On November 6, 1860, Abraham Lincoln became the victor in a tight, four-way race for president. The country was bitterly at odds—more divided than an any point of its history. Southern extremists, believing that slavery was under attack, threatened to destroy the Union by seceding.

The period after the election of Abraham Lincoln as president of the United States in November 1860 and his taking office on March 4, 1861 was one of the most turbulent and unsettled in the country’s history. Would southern states secede? If so, how many? Would the North insist on war to bring the seceded states back into the Union? The stakes were incredibly high.

One of the great questions in U.S. history is why did the North insist on going to war with the South? Why didn’t the North let the South go its own way and avoid the horrible bloodshed of a Civil War? The letters from Rhode Islanders quoted in this article help to explain why.

Photograph of Abraham Lincoln taken on June 3, 1860, after his nomination but before his election, by Alexander Healey at Springfield, Illinois (Library of Congress)

The election of 1860 was a watershed for the southern states and their institution of slavery. Lincoln was clear that if elected president, he would not interfere with slavery in states where it then existed. He recognized he would have no authority under the U.S. Constitution to do so, without amending the U.S. Constitution. However, Lincoln was firm that he opposed the expansion of slavery into western territories. Lincoln thought that the federal government did possess the power to prevent such expansion.

Most of the South virulently disagreed. Even though Lincoln pledged that he would not interfere with slavery where it already existed, this was not enough for the fire-eaters in the South. Even the day before the election, a U.S. Senator from South Carolina harangued a crowd in Columbia, South Carolina, “A line of enemies is closing around us which must be broken . . . . I would ring the clarion note of defiance in the insolent ears of our foe. . . . It is your duty . . . to withdraw,” that is, secede from the Union.

Meanwhile, the country continued to be led by the weak president, James Buchanan, a Democrat from Pennsylvania. Buchanan had relied on the southern states for his election and had many southerners in his cabinet. While Buchanan did not want the southern states to secede, he did not want the federal government that he led to exercise force against them either.

South Carolina seceded from the Union on December 20, 1860. Whether other southern states would follow was an open question. But they did, starting with Mississippi (January 9), Florida (January 10), Alabama (January 11), Georgia (January 19), Louisiana (January 26), and Texas (February 1). Four more states seceded after April, making a total of eleven states.

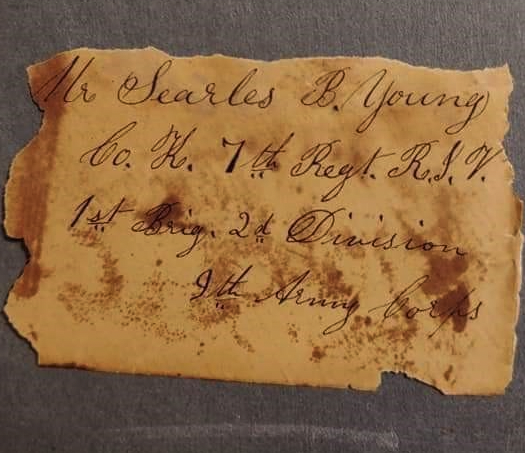

The viewpoints of Rhode Islanders from the period from November 14, 1860, to February 2, 1861, are reflected in letters sent to James F. Simmons, one of Rhode Island’s two U.S. Senators. Simmons, from Little Compton, was a member of the Republican Party and was generally conservative in his politics—more conservative than Lincoln.

At the time, there was great pressure among Republicans to compromise with the Southerners, including Republican leaders such as the influential New York newspaper editor Horace Greeley and even from Lincoln’s former rival, U.S. Senator William Seward. Those who favored compromising with the South in order to avoid secession or war are reflected in a few of the letters quoted below.

But the strongest feelings in the letters mailed to Senator Simmons came from fellow-Republicans who demanded that the Rhode Island delegation in Congress not yield to the South, even if it meant war. There is an undercurrent that the Republicans at home in Rhode Island were worried that its two U.S. senators in Washington, D.C. might compromise with the South and they would have none of it. Senator Simmons must have raised eyebrows when, in a speech in the U.S. Senate, he boasted that he had lived under every president of the United States and that the prospect of civil war threatened a bloody close to not only to the Union but to a glorious era of United States history.

This is the first time quotes from these letters have appeared in a publication. None of the relevant letters in the files of James F. Simmons held by the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. are from Simmons—they are all to him.

