Civil War historians have long been citing that 620,000 American soldiers, North and South, died in the Civil War. In 2012, however, Dr. David Hacker of Binghamton University, using the latest available data, stunned the Civil War community by announcing that the number of dead is actually much higher, nearly 750,000. Based on census data, a careful look at the casualty rates among black and immigrant soldiers, and a review of filed pension applications, Dr. Hacker’s figure is widely gaining ground in the field as the most accurate estimate of the number of men who died as a result of their service. For the record, this historian agrees with Dr. Hacker’s figure, but concedes that the true number will never be known.

In his 1964 book, History of the Rhode Island Combat Units in the Civil War, General Harold Barker, a veteran of the First and Second World Wars, and whose grandfather served in the Civil War, recorded a total of 1,685 men from Rhode Island units who died as a result of their Civil War service. Because he did not footnote his book, it is unclear how General Barker reached this conclusion.

Immediately after the Civil War, the Rhode Island General Assembly appointed a committee of prominent Rhode Islanders, including Ambrose Burnside and John Russell Bartlett, to solicit and accept a proposal for a statewide monument that would list the names of every Rhode Islander who died in the “wicked Rebellion.” The monument, officially the Rhode Island Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument, would be inscribed, “Rhode Island pays tribute to the memory of the brave men who died that their country might live.” After a year-long search, the committee settled on a design from Randolph Rogers, consisting of a statue of “America Militant,” four bronze panels representing War, Victory, Peace, and History, as well as four additional figures representing the infantry, cavalry, artillery, and navy. Most important were the twelve panels that would contain the names of every Rhode Islander who died in the war. The entire monument cost $50,000 dollars and was dedicated with much fanfare in Exchange Place (Kennedy Plaza) on September 16, 1871.

The first step in the monument process was the arduous task of carefully going through the records held by the adjutant general of Rhode Island and compiling a list of the names to be inscribed on the bronze panels. When he inherited the records in the early 1890s, Elisha Dyer Jr., himself a Civil War veteran and then the state’s Adjutant General, complained about the terrible condition of Rhode Island’s Civil War records. “The old and valuable records of the Rhode Island Regiments were being irreparably injured by the constant handling of those who were obliged to refer to them for information,” Dyer said. He added, “From the close of the war until June, 1883, the records were kept in paste-board boxes in an open bookcase in the Adjutant-General’s office, where they were easily accessible to the public, and, consequently, also in danger of being carried off and lost, as well as being spoiled or destroyed by careless handling.”

The committee only had a year to go through the thousands of muster rolls and compile a list of men from Rhode Island who had served in the regular service or in units from other states. Despite this momentous task, the committee completed its work and recorded the names of 1,771 Rhode Islanders who died of wounds, of disease while in service, in prisons, of accidents while in service, or of disease shortly after returning home from the army. These 1,771 names were inscribed upon the monument in Providence. Many names of the dead were, however, inadvertently missed.

Who arrived at the more accurate estimate? Was it Fox, widely regarded as the leading authority on Civil War statistics, or the state’s Adjutant General’s Office, which was officially responsible for recording the deaths of Rhode Island’s soldiers and sailors? The discrepancy between Fox’s figures and those of the state is 450. In other words, according to the state, Fox’s figure is off by a startling 25 per cent. When one deducts Rhode Islanders who served in the units of other states, as well as in the U.S. Army, U.S. Navy, and Marine Corps, the discrepancy is still 358 military deaths. In the opinion of this historian, the higher number arrived at by the State of Rhode Island in 1869—the very names that were inscribed on the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument—is more reliable than Fox’s calculation. But a deeper question remains: is the figure of 1,771 Rhode Islanders dying as a result of their Civil War service still understated?

I have long held the suspicion that the number of Rhode Islanders who died as a result of their Civil War service was over 2,000 and I regularly quote that number in my books and lectures on the Civil War. In 2014, I set out to test my hypothesis and finally determine the number of Rhode Islanders who died in the Civil War.

I began my study by focusing on the Seventh Rhode Island Volunteers, a regiment with which I as very familiar based on my great-great-great uncle Alfred Sheldon Knight’s service with that regiment. According to Fox, the Seventh sustained a loss of ninety officers and men killed in action and died of wounds, as well as 109 who “died of disease, accidents, in prison &c.” In his only other reference to the regiment, Fox stated that at the Battle of Fredericksburg the Seventh sustained casualties of 11 dead, 132 wounded and 15 missing, for a total of 158. Even with the limited resources of muster rolls and after-action reports that Fox was able to work with, I knew these figures were woefully low.

