It is odd but true that the little state of Rhode Island produced two heroes in the giant state of Texas during Texas’s formative years. One hero was Albert Martin of Providence, who performed brave deeds at the Alamo in 1836. The other was Little Compton’s Abel H. Pierce, better known as Shanghai Pierce, who became one of the legendary cattle barons of Texas in the late nineteenth century.

Albert Martin of the Alamo, by Brian Wallin

One of the most famous documents in American history, “To the People of Texas and All Americans in the World,” was written by Lt. Col. William B. Travis as a plea for reinforcements to defend the Alamo against Mexican forces during the Texas Revolution in 1836. Intimately connected with this letter is Albert Martin of Providence.

Albert Martin was born in Providence on January 6, 1808 to Joseph S. Martin, a merchant, and Abby B. Martin. They were fourth cousins and both of their fathers had fought on the patriot side in the American Revolution.

Albert left Rhode Island at the age of eighteen to attend Norwich University in Vermont. He never returned. By the time he completed his college education, his family had relocated. Martin joined his father and brothers in the mercantile business, first in Tennessee and then in New Orleans. In 1835, he moved to Gonzales, Texas, taking advantage of land grant offers and opening there a general store (a branch of his family’s mercantile business), called Martin, Coffin & Company.

The Texas Revolution broke out in 1835. Albert was involved in the defense of Gonzales (about seventy miles from the Alamo) and Bexar (the original name of San Antonio) where he was wounded.

On February 23, 1836, a Mexican army numbering some 1,500 soldiers under General Santa Anna laid siege to Texans (then called Texians) holding the Alamo. Martin, now a Captain in the Texas Rangers, returned from Gonzales and was immediately sent by Colonel Travis to meet an aide of General Santa Anna’s, but the Mexican refused to see him. The following day, Colonel Travis entrusted Martin to deliver an open letter to San Felipe de Austin containing a plea for reinforcements. Texans today revere this stirring language as their version of the Declaration of Independence:

TO THE PEOPLE OF TEXAS & ALL AMERICANS IN THE WORLD:

Fellow citizens and compatriots: I am besieged by a thousand or more of the Mexicans under Santa Anna. I have sustained a continual Bombardment and cannonade for 24 hours & have not lost a man. The enemy has demanded surrender at discretion, otherwise the garrison are to be put to the sword, if the fort is taken. I have answered the demand with a cannon shot, & our flag still waves proudly from the walls. I shall never surrender or retreat. Then, I call on you in the name of Liberty, of patriotism & everything dear to the American character, to come to our aid, with all dispatch. The enemy is receiving reinforcements daily & will no doubt increase to three or four thousand in four or five days. If this call is neglected, I am determined to sustain myself as long as possible & die like a soldier who never forgets what is due to his own honor & that of his country – Victory or Death.

William Barret Travis

Lt. Col. comdt

P.S. The Lord is on our side. When the enemy appeared in sight we had not three bushels of corn. We have since found in deserted houses 80 or 90 bushels and got into the walls 20 or 30 head of Beeves.

This 1833 Springfield Rifle would have been the type used by many of the Texans at the Alamo (Varnum Armory Museum Collection)

With Travis’s letter safely packed away, Martin rode through the night back to Gonzales and handed the letter to a colleague, Lancelot Smithers. On the way, Martin added two personal postscripts. First, he wrote of his fear that the Mexican army had already launched an attack on the fort and added urgently, “Hurry on all the men you can in haste.” The second is hard to read since the letter has frayed along a fold. But, it appears to convey that the Texans were “determined to do or die.” Smithers penned his own postscript to the letter and carried it on to Austin. The letter was widely published, but it took some time for a large force to be assembled.

Back in Gonzales, a small relief force of thirty-two men set out for the Alamo. Against his father’s wishes, Martin went with them and on March 1 made it back into the fortress. Five days later Albert was among the 188 men killed in the Battle of the Alamo. In April of 1836, an American army under General Sam Houston defeated Santa Anna at the Battle of San Jacinto.

Martin’s body was never recovered. It was likely among those burned by the Mexicans who then scattered the ashes of the Alamo’s defenders. The original Travis letter survived and is now in the Texas State Library in Austin, where a copy is on public display.

