Abraham Lincoln came to Rhode Island at least three separate times but never as President of the United States. In September 1848, Lincoln stopped in the capital city of Providence after riding a considerable distance in a railcar on his way to a Whig party convention in Worcester, Massachusetts. After a brief layover — there is no historical evidence that he ever disembarked — his train departed to its intended destination. Then in 1860 and now a member of the newly formed Republican Party, Lincoln made overnight stops in the state. During these visits campaigning for the Nation’s highest office was foremost on Lincoln’s agenda as was the timely opportunity to visit his son Robert Todd, a student at the prestigious Phillips Academy in Exeter, New Hampshire.

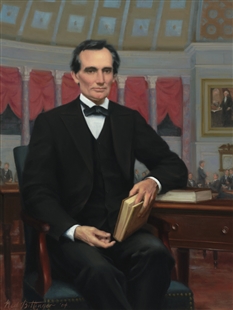

Abraham Lincoln as he would have appeared as a member of the House of Representatives from 1847-49, by Ned Bittenger, 2004 (House of Representatives)

Initially, Lincoln planned to speak about the country’s most pressing issue of slavery to an audience in Brooklyn, New York. The talk was eventually moved from Brooklyn to Cooper Institute in Manhattan to accommodate a larger audience, which would include such notables as William Cullen Bryant, Horace Greeley, and David Dudley Field. Knowing the difficult challenge that lay ahead in his campaign due to his limited political exposure outside the Midwest, Lincoln spent nearly three days honing his speech before actually delivering it on February 27, 1860.

When Lincoln arrived at the Institute, his physical appearance surprised many in attendance. He was unlike anything the spectators had imagined. An attendee described him as follows:

Mr. Lincoln was a tall man about 40 years of age, clothed in dark clothing with a black silk cravat, over six feet in height, slightly stooping as tall men sometimes are, with long arms, which he frequently moved in gesticulation, of dark complexion with dark almost black hair, with strong and homely features, with sad eyes, which moved in earnest argument or quiet humor, and then assumed a calm sadness . . .

Soon, however, his words overwhelmed the influential crowd. His speech that day became a classic and today is celebrated as Lincoln’s Cooper Union Address. With methodical reasoning, a persuasive argument and a no-nonsense delivery, his remarks catapulted him to national prominence in the days and weeks that followed; the American press enhanced his rising image with glowing articles about his talk. Arguably, his most memorable words that evening were given in his closing statement: “Let us have faith that right makes might, and in that faith, let us, to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it.”

The following morning, Lincoln departed Manhattan by train passing northeast through Connecticut and into southern Rhode Island before arriving in Providence late in the afternoon. He was just in time for a dinner engagement at the homestead of Mr. John Eddy, a prominent Rhode Island lawyer and local Republican who accompanied Lincoln on the train. Eddy had recruited Lincoln to speak in Providence while both were in New York. Hours later, Lincoln spoke to an audience estimated at 1,500 on the second floor of Railroad Hall at the northern end of the Union Passenger [The 1848 building, once touted as the longest of such type in America, has long since been razed and the Federal Courthouse at Kennedy Plaza is now situated on the site. A bronze plaque is visible on the building (corner of Exchange Street and Fulton Street) commemorating Lincoln’s appearance]. Lincoln’s speech that evening was said to be a repeat performance of the previous evening. Unfortunately, the hall was not large enough and many were turned away though a contingent of students from Brown University did gain access. Among them was William Ide Brown. Five years later while fighting for the Union, he was killed at Petersburg.

After an introduction by Honorable Thomas A. Jencks, Lincoln took the floor. His opening remarks alluded to items he had read in a newspaper while travelling by train to the city. The speech was slightly different from the one he gave at Cooper Institute the previous evening, but according to local press, there appeared to be many similarities. His oration lasted two-and-a-half hours and, unfortunately, no transcription of his talk has been found. As was to be expected, Lincoln’s words met with mixed reviews, depending on the political persuasion of the local press. The Republican newspaper, The Providence Daily Journal, commended his efforts while the more conservative democratic newspaper, The Providence Daily Post, was less than kind. Neither commentary came as a surprise. By most accounts, gains were made by Lincoln that evening that swayed more citizens from Rhode Island to his side of the slavery argument: that he and his party were against the expansion of slavery in the territories and that slavery could not be defended by the U.S. Constitution.

