The Sprague Brothers’ Union (Horse) Railroad decided to hire the best available personnel by paying generous wages. Horsecar workers received a two-dollar-a-day salary at the inception of service in 1864. By the 1880s drivers earned $2.25 and conductors $2.50. Extra remuneration for the conductor probably reflected an attitude that a well-compensated fare collector would be less likely to steal. An 1877 article in the Providence Journal commented that “there are always plenty of applications for places on the cars, but the men who hold the places do not often resign.” Fourteen years later another article in the same newspaper reported a similar phenomenon: “A large number of horsecar conductors and drivers cling to the brakes and punches for many years.” More than a third of the work force of three hundred had a dozen years’ seniority by then, “a very contented class of men.”

Employees did have one universal complaint: the number of hours on the road. John Benchley, who operated the first Union Railroad horsecar in 1865, remembered: “We worked from early morning until late at night without, any regard to time.” Later in his career he ran a route from 11:42 A.M. until midnight with only short breaks at the end of each trip. Another horsecar veteran claimed that “working days were measured by the rise and set of the sun rather than any prescribed hours of labor.” By the 1880s a day’s labor had been whittled to twelve hours but with a wrinkle. In the railway industry, as in mass transit today, passenger traffic determined the frequency of trips and service. The company needed more employees and cars for rush hour than off-peak hours of the day. Drivers and conductors often had to serve split shifts. There could be five breaks during the day ranging from thirty minutes to several hours each. A work schedule could stretch eighteen hours with no extra compensation for intervening time. On busy holidays drivers arid conductors toiled for as long as sixteen hours without relief.

The long days took a toll. “It wasn’t anything unusual, for a horse car driver when he got at the end of the line, to sit down for a snooze,” confessed an old timer hired in 1889, “and sometimes it was necessary to send out to see why he wasn’t showing up, only to find his snooze had developed into a protracted sleep.” Drivers that ran late-night cars often tied the reins to the dasher on the return trip to the car barn. They joined the conductor inside the horsecar for a nap. Horses usually stopped at the barn through habit. One evening, however, a team kept going another mile before stopping. The crew slept through the extracurricular ride until two in the morning. The driver awkwardly pulled in several hours’ late. Despite the grueling schedule and the occasional sleepiness, drivers and conductors seldom missed work or appeared late. Howard Lawton spent forty-four years on the cars without ever being tardy. Ben Jepson, a veteran driver and motorman on Broad Street, logged fifty-two years for the Union Railroad with only one “miss” when “his faithful alarm clock went back on him.”

Driver and conductor pose in front of red and green Cranston Street horsecar #92 in front of the stable and car house. The location of the photo is Cranston Street and Webster Avenue (Collection of Loris J. Bass)]

“Those were the good old days,” claimed Thomas Thompson about the horsecar era, “when a fellow WORKED from 4:30 in the morning until 5:30 in the afternoon, THIRTEEN hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year.” There were no scheduled days off in that period. No paid vacations. Employees got time off by arranging for a “spare man” to relieve them for a few hours or a few days. Aspiring drivers and conductors usually served a type of informal apprenticeship before assuming full-time duties. They worked the “list” or “slate.” Vacations by transit workers were always a subject of local newspaper stories. One account noted a Mount Pleasant conductor who visited friends in Fall River, Massachusetts, for a day; another announced that several employees went fishing; a third trumpeted the news that a conductor took a two-week vacation, a very unusual affair.

The jobs of drivers and conductors were quite different. “The conductor, according to a newspaper article about the Union Railroad in 1877, “is expected to see everybody within the car who may want to get out, and everybody without who, may want to get in, each on the first indication of their wish. A conductor controlled the car’s bells, which signaled the driver when to stop and start. “The conductor will be held strictly accountable for any damage to the car, caused by his neglect or carelessness.” Nor could the conductor ever sit down while on duty; the Union Railroad suspended six for this infraction in 1885. The company rule book stipulated that the conductor had to “keep his car clean and in good order, and dust the seats and clean the windows and lamps every morning before starting.”

