On May 27, 1791, Thomas Mount, a white man born in New Jersey, was hanged in Little Rest (now Kingston). Hanging was never particularly common in Rhode Island. What makes Mount’s hanging extraordinary was the crime that led to his death sentence: burglary. The crime of burglary does not seem particularly egregious in the modern world, and even then many questioned whether it was a hanging offense. While burglary was a hanging offense under Rhode Island statutes, it was rarely applied by the courts. Rhode Island’s list of capital crimes included arson, rape, robbery, burglary, as well as murder, but few were hanged for such crimes other than murder. Mount’s death caused Rhode Islanders to question this harsh punishment in the case of the relatively petty crimes of burglary and robbery.

The 27-year old Mount was caught stealing from Joseph Potter’s store in Hopkinton, Rhode Island, and was tied to earlier thefts in Newport. He was sent to the Newport jail, probably because at the time the Washington County jail in Little Rest was in poor condition and was easy to break out of, and Mount was a known jail. breaker. While confined in jail, and after his conviction at trial and death sentence, Mount decided to write his “confession.” He admitted to numerous acts of theft. Perhaps Mount wrote the remarkable document in the hope that his honest account and repentance would win sympathetic support and perhaps a reprieve from the death sentence by the state governor or General Assembly. Or perhaps Mount simply felt a need to unburden himself before he met his fate. These types of confessions by condemned men were not unknown in early America (and before that, in Great Britain).

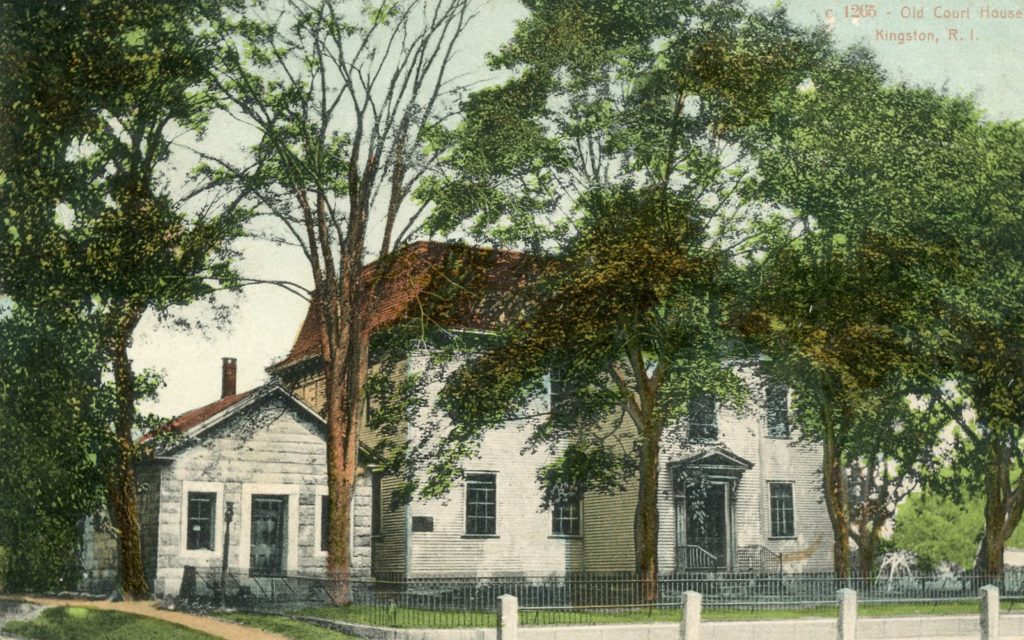

Thomas Mount apparently made an appearance at the Washington County Court House in Little Rest in 1791, but he was tried at Newport. By the time this postcard image was made, a stone archives and mansard roof were added to the Court House (Sanford Neuschatz Collection)

According to Thomas Mount, he was born in 1764 in New Jersey, the son of unmarried parents. He began a life of crime when he moved to New York by playing truant and “upon Sundays especially was fond of doing mischief such as robbing orchards and spreading my wicked example among all the boys I could get acquainted with.” In the Revolutionary War, seeking enlistment bounties, he joined the Continental Army, later deserted to join the British ranks, and then returned to patriot ranks. Tiring of the army, Mount left for the sea where he led a life of securing advance pay and “jumping” ships. For the next twelve years, back on land, he engaged in various thefts, robberies, and house and jail breakings throughout the states.

