The name of North Kingstown’s own Captain Daniel Fones might be spoken in the same breath with as Thomas Tew, William Kidd, and Blackbeard. Fones’s skills as a sailor, his savvy as a maritime tactician, and his bravery at the helm were just as legendary as these three pirates. Fones’s abilities were well-known and he was just as feared by the French and Spanish as the other three. The only difference between good Captain Daniel Fones and the three somewhat dastardly captains here-to-fore mentioned was a crucial one: Fones served as a “privateer” and never once crossed the rather loosely defined line to be a pirate that the others did. He never moved from acting as a privateer (a marauding sea captain acting under a legal license from a recognized government), toward piracy. Piracy was essentially the same thing as privateering but with legal authority—and a pirate had no limits, except self-imposed ones.

Daniel Fones was born in 1713 on Conanicut Island, in Jamestown, to Jeremiah and Martha Fones. While he was still a boy his family moved across the Bay to North Kingstown and settled in a home built on the Boston Post Road near its intersection with the Devil’s Foot Road. He took to a life at sea early on, and by the age of twenty-seven achieved his masters rating and became a captain. Around this time, the colony of Rhode Island, concerned about French and Spanish maritime marauders and invaders during latest war between Great Britain and France, called King George’s War, commissioned the construction of a warship named the Tartar. It would be the sailing vessel that Fones would command into history.

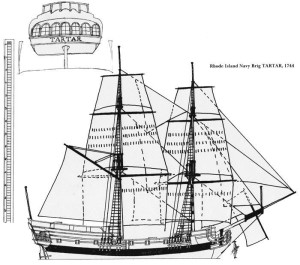

The Tartar was launched in May of 1740. Rhode Island’s governor, Richard Ward, described it as “a fine sloop of 115 ton burden, armed with 12 carriage [cannon] and 12 swivel guns [smaller deck guns] . . . furnished with small arms, pistols, and cutlasses to defend us against the enemy should we be attacked. She’d make a fine privateer able to fight a hundred men on her deck.” The Tartar’s first master, Colonel John Cranston, took her to sea in June of 1740. With a full crew, they captured their first prize, the French merchant schooner Société bound for the French Canada. The Tartar convoyed 200 Rhode Island soldiers in the disastrous attack on Cartagena in modern Colombia. Captain Benjamin Wickham took the helm in 1741, followed by Captain Philip Wilkinson in 1743. In June of 1744, it was Daniel Fones’s turn; he was commissioned by the colony of Rhode Island to take the helm of its primary warship.

Fones’s first assignment with Tartar was defensive in nature. He was tasked to join the warship belonging to the colony of Connecticut and patrol the coastline between Long Island and the western tip of Martha’s Vineyard. The Rhode Island crew was to be awarded the standard reward for privateersmen should they capture a vessel: one eighth of the value of the prize for the captain, one quarter divided into equal parts for the other officers, and five eighths, again divided equally, for the remainder of the crew. If a ship was successful in capturing enemy commercial and military ships, both officers and sailors could earn a good profit.

In late February of 1745, the Tartar was ordered to join warships and troop ships from the colonies of Connecticut and Massachusetts Bay in what would become known as the Louisbourg expedition. This was a major effort by New England colonies to seize the impressive French fortress on Cape Brenton Island. In early April, this convoy was on its way north, but was spotted by the powerful 30-cannon French war frigate Renommée. The French came hard at the convoy, hoping to crush the invasion before troops could even land. Fones and the Tartar peeled off from the group and took on the stronger French warship. To open the contest, Tartar fired two broadsides at the Renommée and the French gunners responded with four broadsides in return. Both vessels suffered damage, but the tactician in Fones knew he needed to keep the Renommée clear of the convoy. He tauntingly trimmed sails and took off, daring the French to follow. The French captain took the bait, expecting to overtake the Tartar and quickly finish her off. Fones was the better and faster sailor and lost the Renommée after an eight hour chase. Meanwhile, the convoy made it safely to its rendezvous, accomplishing Fones’s main task. The next day, the Tartar returned, damaged but with Fones still eager to help. The Louisbourg expedition, nearly ending in disaster before it could begin, was saved by Fones’s quick action and thinking. It would not be the last time that Fones exhibited his outstanding skills as a ship captain.

The Tartar joined British, Connecticut, and Massachusetts Bay warships in the blockade of the harbor at Louisbourg, trying to starve out the French troops stationed in the port, and in supporting the landing of the New England invasion force in the vicinity. In May Fones and the Tartar captured the large French merchant ship Deux Amie, which was loaded with goods meant to resupply Louisbourg. Fones’s share of this prize was handsome indeed. In June, during an engagement known as the Battle of Famme Goose Bay, the French, along with their Iroquois allies, tried to reinforce their compatriots trapped at Louisbourg. They came under the cover of night in two sloops, two schooners, a shallop, and between fifty and one hundred Indian canoes to relieve the forces at Louisbourg. They French and Indian forces surrounded and attacked the Connecticut warship Resolution and threatened to overwhelm it. All was nearly lost and it looked as if the French and Iroquois were going to be successful until, around the bend, sailed Fones on the Tartar. The ship made quick work of the invaders, and according to Connecticut officer William Sheffield, “Captain Fones probably decided the fate of Louisbourg, for if this large force had fallen upon the rear of the New England soldiers and thus placed them between the fire of the two opposing forces, they would probably have had to end the siege.” Two days later, on June 17, the dispirited French in Louisbourg, with no more hope, surrendered. Fones was one of the heroes of the day in New England.

