[From the Publisher: This article originally appeared on the New England Historical Society’s website at www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com. The New England Historical Society is similar to the Online Review of Rhode Island History, except that it covers all of New England (including Rhode Island). Dan and Leslie Landrigan do a terrific job publishing the website (and also authored the book Bar Harbor Babylon, Murder, Misfortune and Scandal on Mount Desert Isle, the cover of which appears on the right side of this page). We hope to share more of their articles with you in the future.]

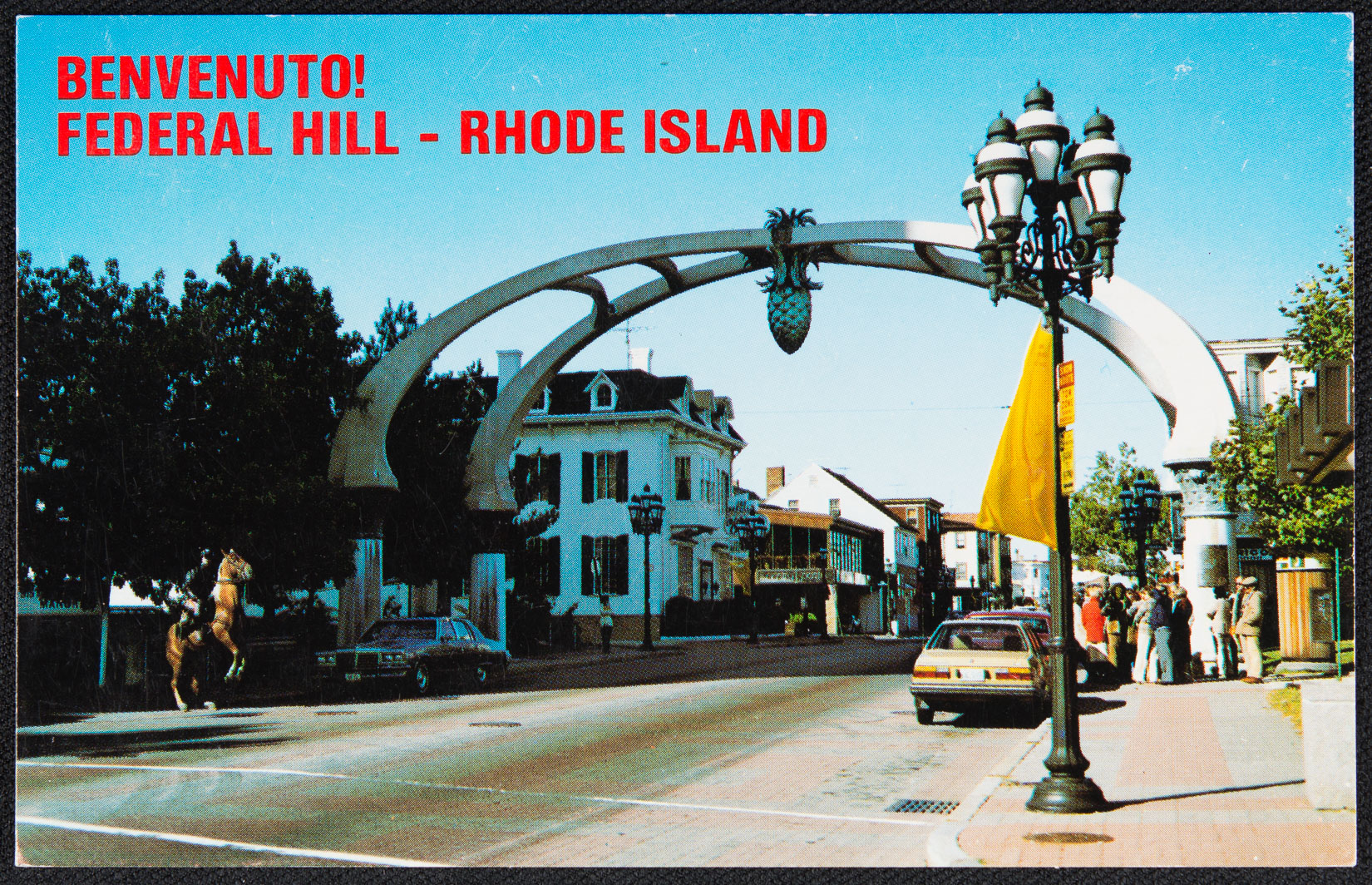

When a makeshift army in 1788 busted up a Fourth of July oxen roast at the base of a hill in Providence, Federal Hill got its name.

Originally, Native people called it Nocabulabet, meaning “land above the river” or “land between the ancient waters.”