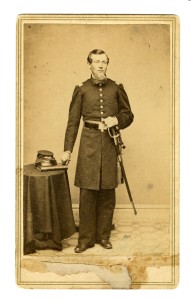

Alfred Sheldon Knight of Scituate, RI was a 29 year old dairy farmer who enlisted in Company C of the Seventh Rhode Island Volunteers in August 1862. He died of pneumonia on January 31, 1863 and is buried in the family cemetery on Scituate. He is listed as an official Civil War casualty from Rhode Island (Collection of Robert Grandchamp)

Based on a survey of records that have included entries in soldiers’ letters and diaries, cemetery records, pension files, town clerk death listings, and pretty much every scrap of paper that exists regarding the Seventh Rhode Island Volunteers, I determined that the regiment, which carried a total of 1,184 men on its rolls during the war, sustained a loss of 106 officers and men who died in combat or of wounds suffered in battle, as well as 110 who died of other causes. My total of 216 dead exceeds Fox’s estimate of 158 by 58.

Not included in my figures are the twenty-three men from the Seventh who died after being mustered out of the army, but whose deaths are directly attributable to their Civil War service. Among them is Lieutenant Colonel Job Arnold of Providence, who was discharged for disability in May 1864 after contracting malaria in Mississippi. Arnold died in Providence in December of 1869, and as reported in local papers, the cause of his death was a direct result of his service in the Seventh Rhode Island in the Deep South. Despite this link, Arnold’s name was never recorded on the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument in Providence either before or after its 1871 opening.

Lt. Col. Job Arnold of the Seventh Rhode Island, a resident of Providence is documented beyond a reasonable doubt to have died of illness contracted in the Civil War, five years after he was discharged (Collection of Robert Grandchamp)

In contrast to Fox’s claim of the Seventh’s losses at Fredericksburg, I determined that the regiment lost 3 officers and 46 men killed in action or mortally wounded, as well as 8 officers and 135 men who were wounded and 3 men who were captured, for a total of 195 casualties out of the roughly 570 men who went into the fight.

If the casualty figures can be so different for just one infantry regiment, I suspected that similar underreporting would be the case for the other regiments Rhode Island sent to the war. To begin my research, I drew up an adventurous plan to visit every town hall in Rhode Island, in addition to searching through historic cemeteries. I gave myself very limited parameters. The notation of death entered into the ledger by the clerk had to clearly indicate that the man died as a direct result of his Civil War service. In the occupation field, the man would have to be listed as a “soldier,” “volunteer” or “in U.S. Service.” Under the heading of death, the notation would have to indicate clearly that the man died of wounds or disease he suffered in the army. For example, in Cranston records, I encountered a recently discharged soldier who was run over by a railroad car shortly after returning home; this would not qualify as a Civil War death. In the graveyard search, the inscription on the headstone similarly would need to indicate unambiguously a Civil War death, such as the often encountered “Died of disease contracted in the service of his country” or “Died of wounds received in the Battle of….”

Although the Rhode Island General Assembly had required city and town clerks to record births, marriages, and deaths at the local level beginning in 1853, and had even sent books to the clerk offices for this purpose, by the 1860s, the system was still woefully inaccurate overall. Many such vital records continued to be recorded only in family Bibles. There were some exceptions: some clerks, such as those in Providence, Scituate, Coventry, and Warwick, maintained meticulous records, recording the deaths of men who were residents of the town, but died out of state while on military service, as well as those who died of wounds or disease at home. Indeed, the city clerk in Providence even took the time to record the street and address of where the deceased died. In addition, when a soldier died, the city clerk listed his unit. Surprisingly towns such as Burrillville, Glocester, Little Compton, and Westerly, who lost soldiers in the Civil War, and whose death records can be found elsewhere, recorded few soldiers’ deaths between 1861 and 1865 in their town vital records.

The quest to determine the number of Rhode Islanders who died in the Civil War, specifically those who came home and died of wounds or illness, took me to every clerk’s office in Rhode Island (except those in Narragansett, West Warwick, Central Falls, Woonsocket, North Smithfield, and Lincoln, townships that were not yet established at the time). I discovered that the clerk’s office in Central Falls contains the records for Smithfield, and North Providence’s Civil War era records are located at City Hall in Pawtucket. During the course of my research into these records, I recorded that the clerks had recorded over 500 soldiers in their records who died in the war, the vast majority of whom died at home of wounds or illness contracted in the service, and not in camp or on the battlefield. A good example is Samuel Towne of Battery C, First Rhode Island Light Artillery. He died in North Providence on February 13, 1863, of dysentery “contracted in Chickahominy,” which is located in Virginia.