The first letter written to Senator Simmons was from Rowland R. Hazard, Jr. of Newport. He was an arch conservative. He had been a delegate from Rhode Island at the Republican Party convention held in Chicago in May 1860. As I wrote in a prior article, the Rhode Island delegation, shockingly, did not cast a single vote for Lincoln in the first round of voting at the convention. Instead, they cast five of the state’s eight votes for Judge John McLean of Ohio. McLean had no chance of winning but was viewed as more conservative than Lincoln. These votes show that Hazard and other delegates must have thought Lincoln was too progressive for their conservative beliefs. However, they recognized that Lincoln was more moderate than the favorite to win the race, William H. Seward of New York. With many delegates believing that it would take a moderate to win the general election, Lincoln, remarkably, won the Republican Party’s nomination. Rhode Island’s delegates did cast votes for Lincoln in the second and third (and final) rounds at Chicago.

Most of Hazard’s November 14 letter, written shortly after the election of Lincoln on Tuesday, November 6, and before South Carolina seceded, was about appointing Republican conservative friends of the Republican Party to federal offices. But he added at the end of his letter, “Hoping that the good work we so well commenced at Chicago may result in finally restoring our country to its old harmony and a new and higher glory.” This reference was an indication that Hazard wanted Lincoln to return to the status quo by appeasing the South and avoiding secession at all costs.

Rhode Island election ticket for the Republican Party with Abraham Lincoln at the head of the ticket. Ballou and Buffum wrote letters to Senator Simmons that are quoted in this article (Russell J. DeSimone Collection)

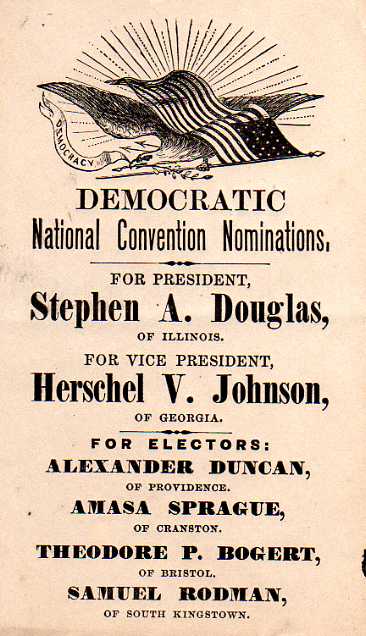

The next two letters came from Republican Party leaders, L. W. Ballou from Cumberland and Edward Harris from Woonsocket. They had helped to engineer Lincoln’s speaking at Woonsocket earlier in the year on March 8, 1860. Ballou appeared as a state elector on the ticket for the Republican Party, with Lincoln at its head. Neither of them was in a mood for compromise with the South.

Ballou sent Simmons a strong letter, dated December 18, 1860. By this time, it was known that South Carolina was serious about threatening to secede from the Union. Ballou wanted Simmons to remain steadfast against southern threats of secession:

Our people in this section of the State are calm but firm. They want no compromises. They will take “no step backwards.” They are for Freedom and the Constitution as it is. If we have done anything wrong, we will undo it because it is wrong and not because of anybody’s [i.e., the South’s] threats.

A common theme in the letters to Simmons is that the controversy over slavery with the South had gone on long enough—for decades—and needed to be resolved, once and for all:

We . . . cannot compromise basic principles for which we have contended; and if we could, it would but prolong the contest, for nothing is settled till it is settled right. And certainly the present [circumstances] of the people of the South does not convince us that the extension of their “peculiar institution” would be the perfect blessing, or that is the highest point of prosperity and glory to which human governments may attain.

Ballou must have believed that Senator Simmons was at risk of backsliding in dealing with the South. His conclusion contained not-too-subtle warnings:

The times require all the Patriotism, Wisdom, and Prudence of our Statesmen, and above all that firmness which will neither be intimidated by threats nor faintest by promises, but will “be just and fear not.”

Our delegation in Congress will be sustained at home in defending the Constitution as interpreted by the Republican Party.

