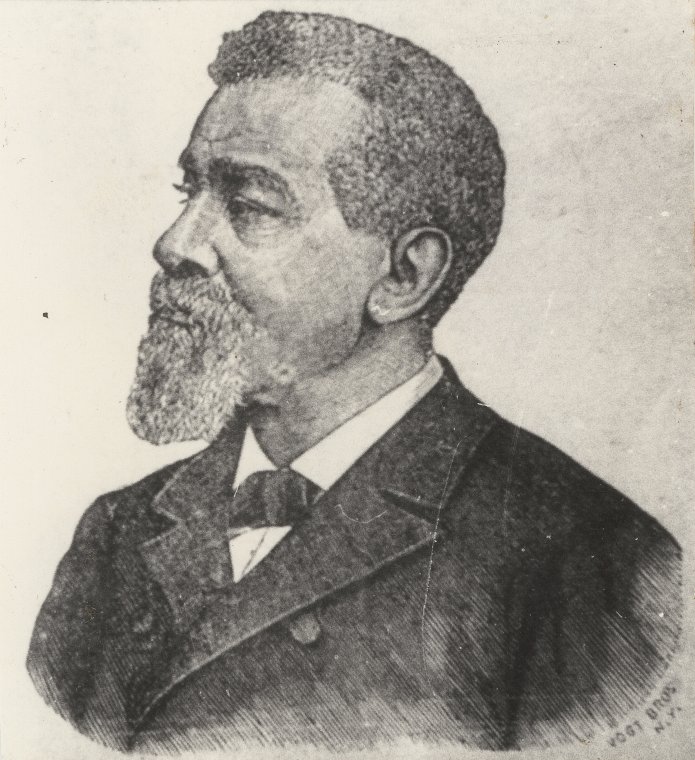

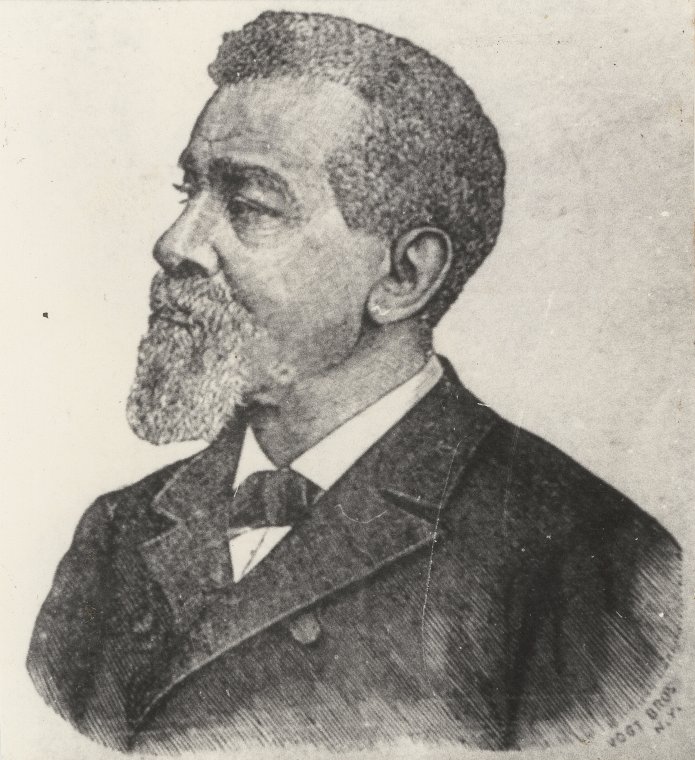

Black leaders in Rhode Island, such as the prominent Newport businessman and entrepreneur George T. Downing, helped to shape a conversation at numerous post-Civil War Black conventions. Downing’s business career followed in the path of his successful father Thomas Downing, a wealthy New York oysterman and restaurateur. In addition to the restaurant trade, Thomas Downing also was active in the antislavery movement, having known slavery first-hand as a youth. He was born into slavery in 1791 in Virginia. After he was manumitted, he moved to Philadelphia, and then to New York City by 1819.[1]

Along with his many siblings, George Downing grew up in New York City with a handful of future prominent abolitionists, including Alexander Crummell, James McCune Smith, and Henry Highland Garnet.[2] Downing and Garnet became rivals in the 1850s, when Downing rejected Garnet’s call for Black emigration out of the United States.

