[The following is perhaps the earliest official report on slavery in Rhode Island and the colony’s ties to the African slave trade. Historians and students of history of Rhode Island have wondered where the first Black enslaved people came from who arrived in colonial Rhode Island. The following report from Governor Samuel Cranston provides some answers. It also indicates that by 1708, Rhode Island had only one slave ship arrive in the colony from Africa (at least according to official custom house records), and this voyage did not have Rhode Island investors or a Rhode Island captain. In later years, after 1725, there would be many slave voyages financed by Newport merchants and slave ships commanded by Newport captains.]

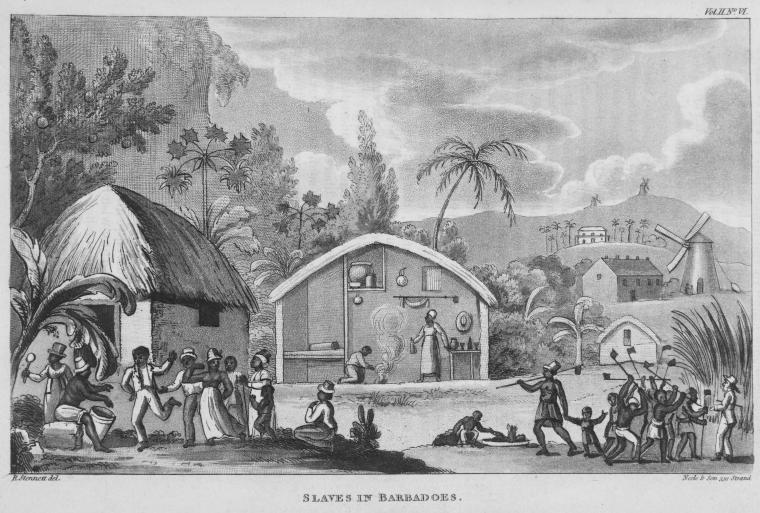

The drawing shows Quakers in the island of Barbados with enslaved people behind them. Barbados was the first British colonial possession to rely heavily on enslaved labor (New York Public Library Digital Collections)

Report from Governor Samuel Cranston of Rhode Island to the Board of Trade in London, writing from Newport on December 5, 1708:[1]

May it please your Lordships: In obedience to your Lordships’ commands of the 15th of April last, to the trade of Africa.

We, having inspected into the books of Her Majesty’s custom, and informed ourselves from the proper officers thereof, by strict inquiry, can lay before your Lordships no other account of that trade [other] than the following viz.:

- That from the 24th of June, 1698, to the 25th of December, 1707, we have not had any negroes imported into this colony from the coast of Africa, neither on the account of the Royal African Company, or by any of the separate traders.

- That on the 30th day of May, 1696, arrived at this port from the coast of Africa, the brigantine Seaflower, Thomas Windsor, master, having on board her forty-seven negroes, fourteen of which he disposed of in this colony, for betwixt £30 and £35 per head; the rest he transported by land for Boston, where his owners lived.

- That on the 10th of August, the 19th and 28th of October, in the year 1700, sailed from this port three vessels, directly for the coast of Africa; the two former were sloops, the one commanded by Nichos Hillgrove, the other by Jacob Bill: the last ship, commanded by Edwin Carter, who was part owner of the said three vessels, in company with Thomas Bruster, and John Bates, merchants of Barbados, and separate traders from thence to the coast of Africa; the said three vessels arriving safe to Barbados from the coast of Africa, where they made the disposition of their negroes.

- That we have never had any vessels from the coast of Africa to this colony, nor any trade there, the brigantine above mentioned excepted.

- That the whole and only supply of negroes to this colony, is from the island of Barbados; from whence is imported one year with another, betwixt twenty and thirty, and if those arrive well and sound, the general price is from £30 to £40 per head.

According to your Lordships’ desire, we have advised with the chiefest of our planters, and find but small encouragement for that trade to this colony; since by the best computation we can make, there would not be disposed in this colony above twenty or thirty at the most, annually; the reasons of which are chiefly to be attributed to the general dislike our planters have for them, by reason of their turbulent and unruly tempers.