Mount broke jail more than a dozen times. He was set in the stocks, pilloried, and made to sit upon more than one gallows with a noose around his neck. He bore the scars of many legally-imposed lashes on his back. For one act of theft, he was given 100 lashes and 25 more for “giving the court saucy answers.”

Mount and his wife, Catherine, arrived in Newport where he engaged in further thefts. When Mount came to Hopkinton, he was caught stealing. Here is Mount’s own account of the Hopkinton affair from his “confession.”

“Next night Stanton, Williams, and I set off to break into Joseph Potter’s store; I broke open a mill and took a crowbar out of it, and we all three went in, I first, and they following, I being most forward in this business. I lighted a candle and handed down the goods, about several hundred dollars’ worth, and some money, two or three dollars, and carried them to Stanton’s house, where .we divided them into three parts and cast lots. Williams and I took our shares. After giving Stanton out of my share 8 or 9 pounds worth of goods for a mare, and hiding the goods under two corn stalks and under a barn about five miles from Stanton’s house, we set off for Voluntown, there were apprehended and brought back to Hopkinton, where Stanton, I and my wife were tried for breaking open the mill; Stanton’s wife and Williams were admitted as State’s evidence. Accordingly, I was sentenced to receive 20 lashes and my wife 10 (although she was innocent). Paid the fine by giving up part of my clothes, then committed to Newport gaol, tried for breaking Potter’s shop, found guilty, and received the sentence of death.

—And the Lord have mercy upon me.”

The trial of the accused was held in Newport in 1791. One of his attorneys was Little Rest’s Elisha Reynolds Potter, Sr., soon to become a prominent state-wide politician. Potter apparently assisted Mount on humanitarian grounds. Potter’s efforts were to no avail, as the jury convicted him.

The death penalty was rarely imposed by Rhode Island judges for the crime of burglary. An unfortunate man, John Shearman, had been convicted of burglary and hanged in Newport in 1764, but he had been the last. Late one night in October 1761, at Newport, Shearman broke into the house of a female shopkeeper named Sarah Kumroil and stole substantial amounts of paper money and coins, as well as a tortoise-shell snuffbox set with silver and pearls, and a pair of gold cufflinks. Tried at Newport, Shearman was sentenced to death. The Rhode Island General Assembly agreed to postpone the hanging until Shearman’s appeal could be considered back in London (Rhode Island was still a British colony). But when the impatient Shearman got tired of waiting and broke out of jail, and was caught, an angry General Assembly revoked Shearman’s reprieve. Shearman was hanged in Newport on November 16, 1764. But that was 26 years ago, before the American Revolution.

Shockingly, the three judge panel sentenced Mount to “be hanged by the neck till he be dead.” They were likely influenced by the high value of goods stolen—“several hundred dollars’ worth” according to Mount. Such a loss may have resulted in the bankruptcy of the storeowner, Joseph Potter. In those days, bankruptcy was even more serious a matter than today. A bankrupt would be sent to jail until all debts were paid (often by friends and family). Mount’s accomplice, Joseph Stanton, also received a death sentence.

Both Mount and Stanton filed petitions for pardons with the General Assembly. Stanton’s petition was granted, but Mount’s was not. The General Assembly must have been influenced by Mount’s extensive criminal record. Perhaps the General Assembly felt that Mount was beyond redemption, which Mount himself admitted, and applied an early and harsh form of the “three strikes and you are out” rule.

In the trial, Mount also failed to show remorse, which did not help his cause. The fact that he was only a recent arrival in Rhode Island also likely played a role. The General Assembly may have wanted to send a message to criminals outside the state not to enter Rhode Island to commit crimes.