Edward Harris wrote to Simmons a letter, dated January 3, 1860, along the same lines as Ballou’s letter. By this time, South Carolina had voted to seceded from the Union. Harris noticed a shift among Republican conservatives in the state against compromising with the South. Harris wrote:

You would think I was raised Ultra almost an Abolitionist. But I tell you Senator Simmons, our conservative friends . . . are now far in advance of me. I now hear of but one expression from our Republican friends—that is “I hope our Republicans will stand up to our principles. We want no more compromises with slavery. We want this thing settled and settled for all time, and settled in the right way for Freedom.

Rhode Island election ticket for the Democratic Party with Stephen A. Douglas at the head of the ticket. Lincoln easily beat Douglas in the November election in Rhode Island (Russell J. DeSimone Collection)

Those who supported the Union became concerned when South Carolina secessionists began threatening to attack and take over the federal fort at the entrance to Charleston Harbor, Fort Sumter. The fort’s garrison was commanded by Major Robert Anderson. Harris wrote about the topic. He saw a “firmness of Principle, which takes with the people. Now Major Anderson is applauded. He is a very popular man.”

Harris then warned of what would happen if Republican Party members in Congress compromised with the South:

I beg of you to strengthen the weak . . . and don’t let them [weaken] Republican principles. The Masses will sustain the party if they [Republican Party members of Congress] are true to principle. If they fall in we are broken. This is what our so-called Democratic leaders want. They want to debauch the Republican Party by [our] caving in; they . . . know the masses of the People will sustain the Republicans if they [the Republican Party members of Congress] stand up to principle. But if they [the Republican Party members of Congress] can get there by compromise, they [Democrat leaders] will tell us, “We told you so.” “We told you the Republican leaders meant nothing but to get into power.” . . . . Don’t let them debauch our [Republican] Party I beg you.

The next letter, from Isaac Saunders of North Scituate, was even stronger in insisting that the Republicans in Congress not compromise, even if it meant war with the South. This letter is dated January 18, 1860, by which time three other southern states had joined South Carolina in seceding from the Union:

I suppose you are having exciting times at Washington, but be sure that you make no concession for peace that will involve any questions that you have sacrificed principle for the sake of Peace. I want to see the bone taken out of the sore of secession. If it shall require us to go through a Civil War and so far as the mass of our citizens of R.I. is concerned, it is their feeling on the question, the feeling so far as I know, is to give the South every right that belongs to them, and that we will have ours and ask for nothing more.

Saunders, interestingly, was willing to let South Carolina secede, without going to war to bring the state back into the Union: “Now I look upon South Carolina as a part of our federal government . . . Now I think it would be for the interest and quiet of the northern States to let South Carolina go out and Stay Out.”

Still, Saunders expressed concern that Rhode Island’s other U.S. Senator, Republican Henry B. Anthony, was too willing to compromise with the South. He also included a veiled threat to Simmons if he backtracked. Saunders wrote Senator Simmons:

I do not know and hope it is not so, but rumor says our colleague is a little shaky and inclined to fear we shall have trouble if we do not quiet the South, by concession which would be questionable in their character. But I trust for his honor and standing and yours also that you will adopt[the] motto, be sure you are right and the go ahead, and your constituency will back you up by their votes and their arms and muscles if need be.

Saunders ended his letter making it clear he was not afraid to go to war, if it came to that:

Major Anderson is the Hero of the day with us. I have no doubt that this state if called upon to enforce the laws would furnish in ten days 5,000 soldiers. You may depend that the Public Sentiment is that the federal laws shall be enforced in accordance with the Constitution.

Saunders then criticized President James Buchanan with being weak on secession. He ended his letter emphasizing that he too wanted the controversy with the South settled once and for all time:

[W]e have had trouble enough already about secession and as we are it, we had better have a final settlement now. Let us find out whether we are a government or not, and if there is not cohesiveness to hold together under the Constitution I prefer to know it, and do not wish to have it postponed for my children.

