Rhode Island has a unique history, to say the least. And here comes another history book showcasing said unique history. Russell J. DeSimone has been for decades one of Rhode Island’s premier private collector of Rhode Island books and ephemera. In this new book, he makes available for readers 254 images spanning two centuries of Rhode Island election ballots. While most of the ballots depicted are drawn from DeSimone’s collection some are from the Providence Public Library’s Special Collections. Years earlier DeSimone and the late Daniel Schofield cataloged images of more than 650 election ballots while listing nearly another 1,000 paper ballots from the Rhode Island Historical Society’s collections.

At the back of dustjacket DeSimone notes about the paper election ballots, “In a sense, they are all artifacts of how our American democracy works. Indeed, they are the very building blocks of democracy.” Interestingly, their use allowed Rhode Island voters to, in effect, vote remotely on election day, rather than travel to the state’s capital to vote in person.

The book is also a tour of Rhode Island history. When times were conflicted, there tended to be more and different election ballots. The election of 1860, when Abraham Lincoln ran as the nominee of the Republican Party, was one such time. In addition to Stephen A. Douglas representing the Democrats, there was the “Union Conservative Ticket.” The electors named on this ticket intended to vote for a candidate considered as a more moderate Union supporter than Lincoln—John Bell. Two of the electors from Rhode Island named on this ballot were substantial owners of textile mills that manufactured cloth intended for sale in the South, Amasa Sprague of Cranston and Samuel Rodman of South Kingstown. Rodman’s son, Isaac Peace Rodman, would become a Brigadier General in the Union Army and ultimately be shot and killed by enemy fire at the Battle of Antietam in September 1862.

In the 1860 elections, state and local elections were also in ferment. William Sprague, a young and wealthy textile magnate, was nominated by the Democratic Party for governor of Rhode Island. Seth Padelford of Providence was nominated by the state’s Republican Party for governor, but many Republicans felt he was too “radical”—meaning too much of an abolitionist who might help rush the northern states into war with the South. So in addition to the Democratic Party ticket, there are ones supporting Sprague for the “Conservative Republican Ticket,” the “Conservative Union Ticket” and the “Young Men’s Convention” ticket. As DeSimone writes in his book, “The combination of Democrats, conservative Republicans, and others was too strong for the Republicans to overcome, and Sprague defeated Padelford.” Fortunately, Sprague would prove to be a strong supporter of the Union cause. I was also interested to see that in post-war years, Padelford ran for governor and was elected.

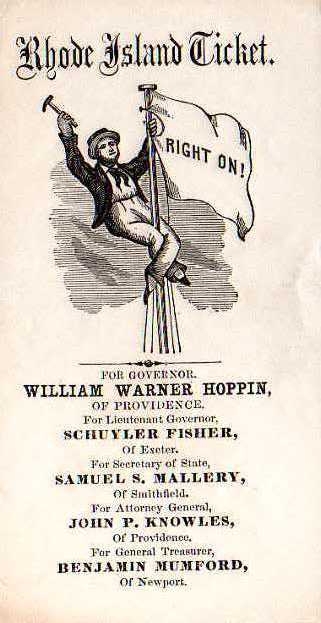

One of the best images of the lot is shown in the lower left-hand corner of the from of the book’s dustjacket. It shows a common man having scaled a flagpole, wielding a hammer and about to pound the last nail into a flag that reads “Right On!” No, this election ballot is not from the 1960s; it is for candidates who supported the temperance movement in 1854.

This book is highly recommended for students of Rhode Island history, as well as for state and town libraries and historical societies.

You can purchase the book by clicking on this link:

https://ripublications.org/selected-titles/

For the reader’s benefit, here is a short history of election ballots penned by Russell J. DeSimone, which is from the book’s Preface:

Providence was founded in 1636 by Roger Williams; in 1643 Williams obtained a patent from the British government giving powers of self-government to the towns of Providence, Portsmouth, and Newport. By 1647 Warwick was added and the government was organized at Newport. In 1663 King Charles II granted a charter to John Clarke creating the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, setting boundaries and creating a government document by which the colony was to be governed until 1843, when the first written Constitution was approved.

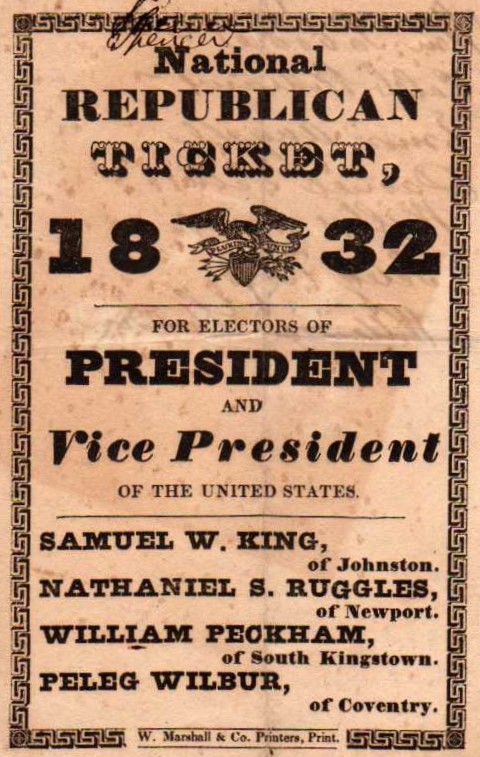

Initially, freemen were required to travel to Newport, the capital, to cast their votes for general officers. At this time voters were most likely given blank pieces of paper which they filled in the name of the candidates. Because traveling to Newport created hardships, especially during sowing and harvest times, a system of proxy voting was created. Each April in town meetings the freemen were allowed to cast a vote which was then sealed, packaged, and taken to the capitol in Newport and counted on Election Day in May; those candidates with a majority were elected to office.

