The present Beavertail Light Station, with its 1856 granite light tower and two almost identical white painted brick keeper’s houses is located on Rhode Island’s Conanicut Island in the middle of lower Narragansett Bay. It is officially termed a “Light Station” by the U.S. Coast Guard. Its location on Beavertail Point is south of the village of Jamestown at the very southern tip of a peninsula connected to the main island by a narrow two-lane causeway road named Beavertail Road.

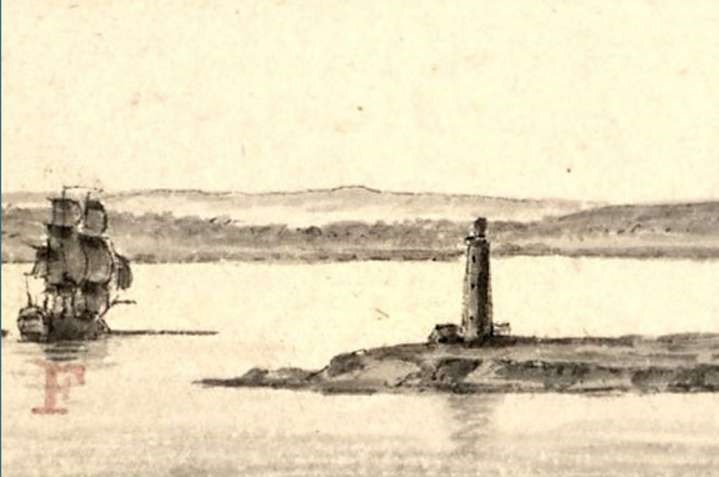

Excerpt from a drawing by French artist Pierre Ozanne, probably in August 1778, during the siege of Rhode Island, showing a French warship rounding Beavertail Point and heading toward the West Passage. The drawing is one of the only surviving ones showing the 1753-built Beavertail Lighthouse. [Library of Congress)

At the turn of the 18th century, navigation was not an exact science nor did a ship’s navigator have accurate instruments or astronomical references to place the vessel’s exact position on a chart. The charts of the day were suspect in terms of accuracy and the cartographer often made assumptions when joining lines of shore features. It was the responsibility of the ship’s master to keep the ship and its cargo safe and not foundering on an uncharted rocky shoal.

The risks associated with the sea were a way of life. Shipwrecks were common along the coast. Navigation aids did not exist. Local knowledge of the rocks, shoals and reefs was revealed only after loss of life, cargo and the ships themselves. Because nighttime passages through uncharted waters were even more precarious; the prudent captain would wait off shore until identifiable land marks became visible.

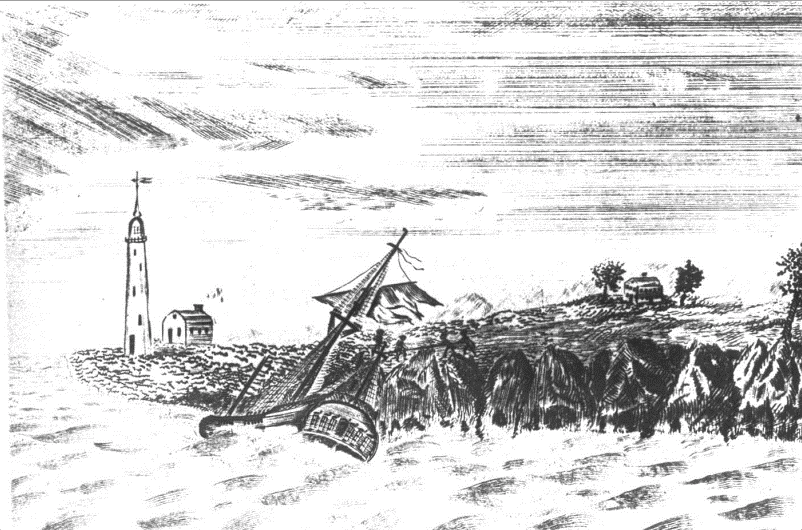

Also sketched by French artist Pierre Ozanne, in 1789. It was found in Paris’s Louvre art museum (Author’s Collection)

With accumulating losses of vessels and cargo, the marine insurance business took hold. Well known Rhode Island colonial businessmen, including Moses Brown, Stephan Hopkins, John Gerrish and Joseph Lawrence, began underwriting “risks at sea.” William De Wolf of Bristol also took up the business of underwriting the risks. Although insuring ships and cargo against “the dangers of the sea” was profitable, the losses and delays suffered by merchants, ship owners, and underwriters overwhelmingly led to the recognition of a need for navigation landmarks.