Mount was ordered back to the Newport jail, where he tried two jail breaks. One attempt failed due to Mount’s “unaccountable absence of mind,” as the condemned man described it. Mount lamented, “I have broken every Prison in which I hitherto have been confined—but defeated twice—in this I see the Hand of God.”

Four days before his execution, Washington County deputy sheriff Robert Sands transported Mount and his wife Catherine to the Little Rest jail (Sands, from Little Rest, also helped to capture Mount). Washington County Sheriff Beriah Brown and jailer William Wilson Pollack took no chances. They hired about a dozen men to guard against a last-minute escape by Mount. Elisha Potter, to his credit, spent Mount’s last night with Mount to hearten his spirits.

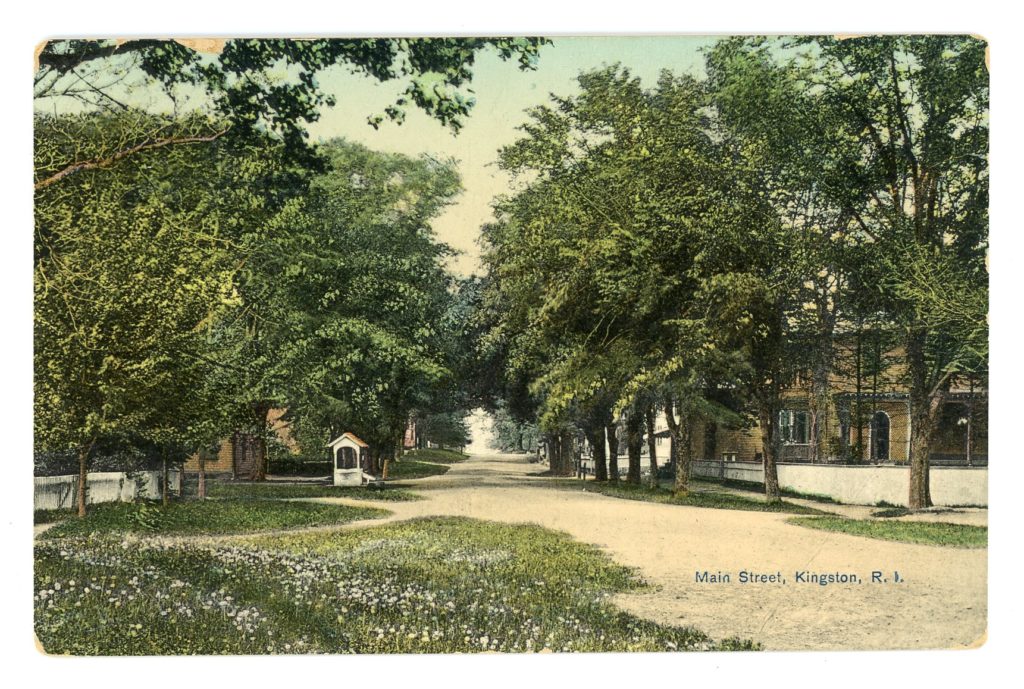

The bucolic village of Little Rest, now Kingston, was the scene of Thomas Mount’s hanging in 1791 (Sanford Neuschatz Collection)

Many people thought that execution was too harsh a penalty for burglary. This feeling seems quite evident from the following account in the United States Chronicle, a Providence newspaper, dated June 16, 1791.

“Passing over many Things relative to his Behavior while in prison at Little Rest, and during the Interval of his leaving the Prison, and going to the Place of Execution, suffice it to be remarked, that firm to the last, his Mind averted from Sublimely Things and steadfastly fixed on God and ascending up to Heaven in Holy Ecstasy of Prayer he declared his “willingness to be offered up a Sacrifice to divine & human Justice—he forgave all men in Hopes of finding Forgiveness with God”—and after he was turned off—he was distinctly heard to breath his last in prayer ‘Lord have mercy on me—Lord’—here he was suffocated.”

“Multitudes mourned and bewailed him—No triumph over his melancholy end disgraced the feelings of humanity—for the space of a quarter of an hour nothing was to be heard but prayers mixed with sighs and groans. Every face displayed the signs of being affected with the solemnities of his death and most tender sympathies of woe trickled down almost every cheek.”