In July of 1836, Martin’s obituary was published in the New Orleans True American newspaper. It reads, in part: “Among those who fell in the storming of the Alamo was Albert Martin, a native of Providence, Rhode Island and recently a citizen of this city. . . . He had left the fortress and returned to his residence. In reply to the passionate entreaties of his father, who besought him not to rush into certain destruction, he said ‘this is no time for such considerations. I have passed my word to Colonel Travers, that I would return, nor can I forfeit a pledge thus given.’ Thus died Albert Martin, a not unapt illustration of New England heroism. He has left a family, and perhaps a Nation to lament his loss and he had bequeathed to that family an example of heroic and high-minded chivalry which can never be forgotten.”

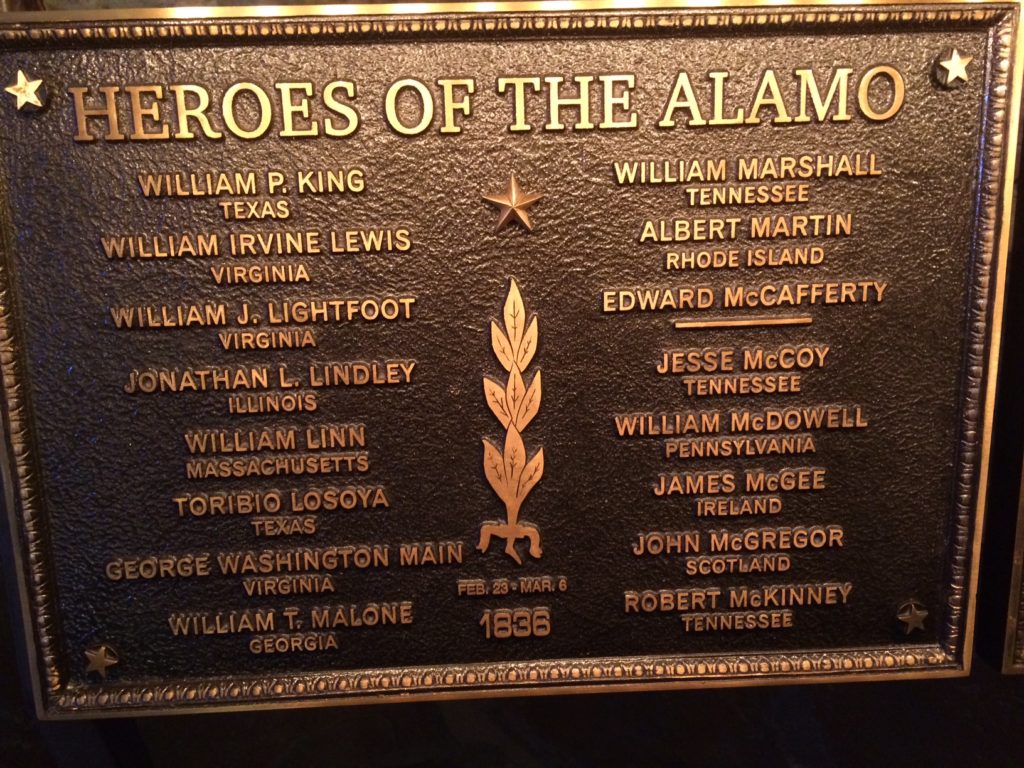

There is a cenotaph at the Martin family plot in Providence’s North Burial Ground memorializing Albert.Although a pamphlet distributed at the Alamo correctly states Martin was a Rhode Island native, a plaque at the memorial for many years said he hailed from Tennessee. After complaints by Rhode Islanders, this mistake was recently corrected, as indicated in the photograph of it in this article, taken in March 2018. Martin can now really rest in peace.

At the Alamo, a series of plaques names each man killed during the siege and where the man came from. Albert Martin, second one down in the right-hand column, is finally properly identified as hailing from Rhode Island (Christian McBurney)

For further reading:

Daughters of the American Revolution, The Alamo Heroes and Their Revolutionary Ancestors (San Antonio, 1976).

Michael R. Green, “To the People of Texas and All the Americans in the World,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly 91 (April 1988).