The approach to Newport and Narragansett Bay is represented by a wide body of water called Rhode Island Sound. It stretches for thirty-three nautical miles from the eastern side of Block Island to Noman’s Land, an obscure island off the western coast of Martha’s Vineyard. Just off center of an imaginary line between these two islands and perpendicular to it, sixteen miles to the north, lies the entrance to Narragansett Bay. The depth of water gradually decreases from about 150 feet to 75 feet. While measuring depth to determine position was and still is a significant navigation method, rock hazards around the Bay’s entrance rise abruptly, giving no warning until it is too late.

The primary threat sailing into the entrance of Narragansett Bay was and still is the dangerous Brenton Reef. This underwater cluster of rocks stretches out to the southwest from Brenton Point for three-quarters of a mile. In calm weather it is noticeable by a mild swell or heaving of the sea. During a strong southeasterly gale, water breaks over the reef and a mile of white water exposes the line of rocks.

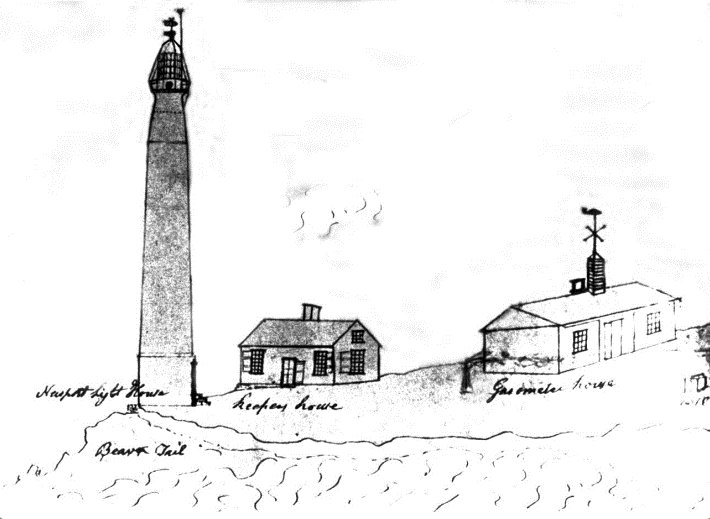

David Melville’s 1817 successful “Gasometer” (coal gas variant) installation at Beavertail Light (Author’s Collection)

Less than a mile to the east of Brenton Reef is Seal Ledge, an underwater hazard with a depth of just twelve feet of water above it. Two miles west of Brenton Reef, just to the south of Beavertail Point, lies another hazard, the fabled Newton Rock, with less than six feet of water over it. It too has been the downfall of mariners attempting to cut short the passage around Beavertail Point.

From April to October fog developing over the entrance to Narragansett Bay added another hazard. Once it arrives, fog usually prevails anywhere between four to twelve hours. But sometimes periods of fog last from four to six days with only brief clearing intervals brought on by dry northerly or westerly winds.

By 1710 Newport had turned itself into a major maritime center, becoming one of the five major ports in America along with Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston. Maritime commerce began to boom. Its growth spilled over into surrounding towns on Narragansett Bay. Trade and the export of rum, candles, horses, cheese, fish, furniture, silver, and other value-added goods were the main engines of economic growth during the 18th century. Activities inextricably linked to Newport’s participation in the slave trade and widespread ownership of slaves by well-to-do families in the city were fueled by the shipping magnates.

