[The authors dedicate this article to their friend and mentor Patrick T. Conley, the dean of Rhode Island historians.]

From 2010 to 2015, the publishing world was alive with scores of books and articles in commemoration of the sesquicentennial of the Civil War. Editors at the New York Times created the Disunion website, tracking day-by-day events of the Civil War and publishing scores of articles on all aspects of the war. However, the Disunion series came to an end not long after the 150th anniversary commemoration of the Union victory at Appomattox in April 1865. Unfortunately the important story of reconstruction — how the war-torn nation was put back together amidst a set of revolutionary changes in the meaning of freedom in America — was not thoroughly covered in the series.

Until 1861, the protection of individual civil and political rights had rarely been seen as the nation’s business. By the winter of 1864-65, however, abolitionists, who were growing in their political influence argued that the nation needed to take an active role in protecting the privileges and immunities of citizenship for black Americans. Those abolitionists who continued to push only for emancipation were branded as conservatives. Indeed, the issue of federally enforceable political and civil rights for blacks emerged as a radical litmus test. One of the most fascinating stories of the Reconstruction is the drafting of the 15th Amendment, which in its final form declared unequivocally that the “right of the citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged … on account of race, color or previous condition of servitude.”[1] However, as historian Patrick T. Conley argues, an often overlooked aspect of the story involves Rhode Island’s unique contribution to the final wording of the Amendment, a contribution that severely limited the rights of naturalized citizens and, somewhat unintentionally, created an avenue for southern state governments to disenfranchise a black population the amendment had sought to protect.

The complex questions in the wake of Appomattox were actually issues that had been part and parcel of Rhode Island politics for decades. Twenty-three years earlier, Providence attorney Thomas Wilson Dorr led the state into near civil war over the question of equal rights and equal suffrage.[2] Ironically, at the heart of much of the conversation in Rhode Island regarding the 15th Amendment was the same $134 figure required to vote that Dorr attempted to remove. One banner in a large Suffrage Association parade in April 1841, referring to the fact that the relatively few citizens were voters in Rhode Island as a result of real estate ownership as a requirement to vote, derisively read: “Worth makes the man, but sand and gravel the VOTER.” By linking suffrage to citizenship, Dorr challenged the dominant 19th-century theory of citizenship. These issues assumed a position of importance in the wake of the defeat of the Confederacy.

At the heart of the debate lay two questions: Did the destruction of slavery automatically make freedmen and women citizens? And was suffrage a prerogative of citizenship?[3] During the Reconstruction period, naturalized citizens in Rhode Island were still required under the state’s constitution to be in possession of $134 of ratable property before they could vote. For most naturalized citizens the property requirement was an impossible figure to meet. In the 1840s, Thomas Dorr had hoped the federal government would step in and declare Rhode Island’s government “unrepublican” and allow the People’s Constitution to go into effect. Advocates of suffrage reform during Reconstruction once again hoped the federal government would step in and ensure the right of suffrage for all citizens in Rhode Island. “If the national government can make itself felt in South Carolina or Texas, or other of the Southern States, it surely can in Rhode Island,” declared the editor of the Providence Evening Express.[4]

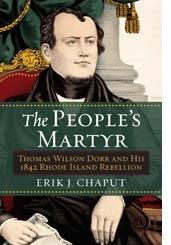

What is remarkable about the Reconstruction era in Rhode Island is that the same groups that had been inspired by Thomas Dorr’s ideology, found inspiration in the platform of the radical Republicans. Dorr’s attempt at extralegal reform inspired women, throngs of abolitionists, both black and white, and the laboring poor to clamor for their rights. Dorrite women, led by Catherine Williams, Ann Parlin and Frances Harriet Whipple Green, for example, were some of the first women in American history to publicly advocate for franchise reform.[5] A new group of female reformers emerged during Reconstruction, but their message was the same. “We intend to canvas our little state thoroughly during the next few months, and when our wise men sit in council next winter, we expect to show them that not one in ten, but one half at least of our R.I. women, and all of our best men desire a government based on the principles of the Declaration of Independence,” wrote the abolitionist and suffrage reformer Elizabeth Buffum Chace (Figure 1) in 1869 in the National Anti-Slavery Standard.[6] Two years earlier, drawing from the U.S. Congress’ efforts to enfranchise blacks in the South, Chace headed a drive to petition the Rhode Island General Assembly for the right to vote for women (Figure 2). We “are compelled to obey laws the making of which we have no voice,” wrote Chace.[7]