This picture captures the driver at the front, and the conductor in the rear, but not the horse. The photographer did capture the handsome waiting room on Elmwood Avenue next to Roger Williams Park ((Scott Molloy Collection, Robert L. Carothers Library (at URI), Special Collections and University Archives)

The conductor collected fares first and foremost, but diplomatically. “He must take every fare, but must never, twice ask the same person to pay. If he takes counterfeit money it is his loss; if he gives too much change, he alone must bear it. At the end of each trip he had to count “the number of cash fares, tickets, children’s fares, letter carriers, police, complimentary, official and employee fares.” In 1865 conductors carried two dollars’ worth of change and by 1889 nineteen dollars and a dollar’s worth of tickets in an old tin box hitched to the front dasher. Adult fares were six cents, and children paid half that. In 1872 the Union Railroad supplied each conductor with a bell punch that registered fares. “These were used to punch out small disks from a green strip. On the punch was a bowl-like receptacle into which these small pieces fell. It was by counting these pieces in the office that a record was obtained of the riding. The conductor had to make good on any shortages.”

“There was,” according to the Providence Journal, “great indignation among the conductors when the bell punch appeared.” Fare collectors felt the machine impugned their integrity. Mark Twain popularized the conductors’ protest:

Conductor, When you receive a fare, Punch in the presence of the passenjare! A blue trip slip for an eight-cent fare,

A buff trip slip for a six-cent fare,

A pink trip slip for a three-cent fare, Punch in the presence of the passenjare!

Chorus

Punch brothers! punch with care!

Punch in the presence of the passenjare!

Several conductors resigned in protest against, the criminal implications symbolized by the bell punch. Although the Union Railroad admitted it had no evidence of organized pilferage, other railway companies had uncovered fraud. Passengers also resented the implications of the bell punch as a “badge of disgrace.” Patrons often encouraged conductors to pocket fares as a protest against the system. In either case, liberal wages gave pause to employees with larcenous thoughts, but severely crowded horsecars facilitated stealing.

Drivers entertained different types of problems. They had to be men “of considerable physical strength, and a man in whom a phrenologist would find form large.” Drivers also had to be attentive to the road and ambidextrous enough “to drive three or four horses with one hand and work the brake with the other without even the slightest confusion between the two.” Weather caused the greatest problems for drivers. Open-fronted cars exposed them to the weather’s teeth. John Wall described a driver’s uniform in 1886: “In cold weather we usually wore an overcoat down to our feet, under this one or two sweaters, and a short coat, a pair of felt top boots, over these a pair of overshoes, a scotch cap well down over our ears (nothing visible except our noses), and one or two pair of mittens, with the temperature down below zero, the rain and sleet beating in on us with no protection whatsoever.”

A driver turned meteorologist explained the frigid winter of 1885-86 as “the result of trying to blow the north down this way so as to save going in sear.ch of it.” The local press expressed great sympathy for the occupational hazards of driving a car in such conditions. In December 1872 “blinding sheets of snow rendered the occupation of the drivers anything but agreeable.” Legendary blizzards imprisoned drivers and conductors in horsecars for several days at a time until the plows broke through. During the Great Blizzard of 1888 horsecars traveled Elmwood Avenue off the tracks, “just bumping along as best they could. People didn’t mind rough riding in those days, the extra bumping kept them from freezing to death in the cars, so they really liked it.” The company cut wages by paying carmen only for the number of trips, completed regardless of hours spent on the road in these conditions.