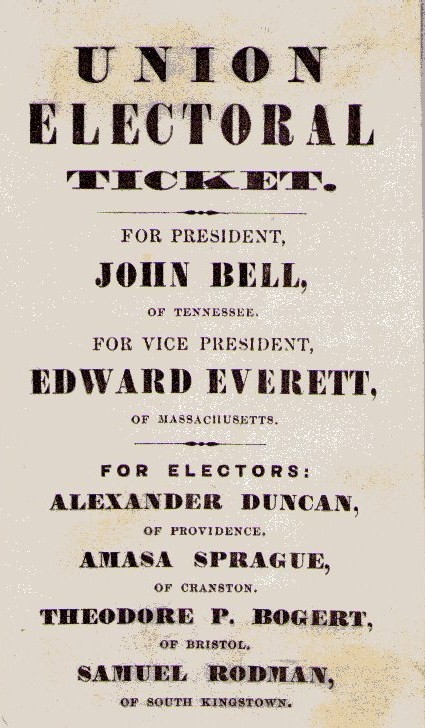

Rhode Island election ticket for the Union Electoral Ticket headed by John Bell of Tennessee. Bell did not support stopping the extension of slavery in western territories and he did not support southern succession. Interestingly, the electors for this ticket were the same for the Democratic ticket—there was a fusion between the two parties. Bell performed fairly well in border states such as Maryland, but he made little impression in Rhode Island in the November election (Russell J. DeSimone Collection)

The next letter came from eighty-year-old William Peckham of Wakefield. He was born before the end of the American Revolutionary War, cast his first vote for president for Thomas Jefferson, and served in the Rhode Island militia opposing Thomas Dorr’s forces during the Dorr War in Rhode Island in 1842. Peckham explained that:

I have no less than five sons and five daughters with their offspring settled in these states of the Union. You will readily perceive that I have a deep stake in the perpetuation of the Union. And if necessary I would shoulder my gun and with others would march to the City of Washington to protect the inauguration of the President [Abraham Lincoln of Illinois] and vice-president elect [Hannibal Hamlin of Maine].

Peckham was angry that President Buchanan refused to garrison the federal forts along the east coast in the South and to properly support Major Anderson at Fort Sumter. He also alluded to the threats of violence, and actual acts of violence, perpetrated by members of Congress from the South. (In 1858, Congressman Pierce Butler from South Carolina had infamously caned U.S. Senator Charles Sumner from Massachusetts while Sumner was stuck at his desk in the Senate, causing serious head injuries to the abolitionist senator). Peckham wrote, “the South has been so long indulged in their knock down arguments, of which Senator Sumner has had full proof, that they are determined to bully the North and West at pleasure . . . .”

Peckham ended his letter to Simmons with the familiar theme of standing firm against the South: “My prayer to God is that the free states men will not again turn pale like the former Doughfaces and thereby encourage more bullying from the southern fire-eaters.” (Doughfaces were northerners who favored the southern position in political disputes.)

Bill Larned of Providence, in a January 19, 1861 letter, addressed a demand by some extremist Congressmen from the South that the U.S. Constitution be amended to allow slavery in all the western territories. He wrote, “The idea of expecting us in this age of Christianity to go back and place ourselves in a position that the South would not dared to have asked of us twenty years ago is to my mind, and most of those I talk with, absolutely insulting.” Larned then had a warning that a new political party could be created in the North if northern Republican Party congressmen compromised too much with the South:

I feel quite sure it will never come to this, but if those who represent us in Washington consent to any such arrangement, you may be sure it will start a party [in the] North that will make trouble, because they will feel they have been betrayed and it seems to me the time has gone by to expect us to yield everything the South may demand.

Larned ended his letter with a familiar refrain:

We think it’s time to find out if we have any Government, and if so whether it is free or slave. Thus far we have been ruled by the slave power, but hereafter we hope for better things, and to effect this we must be firm and not be frightened by threats of the rebels who have managed this miserable attempt to overthrow the Government which will soon exhaust itself if we show the proper spirit.

Simmons received a single letter from Middletown and Newport arguing that peace should prevail at all costs. It was from David Buffum, who also appeared as a state elector on the ticket for the Republican Party, with Lincoln at its head. Buffum wrote:

Will it not be the better course if the seceding states cannot be prevailed upon to return upon satisfactory terms to let them off as quietly as possible and retain their goodwill as much as may be, and in process of time they might and very likely could manifest a desire to be restored to the brotherhood of states, who have been so signally blessed and prospered together that I believe the history of the world shows nothing equal to it.

. . . .

Peace is hardly ever, in my view, preserved at too great a sacrifice, and War never or rarely ever, I believe gains the full object for which it is undertaken, and if there must be a full and final separation between the free and slave states it has occurred to me that the free states can do so much better without the Slave States, than the Slave States can without the free, and trade and commerce may be carried on between the two sections as heretofore.