Although the slave trade’s famed Triangular Trade had a focus point in Europe, mainly with English ship owners, Newport’s entrepreneurs jumped right into this lucrative trade. Slavery was then deemed legal and morally acceptable and ships were readily modified to carry human cargo. Traders bought enslaved Africans in exchange for goods shipped from Europe and the American colonies. From Newport, rum, candles, dried fish, furniture and silver products were shipped to Europe and Africa. The second part of the triangle (“the Middle Passage”) was the voyage of captive black Africans across the Atlantic to the Caribbean and the Americas. Those Africans who survived a terrible journey were sold to work on plantations, typically in the British Caribbean and the American South. The third part of the triangle was the return voyage to Europe or to American colonies with sugar, molasses, tobacco, and coffee, derived from crops made profitable by slave labor. The triangular trip could take up to a year to complete. With molasses Rhode Island distilleries could make rum and start the trade again.

The origin of Beavertail Light was tied directly to the slave trade. The protection and safety of ship traffic into Newport Harbor aligned itself to this 18th century economic engine as surely as Rhode Island ships ruled the American slave trade traffic for more than seventy-five years. In 1730 half of the wealthiest residents of Newport and Bristol were involved in the slave trade. The safety of ships and preventing their loss translated to profit, and the influence of the wealthy made the demands of a lighthouse at Beavertail impossible to ignore.

By 1725 regular slave voyages from Newport around the “triangle” were being recorded. There actually was competition between English-based slave ships whose owners had larger vessels with greater sized crews than the colonists. Some estimates claim Rhode Island ships made over 1,000 voyages from 1725 to 1807 carrying over 100,000 human chained cargo even though slave trading was outlawed in Rhode Island in 1787. At its peak, Newport was the home port of 184 slave ships doing business via the triangle trade, including ships of the families of John and Moses Brown from Providence and Aaron Lopez the largest taxpayer in Newport at the time.

Newport was the hub of New England’s slave trade, and at its height, slaves made up one-third of its population. Business was so good that in February of 1707 the colony laid down an impost tax of three pounds for each negro imported. Newport merchants also participated in the more mundane carrying trade, taking foodstuffs to the British West Indies and the South. By 1774 the waterfront bustled with activity with over 150 separate wharves and hundreds of shops crowded along the harbor between Long Wharf and the southern end of the harbor. Rhode Island during the 1750s with its thirty legitimate distilleries exported thousands of gallons of rum. Some reports considered Newport as the fourth richest city in America.

According to the early records of Jamestown’s proprietors, the idea of a light at Beavertail goes back to 1705 when a watch house built and manned by local Indians required a chimney. A Jamestown Town Council Member, Gershom Remington, then aged twenty-two, at a meeting on June 9, 1712 went further and issued a resolution “to warn the Indians to build a beacon as soon as possible at Beavertail.” He also ordered Benedict Arnold (this Arnold was the son of the past governor of Rhode Island, the first owner of the land at Beavertail and great grandfather of the famous Revolutionary war traitor of the same name) “to look after the watch and see that it be faithfully kept.”

It is clear that there was a priority then to repair the watch house and maintain a standing watch at Beavertail. One reason was to keep any eye out for marauding pirates and, during King George’s War, enemy French warships. Actually, at no time prior to the Revolutionary War did a hostile vessel actually enter Narragansett Bay, nor was there any record of purposeful destruction of shipping or property. Thus, the purpose of the beacon, watch house and the scheduled watches were likely for the purpose of guiding vessels into Narragansett Bay, fulfilling the functions of the present-day lighthouse. While not in the accepted form of a lighthouse constructed of brick and mortar, it was nevertheless established purposely to look seaward. While no such record of its actual configuration exists, it is likely that an open pit fire on stone ruble or brazier was constructed next to the “Watch House.”

Accordingly, the 1712 light at Beavertail certainly can profess to being the “first tended” navigation light in America. It was not, however, a lighthouse structure but a beacon. The later Boston Light, since it had a lighthouse structure, might be said to the be first lighthouse in North America. The controversy on that score is likely to continue.

The merchants and ship owners in Newport must have been responsible for persuading the Jamestown Town Council to provide the pre-1705 watch house and later its 1712 associated beacon. It was their gain or loss that a navigation aid was placed or not placed into operation at Beavertail Point.