Portion of a map of Narragansett Bay drawn by British mapmaker Charles Blaskowitz in 1777 (Library of Congress)

Providence grew up around the hill. Irish immigrants crowded into the neighborhood in the mid-19th century, followed by a wave of newcomers from Italy.

Today, Federal Hill makes up Providence’s Little Italy, known for its variety of restaurants and vibrant street life.

But things were very different in 1788.

Rhode Island Fails to Adopt U.S. Constitution

In June of 1788, New Hampshire ratified the U.S. Constitution, the ninth state to do so. That effectively established a framework for a government in the newly liberated country. Virginia followed, days later.

The Constitution, as created by the representatives from the original 13 colonies (and then states after July 4, 1776), stipulated that nine states had to approve it before it would be considered enacted.

As news spread that 10 colonies had signed off on the document, Federalists everywhere celebrated the news. In Rhode Island, July 4th seemed the perfect time to mark the new Constitution.

Rhode Island, however, along with North Carolina, declined to ratify the Constitution. Rhode Island would not approve it until 1790, when the adoption of the document was virtually a foregone conclusion.

Within the state, Anti-Federalists held power through the dominant Country Party. Anti-Federalists opposed the Constitution for a variety of reasons, including loss of independence to a strong central government. The party’s first leader, Jonathan J. Hazard of Charlestown, kept Rhode Island from sending delegates to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. The party’s leader, Arthur Fenner, won election as governor from 1790 to 1805.

After the end of the Revolutionary War, Rhode Island’s economy was in a shambles. It had huge war debts, in part because the British had occupied Newport and the rest of Aquidneck Island (and Conanticut Island) from December 1776 to October 1779. Rhode Island paid for three state regiments to keep on guard against enemy incursions, and paid for militia regiments that were called up to either try to dislodge the British army from Newport or defend against enemy attacks. The tax burden fell largely on the agricultural sector. But farmers had lost their main outlet to sell surplus farms goods—to British Caribbean islands. The state’s economy fell into the dumps.

The Country Party instituted a radial plan—having the state of Rhode Island print money. The money could be used by farmers to pay creditors. The new bills immediately depreciated in value. Creditors tried to hide in their basements when debtors came around to pay them with the new money. But under Rhode Island law, the creditors had to accept the payment as satisfying the debts.

Leaders such as John Adams thought that Rhode Island was engaging in dastardly behavior by printing money, which states would not be allowed to do under the new U.S. Constitution. But the scheme actually worked well for Rhode Island. By comparison, in western Massachusetts, indebted and angry farmers engaged in Shays Rebellion.

As plans for the July 4, 1788 celebration took shape, retired Rhode Island revolutionary war general William West would have none of it. West had commanded Rhode Island militia during the failed attempt by American forces to capture the British garrison in Newport in August 1778. West, now a prosperous Scituate farmer, businessman and judge in the state’s Supreme Court, gathered an army of 1,000 farmers and stormed Providence.

Federalists planned to read the Constitution during an ox roast celebration at the base of Nocabulabet . But West and his army showed up in protest and stopped the festivities.

Rhode Island Caves

Parties from West’s army and the Constitution-celebrating Federalists met to resolve the standoff. They reached a compromise to prevent fighting from breaking out: Federalists agreed that the celebration would only mark the Fourth of July. They would not read aloud the Constitution as planned. But Federal Hill got its name because of the incident.

For more than two years the Country Party held the Federalists at bay. The Country Party allied with many of Rhode Island’s Quakers, who opposed the federal Constitution’s allowance of slavery.

But the rest of the country pushed on, dragging Rhode Island inexorably toward ratification. Businesses could not seek payment for war losses, and other privileges were denied to states that did not ratify. And as a final carrot, the federal government agreed to assume state debts if they ratified.

In May of 1790, Rhode Island’s constitutional convention convened. Leaders in Providence threatened to secede from Rhode Island if the convention failed to ratify the Constitution. The Federalists then won and Rhode Island approved the Constitution.

By then, many debtors had paid off their debts with Rhode Island’s paper money. But that was not the case for everyone.

For West and other Anti-Federalists, opposition to the new Constitution would prove costly. The new government devalued state-issued currency. The bills could be exchanged for new government treasury bonds at an exchange rate of one percent of face value.

West then attempted to pay off mortgages on his Scituate farm in Continental dollars, but he failed because of a procedural problem with his appeal. The first decision ever made by the U.S. Supreme Court denied his attempts to use Continental currency. It doomed West to bankruptcy and he had a short stay in debtor’s prison. He died in relative poverty in 1816.