Figure 1. Elizabeth Buffum Chace was the foremost leader of the woman’s suffrage movement in Rhode Island and championed the passage of the 15th Amendment regardless of its exclusion of women (Russell J. DeSimone Collection)

As she did with the Suffrage Association in the 1840s, Chace drew heavily upon the revolutionary ideology embodied in Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence. However, the debate over the 15th Amendment led to a schism in the women’s suffrage movement in Rhode Island and between white and black abolitionists. Those women who felt the amendment should not be endorsed because it excluded females remained within the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) under the state leadership of Paulina Wright Davis. In the 1840s, female abolitionists, such as the fiery Abby Kelley of Worcester, who made frequent trips to Rhode Island, advocated for black voting rights at the expense of their own. During Reconstruction, those who favored passage of the amendment, despite its shortcomings, split from the NWSA and formed the American Woman Suffrage Association under the state leadership of Elizabeth Buffum Chace.[8]

Figure 2. Rhode Island Women’s 1867 Petition to General Assembly requesting an amendment to the state constitution to allow women the elective franchise (RI State Archives)

While the ranks of female reformers were split in the 1870s, abolitionists were nearly unanimous in favor of the 15th Amendment. Rhode Island abolitionist and civil rights leader George T. Downing, for example, declared in January 1869 at the National Convention of the Colored Men of America that the work of the U.S. Congress needed to be directed towards securing “some final measure of equal and universal suffrage, without any discrimination on the ground of race, color, previous condition or religious belief.”[9] Downing managed the restaurant in the U.S. House of Representatives and used it as a platform for his lobbying. In the 1860s, Downing led the drive to desegregate Rhode Island’s public schools.[10] Though he did not mention Thomas Dorr by name, Downing drew directly from the People’s Governor’s ideology. Central to this ideology was the argument that every state in the Union was guaranteed a republican form of government through Article IV, section 4 of the Constitution — the so-called “guarantee clause.” Similar to Dorr, Downing argued that at its most basic level a “republican form” of government was one that included the “cardinal idea” that the people “have a voice as to who shall rule over them.”

The Rhode Island Senate, controlled by Republicans, voted in favor of the 15th Amendment in late May 1869, but voting in the lower chamber was delayed until January 1870. Republicans in Rhode Island were divided over the amendment not because of the issue of race but because some feared the Irish could be considered a race and that the state’s property qualification for naturalized citizens to vote could be deemed discriminatory. The amendment was finally ratified by the Rhode Island House of Representatives on January 18 by a vote of 57 to 9 with most Democrats voting in opposition.

In the spring of 1870, shortly after national ratification, a petition containing 3,400 signatures was presented to the U.S. Congress (Figure 3) asking that the amendment be enforced in Rhode Island.[11] The movement was spearheaded by the Irish Catholic immigrant Charles Gorman (Figure 4), a member of the General Assembly from North Providence, and Providence Mayor Thomas Doyle. As historian Eric Foner has argued, “In a reversal of long-established political traditions, support for black voting rights now seemed less controversial than efforts to combat other forms of inequality.”[12]

The post-Civil War era in Rhode Island witnessed massive economic transformation and raised the level of fear among native-born Protestants as immigrant Irish Catholics crowded into the state’s growing cities.[13] As Conley has documented, fear of a voting Irish Catholic population was central to conservative ideology in the mid-19th century.[14] By the 1870s, this fear was pervasive and as the Providence Morning Herald noted, some Rhode Island Republicans disliked the 15th Amendment, not because they feared blacks, who actually had been voting since 1843 in the state, but because they feared the Irish more.[15]