Fones and the Tartar stayed on near Louisbourg after the surrender to help defend this new important British post. New Englanders were thrilled with the news that the long-time French menace had been put out of action and were proud that colonists had played the major role in seizing it. It was an historic achievement, indeed. Fones remarked in a letter back to Governor Ward that he was pleased to be able to walk down Louisbourg’s main streets as an Englishman. After the fortress fell, the Tartar helped guard it against French efforts to recapture it and occasionally seized a French vessel as a prize. Fones and the Tartar were Rhode Island’s main contribution to the victory: the colony finally sent 150 soldiers to help in the siege, but they arrived too late, and had to serve as part of an occupation garrison.

Eventually, Fones and his ship were called back to Narragansett Bay to continue patrolling between Long Island and Martha’s Vineyard. In July of 1745, Fones and his crew captured another large French merchant ship, the Heron, and he collected his one-eighth share. October came around and the combined governors of the colonies called on him to take the Tartar on a reconnoitering voyage up the coastline because they had heard rumors of French warships in the vicinity. Finally in November, after this long and arduous term of service, he was relieved as commander of the Tartar by Captain Peter Marshall. The hero of Louisbourg returned home to North Kingstown.

Although Fones at this point was finished with the Louisbourg expedition, with the war between Great Britain and France raging on, he was not done with his days of Crown sanctioned privateering. In May of 1747, he was back in charge as master of the Tartar, plundering and harassing both French and Spanish shipping, as well as patrolling his old haunts between the easternmost tip of Long Island and the westernmost end of Martha’s Vineyard. A year later in May of 1748, he walked down the Tartar’s gangway for the final time. A few months later he sauntered up the gangway of the larger privateer Prince Frederick as the second officer. The following year he was commissioned as her captain, a position he held, raiding and marauding all the while, until a terrible snow squall forced the vessel on rocks off of Block Island in March of 1751. He returned home to North Kingstown after this harrowing brush with death.

With the onset of the French and Indian War in 1754, Fones was back at sea again with a new privateering commission from the Crown, commanding the privateer Defiance in 1756 and 1757. Then he commanded the privateer Success until 1760. The then 47-year-old ship captain and swashbuckler put down his sword and sextant for good and retired from a life spent mostly at sea.

When Fones returned to his farm on the Boston Post Road, he enjoyed life on land with his wife Mary, his daughters Mary, Martha, and Elizabeth, and his son and namesake Daniel Jr. He represented North Kingstown for a time in the General Assembly, and then in 1770, started a third phase of his remarkable life, when he turned over the homestead farm to son Daniel and, taking some of his privateering gains, constructed a large and impressive tavern house in Wickford, just up the road a piece from the waterfront. The Daniel Fones Tavern was the first “watering hole” any sailor would come to after leaving his sailing vessel tied up at the docks or anchored just offshore in Wickford Harbor. There may not have been a better place in all of New England to lift a flagon of ale or throw back a taste of fine Rhode Island rum, while listening to tales of the Louisbourg expedition and privateering on the high seas, told with a flourish by former ship captain and now tavernmaster Daniel Fones, one of Rhode Island’s early military heroes.

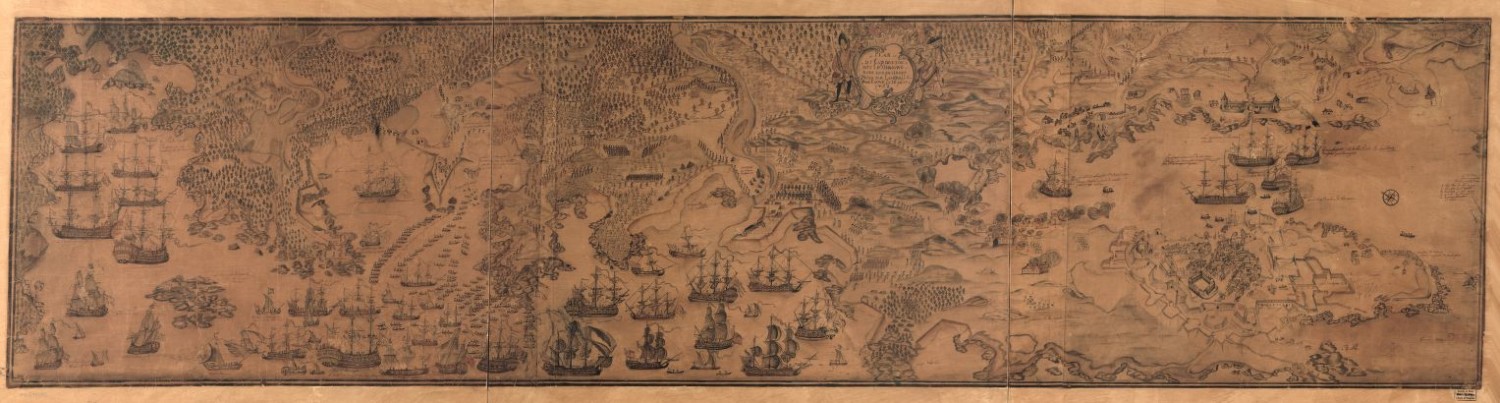

[Banner image: French map of Louisbourg and its environs in 1758 (Library of Congress)]Bibliography

Town of North Kingstown Vital Records

Town of North Kingstown Land Evidence Records

Chapin, Howard M., The Tartar: The Armed Sloop of the Colony of Rhode Island (The Society of Colonial Wars in Rhode Island, 1922)

James, Sydney V., Colonial Rhode Island: A History (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1975)