And that most of our planters that are able and willing to purchase any of them, are supplied by the offspring of those they have already, which increase daily; and that the inclination of our people in general, is to employ white servants before negroes.

Thus we have given your Lordships a true and faithful account of what hath occurred, relating to the trade of Africa from this colony; and if, for the future, our trade should be extended to those parts, we shall not fail transmitting accounts thereof according to your Lordships’ orders.

Image shows an idealized visions of slavery in Barbados; in fact, conditions for enslaved people there were harsh and deadly (New York Public Library Digital Collections)

For purposes of this article, the key parts of Cranston’s letter are as follows: “That the whole and only supply of negroes to this colony, is from the island of Barbados; from whence is imported one year with another, betwixt twenty and thirty” and that the voyage of the Seaflower in 1696 was the only slave ship that directly landed in Rhode Island from Africa prior to 1709. Cranston also adds that the investors of the voyage for the Seaflower hailed from Boston. (Captain Thomas Windsor of the Seaflower commanded another slave ship that arrived in Boston in 1700—this time not even stopping first at Newport).[2]

Accordingly, I agree that the first imports of enslaved people into Rhode Island were likely largely the result of purchases by Newport merchants of Black enslaved people from Barbados merchants. These shipments would have been part of the intra-American slave trade. British slave ship captains would have carried the African captives to Barbados, as part of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, and then Rhode Island merchants would have purchased some from Barbados merchants. Starting from the mid-seventeenth century, Newport had an active “carrying” trade with the British-controlled island of Barbados—taking foodstuffs and other New England products to the island.[3] At this time, as stated in Cranston’s letter, there were no known slave ship voyages sailing out of Newport or other Rhode Island ports.

There is a surviving record of at least one purchase by a Rhode Islander of an enslaved person from a Barbados merchant. On June 7, 1695, William Hawkins of Providence purchased “the said Negro man Jack forever” from William Mackcollin, a Barbados merchant. In 1705, Hawkins agreed to manumit Jack (“having a respect for him”)—but only after Jack performed continuing services for another twenty years, until June 27, 1725. At the time of his 1695 purchase, Jack was about twenty years old. So, he would have been manumitted, if he lived that long and if the promise were kept, when he was about fifty years old.[4]

The situation with Rhode Island merchants was likely similar to that of the Pepperell merchant family from Massachusetts. Rhode Island historian William B. Weeden wrote in an article on New England slavery in 1887:

The Pepperells did not import negroes directly from Africa; their vessels brought them frequently from the West Indies. Indeed, it was said that “almost every vessel in the West India trade would return with a few.” The West Indies being the largest market, naturally controlled the destination of the cargoes [of African captives], even when the vessels went from New England, as we have seen in one instance from Newport.[5]

By “West Indies” here, Weeden means mostly Barbados, which was the main sugar producing plantation colony held by the British at this time. Rhode Islanders may also have purchased some enslaved people from merchants in Boston and New York City, where a total of eleven slave ships dropped off African captives from 1678 to 1705.[6]

The first slave ship from Africa that put into a Rhode Island port may have been the Elizabeth, partly owned by prominent Boston merchant John Saffin, in 1681. Governor Cranston may not have known about this one because it evaded being recorded in official records. The slave ship initially landed in Swansea, Massachusetts, but Saffin then ordered it to sail to Rhode Island to engage in “business” and then sail to Boston.[7] Whether there were any sales in Rhode Island is not known, but there probably were. It could have been that Saffin’s group had contracted with buyers from Rhode Island or some of the investors hailed from Rhode Island and demanded that they receive their shares of the African captives.

Even when those slave ship voyages from Rhode Island increased markedly after 1725, most all of the destinations of the slave ships were British-controlled Caribbean islands, such as Jamaica, Barbados, and Antigua, and sometimes Virginia or Maryland (and later, South Carolina). Even at the height of Rhode Island’s slave trade in colonial times, only on rare occasions did a slave ship sail directly from Africa to Rhode Island, resulting in slave auctions held in the colony (I will have an article on such auctions in a future article).