The language of Gorman’s petition drew directly from the Dorrites: “The undersigned citizens of the State of Rhode Island, humbly petition your honorable body to pass such appropriate legislation as may be found necessary to obtain for and secure to the citizens of the United States, residents in Rhode Island, all the rights, privileges, and immunities guaranteed to them by the Constitution of the United States.” Thirty years earlier, Aaron White, one of Dorr’s most loyal followers, noted that as “citizens of the Union” the “rights” of a majority of Rhode Islanders “have been in repeated instances most outrageously violated by the men in power beyond all question.” White hoped “some way might be found that would at least restore” these rights “under the national Constitution.”[16]

Indeed, what is most striking about Rhode Island political life in the middle of the 19th century is the continuity between the 1840s and the 1870s. Along with economic issues, ethnic and religious variables constantly influenced voting behavior. The following remarks by the editors of the Providence Evening Press could have easily run in the pages of the Providence Express, a pro-suffrage paper in the 1840s: “Exclusiveness must and ought to die out from our democratic government and institutions. Rhode Island will be redeemed, and at an early day. The native and the adopted citizen will enjoy their just and equal rights, and would have done so long ago but for the bigoted, exclusive representative money-bags, who never have and do not now care for the people except as they can use them for corrupt and selfish purposes.”[17] The Evening Press labeled the rabid anti-Catholic U.S. Senator Henry Bowen Anthony the head of the “King Charles Charter” party, a reference to the 1663 charter that was granted by King Charles II and served as the state’s governing document.[18] The charter with its severely restricted franchise was superseded in 1843 by a written constitution with its own restrictive franchise clause for naturalized citizens.[19] Anthony was also the long-time editor of the Providence Journal. In the 1840s, Anthony’s paper took a strong nativist stance against Irish immigrants and a strong anti-Dorr stance.[20]

An earlier version of the 15th Amendment put forth by Senators Henry Wilson (R-MA) and John Bingham (R-OH) actually contained language forbidding discrimination in terms of race, color, nativity, property, education, or creed.[21] Ironically, Wilson had been first elected to the Senate by a wave of nativist sentiment in the 1850s. Senator John Sherman (R-OH), the brother of the famed Civil War general, asked:

Why should we protect the African in the enjoyment of suffrage when in certain states of the Union even naturalized citizens cannot vote? Why should we protect the descendant of the African, when in certain states of the Union a man who has the misfortune not to be able to read and write cannot vote? Why should we apply this supreme remedy of the Constitution only in favor of this particular class of citizens? Senators must see at once that to rest this constitutional amendment on so narrow a ground is not defensible.[22]

However, in the end, as the Providence newspaper Manufacturers’ and Farmers’ Journal — the semi-weekly companion to the Journal and also under the control of Henry B. Anthony — noted: Congress did not “recommend an amendment that was designed to abolish all restrictions in the exercise of suffrage.”[23] In order to garner enough votes to placate their conservative colleagues, radical Republicans were forced to accept a narrow definition of suffrage. As Conley has asserted, Anthony “led the fight to limit the 15th Amendment to blacks (“race, color, or previous condition of servitude”) and left such oppressed minorities as the Irish Catholics of Rhode Island and the Chinese of California unprotected by federal law.”[24]