George T. Downing, businessman and civil rights leader (New York Public Library Digital Collections)

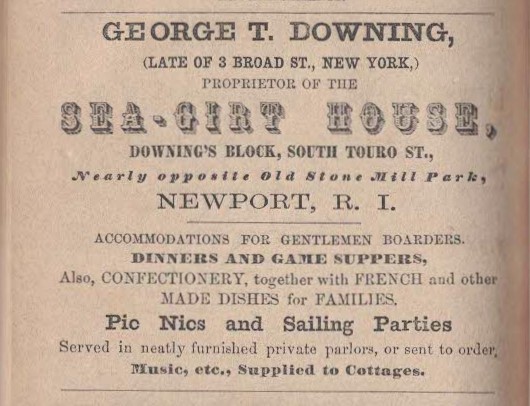

In the early 1840s, Downing met his future wife Serena Leanora de Grasse through the prominent upstate New York abolitionist Gerrit Smith.[3] Downing attended Hamilton College in Geneva, New York, and after having learned the restaurant trade from his father, moved to Newport, where he opened the Sea-Girt House in 1855.[4]

George T. Downing’s ad for the Sea Grit House, his hotel and restaurant business located on Newport’s Bellevue Avenue, near the Redwood Library and Athenaeum and the Newport Art Museum. The back street today is appropriately named Downing Street. From the 1856/1857 Newport Directory. (Russell Desimone Collection)

Downing spent considerable time advocating for integrated schools in Massachusetts in the 1850s, along with getting involved in some of the high-profile fugitive slave cases in Boston, including the rendition of Anthony Burns in 1854. Similar to his friend Frederick Douglass, Downing also corresponded with the abolitionist John Brown.[5]

In the 1860s, Downing, thanks to his close friendship with Massachusetts U.S. Senator Charles Sumner, managed the House of Representatives dining room, which gave him direct access to key members of the Republican Party. However, despite his economic success, Downing’s children were not able to attend public schools in Newport due to heightened levels of segregation. Downing’s activism, however, would open up only the state’s educational system.[6]

The itinerant Downing split his time between Boston, Providence, New York and Newport for much of his career. He attended numerous conventions in the pre-Civil War period focusing on civil rights for northern Blacks. These included a national convention in Troy in 1847, one in Rochester in 1853, one in Philadelphia in 1855, another in Boston in 1859 (where he served as its president), and the landmark Syracuse Convention in 1864 that led to the formation of the Equal Rights League, the precursor to the NAACP.[7]

Though the meetings sometimes are neglected by writers, the Colored Conventions Movement constitutes the 19th century’s longest campaign for African-American civil rights. Beginning in the 1830s, Black leaders organized state and national conventions across the country, calling for the end of slavery in the South, along with voting, legal, labor and educational rights in the North.[8]

Rhode Islanders Alfred Niger and George C. Willis were on the ground floor of this movement, attending the Convention of Free Persons of Color in Philadelphia in 1831.[9] A few years earlier Niger, along with George C. Willis, Ichabod Northup, and Peter Browning formed a Prince Hall (Black) Mason Lodge in Providence.[10] In 1836, Niger was instrumental in the creation of the Rhode Island Anti-Slavery Society.[11] Niger, a veteran of the first Black conventions in Philadelphia, went on to play a role during the Dorr Rebellion in an attempt to include African Americans in the elective franchise.[12]

During the Civil War, after Black soldiers were allowed to enlist into fighting regiments in the Union Army, Downing, along with his close friend Douglass, served as a military recruiter for the newly-formed Black units.[13] After the Union victory at Appomattox in April 1865, Downing continued to be an active participant in numerous Black conventions, including the Convention of the Colored People of New England held in Boston in December 1865 in which he “urged the importance to the colored people of having a representative in Washington to act for them, in the same manner as other classes are served there by their appointed agents.” Downing was selected by the convention’s nominating committee to be that Washington representative. He was in this sense a lobbyist for the rights of Black Americans.[14]

In January 1866, Downing, along with other prominent Black leaders, including Henry Garnet and Douglass, attended a convention in Washington, D.C. The delegates urged Congress to “guarantee and secure to all loyal citizens, irrespective of race or color, equal rights before the law, including the right of impartial suffrage,” which was “essential to secure liberty to the freedmen.”[15] The Convention appointed a delegation consisting of Downing, along with Frederick and Lewis Douglass to visit President Andrew Johnson to get his views on the program set forth in their resolutions.