Following his successful speech, Lincoln spent the remainder of the day at the home of his host, in a house located in a residential neighborhood on Washington Street. Mr. Eddy, a merchant and prominent lawyer in Providence, was the brother-in-law of Charles T. James, owner of a number of cotton mills and a former Democratic U. S. senator from the state. Meeting Mr. Eddy’s wife must have been a pleasure, but encountering Eddy’s four-year old child, Alfred, may have been better. Lincoln loved children and always seemed prepared for such occasions. Fetching a handful of red gumdrops from his pocket, he handed them to the young boy. The thoughtful gift made a lasting impression on Alfred. As years passed and Alfred grew old, his memories of Lincoln’s visit remained crystallized in his memory.

Mr. Eddy, being a tall man, had a bed manufactured to fit his elongated proportions. Lincoln was extended the privilege of sleeping upon the bed that night. When awakened in the morning, Lincoln was quick to compliment his host on the comfortable arrangements [A dated account states that the bed Lincoln slept in and the chair where he sat was preserved by descendants of the family]. No doubt, this bed was an exception to the rule when he hit the campaign trail.

After his Providence speech, two Woonsocket businessmen—Lattimer W. Ballou, founder of the Republican Party in Rhode Island and Edward Harris, a Rhode Island industrialist—approached Lincoln about speaking in their city on his return trip from visiting his eldest son Robert in New Hampshire. Lincoln savored the opportunity to expand his political base in Rhode Island. Realizing he was somewhat of an unknown quantity in New England and being politically savvy, he accepted the invitation.

The following morning Lincoln woke and boarded a train to Boston. From here, he travelled to New Hampshire, where he visited Robert at Phillips Academy.

Upon his return trip by rail, Lincoln’s journey took him through Providence, but he never disembarked. After a brief layover, the train departed for New Haven, Connecticut, where Lincoln gave another speech. But, as promised, in less than a week, Lincoln returned to Rhode Island to deliver a rousing speech at Harris Hall in Woonsocket, now the site of City Hall. Little is known about the content of his talk but accounts allude to similarities to his Cooper Union oration. A noted Woonsocket manufacturer, Darius Farnum, noted in his diary soon after the speech: “Presidential campaign for Republican party for 1860 opened in Woonsocket tonight by Honorable Abraham Lincoln of Illinois – a very tall spare man.” After the speech, Lincoln spent the night at the Harris house. In commemoration of the speech, a bronze plaque similar to the one in Providence has been affixed outside the entry door of the building. The following day, March 9th, Lincoln left Rhode Island for his home in Springfield, Illinois. He never returned to the state, but might have had it not been for an assassin’s bullet.

As for the young child who was given gumdrops by Abraham Lincoln, he grew up to attend Brown University (Class of 1879) where he became the first captain of the football team. Three years after graduation he founded the Mercantile Mutual Fire Insurance Company serving on the board of directors until his death. During his lifetime, Eddy relished the opportunity to reminisce about his childhood meeting with the future president. How much he accurately remembered about Lincoln’s visit to his homestead is questionable. What he had seen that day may have been retold and reinforced by his parents as he grew older. Arguably, he certainly had an interesting tale to relate during his lifetime. Alfred Updike Eddy lived to a ripe old age, passing away three months shy of his 81st birthday.

Today, a statue of President Abraham Lincoln can be seen in Roger Williams Park, Providence. The monument is the only effigy of Lincoln in the entire state.

[Banner Image: Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, by George Healy, 1869 (National Portrait Gallery)Bibliography:

The reader is encouraged to learn more about Lincoln’s visits to Rhode Island by viewing Christopher Martin’s transcript in the book by John Williams Haley, The Old Stone Bank History of Rhode Island, Vol. III (Providence: Providence Institution for Savings, 1939), pages 224-227.

Additional sources for this story include: “Lincoln and Rhode Island – Abraham Lincoln’s Classroom,” “Abe Lincoln’s Visits to New Bedford, Taunton Recalled by Deacon James N. Dunbar,” and “The Rhode Island Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission Final Report” of June 30, 2010, by Abraham Lincoln Scholar, Frank J. Williams, Chairman, all of which can be found online by searching the names of the author and title. Honorable Frank J. Williams also provided a comprehensive account of Lincoln’s visit in “A Candidate Speaks in Rhode Island: Abraham Lincoln Visits Providence and Woonsocket, 1860,” Rhode Island History, Volume 51, Number 4 (Nov. 1993). This Rhode Island History article is arguably the finest work regarding Lincoln’s visits to Rhode Island.