During the debate over the final language in Congress Boston abolitionist Wendell Phillips, a man not known for his compromising tendencies, urged a quick resolution in order to ensure an amendment to protect black suffrage was passed. “For the first time in our lives we beseech them [congressmen] to be a little more politicians — and a little less reformers,” maintained Phillips in an important editorial in the National Anti-Slavery Standard.[25] Phillips also spoke to the Rhode Island General Assembly and assured Republicans the amendment would not invalidate state suffrage regulations.[26] This position was a stark reversal from Phillips’s hard-line position in 1841 when he, along with William Lloyd Garrison and other prominent abolitionists, vehemently opposed Dorr’s People’s Constitution because it contained a whites-only clause. In 1870, the half-a-loaf approach to universal suffrage was now deemed acceptable. As a result of the final language of the amendment, the door was left open for state legislatures in the North and the South to adopt restrictive poll taxes and other measures to curtail the vote. With the passage of the amendment and equal rights seemingly secured, the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS), founded by Boston journalist William Lloyd Garrison in 1831, closed its door.[27] Garrison had ceased publication of his Liberator newspaper in 1865 after passage of the 13th Amendment.[28] Many Republican leaders shared Garrison’s view that the 15th Amendment had settled the issue of black voting and signaled the end of the party’s antislavery agenda. It was the Republican Party’s triumph—in terms of writing the idea of suffrage into the Constitution—that cities across the nation celebrated in the spring of 1870.

The streets of Providence were alive with excitement on the morning of May 18, 1870, as the state’s capital prepared for a “gala day and grand display” in celebration of the passage of the suffrage amendment. Reverend Augustus Woodbury remarked, “Suffrage is the greatest privilege given a man in matters of State. It is the great equalizer. The greatness of the privilege gives a sacred character and a priceless value to the ballot.”[29] The imposing procession through the streets of Providence was composed of a cross section of citizens, including Civil War military units, marching bands, and school children. The newspapers of the day noted the large number of black citizens in the procession, including “wagons containing representations from various Sunday Schools connected with colored religious societies” and “colored citizens on foot and in carriages.” Indeed, blacks throughout the country celebrated ratification. The Massachusetts 55th Colored Regiment, sister regiment to the more famous 54th Colored Regiment, for example, participated in a procession in the public park in Boston. A large parade of black Rhode Islanders, including former Civil War soldiers, started on Dorrance Street and wound its way through the East Side, concluding at Exchange Place. Garrison traveled south from Boston by train to deliver one of the major speeches of the day.[30] The citizens who were most eager to see how state and federal courts would interpret the transformative amendment however were not black Rhode Islanders, but white Irish immigrants. The day of the celebration the Democratic newspaper, the Providence Morning Herald noted under the caption, A Suggestion to the White Orators at the Celebration, “Men will join in this celebration who are the deadliest enemies of popular rights; they will assume the garb of patriotism and chant hosannas to the goddess of freedom, while their hearts are steeled against the rights of foreign born citizens. What consistency! Men preaching freedom in Georgia and trampling it in Rhode Island.”[31]

Figure 3. Charles E. Gorman’s 1870 Petition to Congress invoking both the 14th and 15th Amendments (National Archives)

In conservative Rhode Island, immigrant newcomers were deemed to be a threat to societal order. Bostonian and summer resident of Portsmouth on Aquidneck Island, Julia Ward Howe, the author of the Battle Hymn of the Republic, a leader in the women’s suffragette movement, and friend of Rhode Islanders Elizabeth Buffum Chace and Paulina Wright Davis, believed it would bring in the “Irish and German savage.”[32] Immigrants were primarily non-Anglo-Saxon, most were Celtic coming from famine-torn Ireland, while others were newly arrived from predominantly Catholic Germany. At all cost the old guard wanted to retain control of government and the idea of naturalized citizens being on an equal footing with native-born citizens was unconscionable [33]. With such closed-minded thinking could the 15th Amendment be used as a bridge to expand voting rights for immigrants? Certainly Charles Gorman and 3,400 others who signed a petition thought so as they sought to revive the work of the old Suffrage Association from the 1840s.