Downing met Johnson in the White House in February 1866. Downing led off the meeting with a prepared statement, calling the Thirteenth Amendment, which ended chattel slavery, insufficient. The delegates demanded “their rights as citizens” and “equality before the law,” along with the right to vote. Johnson, a vehement racist, derided the Black delegation with his calls for colonization and denunciations of Black suffrage. Needless to say, Douglass and Downing departed in a dejected mood and did not go back to visit the president.[16] There would be no support from the White House during Johnson’s time in office.[17] Other than the end of slavery, Johnson did not view the Civil War as ushering in a radical change to race relations in American society.

Abolitionists, along with radical Republicans in Congress, saw things very differently and pushed for a new conception of federal authority to bring about a measure of racial egalitarianism. Building on their work in the antebellum period, Black activists continued to push for racial equality in public spaces, public accommodations, and voting rights.

Though the period of Reconstruction is often thought of as a southern issue, the North’s social structure also underwent a transformation in the 1860s and 1870s. In Rhode Island, African-American leaders used churches, newspapers and state conventions to press for the repeal of discriminatory laws, access to public facilities like schools, and better paying jobs.[18] Growing income inequality, the highest in American history until this point, prompted significant conversations. Throughout the country, nearly all unions barred Blacks from membership. The National Labor Congresses advocated the formation of segregated Black locals.[19]

The profound questions of civil and political equality on the table during the Reconstruction era occurred within the context of a large-scale economic revolution that introduced new questions relating to industrialized work. Labor rights, for example, were inextricably linked to the problem of emancipation and new definitions of freedom.[20] In the South, the labor question dealt largely with land ownership, in particular land titles for Black families who had, in many circumstances, worked parcels for generations. In the North, it was fears of “wage slavery” and dependency that rose to the forefront. The key was participation in the marketplace by free laborers. Black abolitionists linked labor reform with the quest for universal suffrage and a new constitutional amendment offering federal protection at the ballot box.

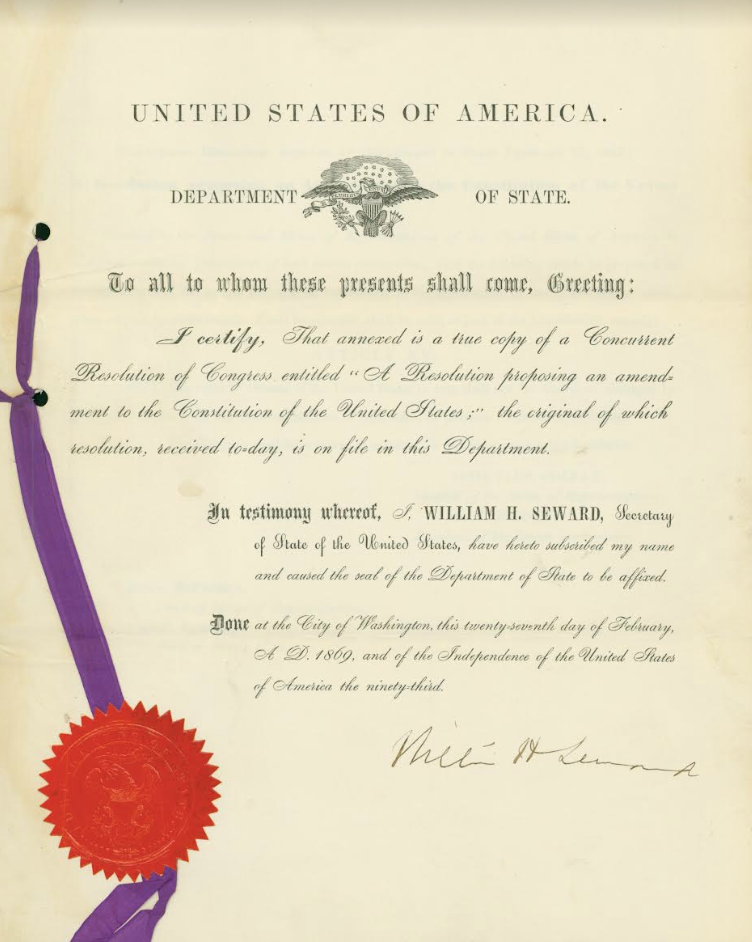

In 1868, the suffrage issue split the two major parties, with the Republicans, the party of Unionism and emancipation, standing behind governmental measures to expand the right to vote, while the Democrats, led by Horatio Seymour and Frank Blair, ran a campaign based on racism and violence. In November 1868, the majority of abolitionists viewed the Republican candidate Ulysses S. Grant’s victory over Horatio Seymour as a triumph for equal rights. A few months later, radicals within the ranks of the Republicans opened an intensive drive for a constitutional amendment to protect Black suffrage.[21]