At the time, Conanicut Island to them, while providing some agricultural products for maritime trade, more importantly had Beavertail Point, the ideal location for a navigational aid to protect their ships and maritime interests. As early as 1739, thirty-seven years before the Revolutionary War, Newport merchants operated more than 100 large ships yet lacked a navigation aid to guide them into harbor. In 1749, the year the light was constructed, 160 ships were cleared for foreign voyages and by 1769, throughout the Narragansett Bay area over 200 vessels were engaged in foreign trade and another 300 to 400 used in coastal traffic.

Newport town records state: “A committee was appointed to build a light house at Beavertail on the island of Jamestown, alias Conanicut ,as there appears a great necessity for a lighthouse as several misfortunes have happened recently for want of a light.” They went on to say, “whereas there is a necessity of building a light house at Beavertail, which will be of singular service for vessels coming into the harbor in the night season and prevent great damage which is occasioned for the want thereof.”

With that directive, a committee was formed to manage the construction of the new lighthouse at the very southern tip of Beavertail on a rock ledge less than fifty or so feet from the edge of the sea. The builder and architect selected was none other than Peter Harrison, the famed architect of such Newport jewels as the Redwood Library, Touro Synagogue, and Brick Market, as well as Kings Chapel in Boston and dozens of colonial buildings throughout the British North American colonies.

Four years later in July 1753, the lighthouse structure was destroyed by fire. The cause was never explained but apparently it was not due to inattentiveness by keeper Abel Franklin who lived next to the lighthouse. After the fire disaster, no time was lost in replacing it. This time it was authorized by the colony’s General Assembly and in August its members voted to erect a new light using stone or brick. The material was gathered from the colony’s Fort George on Goat Island, which over the years had, on and off, been fortified as threats appeared from Britain’s foreign enemies. Harrison again designed the new structure, which was built by William Reed. The new light took some time to complete and during its construction Keeper Abel Franklin diligently displayed an ordinary lantern to help ships identify the point.

The tower was rebuilt and fitted with a respectable light composed of fifteen individual lamps, each with a conical reflector. Two groups, one of seven lamps and the other of eight lamps were mounted on three-foot diameter copper tables. The lower eight lamps “illuminated every point on the horizon, while the upper seven lamp configuration, the vacant space towards the land.” From a navigational point of view, why the land space was illuminated is not understood but perhaps the description of the lighting arrangement was not accurately stated. In any case, keeper Franklin must have had his hands full each night tending the fifteen lamps that required filling, trimming of wicks, and cleaning smoked up chimney windows.

The plaque reads: “Foundation of the Original Beavertail Lighthouse Erected 1749. Third Lighthouse to be established in the Atlantic Coast.” Note the compass recently added on the top, showing true north (Christian McBurney)

The Revolutionary War and demands of the General Assembly to spend money on wartime operations resulted in major renovation or improvements to the light at Beavertail being deferred. Newport, as a major port and located at the entrance of Narragansett Bay, was a target of British military planners.

In December 1776 the British landed 7,000 troops in Newport as part of its plan to quell the uprising of the Colonists. British forces also occupied Conanicut Island, considered necessary to protect the entrance to the East Channel leading to Newport. Two battalions of Hessian soldiers were the first regiments stationed on Conanicut Island, and cannon were brought to Fox Hill two miles to the north of the lighthouse. The British undoubtedly used the light at Beavertail for safe passage of their own vessels, although most residents of Conanicut Island had fled. British troops remained in Newport and on Conanicut Island for three years.

In late July 1778, Admiral Comte d’Estaing and a large fleet of French warships appeared at the entrance of Narragansett Bay. After several of d’Estaing’s ships forced their way up the West Channel, the British evacuated Conanicut Island. In the evacuation, the British removed much of the lighting apparatus from the Beavertail lighthouse. The joint French and American effort to dislodge the British from Newport failed in late August 1778, and the British reoccupied Conanicut Island.