Figure 4. Charles E. Gorman, a representative in the state House of Representative, championed of equal rights for naturalized citizens. He would go on to serve as Speaker of the House in 1887-88 (Russell J. DeSimone Collection)

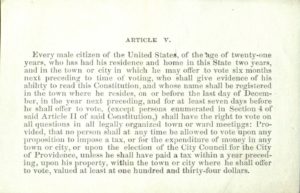

According to Gorman, it was unjust that a naturalized citizen could be elected to either branch of the United States Congress, and yet not be qualified to vote for himself when a candidate for election to the R.I. House of Representatives and not qualified to be elected to the legislature, or to vote for members of the legislature that would elect “him to the Senate.”[34] In October 1871, two reform-minded and one anti-Catholic constitutional amendments were proposed in the General Assembly. The first proposed, Article V (Figure 5), sought to remove the existing requirement that discriminated against naturalized citizens. However, in a popular vote, this amendment was resoundingly defeated by a vote of 6,560 against and only 3,256 in favor. A majority of voters clearly shared Anthony’s sentiment that it was best to keep the ballot from immigrants, “men who came upon us uninvited and on whose departure there is no restraint.” Imploring rhetoric from the Dorr Rebellion-era four decades earlier, immigrants were said to be “ignorant of our institutions, unacquainted with our form of government, embittered against all government, and ready with little solicitation to become the instruments of demagogues.”[35]

Figure 5. A proposed 1871 amendment to the state constitution allowing naturalized citizens the franchise on an equal footing with native born citizens failed to pass by a vote of more than 2 to 1. A similarly worded amendment (the Bourn Amendment) would readily pass in 1888 (Providence Public Library)

It took another seventeen years before a similar amendment, known as the Bourn amendment, put naturalized citizens on the same footing as the native born. By 1888, the time had finally arrived to accommodate naturalized citizens with the passage of Article VII (the Bourn Amendment) to the state constitution. This change of heart, initiated in the Republican-controlled General Assembly, did not come as an act of political kindness, but as an act of political astuteness. As Conley has noted: “Were Brayton and Bourn sincerely moved by the arguments and campaign of the friends of equal rights? Hardly! They simply looked at the results of the most recent Rhode Island state decennial census of 1885. It revealed that Rhode Island then had a population of 304,000 of which 125,000, or 41 percent, were of Irish stock. The real estate requirement for naturalized citizens was then much less effective as a weapon against the rising political influence of the state’s Irish citizens . . . The Republicans felt, quite correctly, that these ethnocultural groups could become political allies if they were given the vote immediately upon naturalization.”[36] Even though the 1888 Bourn Amendment removed many of the anti-democratic provisions of the 1843 Constitution, there was still a clause requiring ownership of $134 of real or personal property for voting on financial questions and in most city elections. These provisions would have to wait until the 20th century before they too were resolved.

[Banner image: A proposed 1871 amendment to the state constitution that would have allowed naturalized citizens the franchise on an equal footing with native born citizens (Providence Public Library)]

Notes

[1] See Patrick T. Conley’s detailed narrative, “No Landless Irish Need Apply: Rhode Island’s Role in the Framing and Fate of the Fifteenth Amendment,” Rhode Island History (2010), 79-90. See also Robert W. Hayman, “The Rhode Island Irish and the Civil War,” Rhode Island History (2015), 58.

[2] See Erik J. Chaput, The People’s Martyr: Thomas Wilson Dorr and His 1842 Rhode Island Rebellion (Lawrence, KA: University Press of Kansas, 2013). See also the Dorr Rebellion Project website: http://library.providence.edu/dorr

[3] See Erik J. Chaput, “The Reconstruction Wars Begin,” New York Times, February 1, 2015. See also Xi Wang, “’Make ‘Every Slave Free, and Every Freeman a Voter:’ The African American Construction of Suffrage Discourse in the Age of Emancipation,” in Manisha Sinha and Penny Von Eshen, Contested Democracy: Freedom, Race and Power in American History (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007), 117-140.

[4] Providence Evening Press, May 19, 1870

[5] See Russell J. DeSimone, Rhode Island’s Rebellion, Number Five, Post Rebellion Agitation for Suffrage Reform (Middletown, RI, Bartlett Press, 2009), 15.

[6] Quoted in Elizabeth C. Stevens, Elizabeth Buffum Chace and Lillie Chace Wyman (Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2003), 86.

[7] Petition on file at the Rhode Island State Archives. The authors thank archivist Ken Carlson for uncovering this important suffrage document.

