Book Review:

Dark Work, The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island

by Christy Clark-Pujara (New York University Press, 2016)

Precious little was ever published in the nineteenth century on Rhode Island’s role in either the slave trade or slavery in general. It was not until the mid-twentieth century that the subject was addressed in any detail. Published works by such authors as Irving H. Bartlett (The Story of the Negro in Rhode Island, 1954), Jay Coughtry (The Notorious Triangle,1981), Robert J. Cottrol (The Afro Yankees: Providence’s Black Community in the Antebellum Era, 1982), and Robert K. Fitts (Inventing New England’s Slave Paradise, 1998) come to mind.

In 2006 Brown University published a report, Slavery and Justice, the resulted in an investigation by a select committee looking into the university’s role in the slave trade and slavery. In 2007, Charles Rappleye published his groundbreaking work, Sons of Providence: The Brown Brothers, the Slave Trade, and the American Revolution. Since the 2006 report and Rappleye’s book, we have had to wait another ten years for a book to tackle the topic that has been painfully difficult for many to accept. Perhaps it is because many wish to believe that slavery only took place in the South and Rhode Island’s involvement was at most minor.

Now along comes a new book to address the subject head-on and in a comprehensive manner. Dark Work, The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island, by Christy Clark-Pujara is the first full length study that unveils the extent of the state’s involvement in slavery since the Brown University report. More than any other of the original thirteen colonies and states along the Eastern Seaboard, Rhode Island plied the triangle trade transporting more slaves to the Americas than all the other states combined, and at the time of the American Revolution Rhode Island had the largest proportion of slave population of any of the New England colonies. Clark-Pujara, Assistant Professor of History in the Department of Afro-American Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, uses economic history to investigate how Rhode Island played such a significant role in the business of slavery. The book is not overly long, with just 197 pages of text, but it is well researched and footnoted with nearly 600 endnotes. Strangely, the publisher did not permit the author to include a bibliography, but the sources are all in the endnotes. For a history buff endnotes are often as important as the text.

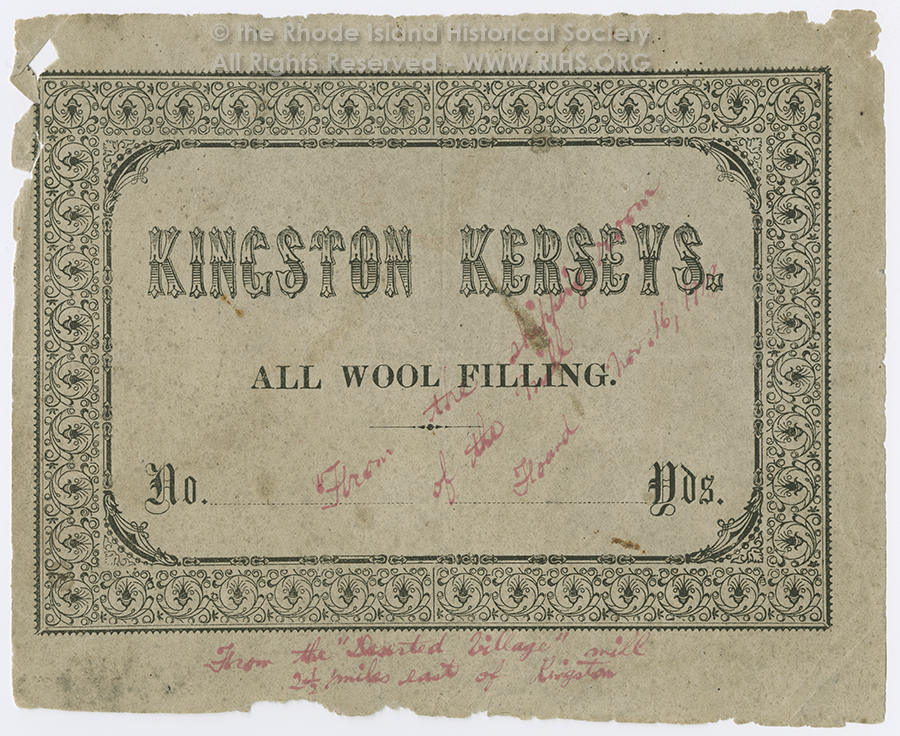

Fabric label. Kingston Kersey All Wool Filling, no date, Ephemera Collection, Box 4, Rhode Island Historical Society. RHi X17 2824. The mill that made the label was probably at Mooresfield, about 2 1/2 miles east of Kingston.

