From 1861 to 1865, nearly 24,000 men served in the Union Army in Rhode Island units during the Civil War, or were credited to Rhode Island; approximately 2,000 of these men “gave the last full measure of devotion.” Before the war, Newport had been a favorite destination for Southerners to vacation to escape the hot summers of their plantations. While Rhode Island had gradually ended slavery after the Revolution, Southerners, with the passage of slavery protection laws (which was one of many catalysts leading to the war) could freely take their slaves with them to Rhode Island. Rhode Island’s most famous son of the time, Nathanael Greene had moved to Georgia after the Revolution, and was buried there. Many Rhode Islanders had family members in the South. In addition, Brown University was a popular educational institute for Southerners, some of whom joined the Confederate service. Furthermore, many mills in Rhode Island depended on the availability of cheap cotton to manufacture their goods, and other mills manufactured “slave cloth” for southern slaves to use as clothing. In essence, the Ocean State had a deep connection to the South.

Surprisingly, a handful of Rhode Islanders fought for the Confederacy in support of slavery and states’ rights. Among them were the sons of Richard Arnold, a wealthy planter who originally hailed from Providence and who owned plantations in Georgia. During one battle, Elisha Hunt Rhodes of the Second Rhode Island Volunteers found himself facing James R. Sheldon of Georgia, a former resident of Pawtuxet, whom Rhodes called “my old schoolmate and neighbor.” Private Henry Augustus Middleton was born in South Carolina in 1829; his parents were from Newport. He was mortally wounded at First Bull Run, fighting not far from where Newporter Theodore Wheaton King of the First Rhode Island Detached Militia was mortally wounded. The Civil War truly was brother against brother. A handful called the Ocean State home in the decades after the conflict and at least four are known to be buried here: these are their stories.

Samuel Postlethwaite, born April 6, 1833 in Mississippi, is the most famous of the Ocean State Rebels. His sister married into Rhode Island’s prominent Greene family. After reading a state-by-state guide to Civil War sites in 1990, Les Rolston, a Warwick building inspector and amateur historian was intrigued by the story of a Confederate soldier buried in Greenwood Cemetery in Coventry. He began doing research and found the remarkable story of Postlethwaite who served in Company D of the Twenty-First Mississippi during the war.

Wounded at Malvern Hill, Samuel went north in 1875 to seek relief from his war wounds. He died on August 20, 1876 and was buried in Greenwood Cemetery. In 1994, Rolston and several descendants of the family placed a government issued grave marker at Postlethwaite’s otherwise unmarked grave. The grave is the site of a Confederate Memorial Day ceremony each spring. Surprisingly, Postlethwaite’s grave is often marked by the United States flag, rather than the Confederate banner. This writer, as the descendent of several men who served in Rhode Island Civil War units, takes offense at this action, as this Confederate soldier fought against that flag for his own beliefs. Private Postlethwaite’s grave should be marked with a flag, as he was a soldier; but it needs to be marked with the proper colors, a Confederate emblem.

Rolston was honored by several historical groups for his efforts, and later published the book, Lost Soul: The Confederate Soldier in New England. A popular local history book, Lost Soul has gone through several printings and remains in print as a popular study of the war. Despite Ralston’s claims in the book, Samuel Postlethwaite is not the only Confederate buried in Rhode Island.

Anyone who saw the 1993 movie Gettysburg easily recalls the powerful performance of actor Richard Jordan as Brigadier General Lewis Addison Armistead. Jordan accurately played Armistead as a hardened West Pointer and Mexican War hero who resigned at the start of the war to join the Confederacy. Armistead struggled with his conscience on the night of July 2, 1863, when he realized the next day he would have to lead his men into battle against his best friend, Union Second Corps commander General Winfield Scott Hancock. In the end, Armistead bravely led his troops into action at Pickett’s Charge where he was mortally wounded and died two days later. For many viewers, the feeling about Armistead is that he was an old bachelor whose entire life was spent in the military. Despite this perspective, General Armistead left a son, Walker Keith Armistead, who called Rhode Island home.

Walker Keith Armistead, the son of Lewis Addison Armistead and his first wife Cecelia Lee Love, was born on December 11, 1844 in Dallas County, Alabama. He was named after his grandfather, who had graduated from West Point in 1803 and later became chief engineer of the United States Army. During the Civil War, Walker Armistead served as an aide de camp on his father’s staff and was with him at Gettysburg, but as he was not listed as killed or wounded. More than likely e did not follow his father into action at Pickett’s Charge. He later was a private in Company A of the Sixth Virginia Cavalry, often acting as a staff courier. Walker Armistead was wounded on June 29, 1864. While it has been written that Walker Armistead was with the Confederate cause “to the end,” his name is not listed among the parolees of the Army of Northern Virginia who surrendered at Appomattox.

After the so-called “close of the late Rebellion,” in 1871, Armistead married Adeline Appleton, the granddaughter of legendary statesman Daniel Webster of New Hampshire. Given his wife’s New England heritage and perhaps due to the fact that the southern post-war economy was a shambles, Armistead moved to the North to join Julia. Together they had three sons: Walker Keith who died in 1890 while on a hunting trip in Maine; Daniel Webster who lived until 1949 and later moved to Pennsylvania; and Lewis Addison, who was born in 1872 in New York City.

