Over the course of the last 25 years, Salve Regina University historian John F. Quinn has produced a remarkable body of scholarship illustrating the ethnic and religious history of the United States. While certainly (and sadly) not popular today within the historical profession, one simply cannot understand American history without understanding the intersection of religion and politics. In his first book, Father Mathew’s Crusade: Temperance in Nineteenth Century Ireland and Irish America (2002), Quinn brilliantly chronicled the career of one of the 19th century’s most prominent temperance advocates and the intersection of the debate over alcohol consumption within the political culture.

Over the next several decades, Quinn published dozens of highly influential articles including, “‘The Nation’s Guest?’: The Struggle between Catholics and Abolitionists to Manage Father Theobold Mathew’s American Tour, 1849-1851,” U.S. Catholic Historian (Summer 2004), “Expecting the Impossible?: Abolitionist Appeals to the Irish in Antebellum America,” New England Quarterly 82 (December 2009) and “From Dangerous Threats to “Illustrious Ally”: Changing Perceptions of Catholics in Eighteenth Century Newport,” Rhode Island History 75 (Summer/Fall, 2017).

In his most recent book project, The Rise of Newport’s Catholics: From Colonial Outcasts to Gilded Age Leaders, Quinn brilliantly weaves together state and national history to present an engaging narrative covering the late 18th century to the early 20th century, highlighting the unique religiously tolerant Newport community. Overall, the book addresses the ecclesiastical maturing of Catholicism in Rhode Island and the role Catholics played in the development of a political culture that would last well into the 20th century.

Quinn is to be praised for his learned and succinct discussions of key moments in American history and their impact on Rhode Island history, including, among others, the impact of the French Revolution, Thomas Jefferson’s 1807 Embargo Act, the often-forgotten national tour conducted by President James Monroe, the Irish Potato Famine, the rise of the anti-Catholic Know-Nothing Party, and the impact of the Civil War on Newport.

Quinn opens with several chapters on Rhode Island’s liberal acceptance of people of different religious backgrounds, including Quakers, Baptists, Jews, and the Moravian Brethren, as well as a discussion of Newport’s sentiments concerning religion during the Revolutionary era. While the colony openly embraced many religious faiths, it still harbored an especial distrust of Catholics, a legacy from the English roots of the colonial settlers. This is evidenced by the annual celebration of Guy Fawkes Day, a reminder from the distant past of the famed Gunpowder Plot of 1605 in which a small group of English Catholics attempted to blow up Parliament.

Anti-Catholicism and Patriot sentiment often went hand-in-hand in the 1760s and 1770s, especially after the passage of the 1774 Quebec Act. The latter act was the British government’s attempt to preempt any dissatisfaction among the French-Canadian population by restoring French civil law and allowing Catholics to hold public office. As Quinn notes, according to many Patriot Protestants, “Parliament was expressly encouraging the spread of popery on their [American] northern and western borders” (17). Indeed, “popery and British tyranny” were seen as the “twin evils” (20).