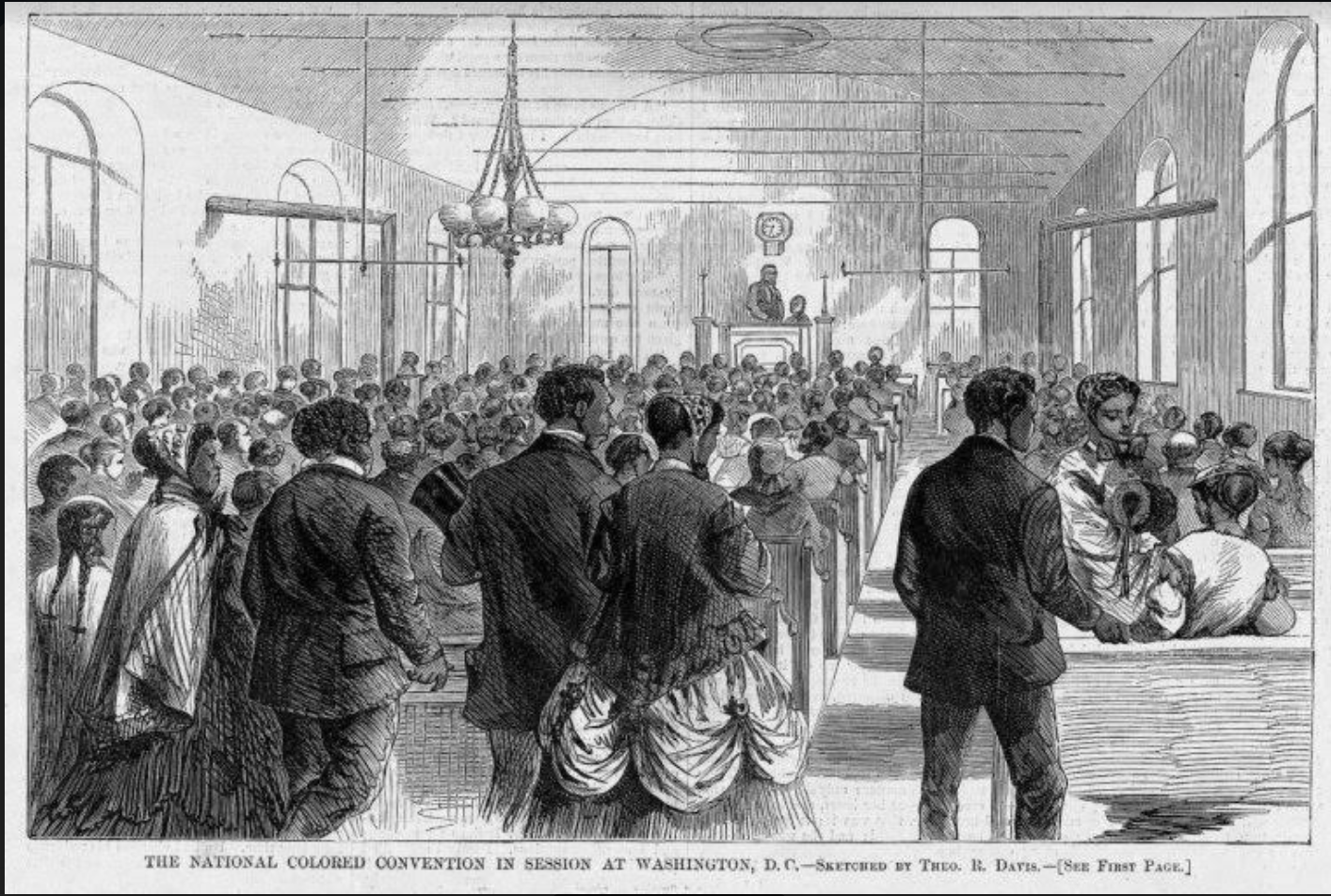

Speaking at the National Convention of the Colored Men of America in January 1869, Downing maintained that the Union victory meant that “the moral sense of the nation” had been “awakened” and now it was time to work beyond the battlefield in order to “secure some final measure of equal and universal suffrage, without any discrimination on the ground of race, color, previous condition or of religious belief.” Invoking language utilized by white and Black reformers during the Dorr Rebellion in Rhode Island several decades before, Downing maintained that the Constitution (Article IV, section 4) guaranteed to every state a “republican form of government.” According to Downing, this could only be achieved if suffrage was fully extended to all citizens and every citizen had a right to labor.[22] For Black Americans, the right to vote and the right to work were issues of economic and political life or death. Local union memberships and apprenticeship policies often barred African Americans as readily as they were denied access to the ballot box. Black reformers saw the Republican Party as the key to their full entrance into the body politic.[23]