Bill Groneman, “MARTIN, ALBERT,” in Handbook of Texas Online (http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fma57), accessed September 22, 2015. Uploaded on June 15, 2010. Published by the Texas State Historical Association.

www.geni.com/people (Albert Martin)

texasheritagesociety.org/The-Travis-Letter-Victory-or-Death-.html

www.wikitree.com (Albert Martin)

http://en.wikipedia.org “Albert Martin (soldier)”

Shanghai Pierce, Cattle Baron, by Christian McBurney

Abel Head Pierce was born June 29, 1834, in Little Compton, Rhode Island, one of ten children of Jonathan D. and Hannah (Head) Pierce. While Abel was a direct descendant of John Alden and Priscilla Mullins of Mayflower fame, his family managed to live a humble existence from their Little Compton farm and his father’s job as village blacksmith. Abel received a modest education in 1848 and 1849 at a one-room school house at Little Compton. He gained the nickname of “Shanghai,” not because of any connection to China, but because he grew to be so tall his too-short trousers made him, according to his friends, resemble a Shanghai Rooster. Shanghai grew to be a towering 6 feet 4 inches tall.

The young, rambunctious and ambitious Shanghai, who tested wills with his father and realized it would be difficult to become rich in Little Compton, moved to Petersburg, Virginia, where he apprenticed as a clerk in a general store owned by his mother’s brother. He outgrew this job too and at the age of nineteen he stowed away on a schooner that landed in Texas in October of 1853. Like Albert Martin, he never returned to Rhode Island.

On the south Texas coast, Shanghai learned how to become a cattleman the hard way. He began work splitting rails for fences for $15 a month. He bristled at the fact that his employer, W. B. Grimes, then one of the premier Texas cattlemen, had him break in wild horses in lieu of one of Grimes’s slaves, for if the slave was killed, it would cost his master $1,000, while if Shanghai was killed, it would cost Grimes nothing. Once Pierce asked Grimes to pay him in cattle. His employer gave him stock well beyond their prime, many of which died the next year. When the Civil War broke out, the Yankee-born Pierce enlisted in the 1st Texas Cavalry, where he gained experience as a cattle driver and butcher, serving beef to the soldiers of the regiment. (Shanghai, a great storyteller, claimed that he held the rank of a major general, because when his regiment advanced, he brought up the rear, and when the regiment retreated, he was always in the lead.) When the war ended he returned to Grimes’s ranch to collect money owed to him, but Grimes paid him in worthless Confederate money. Grimes boasted that he was simply “teaching a Yankee the cow business.” It may have been the case that W. B. Grimes was sending a message that he did not want Pierce courting his daughter. In any event, the embittered Shanghai would not forget the incident.

After the war, Shanghai and his brother from Little Compton, Jonathan, partnered with substantial cattlemen and began a successful business shipping cattle from the south Texas coast to markets in New Orleans. He also married and had two children (his first wife died young and he later remarried). Shanghai began to build his own herd of cattle in Matagorda County, taking many strays running wild on the free range, which was then not illegal. At the time, the price of hides was high and he immediately had many of them butchered. Shanghai started to increase his capital.

Despite his great size and forceful personality, Pierce did not settle disputes with his fists. He once said, “By Heaven, sir, if I was to stop to fight with everybody who cussed me, I would be fighting all the time—but while they’re busy cussing me, I am busy getting their money.”

Pierce was involved in one affair that a Texas historian later called “just plain murder.” Shanghai had hired three Lunn brothers to work for him on one of his ranches, but they were discovered by a ranch hand killing some of Pierce’s cattle for their hides and tallow. When informed, Pierce led a vigilante lynch mob of seventy-five men who captured the Lunns and two other accomplices. When Shanghai found a load of some 450 hides with his brand on them, he reportedly ordered all five offenders to be hanged from the next tree.

In 1871, Shanghai sold out of his cattle interests for $110,000 and moved temporarily to Kansas City, perhaps to escape legal proceedings related to the hangings. He also managed to avoid a young Texas gunslinger, John Wesley Hardin, who had recently shot six men and who had in the Civil War fought with the Lunns and was looking for Shanghai for revenge.

After a mixed record of investing in banks and other enterprises in Kansas City, Pierce returned to Texas in 1873 with a vengeance. He began to buy up cheap land along the Texas coast, eventually owning more than 250,000 acres, and his brother Jonathan accumulated many acres as well. Shanghai built a plantation style home that exists today on the Pierce Ranch in Wharton County. He founded a town nearby that exists today, named Pierce. Along the way he achieved a long-held goal—he surrounded the ranchland of W. B. Grimes, forcing his former employer to move to north Texas, which at the time was still threatened by raiders from the Comanche tribe. Shanghai then remarked, “all accounts are squared.”