It will take me months to wade through these records and to cross-check names against pension files, as well as those recorded in the Revised Register of Rhode Island Volunteers. While my research continues, here are several examples of what I have uncovered thus far.

Alpheus Salisbury. He was a married, thirty-year-old weaver from Scituate who served in Company K, Seventh Rhode Island Volunteers. Salisbury was shot in the neck in the Seventh’s assault up Marye’s Heights at the Battle of Fredericksburg. He was discharged from the service for disability on February 2, 1863 and sent home to Scituate. According to a published medical report filed by local doctor William H. Bowen, who treated Salisbury:

The most prominent symptoms were great pain in the head, frequent vomitings, constipation, and a kind of stupor. The wound in the head had not healed, and on probing it pus and blood were discharged. He learned that several pieces of bone had been taken away since the injury was inflicted. On July 1st, he saw the patient, in consultation with another physician. Pain in the head and vomiting still continued, and there was more perfect unconsciousness. The next morning there was paralysis of the side opposite the wound in the head, with one pupil contracted while the other was dilated, and he was perfectly comatose. He thinks that the wound was the primary and the original cause of death.

Private Salisbury died on July 2, 1863, as a direct result of his injuries sustained at Fredericksburg some seven months earlier; he was buried in Clayville Cemetery. Federal pension clerks agreed with Dr. Bowen’s findings and granted his wife a pension based on the fact that he died of his injuries sustained in military service. Despite the government’s findings, the name of Alpheus Salisbury is not recorded on the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument in Providence.

Some Rhode Island families lost two of their sons in the service of the Union; one Foster family lost three. Among those who lost two was the Pearce family of Richmond. William and Harvey Pearce enlisted in Battery B, First Rhode Island Light Artillery in March 1862. William quickly fell ill on the Virginia Peninsula and was discharged for disability on June 30, 1862. Harvey, meanwhile, struggled on until March 20, 1863, when he too was discharged for disability. Both men returned to Hopkinton where, according to inscriptions on their headstones, they “died of disease contracted in the U.S. Service during the Great Rebellion.” The two Pearce brothers were buried side-by-side at Wood River Cemetery in Hope Valley; the only indication they died in military service is the inscription upon their now fading headstones. Neither name is inscribed on the monument in Providence.

The Seventh Squadron of Rhode Island Cavalry is one of the state’s most interesting Civil War units. Composed of one company raised from college students from Dartmouth and Norwich, and one from men from northern Rhode Island, the squadron spent an uneventful three months of service in the Shenandoah Valley in the summer of 1862. Indeed, the regiment’s only glory came in the last days of their enlistment when they participated in a wild breakout from the Harpers Ferry garrison. According to the army records, only one squadron member died in the service—he was Arthur Coombs of Thetford, Vermont, a student from Norwich who succumbed from typhoid when the squadron was stationed near Winchester, Virginia. Another Seventh Squadron casualty, however, was Henry C. Colwell of Glocester. He died of typhoid on November 3, 1862, in Chepachet, a month after returning home from the front. While recorded in the town clerk’s records, Colwell’s name is not on the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument.

Ira E. Cole was seventeen and a farmer from Foster when he enlisted in Company E of the Third Rhode Island Heavy Artillery in the summer of 1861. Assigned to artillery duty in Georgia, Florida, and South Carolina, the Third, like the vast majority of Civil War regiments lost far more men to illness than to the enemy’s guns. While Private Cole survived his three-year enlistment without suffering any wounds, he returned to Foster in the summer of 1864 a sick man. On August 31, 1865, according to the town clerk’s notations, Cole died of “chronic dysentery contracted in camp” at his home in Foster. As with the majority of the men chronicled in my study, his name was not listed as a Civil War death by state authorities.

Perhaps the most interesting find so far in my search has been the discovery of Private Ira Cornell of Coventry, who served in Company K of the Seventh Rhode Island Volunteers. Cornell was a farmer who enlisted on August 14, 1862. A day later, his son Ira Cornell, Jr., also enlisted. The senior Cornell was wounded at Fredericksburg. But according to official army records, he “deserted at Cincinnati, O. April 1, 1863.” His son, Ira Cornell, Jr., was discharged for disability on October 14, 1864 and died in Coventry on April 29, 1867 of tuberculosis contracted in the army.