“1869 National Colored Convention in Washington, DC,” by Theo R. Davis published in Harper’s Weekly, Feb. 6, 1869 (Russell DeSimone Collection)

Starting in 1869, the Rev. Mahlon Van Horne, pastor of the Union Colored Congregational Church on Division Street in Newport, hosted numerous gatherings in his church of civil rights leaders who worked tirelessly to combat the prevalence of racial discrimination. With the aid of Thomas Wentworth Higginson (a former colonel of a Black regiment in the Union Army) and Downing, Van Horne was elected to the Newport school board in 1872 and to the General Assembly in 1885. Van Horne’s church was often said to be “well filled” with Newport Black leaders.[24] “Our present may be considered as beginning with the completion of reconstruction and by the amended constitution which accords to the whole people every right belonging to man,” the “inspiration of hope is leveling the whole lump,” proclaimed Van Horne in a sermon in Union Congregational.[25]

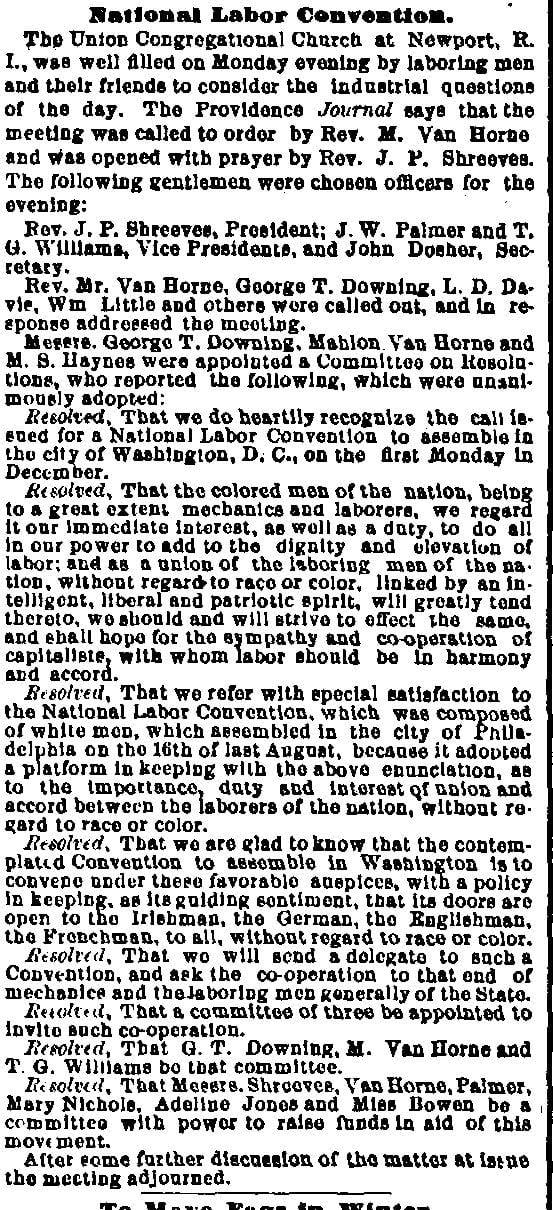

Downing was the “chief promoter of the movement” for a major state convention in Newport at the Colony House in late 1869.[26] Black leaders had been meeting in Rhode Island for months prior to the major national gathering, urging a “union of the laboring men of the nation, without regard to race or color.”[27] “It is an important move, and one of deep interest to every colored laborer in the land. The move looks to the elevation of labor, to a harmony and an accord between laboring men for the best interest, without regard to race or color.” Black leaders in Providence, including William J. Brown and George Henry, met at the Meeting Street Baptist Church in early October to discuss Downing’s plan for a state convention. And also for Rhode Island delegates to attend a planned national Colored Labor Convention later in the year in Washington, D.C.[28]

While white workers began to move towards socialist ideologies, African Americans held on to a vision of civic life “predicated upon collective self-government, property ownership, and full assimilation into the body politic.”[29] In late October 1869, Black leaders from the coastal communities of Bristol, Newport and Providence met at the Colony House, a meeting that has never been chronicled by historians.[30] The Rev. J.H. Burleigh of Providence served as president. Providence leaders readily agreed to make the trip to Newport to take part in the state convention and resoundingly endorsed the national colored labor convention planned for later in the year.[31]

