John M. Hay is perhaps Brown University’s most illustrious undergraduate. He started his career as assistant secretary to President Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War. His photographs alongside Lincoln have been published in hundreds, if not thousands, of books over the past century-and-a half. And his accomplishments during his career (both civilian and political) have been well documented. During his illustrious career, Hay served in a variety of diplomatic positions, as a night editor of the New York Tribune, as Assistant Secretary of State, and as Ambassador to Great Britain under President William McKinley, before rising to Secretary of State in the same administration. He was so respected in this position that he continued in the same role under President Theodore Roosevelt. As Secretary of State, he helped to open China to free trade and to end the war between Russia and Japan. But where did it all begin and what are the particulars that tie Hay to Rhode Island?

John M. Hay was born on October 8, 1838, in Salem, Indiana. The third child of Dr. Charles and Helen Hay, John’s early life was spent in a small one-storied brick house of which he would have no memory later in life. Seeking a better existence, in 1841 the Hay family moved to Warsaw, Illinois, a frontier settlement on the banks of the Mississippi. Here, John and his siblings spent their youth.

During his toddler days, John learned to string words together in rhymes; at the tender age of seven he was learning German. While still a young boy, he told his brother that he saw and heard a ghost in the basement. According to John, the presumed ghost asked: “Little Master, for the love of God bring me a drink of water.” Scared out of his wits, he ran upstairs and locked himself in his room. The next morning, John told his father about the incident. Turns out, John did see and hear something, not a ghost, but something that seemed to be an apparition in a young boy’s eyes. What he saw and what he heard was actually a runaway slave who had been wounded during an escape. Dr. Hay, John, and John’s brother Leonard went downstairs and found an area where someone had made a makeshift bed along with an eighteen-inch diameter bloodstain. John never forgot the incident; it solidified his anti-slavery views for the rest of his life.

When the time came for a primary education, John and his brother were schooled by an Episcopal clergyman. Two of their main subjects were Latin and Greek. In 1851, John was sent to a private academy in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Here he met John G. Nicolay, six years his elder and a Bavarian by birth. They hit it off immediately, especially because Hay spoke fluent German. Hay and Nicolay became good friends. They would meet again less than a decade later where each would eventually play significant supporting roles on a much larger stage as secretaries to President Abraham Lincoln during the tumultuous Civil War years.

The following year, Hay attended a college in Springfield, Illinois, which was more a preparatory school than a college. With Springfield as the capital and the seat of the state legislature, young Hay would see men like the rotund Senator Stephen A. Douglas and a tall lanky lawyer who was developing quite a name for himself: Abraham Lincoln. By 1855, Hay was destined for bigger challenges. He had already gained the respect of his classmates. Nonetheless, when time came for celebration, Hay could also saunter with the best; he picnicked, partied, and danced. Though young Hay must have had some say about his future education, scholars say his parents made the decision that he should attend Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, where Mrs. Hay’s father, David Augustus Leonard, had graduated some sixty years earlier having delivered the class poem at commencement in 1792. Though founded as a Baptist institution, Brown’s charter provided the assurance of a non-sectarian education and “a full, free, absolute, and uninterrupted liberty of conscience” that is proudly adhered to this day.

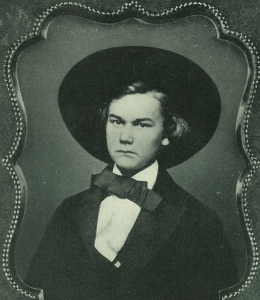

On Friday, September 7, 1855, just one month shy of his 17th birthday and despite his youth, Hay became a member of Brown University’s junior class. The student body then consisted of 225 classmates, with 9 professors as educators. In a letter home after his safe arrival in Providence, Hay told his parents, “I had a whirling, hustling time on the way here, but at last arrived . . . safe and sound in everything, except my eyes, mouth and ears were full of cinders and dust.” In the following paragraph he commented about settling in and registering for three classes: “Chemistry, Rhetoric, and Trigonometry.” Further, he explained that, “We also have exercises in speaking and writing essays.” But what is evident in this first letter home from college is Hay’s maturity: his willingness to adapt to new surroundings and his desire to grasp the opportunity and succeed intellectually. Hay also demonstrated the sense of humor that would sustain him throughout his life when he closed the letter by sending his love to “Grandpa, aunts, uncles, cousins, and cats . . . ,” adding a postscript, “Somebody write soon – soon – do you hear? SOON.”

Hay, like other boarding students, was assigned a “conveniently furnished apartment.” His was located in Room 19 on the second floor of University Hall, a building that was constructed in 1770. The city he would call home for the next three years was founded by Roger Williams in 1636. Providence was the second largest city in New England with a population of some 50,000. Hay quickly adapted to the city, the cultural and religious diversity of the students from all over the country, and the high quality of the faculty.

