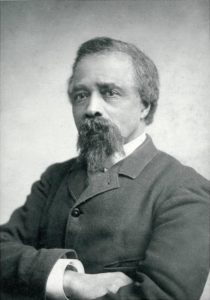

Edward Mitchell Bannister, one of Rhode Island’s foremost artists, was born in St. Andrews, New Brunswick, Canada in 1828. His father William came from Barbados in the West Indies; his mother, Hanna Alexander, was of Scottish ancestry. Edward’s interest in art was encouraged by his mother who raised Edward and his brother following her husband’s death in 1832.

Since Bannister’s artistic studies were limited, it is remarkable, indeed, that within five years after his arrival in Providence, one of Bannister’s paintings was accepted in the prestigious Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876. The painting, Under the Oaks, was selected for the first-prize bronze medal. Bannister related in considerable detail that the judges became indignant and originally wanted to “reconsider” the award upon discovering that Bannister was African American. The white competitors, however, upheld the decision and Bannister was awarded the bronze medal. The location of the painting has not been known since the turn of the century.

Edward worked briefly on coastal commercial ships before moving to Boston in 1848. There he worked as a barber and hairdresser in the African-American community. His desire to become an artist was thwarted by his inability to find an artist for a mentor or an art school who would accept him, so he became largely self-taught.

By the early 1850s, while he was working at a salon owned by Christiana Carteaux, he had acquired a local reputation for his portraits in crayon. In 1854, Bannister received his first commission for an oil painting–The Ship Outward Bound. In addition, his work relationship blossomed into a marital union when he married his boss in 1857. With her financial support, George was able to work full time as an artist by 1858 and opened a studio on Tremont Street. In the mid-1860s he spent time in New York City studying photography. He also attended evening drawing classes in Boston taught by physician and sculptor Dr. William Rimmer.

In 1869 or 1870 the Bannisters moved to Providence where Edward opened a studio and gained both recognition and acceptance because of the quality of his work.

Edward Mitchell Bannister, People Near Boat, 1893, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum. Scholars have suggested that the bearded man in this painting might be a self-portrait. Edward Bannister rarely included African American subjects in his paintings, focusing instead on pastoral landscape scenes, which brought him greater success in the art market. (See Holland, Edward Mitchell Bannister, 1992)

In 1876, at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, where industrial Rhode Island was much in evidence, Bannister became the first African-American artist to win a national award when he received a bronze medal for his large oil painting Under the Oaks. Bannister later recounted the story of how he was initially refused entrance to receive his prize because of his race. It is ironic that an accomplished Tonalist painter could be denied an award because of his own color!

Edward Mitchell Bannister, Sunset Scene, ca. 1875-1885, oil on wood, Smithsonian American Art Museum. Bannister lived by the sea for most of his life, and many of his paintings, including Sunset Scene, feature boats or bodies of water. Here, the glowing oranges and yellows immediately draw us into the center of the image, highlighting the indistinct trees and buildings in the background. Bannister’s intimate views of the American landscape contrast with the large vistas of mountains and canyons painted by many of his contemporaries. This picturesque scene, in which nature is shown as passive and calm, is typical of Bannister’s work.

Once back in Rhode Island, Bannister worked with the founders of the new Rhode Island School of Design, became a founder of the Providence Art Club, maintained a studio, and executed a variety of artworks. His style and predominantly pastoral subject matter were inspired by his admiration for Millet and the French Barbizon School.

Edward died of a heart attack on January 9, 1901 while attending services at the Elmwood Free Will Baptist Church in Providence, not far from his home at 60 Wilson Street, where he had recently moved. He was laid to rest in the North Burying Ground.

Five months after his death, the Providence Art Club held a memorial exhibit containing 101 of his paintings. At that event John Arnold wrote the following epitaph in the exhibit catalog:

His gentle disposition, his urbanity of manner and his generous appreciation of the work of others made him a welcome guest in all artistic circles . . . he was par excellence a landscape painter, the best our state has ever produced. He painted with profound feeling, not for pecuniary results, but to leave upon the canvas his impression of natural scenery, and to express his delight in the wondrous beauty of land, sea, and sky.

The art gallery at Rhode Island College is dedicated in his honor and Bannister House on Dodge Street in Providence, a senior living rehabilitation and health care center honors both Edward and his social activist wife Christiana. Today much of Edward’s work can be viewed at the Smithsonian American Art Museum and in Rhode Island at Brown University and the Rhode Island School of Design’s Museum of Art.

Edward Mitchell Bannister, Newsboy, 1869. In spite of his limited training and experience, Bannister was among Providence’s leading painters during the 1870s and 1880s. He was well liked and respected by his fellow citizens. On January 9, 1901, Bannister died while attending a prayer meeting at his church. Shortly after his death, the Providence Art Club mounted a memorial exhibition of 101 of Bannister’s paintings owned by Providence collectors. Bannister’s grave in North Burial Ground, Providence, is marked by a rough granite boulder ten feet high bearing a carving of a palette with the artist’s name and a pipe. A bronze plaque also adorns the monument and is inscribed with a poem, which reads in part, “This pure and lofty soul . . . who, while he portrayed nature, walked with God.”

Christiana Carteaux Bannister was born Christiana Babcock in North Kingstown sometime between 1820 and 1822. Her parents were John and Mary Babcock. Details concerning the exact date of her birth and background are obscure, but she appears to have been of mixed Native American and African-American parentage and was undoubtedly descended from slaves that worked the plantations of South County during the eighteenth century.

As a young woman she moved to Boston and took up the trade of hairdressing. During her twenty-five-year residence in Massachusetts she owned salons in both Boston and Worcester and prospered as an independent businesswoman and self-styled “hair doctress.”

Christiana first married Desiline Carteaux, a Boston clothes dealer, probably of Caribbean origin. After this union failed, she wed Canadian-born Edward Mitchell Bannister, who with her financial support, became one of America’s most successful black artists. The Bannisters lived and worked with Lewis Hayden, a noted black activist, in the operation of Boston’s Underground Railroad assisting runaway slaves to maintain their freedom. During the Civil War, Christiana helped to raise money to sustain the famous Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts Regiment of black soldiers, the unit immortalized in the 1999 motion picture Glory.

After the Civil War, the Bannisters moved to Providence where Christiana opened another salon and became a patron of the arts. She was deeply involved in improving the lives of African-American women and founded the Home for Aged and Colored Women at 45 East Transit Street, a facility that evolved into today’s Bannister Nursing Care Center on Dodge Street in Providence.

Christiana Bannister, by Edward Mitchell Bannister. She was an important social worker and activist in Rhode Island. Her bust is on the second floor of the State House. She was born Christiana Babcock circa 1820 in North Kingstown, Rhode Island to African American and Narragansett Indian parents. It is possible that her African-American grandparents lived and died as slaves.

Christiana Bannister’s significance is that she rose above the constraints that her era placed upon women and minorities and moved with facility and effectiveness among all levels of society from runaway slaves to Providence’s artistic community. She was a remarkable civic leader and humanitarian.

Christiana died on December 29, 1902 and was buried in her husband’s plot in the North Burying Ground. Ironically her name does not appear on the large gravestone erected in his honor, but a bronze bust of Christiana, based upon a portrait painted by her husband, was dedicated at the State House in December 2002.

[Banner Image: Edward Mitchell Bannister, Sunset Scene, ca. 1875-1885, oil on wood, Smithsonian American Art Museum]

[The above article is excerpted from Dr. Patrick T. Conley, The Leaders of Rhode Island’s Golden Age (History Press, 2019)] [Captions for the Edward Mitchell Bannister images are from the Smithsonian American Art Museum website]