There is no known image of the original 1749 lighthouse. The only images of the early 1753 lighthouse were drawn by French officers in d’Estaing’s fleet.

The British evacuated Newport and Conanicut Island in October 1779. Before doing so, on October 20, the British set fire to the long-standing mast, light tower and other woodwork, and removed much of the lighting apparatus. The British believed destroying the lighthouse could confuse American and French vessels that would later sail into Newport or up Narragansett Bay to Providence, Bristol and Warren.

The lighthouse was rebuilt and placed back in operation, remaining in use until the present lighthouse granite block tower was built in 1856.

The new Colonial Congress of the United States wasted no time in recognizing the importance of lighthouses and the economic role they played in the safety of shipping. The ninth law passed by this new congress addressed the need for bringing lighthouses under the umbrella of the federal government. The 1789 law created the “U.S. Lighthouse Establishment” and took over the jurisdiction of America’s twelve lighthouses then in existence. Beavertail, previously under the administration of the new state of Rhode Island, was transferred in 1790 on the books of the federal government by note from President George Washington to Alexander Hamilton, Secretary of the Treasury.

Rhode Island, fearing a loss of revenue and the inability of the new government to maintain the light, hesitated to finalize the formal transfer. It did not officially deed the property to the United States until 1793, and then only with the proviso, “that if the United States shall at any time hereafter neglect to keep it lighted and in repair, the grant of said lighthouse shall be void and of no effect.”

The federal government fulfilled its obligation at Beavertail lighthouse. Moreover, the original twelve lighthouses nationwide grew dramatically to 70 in 1822, and by 1852 over 330 lighthouses were operational in the country under federal government control.

The author’s book Beavertail Light Station On Conanicut Island continues the history of the light, its keepers and various developments from 1793 to the present day. The book is available in the Beavertail Lighthouse Museum gift shop and through Amazon books (see link to the right of this article).

Beavertail Light Station remains an active navigation aid under U.S. Coast Guard management. The light and fog signal were automated in 1972 and all personnel previously working at the site were relocated. Since 1993 the non-profit Beavertail Lighthouse Museum Association (www.beavertaillight.org) operates a free museum during the summer months and maintains the historic property under agreement with Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management and a license with the U.S. Coast Guard.

The Beavertail Lighthouse and Museum, located on one of the prettiest spots in the state and is perhaps the state’s best small museum (Christian McBurney)

Only the rock and limestone foundation remains as an artifact of the early lights on which both the 1749 and the 1753 light were constructed upon. In 2013 the crumbling foundation was restored and a compass rose embedded on top, meticulously aligned to “true north” using modern day instruments. The bearing line coincidentally intersected within one-half of a degree perpendicular to the north-facing octagonal side, a testament to Peter Harrison’s architectural and building skills.

[Banner image: The plaque reads: “Foundation of the Original Beavertail Lighthouse Erected 1749. Third Lighthouse to be established in the Atlantic Coast.” Note the compass recently added on the top, showing the direction of true north (Christian McBurney]

Sources

For the original and secondary sources used in the preparation of this article, see bibliography for Varoujan Karentz, Beavertail Light Station On Conanicut Island (BookSurge Publishing, 2008).

For the destruction of the light by the British in October 1779, see Johann Prechtel Diary Entries, Oct. 12-23, 1779, in Bruce Burgoyne (ed.), A Hessian Officer’s Diary of the American Revolution (Bowie, MD: Heritage Press, 1994), 37-38 & 164-66; Johann Conrad Dohla Diary Entry, Oct. 21, 1779, in Bruce E. Burgoyne (ed.), A Hessian Diary of the American Revolution (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1990), 112-13; Thomas Hazard Diary Entry, Oct. 20, 1779, in Caroline Hazard (ed.), Nailer Tom’s Diary … (Boston, MA: Merrymount Press, 1930), 11; Jeremiah Greenman Diary Entry, Oct. 11, 1779, in Robert Bray and Paul Bushnell (eds.), Diary of a Common Soldier in the American Revolution, 1775-1783 (DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois Press, 1978), 142; Providence Gazette, Oct. 23, 1779.