When the northern trails began to open, Shanghai became one of the largest trail drivers in Texas. He was one of the first to use the legendary Chisholm Trail. His steers became known as Shanghai Pierce’s “sea lions.” He was apt to introduce himself in his booming voice, “By heaven, sir, I’m Shanghai Pierce, Webster on cattle! (likening himself to the wordsmith and dictionary author Noah Webster). Eventually, Shanghai no longer accompanied the drives on horseback, but met his herds at Dodge City.

In his later years, after branching out investing in banks and railroads, Shanghai toured Europe and Asia to find a breed of cattle resistant to the ticks so prevalent in the Gulf Coast area. He returned, convinced that Brahman cattle were the most likely to be immune. But Pierce died before he could conclusively prove it. His nephew travelled to India and imported the first Brahman cattle into Texas, fulfilling Shanghai’s wishes and introducing to Texas this important breed.

In June of 1900, Pierce’s business interests suffered a loss of more than $1 million of damage from the great Galveston hurricane that wrecked the Texas coast. Still, he donated $80,000 for the relief of Wharton County residents.

On December 26, 1900, the legendary cattleman died of a brain hemorrhage at the age of sixty-seven. His tombstone is a life-sized sculpture of himself standing on top of a fourteen-foot column, all of which he had constructed in 1891. When asked why he had commissioned the statue, he had replied, “Sir, if I don’t do it myself, they will forget about Old Shang.” The Rhode Island-born Shanghai Pierce is still remembered today as one of the legendary cattleman of early Texas.

For further reading:

In 1953, a full-length biography was published by the University of Oklahoma about Shanghai’s life, by Chris Emmett, called Shanghai Pierce: A Fair Likeness. A copy is held by the Brownell Library at Little Compton.

The Brownell Library at Little Compton also has a folder containing newspaper and magazine articles about Shanghai, several of them published in The Cattleman magazine. One of the better articles in the file is “Shanghai’s Legacy,” by Mike Blakely, in the January 1986 edition of True West magazine.

Christian McBurney thanks smallstatebighistory author Tim Cranston for bringing to his attention the extraordinary life of Shanghai Pierce.

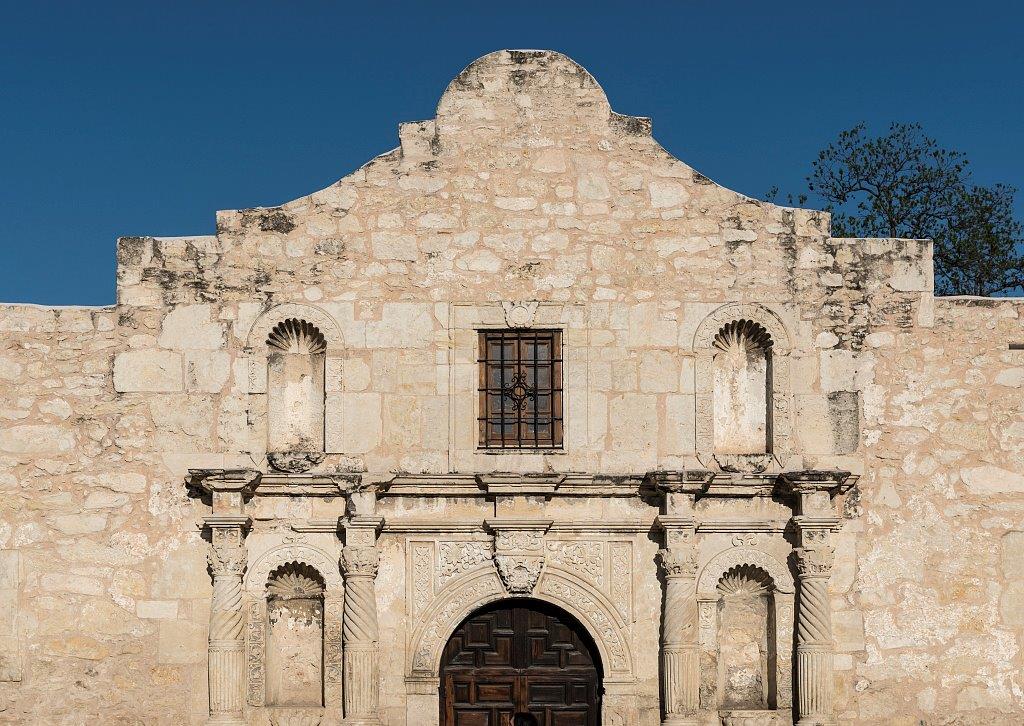

[Banner Image: The doorway of the Alamo, in San Antonio, Texas, built in the eighteenth century as a missionary church]