Echoing Lincoln’s Second Inaugural, the delegates at Newport hoped that the nation would “atone” for the “long years of unrequited labor” and that the federal government would work towards the “future elevation” of Black Americans. The delegates made it clear that they stood behind the Republican Party and declared their intention not to throw their support to any third-party labor movements that could hinder the Republicans at the polls. They pledged their intention to create a committee to petition the General Assembly to remove any laws on the books that “proscribed men on account of their color.” They pleaded with shop owners to allow African American men and women into their employ on an equal basis with whites and with equal pay.[32]

Downing delivered an impassioned address, an “Appeal to the Mechanics and Laboring Men of the State of Rhode Island.”[33] John T. Waugh of Providence and Rev. Van Horne of Newport were selected to travel to Washington to represent Rhode Island at the upcoming national gathering of Black laborers.

The Newport Convention was noteworthy for two of its resolutions that had nothing to bear on the plight of the Black laborer who was locked out of white unions. The first was a resolution recognizing the “influx of Chinese” laborers to America. The Chinese were employed in the backbreaking work of building the transcontinental railway system and were entitled to the “protection and respect, which he shall justly merit.” The second resolution, offered by Downing, recognized “that working women, both white and colored are unjustly treated [and] not fairly compensated for their labor.”[34] This resolution came during a period when the Fifteenth Amendment was still pending formal ratification. The amendment granted the elective franchise to Black men, but not white or Black women. The fact that women were denied inclusion caused a split within the women’s suffrage movement and resulted in a disagreement between Frederick Douglass and Susan B. Anthony that would last for many years during which time they did not communicate.[35]

On December 6, 1869, over 200 Black delegates, including several female delegates, from virtually every state in the nation, crowded into Union League Hall in the nation’s capital to hear speeches on the condition of Black workers. Downing gave a stirring address to open the convention:

“We desire Union with the white laborer for a common interest; it is the interest of both parties, that such a union should exist, with a fair, open and unconcealed intent; with no aim to destroy any organization, political or otherwise; with no thought of fostering dishonor, whether in the nation or in the individuals; repudiating all attempts to weaken obligations engaged in openly, seriously, with a full knowledge of the same; with an intent to share honorably all obligations as nominated in the bond.”[36]

National Labor Convention article published in the October 17, 1869 edition of the Providence Journal (Russell DeSimone Collection)

As historian Philip Foner noted, for the first time in American history, Blacks “representing a wide variety of trades, occupations, and professions discussed the conditions of Negro labor in the United States and made recommendations on how to improve them.”[37] Downing was elected chairman of the Washington conference and later vice-president of the Colored National Labor Union. The Black workers union, unlike major white-only unions, welcomed a wide variety of trades, occupations and professions. The platform committee rejected the idea that the interests of big business was inimical to labor, signaling that no support would be given to third-party labor efforts that were growing in this period. The national officers, including Downing, were to serve as a Bureau of Labor and to promote state and federal legislation for the protection of the civil, political and economic rights of Black workers.

With the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment in March 1870, many abolitionists viewed their work as complete, but several prominent white abolitionists and their Black allies knew the mission was far from over. Wendell Phillips and Lydia Maria Child maintained that there was a “continued obligation resting upon Abolitionists” to never “cease their individual and collateral work, in all the various forms in which a man can influence his times, to blot out the idea of race in the minds of the American people.”[38] The “liberty of no man is secure who controls not his own political destiny. What is true of the individual applies to the community of individuals, or society at large. A people to be free must be their own rulers; each individual must in himself be an essential element of the sovereign power which composes the true basis of his liberty,” read an editorial in the New National Era.[39]

In 1871, at another Colored National Labor Union Convention, Downing offered a historical treatise on the plight of Black workers. The “colored laborer in America has been the special victim of avarice and cupidity from the time he first set foot on the continent,” proclaimed Downing. “He has been held in abject slavery, despoiled of all rights, consequently is, as must be the case, extremely poor. He was freed from the claim of an individual master and became more completely a slave to the impoverished circumstances that environed him.”[40]

In the years ahead, Downing, along with other Rhode Island Black leaders, continued to work towards federally enforceable civil rights. In 1874, in a challenge to the states’ rights argument that was used to justify discrimination, Downing maintained, “the very nice concern” whites “manifested for state rights, might receive more consideration” if it did not “oppose efforts on behalf of personal rights.” If an inn or restaurant, said Downing, “having its right to exist by virtue of state authority, being a creature of the state … shall make any discrimination between citizens of the United States on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude,” it may be said the state does the discriminating.[41]