After his service in the Confederate Army, Armistead and his family moved to New Jersey, but in 1882 they built a residence on Gibbs Avenue in Newport. Here he worked as a court reporter and was known as an “expert stenographer.” In addition, Armistead served as president of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in Boston. Armistead died at his residence in Newport on March 28, 1898 and is buried at St. Columba’s Cemetery in Middletown.

Armistead’s son, Lewis, attended Rogers High School in Newport, and later became an executive of the Boston Elevated Railway Company. He spent many summers in Newport and died there in 1933. Serving his country, he volunteered for the Spanish American War and commanded a battalion of soldiers that he formed that was shipped off to Europe and fought in World War I.

Island Cemetery in Newport is one of my favorite places to explore. As a historian, I use cemeteries as an invaluable primary resource, often finding genealogical data and other information found nowhere else. Except for Swan Point and North Burial Ground in Providence, no Rhode Island cemetery contains as many famous characters of Rhode Island’s past as does Island Cemetery.

In 2009, while wandering through the rows of stones, I made a remarkable discovery. In a back corner of Island Cemetery, right along a fence line is the grave of Union Major General Gouverneur Kemble Warren, a former engineer and corps commander. On the second day of Gettysburg, Warren discovered the threat to the Union left and hurried troops to Little Round Top to save the day for the Army of the Potomac. He died in Newport in 1882.

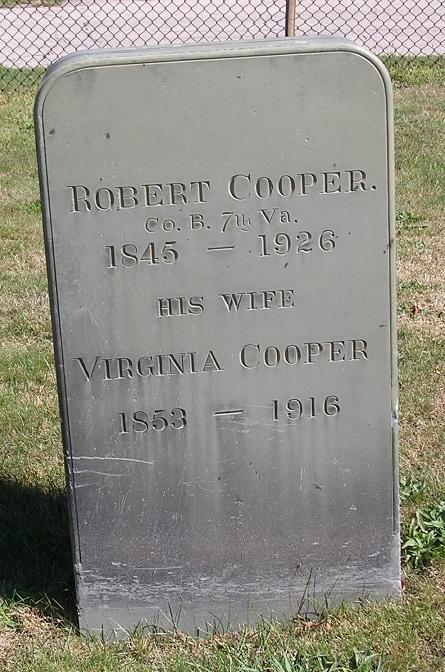

Not far from Warren’s grave, I spotted a large, rather unremarkable blue-gray slate stone with the name Robert Cooper engraved upon it. I was about to walk by when I realized to my great surprise that Cooper was a Confederate soldier! Below his name is the engraving “Co. B 7th Va.”

Robert Cooper was born in Virginia in 1845. He enlisted as a private in Company B of the Seventh Virginia Infantry on March 1, 1864. The Seventh Virginia had been slaughtered during Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg, but Cooper survived. His regiment spent the early spring of 1864 recovering near Drewry’s Bluff, Virginia, as part of Pickett’s Division, thus missing the carnage of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House. Cooper was present throughout the summer of 1864 with his company and was present at the Battle of Drewry’s Bluff and other actions as part of the Bermuda Hundred and Petersburg Campaigns. Cooper was sick in a hospital in Richmond on April 3, 1865, when the city fell to Union forces. He was turned over to the provost marshal and allowed to go home on May 28, 1865.

After the war Robert married a woman from Virginia named Virginia. At an unknown time they moved to Newport. He was in the city by 1879, as their first born child is buried in Island Cemetery. Two more children, Harry and Hattie followed, but they also died in childhood. Virginia followed in 1916. Private Robert Cooper died in Newport in 1926 at the age of eighty-one. As proud of his service in the Army of Northern Virginia, as the men who served in Rhode Island units buried around him, Cooper had his military service engraved on his stone for eternity.

A fourth confirmed Confederate soldier from Rhode Island is Dr. William Dixon Horton who served as an assistant surgeon in the Tenth Tennessee Infantry. Horton was born in Nashville on August 29, 1835. He attended the University of Nashville for his medical degree and obtained his doctorate in 1859. Horton joined the Tenth Tennessee as its assistant surgeon in the spring of 1861 and by December 1861 was serving at Fort Henry on the Tennessee River. When the fort fell to Union forces under Ulysses S. Grant on February 6, 1862, Horton was captured. Like most medical personnel, however, he was paroled to treat the wounded. Confederate records are often sketchy at best, but as far as the record indicates, Horton took no further part in the conflict.

In 1870 Horton was living in Memphis as the “City Inspector.” In 1875, he was back in Nashville and filed a U.S. patent for an “Improvement in Umbrellas.” By 1880, Dr. Horton had moved to New England and was residing in Providence, working as a physician where he was a boarder residing with his wife Annie, and daughter Edith. Horton later moved to Arlington, Massachusetts and on April 28, 1892 he sailed with his wife to Europe. He intended a “temporary sojourn” in Bern, Switzerland, but it turned out to last for several decades; there is no further evidence of Horton’s residing in Providence after the 1880 census. His wife Annie died in Bern in 1914. After the death of his wife, and with his daughter residing in London, he returned to Providence. Dr. Horton died in Providence in 1918. Why the city that he only resided in for a short time was chosen as his final resting place is unknown. His grave in North Burial Ground in Providence is marked by a large Catholic cross.