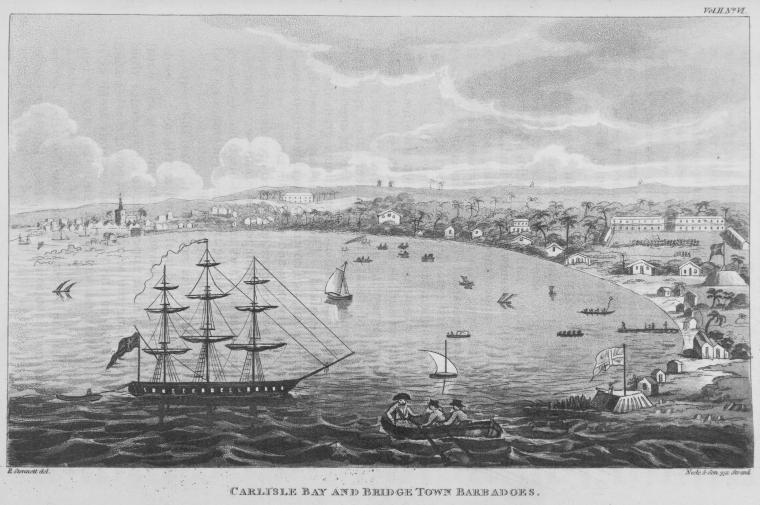

Bridgetown Harbor, the largest port on the island of Barbados. Rhode Island merchants would have purchased enslaved people here and carried them back to Rhode Island in the seventeenth century and early part of the eighteenth century (New York Public Library Digital Collections)

Another important statement in Cranston’s letter is that “most of our planters that are able and willing to purchase any of them [enslaved Black people], are supplied by the offspring of those they have already, which increase daily.” In other words, the large farmers (called planters) in colonial Rhode Island mostly relied on the natural increase in the enslaved population—that is, the excess of births exceeding deaths. By comparison, in British-controlled Caribbean islands in colonial times, the working conditions and treatment of the enslaved were so horrible that natural and unnatural deaths of enslaved people far exceeded the increase by the natural birth rate.[8]

The Royal African Company of slave merchants in Great Britain, centered in Bristol, Liverpool, and London, was formed in 1672 to obtain a monopoly on the British slave trade. But since its members were failing to send sufficient slave ships to meet the strong demand for African captives, especially in the British-controlled Caribbean islands, private merchants who were not part of the company were increasingly willing to skirt the laws and fit out their own slave ship voyages. In an effort to increase the African slave trade, the Board of Trade in London requested this report from Governor Cranston to determine the number of captives carried by the Royal African Company and those carried by private traders.

Captain Windsor’s voyage on the Seaflower in 1696 violated the Royal African Company’s monopoly. The first slave trading voyages departing Rhode Island were three from Newport in 1700; each of them was financed largely by Barbados merchants and landed most of their African captives in Barbados.[9] The great slave trade historian Elizabeth Donnan notes that while the British liberalized their slave trade rules in 1698, these three voyages still likely violated the Royal African Company’s monopoly.[10]

Donnan put colonial Rhode Island mercantile developments in context:

Cranston accompanied this report by two others dealing with subjects about which the Board of Trade had asked information. A comparison of these reports with that sent to the Board by Governor Peleg Sanford in 1680 shows that during the intervening quarter of a century, Rhode Island had passed from a planting to a trading community. Sanford reported that there were no merchants nor men of considerable estates, no shipping save a few sloops, and no customs duties. The Newport customhouse was established in 1681; a duty on molasse was laid in 1696. During the 1680s, Rhode Island developed the great skill in distilling, which was to play so large a part in her later commercial history. Cranston’s account pictures a commercial society in close intercourse with the West Indies (Caribbean islands) and ripe for wider trading ventures. Shipbuilding had already come to be one of the important activities of the colony during the preceding decade.[11]

In 1708, the first census of colonial Rhode Island that accounted for Black people was taken. Governor Cranston also sent the Board the census results. The total population was 7,181, of which 426 were Blacks. White servants were also counted—these were white people bound for a term of years to work for a farmer, tradesman, or merchant. The “Black servants” at this time were almost all enslaved. Here is the breakdown:

Town, Total Population; “Black servants;” “White servants” in Rhode Island in 1708

Newport, 2,203; 220; 20

Providence, 1,446; 7; 6

Portsmouth, 628; 40; 8

Warwick, 480; 10; 4

New Shoreham [Block Island], 208; 6; 0

Kingstown, 1,200; 85; 0

Jamestown, 206; 32; 9

Greenwich, 240; 6; 3

Total, 7,181; 426; 56

From: Samuel Cranston, Governor of Rhode Island, Newport, December 5, 1708[12]

(At this time, Kingstown included all of current South County; Greenwich included East and West Greenwich; Newport included Middletown; and Providence included the port of Providence and most of northern Rhode Island).

I suspect the numbers for Kingstown are estimates, given the round numbers and number 0 for white servants. I would have thought that at the time, there would have been at last ten white servants and probably more.

Cranston’s statement in his 1708 report that Rhode Island’s planters preferred white servants over enslaved labor is dubious, given that the enslaved Black population far outstripped the number of white servants.

Perhaps the most shocking statement in Cranston’s letter is in the second paragraph, quoted again here:

That on the 30th day of May, 1696, arrived at this port from the coast of Africa, the brigantine Seaflower, Thomas Windsor, master, having on board her forty-seven negroes, fourteen of which he disposed of in this colony, for betwixt £30 and £35 per head; the rest he transported by land for Boston, where his owners lived.

This statement means that Windsor held an auction for the 47 African captives, probably at a wharf in Newport, at which fourteen were sold. Cranston’s information also means that a group of 33 enslaved Africans, some of whom would have been confined in shackles, were forced to march on public roads in Rhode Island on the overland trip to Boston.

A permission slip for a Barbados merchant ship to enter Newport Harbor, signed by Rhode Island Governor William Greene, November 17, 1759 (New York Public Library Digital Collections)

Notes

[1] Printed in John R. Bartlett, ed., Records of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, vol. 4 (Providence: Knowles, Anthony & Co., 1859), 54-55. [2] See the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database at tps://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database (voyage #25154). [3] See Carl Bridenbaugh, Fat Mutton and Liberty of Conscience, Society in Rhode Island, 1636-1690 (Providence: Brown University Press, 1974), 116-24. [4] William Hawkins manumission, October 24, 1705, in The Early Records of the Town of Providence, vol. IV (Providence: Snow & Farnham, 1893), 71-72. [5] Quoted in William B. Weeden, “The Early African Slave Trade in New England,” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, New Series, 5 (1887), 114. [6] See the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database at tps://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database. By limiting the search of slave trade voyages to those occurring from 1660 to 1709 and with a principal landing place of what would become the United States, the following is shown, in addition to the Seaflower voyage: 2 slave trade voyages with captives landed in Boston (1678 and 1700) and 8 slave trade voyages with captives landed in New York City (1694, 1697 (two), 1698 (four), and 1705). [7] See Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database at tps://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database (voyage #25153); John Saffin and Others to William Welstead, June 12, 1681, in Elizabeth Donnan, Documents Illustrative of the History of the Slave Trade to America, vol. III (Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1932), 15-16. [8] See Christian McBurney, Dark Voyage: An American Privateer’s War on Britain’s African Slave Trade (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2022), 5-8. [9] See the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database at tps://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database. By limiting the search of slave trade voyages to those occurring from 1660 to 1709 and with a departure from Mainland North America, the following is shown: the Mary, British flag vessel, #15164; Thomas and John, British flag vessel, #20211; Edwin and Joseph, #15163. See also Donnan, Documents Illustrative of the Slave Trade, 27 and 29; Weeden, “The Early African Slave Trade in New England,” 112. [10] See Donnan, Documents Illustrative of the Slave Trade, 110, n. 2. [11] Ibid., 109, item 83, n. 2. [12] Rhode Island 1708 Census, in Bartlett, ed., Records of Rhode Island, vol. 4, 59.