When I began to compile a roster of the Seventh Rhode Island, I listed the senior Cornell, in reliance on the official records, as having deserted. In the back of my mind, however, was the nagging thought of why a father would desert the army, leaving his teenage son alone in the service. One day last fall while researching in the Coventry Town Hall, whose town clerk had kept meticulous records of all soldiers from the town who died in the army, I discovered a shocking notation. While looking through the register of deaths in Coventry, I spotted the name of Ira Cornell. In the margin, the clerk had written the following: “Drowned in the Ohio River in the attempt of crossing it in the line of his duty.” This cause of death made sense to me, for on that date the steamer Kentucky transferred the Seventh Rhode Island across the Ohio River from Cincinnati, Ohio, to Covington, Kentucky. I found no reference in any letters from Seventh Rhode Island soldiers recording Cornell’s drowning, nor is it recorded in the official history of the regiment. Despite this, the Coventry records are highly accurate in other respects, and the clerk would have received first-hand information from a fellow soldier or a relative about the death. In addition, there is a grave marker in Pine Grove Cemetery in Coventry for Cornell that records the date of his death as April 1, 1863. In my record of the Seventh Rhode Island I have changed my entry to reflect that Ira Cornell died in the service of his country and did not desert the Union colors.

We will probably never know the exact number of Rhode Island soldiers who died as a result of battle injuries or of disease contracted in the service. For example, some men immediately left the state after mustering out and some never returned; tracking all of their death records is virtually impossible. In addition, as indicated in this article, many never had their deaths recorded in the vital records and today lie buried in unmarked graves.

It is my best estimate that, based on the available data, approximately 2,000 Rhode Island soldiers, sailors, and Marines died as a result of their Civil War service. My estimate, if accurate, would mean that the previous estimates were far too low. My work in this area will continue and I will refine my best estimate as appropriate.

Perhaps Thomas Williams Bicknell summed it up best in his massive The History of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations when describing the Civil War registers from the smallest state. “This report gives the name, date of enrollment, dates of mustering in and mustering out, promotions, transfers, of all soldiers and sailors from Rhode Island in the Civil War. Totals are not given and no record as to the nationality, birth, or birth-place of any of the whole number. In most cases the Rhode Island residence is noted. From these data it is almost impossible to determine how many men Rhode Island contributed to the War. It can safely be stated that the State furnished the full quota of men and supplies that she was called to render.”

(Banner image: Sgt. Samuel Rice of East Greenwich had joined the Kentish Guards of the Rhode Island Militia at age twelve. He died May 18, 1864 at the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House in Virginia (Collection of Robert Grandchamp))

For Additional Reading

The most important records I relied on were the birth, marriage, and death records at the city and town halls in Rhode Island, as well as the Papers of the Adjutant General contained at the Rhode Island State Archives in Providence. In addition, visits to cemeteries were important to this article, as Civil War soldiers’ headstones often contain excellent information about their service.

By far the single most important published work about Rhode Island and the Civil War is Elisha Dyer, Annual Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations for the Year 1865; Corrected, Revised, and Republished in Accordance with the Provisions of Chapters 705 and 767 of the Public Laws (Providence, RI: E.L. Freeman, 1893), in two volumes. This book is better known simply as the Revised Register of Rhode Island Volunteers.

On Civil War losses, see William F. Fox, Regimental Losses in the American Civil War: 1861-1865 (Albany, NY: Albany Publishing Company, 1889), and Harold R. Barker, History of the Rhode Island Combat Units in the Civil War: 1861-1865 (Providence, RI: privately printed, 1964).

On the Rhode Island Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument in Providence, see Report on the Committee on a Monument to the Rhode Island Soldiers’ and Sailors’ who perished in suppressing the Rebellion Made to the General Assembly, January Session, 1867 (Providence, RI: Providence Press, 1867) and Proceedings at the Dedication of the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument in Providence (Providence, RI: A. Crawford Greene, 1871).

For information on specific Rhode Island soldiers, please refer to the many published regimental histories on Rhode Island regiments and batteries. Most important for this study were Frederic Denison, Shot and Shell: The Third Rhode Island Heavy Artillery Regiment in the Rebellion, 1861-1865 (Providence, RI: J.A. & R.A. Reid, 1879) and William P. Hopkins, The Seventh Regiment Rhode Island Volunteers in the Civil War: 1862-1865 (Providence: Snow & Farnum, 1903).