The transmittal letter from the U.S. Department of State (signed by William H. Seward) annexing the text of the proposed Fifteenth Amendment (Rhode Island State Archives)

This is exactly what the U.S. Justice Department would argue, though not for nearly another century. The mid-20th century civil rights movement expanded upon the agenda laid out by Downing and other Black activists a century before as they sought to broaden federal protection for Black Americans in the areas of education, housing, voting and labor. The tactics and methods remained the same. The legacy of Downing’s career as a reformer, and his unwillingness to back down in the face of white extremism, can certainly be seen in the work of Martin Luther King, Jr. African Americans, noted Downing, had an “inseparable, providential identity” with America, and especially with its founding ideal of “universal brotherhood.” America existed in order to “work out in perfection the realization of a great principle, the fraternal unity of man.”[42]

ENDNOTES:

[1] See Thomas Downing’s obituary in The New York Times, April 12, 1866. [2] See the discussion of George Downing and other prominent 19th-century African-American reformers in this 1896 book authored by William Simmons, the president of a Black college in Kentucky: https://archive.org/details/menmarkeminentp00turngoog/page/n8/mode/2up?q=downing [3] See the entry on George Downing in the Encyclopedia of the African and the African-American Experience, edited by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. (Oxford University Press, 2005). For more on the de Grasse family, see Douglas Egerton, Thunder at the Gates: The Black Civil War Regiments that Redeemed America (Bloomsbury Press, 2017). [4] The Sea Girt hotel was located on Bellevue Ave not far from the Redwood Library and the Newport Art Museum. Today it is occupied by offices and a parking lot. The back street is appropriately named Downing Street. Downing’s personal papers can be found at Howard University in Washington, D.C. There is also a small collection at the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston. Despite his decades-long activism in the 19th century, little scholarly attention has been paid to Downing’s career. For a brief but informative overview of Downing’s life see Patrick T. Conley’s article for The Online Review of Rhode Island History at www.smallstatebighistory.com/george-t-downing-rhode-islands-most-prominent-african-american-leader/. See also Douglas Egerton, The Wars of Reconstruction (Bloomsbury Press, 2014) and Stephen Kantrowitz, More Than Freedom: Fighting for Black Citizenship in a White Republic, 1829-1889 (Penguin Press, 2012). [5] Kantrowitz, More Than Freedom, 248. [6] For more on the battle for integrated public education in Rhode Island in the 19th century see Erik Chaput and Russell DeSimone’s article for Small State Big History: http://smallstatebighistory.com/end-school-desegregation-rhode-island/ [7] Troy 1847: https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/279; Rochester 1853: https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/458; Philadelphia 1855: https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/281. Downing also attended several state-level conventions, including this one in Boston in 1854: https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/263 [8] The landmark Colored Convention Project is a must-see for students and scholars. The Colored Conventions Project (CCP) is a digital collection and hybrid site for research and teaching. For a discussion of Black Conventions in the pre-Civil War period, see Erik J. Chaput’s essay on Ohio at http://commonplace.online/article/teaching-antislavery-constitutionalism/. See also Kate Masur’s award-winning book, Until Justice Be Done (W. W. Norton, 2020). For the Civil War see Chaput’s discussion of the important 1864 Convention in Syracuse, NY at http://commonplace.online/article/right-path/ [9] The convention records can be accessed at https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/72 [10] The Harmony Masonic Lodge in Rhode Island was established at Providence in 1826 and evolved from the earlier Hiram Lodge of 1797. Members included the leading Black men of Rhode Island led by Alfred Niger and George Willis. Prince Hall had been in earlier correspondence with Providence and Newport African Societies and was aware of the progress in Rhode Island. The authors thank Keith Stokes for this information. [11] See C.J. Martin’s informative article, “The ‘Mustard Seed’: Providence’s Alfred Niger, Antebellum Black Voting Rights Activist,” in The Online Review of Rhode Island History @ www.smallstatebighistory.com/?s=alfred+niger. See also Martin’s important 2021 dissertation at https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/2199/. [12] See Erik J. Chaput, The People’s Martyr: Thomas Wilson Dorr and His 1842 Rhode Island Rebellion (University Press of Kansas, 2013), 55-57. See the