[8] Stevens, 84-85.

[9] Proceedings of the National Convention of the Colored Men of America (Washington, D.C., 1869), 16. See also Patrick T. Conley’s “George T. Downing: Rhode Island’s Most Prominent African American Leader” at this website: http://smallstatebighistory.com/george-t-downing-rhode-islands-most-prominent-african-american-leader/

[10] See our essay on this website: “The End of School Segregation in Rhode Island.” See also Hugh Davis, “We Will Be Satisfied with Nothing Less”: The African American Struggle for Equal Rights in the North During Reconstruction (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2011).

[11] This petition can be found in the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

[12] Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877, updated edition (New York: Harper Collins, 2014), 447.

[13] Evelyn Savidge Sterne, Ballots and Bibles: Ethnic Politics and the Catholic Church in Providence (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004), 69-70.

[14] Patrick T. Conley, Democracy in Decline: Rhode Island’s Constitutional Development, 1776-1841 (Providence: Rhode Island Historical Society, 1977), 276-277.

[15] Providence Morning Herald, May 28, 1869

[16] Aaron White, Jr., to Dorr, March 30, 1844. Rider Collection (Box 8). John Hay Library, Brown University.

[17] Providence Evening Press, April 16, 1870.

[18] Ibid.

[19] See Patrick T. Conley’s analysis of the People’s Constitution and the Law and Order Constitution on the Dorr Rebellion Project website: http://library.providence.edu/dps/projects/dorr/pcon.php

[20] Patrick T. Conley, “The Constitution of 1843: A Sesquicentennial Obituary” published in Rhode Island in Rhetoric and Reflection (East Providence: Rhode Island Publication Society, 2003), 176.

[21] For the legislative history of the 15th Amendment in the 40th Congress see William Gillette, The Right to Vote: Politics and the Passage of the Fifteenth Amendment (Baltimore, MD: The John Hopkins University Press, 1969) and Earl M. Maltz, Civil Rights, The Constitution and Congress, 1863-1869 (Lawrence, KA: University Press of Kansas, 1990), 146-155. Herman Belz’s classic, Reconstructing the Union: Theory and Policy During the Civil War (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1969), provides a detailed discussion of the Congressional debate over suffrage.

[22] Congressional Globe (3rd session, 40th Congress, 1869), 1039.

[23] Manufacturers’ and Farmers’ Journal, March 22, 1869.

[24] Patrick T. Conley, Liberty and Justice (Providence: Rhode Island Publication Society, 1998) 359. Anthony had this to say in the U.S. Senate 1881: “Those that clamor on this matter from without the State are clearly meddling with what is not their proper concern; those within have mainly come from other States and countries, attracted by the advantages of a residence in Rhode Island, and belonging to a class which has been happily described as composed of men who came among us uninvited and on whose departure there is no restraint.”

[25] Quoted in James M. McPherson, The Struggle for Equality (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1964), 426.

[26] McPherson, 426-427.

[27] See Providence Evening Press, April 11, 1870.

[28] See Chaput, “Reconstruction Wars.”

[29] Providence Evening Press, May 19, 1870.

[30] Ibid. See also Xi Wang, The Trial of Democracy: Black Suffrage and Northern Republicans, 1860-1910 (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1997), 50-51.

[31] Providence Morning Herald, May 18, 1870.

[32] See Elizabeth Cady Stanton, ed., A History of Women’s Suffrage, 1861-1876 (New York, 1882), 335.

[33] Henry Bowen Anthony, “Limited Suffrage in Rhode Island,” North American Review 324 (1883), 118.

[34] Charles E. Gorman, “The Elective Franchise of Rhode Island,” November 1, 1879, p.30. This is pamphlet, on file at the Rhode Island Historical Society, is really an article written for the Select Committee in the U.S. Senate to inquire into alleged election frauds.

[35] Anthony, “Limited Suffrage,” 118.

[36] Conley, “The Constitution of 1843: A Sesquicentennial Obituary,” 177.