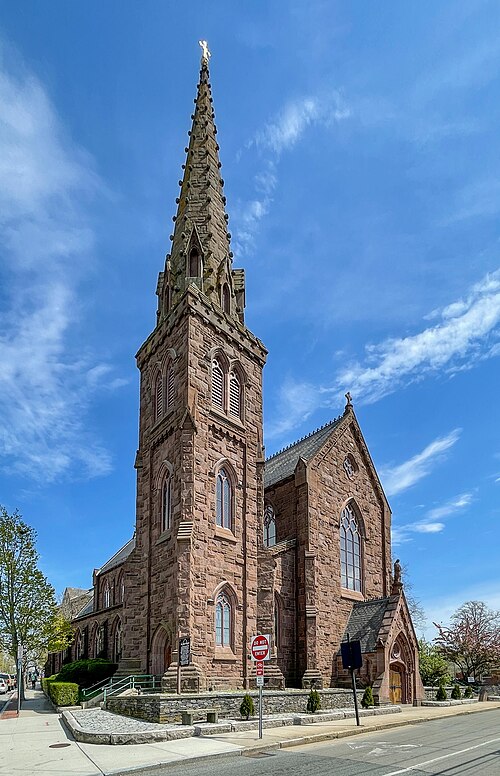

St. Mary’s Church, with an official name of Church of the Holy Name of Mary, Our Lady of the Isle. John and Jaqueline Kennedy were married here on September 12, 1953, in a service presided over by Archbishop Richard Cushing and attended by more than 800 guests.

Yet the arrival of thousands of allied French troops to Newport for almost a year starting in the summer of 1780 served to change the outlook of town residents towards the Catholic faith. When the French Army under the command of Comte de Rochambeau arrived, they brought twelve Catholic chaplains, two of whom were Irish. Newport’s Colony House served as the state’s capital, but space was made for a hospital, and a room was set aside to serve as a Catholic chapel. Quinn makes good use of excerpts from contemporary diaries especially those of Newport’s clergy showing the evolution of sentiments towards Catholics.

As the Catholic community slowly began to develop in Newport at the end of the 18th century into the 19th century, Quinn chronicles the protracted construction of Fort Adams by Irish laborers. In 1828, a chapel on Mount Vernon and Barney Streets served the Irish laborers. In addition, the new chapel also served wealthy Catholic summer residents, including socialites Catherine Harper, her daughter Emily Harper and her foster-daughter Catherine Seton, the daughter of the future Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton.

Soon Newport would cater to wealthy New Yorkers and Bostonians, along with prominent southerners. National political leaders John Calhoun, Millard Fillmore, Franklin Pierce, and Henry Clay all summered in Newport.

In August 1837, Bishop Fenwick of Boston dedicated the first Catholic Church in Rhode Island on Barney Street in Newport. The church was built on the first land ever owned by Catholics in Rhode Island and was placed under the patronage of St. Joseph. The first Saint Patrick’s Day Parade in the state occurred in Newport in March 1842, just as the debate over Thomas W. Dorr’s attempt at extralegal political reform was heating up. In 1849, the cornerstone for a new church, Holy Name of Mary, Our Lady of the Isle, was laid.

By 1861, at the start of the Civil War, Newport, as Quinn notes, was a changed city. The U.S. Naval Academy moved from Annapolis, Maryland, to Newport, so that the city gained a sizable number of midshipmen to replace the men who had gone off to war. The famous historian George Bancroft, the founder of the academy, had a summer home on Bellevue Avenue and knew the city well. Quinn’s discussion of the impact of the Fenians in the 1860s, a secret organization of Irish Nationalists, will be of interest to students of the state’s history.

After the war, tourism quickly returned to Newport. In August 1869, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony held a women’s suffrage convention in Newport at the Academy of Music and the recently completed Opera House. The famed abolitionist and women’s rights advocate Frederick Douglass addressed a packed house.

By the mid-1880s, the Vanderbilts, the Astors, along with wealthy Catholics, such as Countess Annie Leary and Emily Havemeyer, built elaborate summer “cottages” in Newport overlooking the Atlantic Ocean. The Navy also expanded its presence in the Ocean State with the establishment of the Naval War College in 1885. Quinn’s last chapter, “Irish, Italian and Portuguese: Catholic Prominence in Post World War I Newport” explores the impact of the city’s multi-cultural Catholic experience.

John Quinn’s deeply researched book is a must-read book for students of the state’s history. His work serves as a nice companion to historian Eve Sterne’s Ballots and Bibles: Ethnic Politics and the Catholic Church in Providence (Cornell University Press, 2004), Robet W. Hayman’s monumental multi-volume history of the Diocese of Providence (1982-2020), and historians Patrick Conley’s and Matthew Smith’s 1976 work, Catholicism in Rhode Island.