One Rebel who spent a great amount of time in Rhode Island is John Shea, but he is buried on the other side of the Pawcatuck River, in Connecticut. He was born in County Kerry Ireland in 1840 and by the outbreak of the Civil War was residing in Nashville. He joined Company C of the Tenth Tennessee Infantry, which served as part of the Army of the Tennessee. A post-war newspaper article claimed that Shea “served with valor throughout the conflict.” The record shows otherwise. Shea’s service file indicates that he was captured at Fort Donelson in February 1862. He took the oath of allegiance to the United States on August 30, 1862, and was released from prison at Camp Douglas, Illinois. He saw no further service.

Shea moved to New Haven, Connecticut and by 1878 had settled in Pawcatuck. Shea worked as a “quarry man” in the Westerly granite industry and also as a “fish peddler.” Shea died in 1916 after raising four children. He is buried in St. Michael’s Cemetery in Pawcatuck. In 1938, the United Daughters of the Confederacy sent a grave marker and Confederate battle flag to be placed on his grave. The local Westerly Sun declared Shea “the only Confederate veteran buried in New London or Washington Counties, as far as is known.”

Is there a possibility of discovering more graves of former Confederates in Rhode Island? Absolutely. After the war many Confederate veterans traveled all over the world. Some are buried in Europe, New Zealand, Japan, and Australia. One interesting fact comes from a 1912 booklet, Report of Commissioner for Marking Confederate Graves. “One Confederate prisoner of war died at Providence, R.I. but his remains were later removed to Cypress Hills National Cemetery, Brooklyn, N.Y.” An 1874 Decoration Day speech by a general at Fort Adams, printed in the June 1, 1874 edition of the Newport Daily News, alluded to a Confederate veteran buried in the Fort Adams Cemetery in Newport, but no confirmation has yet to be made.

Confederate prisoners were also housed at Portsmouth Grove Hospital on Aquidneck Island. Men who took the oath of allegiance to the United States were allowed to be released from prison. A local story abounds in Portsmouth of a Confederate soldier falling in love with a local nurse from the hospital, taking the oath, and eventually becoming a farmer in Portsmouth. If this story is true, his identity is unknown.

As the losing side in a bitter war, few Confederate veterans who moved to New England, with the notable exception of Robert Cooper, listed their military service upon their gravestone. Without such a notation, it is nearly impossible to distinguish Confederate graves from others. None of the known graves has distinguishing grave devices typically found on graves in the South, and none, with the occasional exception of Samuel Postlethwaite is marked with a Confederate flag. Doubtless additional Rebels rest under the rocky soil of Rhode Island, some in unmarked graves.

Although Rhode Island was staunchly pro-Union, some Rhode Islanders did fight for the Confederacy, while a few were marked to spend eternity in the Ocean State. Several local Civil War reenacting units portray members of the Confederate army. The South Kingstown High School sports teams are known as the Rebels. The team used to fly the Confederate battle flag and had a Confederate soldier for a mascot. Indeed, one yearbook from the 1970s featured an Army of Northern Virginia battle flag on the cover. In today’s politically fueled climate, the debate continues in South Kingstown about changing the name of the team to something else.

During the eighteenth century Rhode Island merchants took more slaves as cargo across the Atlantic Ocean than any other of the thirteen colonies. From 1861 to 1865 thousands of young Rhode Islanders went south to free the slave and reunite the United States as soldiers of the Union, and some died in this cause. Other Rhode Islanders fought to preserve slavery in a divided nation. It is a part of Rhode Island history that should not be forgotten.

[Banner Image: Confederates under General James Longstreet in an attack at Fort Sanders during the Battle of Knoxville in Tennessee, November 29, 1863 (Library of Congress)]

Additional Reading:

Additional reading: North By South: The Two Lives of Richard James Arnold (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1988) by Charles and Tess Hoffman is the best resource to understand the complicated relationship between Rhode Island and the South. It is the biography of a wealthy Providence merchant, Richard Arnold who owned plantations in Georgia.

Les Rolston’s Lost Soul: A Confederate Soldier in New England (Buena Vista, VA: Mariner Publishing, 2007) is a popular history of his search to document the grave of Samuel Postlethwaite. Despite Rolston’s claims in the three printings of the book, Postlethwaite is not the only Rebel buried in Rhode Island.

For additional information about the Armistead family, refer to Wayne E. Motts, “Trust in God and Fear Nothing:” Gen. Lewis A. Armistead, CSA. (Gettysburg: Farnsworth House, 1994).

The Confederate Compiled Military Service Records at the National Archives were consulted for each soldier listed to provide additional evidence of their wartime service.

The website www.findagrave.com is a great resource for discovering gravesites of Civil War soldiers.

The staff at St. Michael’s Cemetery in Pawcatuck filled in several details about the life of Michael Shea.