It may be that Buffum was a member of the Quaker sect. In any case, even he seemed to be frustrated by the demands of the South:

I am acquainted with many Antislavery men and I have no recollection of ever hearing one of the men express an opinion in favor of interfering with slavery in the States where it is established by the law of the land. They admit that they have no legal right, however much they may regret its existence. I have for many years had a fear that the United States extending over such a vast territory and such diversified interests would not ultimately break to pieces, like a very long ship upon a rock or sand bank break to pieces of its own weight.

Buffum’s view advocating peace and allowing the seceded states to go their own way was, however, the minority one in Rhode Island.

What would have happened if Buffum’s suggested approach of allowing the South to secede had been adopted? Southern leaders were already talking about annexing Cuba and parts of Central American and making them slave territories. There likely would have been frequent wars between the North and South over western territories. When would slavery had ended in the South? It would have occurred well after 1865, the end of the Civil War. The end of slavery in the South, in any event, likely would have resulted in an apartheid regime even harsher than the horrible Jim Crow regime that dominated the South in post-war years up to the early 1960s. During the World War II years, would the South have become an ally of Nazi Germany, given their common views on white racial superiority? If that had occurred, it would have forced the United States to deal with the South before it could address the existential threat posed by Nazi Germany, never mind containing the threat of the expanding imperialist and warmongering Japanese empire. This is all speculation, but readers, you get the drift. It would not have been good for the North and the cause of freedom to have allowed the South to go its own way in 1860.

After Lincoln was inaugurated as president on March 4, 1861, Lincoln stood firm on two of his key decisions: to oppose the expansion of slavery in the western territories and to oppose the rebellious South. He showed firmness in defending the federal government’s rights at Fort Sumter. He sent a naval force intended to resupply Major Anderson at Fort Sumter. But on April 12, southern artillery surrounding Charleston Harbor bombarded and pummeled the fort, forcing Anderson and his small garrison to surrender two days later. The Civil War had begun. More than 600,000 Americans would die in the war, the most by far of any war in the country’s history.

I was fortunate to be one of the visitors who handled the U.S. flag at Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor on the first day that National Park rangers did flag raisings, May 30, 2021, since the start of the pandemic in March 2020. Here the flag I helped raise flies over the fort. After Major Robert Anderson surrendered the fort to Confederate forces on April 12, 1861, it was subjected to a 22-month siege by Union naval forces and reduced to mostly rubble during the Civil War in 1864 and 1865 (Christian McBurney)

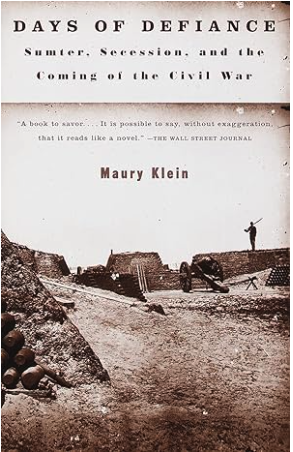

To read more on this topic, I highly recommend Maury Klein’s Days of Defiance: Sumter, Secession, and the Coming of the Civil War (Vintage Books, 1997). Klein, an outstanding history author, is now a retired history professor from the University of Rhode Island. This outstanding book is sold in the gift shop at Fort Sumter (I bought one at the gift shop with a stamp from Fort Sumter affixed on the first inside page). The book explains how America took those last, fatal steps to war. I found remarkable the threats of war and other extremism from the secessionists from South Carolina.

The quote from the U.S. Senator from South Carolina and the quote from Senator Simmons about the consequence of civil war is from Days of Defiance, pages 92 and 218.

I credit Ed Achorn with alerting me to the existence of the correspondence of James F. Simmons held by the Library of Congress. Formerly the long-time chief editor of the editorial page for the Providence Journal, Ed is the author of two excellent Lincoln books: The Lincoln Miracle, Inside the Republican Convention that Changed History (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2023) and Every Drop of Blood: The Momentous Second Inauguration of Abraham Lincoln (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2020).

For a related article published in the Online Review of Rhode Island History, see Christian McBurney, “Rhode Island Fails to Vote for Lincoln for President at Nominating Convention!,” at https://smallstatebighistory.com/rhode-island-fails-to-vote-for-lincoln-for-president-at-nominating-convention/.