The place of execution reportedly was about one-quarter mile below the Court House down Little Rest Hill (probably where the parking lot for the University of Rhode Island now sits opposite the athletic fields). Reportedly, Mount was buried close by and his grave was visible as late as 1869, but his gravesite now is unknown.

Here is a poignant poem written by Thomas Mount in his “confession”:

Thomas Mount it is my name

And to my shame cannot deny;

In New Jersey I was born,

And on Little Rest now must die.

Mount’s execution apparently caused some judges and the General Assembly (which could and did grant pardons) to be more reluctant to impose the death penalty in cases of burglary and other property crimes. From 1798 to 1833, there were no executions by the state of Rhode Island other than two for murder, although there were many instances of criminals convicted of burglary. In 1834, Charles Brown, a black man, was convicted of highway robbery in Providence. His sentence of hanging was not commuted, probably because he struck the victim with a heavy club. But that is another sad story.

The Westerly Historical Society holds a small keg of rum that is claimed to have been one of the items stolen by Thomas Mount from Joseph Potter’s store. The following inscription has been attached to it probably since the early 1900s. The accuracy of the claims cannot be proved by the author, in part because Mount’s court record could not be located in the Rhode Island Judicial Center, at least for the time being. From Mount’s own words, we do know that he stole much more than a single runlet of rum.

“For stealing this runlet, filled with rum, that last man hanged for theft in this county, received his sentence.”

“The runlet was the property of the Potters of Potter Hill, and was taken at night from their store that was attached to their dwelling. The lawyer defending the culprit maintained that since the runlet was taken from a store, his client could not receive more than imprisonment. The lawyer for the state maintained that the runlet was stolen from a dwelling in the night time, and that hence the punishment must be death, as the law then stood.”

“The judge determined that this point could be settled only by determining whether the store and house were one building, and to settle this, shingles were torn off and it was found that the beams were mortised into those of the house. So the man was hanged.”

This runlet of rum was said to have been one of the items stolen by Thomas Mount from Joseph Potter’s store (Westerly Historical Society Collections)

Mount’s execution apparently caused some judges and the General Assembly (which could and did grant pardons) to be more reluctant to impose the death penalty in cases of burglary and other property crimes. From 1798 to 1833, there were no executions by the state of Rhode Island other than two for murder, although there were many instances of criminals convicted of burglary. In 1834, Charles Brown, a black man, was convicted of highway robbery in Providence. His sentence of hanging was not commuted, probably because he struck the victim with a heavy club. But that is another sad story.

[Banner image: The bucolic village of Little Rest, now Kingston, was the scene of Thomas Mount’s hanging in 1791 (Sanford Neuschatz Collection)]

Sources:

For Thomas Mount, see Miller, William Davis, “Thomas Mount,” Rhode Island Historical Society Collections 53-58 (April 1927); Bickford, Christopher, Crime, Punishment, and the Washington County Jail (Pettaquamscutt Historical Society, 2002), 42-43; Wells, J. Hagadom, “Kingston Annals,” transcript in South County History Center, 48 (location of hanging). Cole refers to a “Hanging Lot” where Mount was hung. Cole, J. R., History of Washington and Kent Counties (W.W. Preston, 1889), 483. For fees paid to Robert Sands of Little Rest, as deputy sheriff of Washington County, apparently for capturing and guarding Thomas Mount, see Rhode Island Acts & Resolves, Feb. 1791 Session, v. I, 20-21 (“for apprehending and committing divers Persons charged with high Crimes and Misdemeanors”); Rhode Island Acts & Resolves, May 1791 Session, v. I, 27 (audit of accounts of Sands and another man who helped bring Mount from Newport). The author thanks Ed Fazio for bringing to his attention the runlet of rum held by the Westerly Historical Society said to have been stolen by Thomas Mount and the photograph of it.

For John Shearman and Charles Brown, see Daniel Allen Hearn, Legal Executions in New England, A Comprehensive Reference, 1623-1960 (McFarland, 1999), 146 and 219.