It is believed that Rhode Island was the first colony to provide its voters with a printed ballot, known as a “prox.” The earliest known Rhode Island prox is dated either 1743 or1744 [1] and is located at the Rhode Island Historical Society. John Russell Bartlett in his Dictionary of Americanisms noted “The use of these words [prox or proxy] is confined to the State of Rhode Island. Prox means the ticket or list of candidates at elections presented to the people for their votes.”[2] Those ballots or proxies contained a list of candidates for Governor, Lt. Governor, ten assistants (upper house of the Assembly), Secretary, Attorney General and Treasurer. The freemen were allowed to cross-out a candidate and write in a substitute.

Starting in the Revolutionary period, proxies often contained slogans which were printed at the top; examples include “Liberty, Property & No Stamps” and “LANDHOLDERS! Beware; be firm and persevere: For united we stand, divided we fall!” The Rhode Island lower house of the legislature was elected semiannually in April and August from the various towns.

A few years after the printing of the first prox, political factions developed in the colony. The development of one of the most noteworthy battles between factions was known as the Ward – Hopkins political controversy. The noted political historian Jackson Turner Main stated that “Rhode Island produced the first two party or more accurately two-faction system in America.” The leaders of the two factions were Samuel Ward of Westerly and Stephen Hopkins of Providence. Ward’s support came from the southern part of the colony with its center in Newport, whereas Hopkins’ support came mainly from the northern part of the colony with its center at Providence. Some of the issues and differences included taxes, debt and paper currency. During the struggle between these two factions, Hopkins was elected governor ten times and Ward three times. This controversy ended when both sides agreed on the same candidate Josias Lyndon (who served as governor from May 1768 to May 1769) and both Ward and Hopkins retired as candidates. Ultimately, both Hopkins and Ward went on to represent Rhode Island in the Continental Congress.

Rhode Island political factions did not end with the Ward Hopkins period; during the War of 1812 Federalist battled Republicans; in the 1830s an anti-Masonic faction emerged; and following the Dorr Rebellion of 1842, a Law & Order coalition made up of Whigs and conservative Democrats formed to counter the pro-suffrage movement. Special interest in elections continued in the 1850s with the advent of the temperance ticket; during the 1860s the pro-Union ticket formed; and by the 1870s and 1880s the Greenback Party and the Prohibitory factions manifested themselves. It is an everyday fact of life that in a democracy politics will always be with us, creating new factions.

This election ticket for the 1832 U.S. presidential election shows the name of the party (National Republicans) and the electors from four Rhode Island towns

In the early colonial years and prior to the use of printed ballots, freemen voted by voice in town meeting or on blank pieces of paper, affixing their name to the back of the paper. Over time, political parties supplied the freemen with printed proxies. By virtue of the freemen signing their names to the proxies it precluded any secret vote.

These printed election artifacts are the subject of this study. With any election comes the possibility of fraud and abuse. Almost every election was preceded with a warning to the voters in the local newspapers of fraudulent election tickets being distributed to dupe the voter, and after almost every election the same newspapers carried accounts of stuffed ballot boxes or of wholesale buying of votes by unscrupulous politicians. To curb these problems the Rhode Island General Assembly passed a law at its March 29, 1889 session which effectively adopted an Australian type of secret ballot in envelopes. The first section of the law read:

Section 1. All ballots cast in elections for electors of president and vice-president of the United States, representatives in congress of the United States, general officers of the state, and members of the general assembly, and all ballots upon any proposed amendment to the constitution of the state submitted to the electors for approval, after the first day of June, in the year eighteen hundred and eighty-nine, shall be printed and distributed at public expense, as hereafter provided. The printing of the ballots and instruction sheets, and the delivery of them to the several cities and towns, shall be paid for by the state. The distribution of the ballots to the voters shall be paid for by the cities and towns respectively.

With the passage of this law, the role of election tickets in Rhode Island ended except for their continued use in local elections.

(Historian Lauareate Patrick T. Conley, in the book’s Introduction, provides a short but penetrating overview of the development of Rhode Island colony and state voting laws).

This “Rhode Island Ticket” was for a slate of elected state officials. The party supported Temperance!

Notes:

[1] Howard M. Chapin, “Eighteenth Century Rhode Island Printed Proxies”, page 54-591, in The Americana Collector; John E. Alden, Rhode Island Imprints 1727-1800 (New York: R.R. Bowker Co., 1949), x and 26. [2] It should be noted that Connecticut also used the term prox or proxy but it referred to an election or election day and not to the paper ballot.