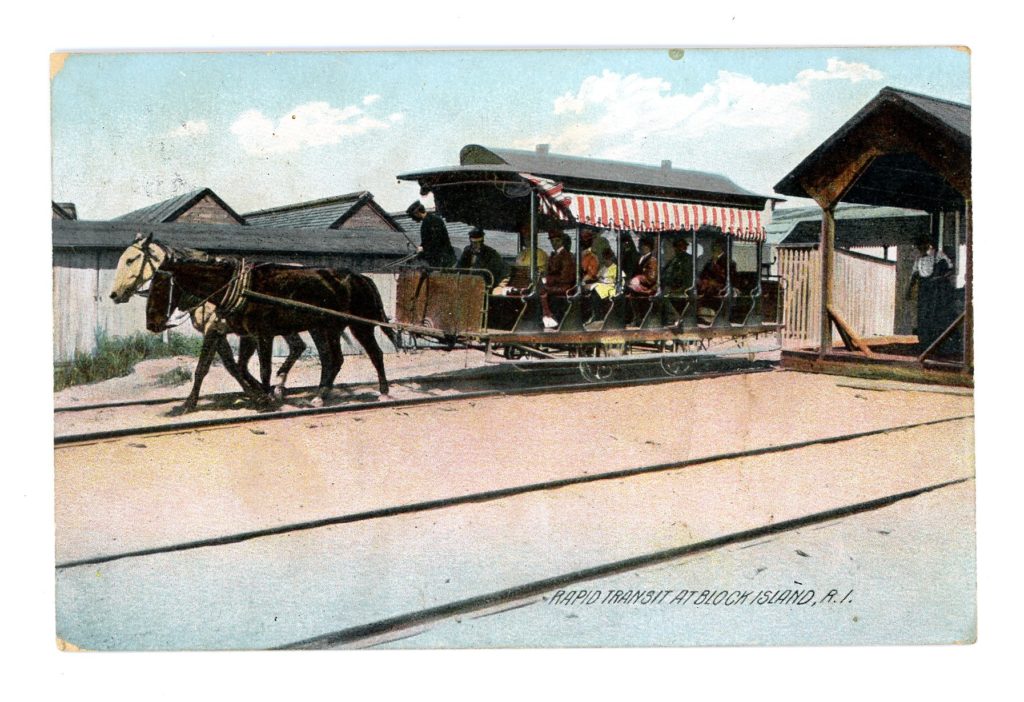

A driver drives a horsecar on Block Island, probably on a route between Old Harbor along current Corn Neck Road to the public pavilion (Sanford Neuschatz Collection)

Summertime was better for workers and patrons alike but pleasant weather also brought out another type of passenger, the public drunk. Intoxicated riders, especially on evening horsecars, harassed others and sometimes challenged the crew for control of the car. In response to numerous complaints, the state railroad commissioner recommended to the Union Railroad in 1876 to post a notice warning that “no disorderly, or otherwise obnoxious, person, whether under the influence of liquor or not, will be allowed to ride upon this car.” The public assigned the sobriquet “bartender’s carriages” to the last horsecars to leave Providence on Saturday evenings.

Official bromides did little to stem the problem of public intoxication in a rough-and-tumble society. Now that drivers could legitimately pass by potential troublemakers, ruffians often waited for the return trip to retaliate. One driver who ejected a drunk in 1881 at the amusement grounds of Spring Garden in Providence, confronted thirty to forty “toughs” on his way back. He brandished a revolver to scare them away. On other occasions, a vandal broke four horsecar windows before being subdued; another threw a knife at an employee; and “one dirty fellow, who deserved a beating,” attacked a conductor with a cane. Seeking police assistance did not always help either. One muscular passenger who tendered only five cents of a six-cent fare disarmed an officer and threw him from the horsecar. The conductor diplomatically refunded the nickel to the triumphant thug.

Accidents produced other headaches for horsecar crews. Children often jumped dangerously from moving vehicles. A five-year-old boy had a leg mangled by car wheels in 1879. One exasperated driver complained to a reporter in 1889, “I can’t hold the reins in one hand, keep my other hand on the brake, keep my eyes on the horses, ring up fares, answer questions of patrons, watch for passengers on side streets, and do other things that a driver has to do according to the rules governing our duties, and at the same time keep a sharp watch on children who steal rides to see that they are not injured.” The question of blame became increasingly important, as serious injuries proved costly. A woman crippled by an accident between two horsecars in 1880 sued and won almost seven thousand dollars. The company admitted that a brake rod snapped but stated it had no control over this defect.

John Wall, retiring in 1926 after thirty-eight years of railway service, reminisced about the old days when most passengers shunned litigation. Drivers on single-track lines often gambled at turnouts by going on rather than waiting for the next oncoming car. When the two cars approached head on between turnouts, one driver would place a stone or stick next to the rail and drive the car off the track while the other passed. “This would shake up the passengers somewhat,” Wall explained, “but they always laughed and were very good natured about it.”

[Banner image: Driver and conductor pose in front of red and green Cranston Street horsecar #92 in front of the stable and car house. The location of the photo is Cranston Street and Webster Avenue (Collection of Loris J. Bass)]