records for the early national conventions in Philadelphia (1831, 1832, and 1833) on the Colored Convention Project website. [13] See Egerton, Wars of Reconstruction, p.396, note 39. [14] Access the file here: https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/590. [15] See Egerton, Wars of Reconstruction, 192-193; Washington National Republican, January 31, 1866. [16] See David Blight, Frederick Douglass’ Civil War: Keeping Faith in Jubilee (Louisiana State University Press, 1989), 190-191. [17] See Robert Levine, The Failed Promise: Reconstruction, Frederick Douglass, and the Impeachment of Andrew Johnson (W.W. Norton, 2021). [18] See Richard Archer, Jim Crow North (Oxford University Press, 2017) for an excellent account of racial discrimination in New England in the years leading up to the Civil War. [19] Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877, updated edition (New York, 2014), 479. See also Foner, Politics and Ideology in the Age of the Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980), ch. 6. [20] See Amy Dru Stanley, From Bondage to Contract: Wage Labor, Marriage, and the Market in the Age of Slave Emancipation (Cambridge University Press, 1998), ch. 1. [21] See James McPherson’s classic work, The Struggle for Equality (Princeton University Press, 1964), 417-430. [22] The text of this landmark convention (January 13-16, 1869) can be accessed here https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/452 For issues of race and republicanism during the Dorr Rebellion, see Erik J. Chaput and Russell J. DeSimone, “Strange Bedfellows: The Politics of Race in Antebellum Rhode Island,” Common Place (2008) at http://commonplace.online/article/strange-bedfellows/ [23] For more on Reconstruction and Black Suffrage see Erik J. Chaput’s piece for the New York Times’ Disunion series at https://archive.nytimes.com/opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/02/01/the-reconstruction-wars-begin/ [24] The Sun (Baltimore), October 2, 1869. [25] An 1887 Van Horne sermon quoted in Keith Stokes, “Our Hidden History: Newport Pastor Was a Champion of Social Justice,” Providence Journal (January 16, 2021). See also Stokes, “A Matter of Truth: The Struggle for African Heritage and Indigenous People Equal Rights in Providence, Rhode Island, 1620-2020 ( Rhode Island Black Heritage Society & 1696 Heritage Group), 55-61. Accessed online at https://upriseri.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Matter-of-Truth2.pdf [26] Providence Journal, October 25, 1869. [27] The Sun (Baltimore), October 2, 1869. [28] Evening Bulletin, October 14, 1869. [29] Benjamin Lynerd, “Republican Ideology and the Black Labor Movement, 1869-1872,” Phylon (2018), 20. [30] This convention does not appear on the Colored Convention Project webpage. It came at a time when many other interest groups were also holding conventions in Rhode Island. The week before, the Rhode Island Labor Union held a two-day convention in Providence attended by noted abolitionists S.S. Forster and Arnold B. Chase, as well as woman suffragist Paulina Wright Davis. On October 21, also in Providence, the Rhode Island Woman Suffrage Association held their convention. [31] Evening Bulletin, October 14, 1869. For more on Henry, see his 1894 autobiography, which can be accessed at https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/henryg/henryg.html; Brown published his autobiography in 1883. Historian Joanne Pope Melish’s 2006 edited version of Brown’s work is a must-read for students of 19th century Rhode Island history. See The Life of William J. Brown of Providence, R.I. (New Hampshire, 2006). [32] Providence Journal, October 27, 1869. [33] Providence Evening Press, October 26, 1869. [34] Ibid. [35] See historian Leigh Fought’s account of the women in the life of Frederick Douglass for more in Women in the World of Frederick Douglass (Oxford University Press, 2017). [36] The 1869 Convention records can be accessed at https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/591 [37] Philip S. Foner, Organized Labor and the Black Worker, 1619-1981, rev. ed. (Haymarket Square Books, 2017), 35-36. [38] Quoted in McPherson, The Struggle for Equality, 427-428. [39] New National Era, March 10, 1870. It was the official organ of the Colored National Labor Union. Frederick Douglass served as the editor. Downing played an instrumental role in helping to garner financial support for the paper in its early stages. See also See Philip Foner, ed., The Selected Speeches and Writings of Frederick Douglass, abridged and adopted by Yuval Taylor (Lawrence Hill Books, 1999), 602-603. [40] Quoted in Foner, Organized Labor and the Black Worker, 40-41. [41] Quoted in James M. McPherson, “Abolitionists and the Civil Rights Act of 1875,” The Journal of American History 52:3 (1965), 505. [42] Downing’s presidential address to the New England Colored Citizens Convention can be found in the Liberator, August 19, 1859.berator, August 19, 1859.