Clark-Pujara’s book not only examines the business of slavery but also how enslaved and free blacks in Rhode Island responded to the socioeconomic forces about them. As she noted at the end of her Introduction “The history of Rhode island must include their stories because they too shaped Rhode Island and the United States.” Her work spans a considerable period of time in so short a book, addressing everything from early seventeenth century colonial laws pertaining to slavery to laws enacted in the aftermath of the Civil War. She looks at how enslaved and free blacks supported the West Indies trade with the production and exportation of Rhode Island products like lumber, beef, pork, butter, cheese, crops, candles and horses in exchange for sugar and molasses, as well as black labor in the rum making and ship building trades in support of the Atlantic slave trade.

Following the end of the slave trade, the author moves on to discuss the role of Rhode Island textile mills and the manufacture of “negro cloth,” a course wool-cotton material used to clothe slaves in the South. She observes that seventy-nine percent of these textile mills manufactured slave clothing. This seems like an extraordinarily large percentage and for what is an economic history I would have liked to have seen more discussion on this topic. The author could also have discussed more the textile business in general considering that all products coming out of these mills was done using cotton grown on the slave-based plantations of the American South.

The book has six easy-to-read chapters. While it is primarily a history book it also helps shed light on race in America today, especially chapter four, “The Legacies of Enslavement” and chapter five, “Building a Free Community.” It includes a study of the African colonization movement, including one led by Newport Gardner. Chapter four provides an excellent look into the poor laws that plagued the state’s disadvantaged, especially blacks, in ante-bellum Rhode Island. While these laws also did not much help poor whites either, their failure fell particularly hard on newly-freed slaves trying to succeed in a market economy with no inheritance or saved wealth. Also provided is a discussion on the Providence race riots of 1824 and 1831. Tension between the races, then as now, was an important undercurrent in all aspects of everyday life. Chapter five discusses the various black institutions that developed during this time period providing insight into how an oppressed portion of the community found the strength and resiliency to survive in an unwelcoming society. The author notes that prior to her book “no single monograph explores the history of black people in Rhode Island from slavery to freedom.” It seems to follow that there is also a need for a comprehensive history of blacks in Rhode Island following the demise of slavery up through the end of the twentieth century.

The last chapter of the book addresses the Dorr Rebellion, school segregation and black troops in the Civil war, essentially touching on the topics of black suffrage, school integration and the role of the Rhode Island 14th Regiment (Heavy Artillery) in the Civil War. While the discussion on the Dorr rebellion is good, it does not cite the most definitive work about this episode in Rhode Island history, The People’s Martyr by smallstatebighistory contributor Erik Chaput. Also lacking was mention of the fact that Rhode Island was the only state to re-enfranchise blacks in the ante-bellum North—something that the state got right. The discussion on the struggle for school integration, led by Newport’s George T. Downing, is especially well done, as is the discussion on the role of black military units in both the Dorr Rebellion and the Civil War.

The book’s conclusions are worthy of note. While I disagree with Clark-Pujara’s assessment that without slavery Brown University would not have existed, it is worth contemplating. She also brings up excellent points in righting the wrongs of the nation’s past alluding to a need for more public memorials, more affirmative action in education, and concern for racial disparities in mass incarceration. Dark Work is an unvarnished recounting of the painful past and while addressing the role of only one state it does raise the issue of race across the nation. Read it for its history or read it for its insight into today’s race issues but do READ IT!