At Brown, Hay not only stood out because of his intellect but also because of his dress. Unlike classmates from the eastern U.S., his looks and appearance carried a “western” influence. Beside Hay’s obvious intelligence, his wit, friendliness, and love of humor (especially a good joke), made him an instant favorite among his peers. He was called “Johnny” by his intimate friends. But they also noticed something else about their friend’s nature; his bouts with depression. Periods of melancholy would haunt Hay for the remainder of his life.

In November of his first year, Hay convinced his parents to allow him to drop down a class and become a sophomore, not because he was having difficulty with his studies but as he said in a letter home: “[I]f I go through so hurriedly I will have little or no time to avail myself of the literary treasures of the libraries,” while adding the that “This is one of the greatest advantages of an eastern college over a western one.”

Hay came to Brown at an advantageous period. The new president of the university, Barnas Sears, relaxed many restrictions pertaining to campus life. No longer were student rooms subject to daily inspections, and fraternities and literary societies were established.

In the ensuing years, Hay studied Latin, Greek, mathematics, the classics (French and German), and sciences such as chemistry, physiology, and geology. Political economics was also part of his curriculum and according to school records, under Professor William Gammell, this is where he excelled. He also loved literature, especially poetry. Striving for success, his writing achievements earned him the reputation as the “best undergraduate writer in college.” During the first terms at Brown, his busy schedule caused him to limit his extracurricular activities. In a letter home, Hay wrote, “I have no acquaintances out of the college; consequently, [I] know little of the city.” Using his unique sense of humor, he closed the letter writing several postscripts, the last written as “P.P.P.P.P.P.S. That is all.”

Yet, he eventually found time to attend a Republican meeting in Providence sometime during the spring of 1856. Writing home to his uncle John Milton, while thanking him for his financial support, Hay also found it necessary to tell him that “Political feeling is running very high in Providence at present . . .”

Students at Brown were required to memorize a score of passages from textbooks. A student related: “Hay put his book under his pillow and had the contents thereof absorbed and digested by morning, for he was never seen [doing anything] that could be construed into hard study.” Today he might be considered a man with a photographic memory.

As the college years flew by, Hay, like so many of his peers, admired pretty girls, perhaps at a distance until he mustered the courage to approach them. He also pledged to a fraternity, became the vice-president of a literary society, and served as editor of the Brown Paper, an undergraduate journal. But his gift for poetry was never more apparent then when he read his own poem, “Erato” to an audience on Class Day, June 10, 1858. Described at the time as “a fertility of conception, a depth of sensibility, and a power of poetic expression,” his words were rarely equaled at any future literary gathering.

But all good things must come to an end. That evening, Hay packed for home. The following day, he left for good. The wait for commencement exercises to be held that September seemed long and his pining for home was too great. Hay would not return to Brown University again until 1897, when he received a Doctor of Laws honorary degree.

After returning home in 1858, Hay was faced with a career choice. He was torn between finding employment in the literary field or the pursuit of law. He even thought about the ministry. Unable to make a timely decision, Hay again fell into melancholy. Part of his depression might have been the result of his transformation from a “Westerner” to a gentleman of refined culture. “There is, as yet, no room in the West for a genius,” as Hay told it – most assuredly, referring to his own high intellect in a land where brawn held considerably more leverage than brains.

In the end, Hay chose the legal profession. His uncle Milton had a well-established practice in Springfield and welcomed his nephew into the firm. Next door was Abraham Lincoln’s law office. They met mostly in passing but were familiar with each other. Lincoln, a former Whig, was now a Republican; “the party of the zealous young men in the North, who were resolved to prevent further encroachments by the Southern slaveocracy,” Hay would write. The party ideas and platform appealed to young Hay and he, too, joined the party.

John Nicolay, Hay’s friend from their days together as students in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, operated a newspaper in Springfield. Lincoln enjoyed reading Nicolay’s writings. When Lincoln made his run for the Presidency, he wisely chose Nicolay as a secretary during the campaign with Hay serving in the background. Shortly after Lincoln was elected, he appointed Nicolay as his private secretary. Soon Nicolay was inundated with secretarial duties far beyond what he initially envisioned. He needed help and knew just the man to lessen his load: John Hay. He approached Lincoln with the idea of bringing Hay to Washington, DC. Lincoln’s first response was classic: “We can’t take all Illinois with us . . .” But after a pause, he relented: “Well, let Hay come.”

The rest, as they say, is history.

As in his letters home to his parents while at Brown, and before closing this brief treatise, it is appropriate to add this postscript that defines Hay’s profound impact and lasting impression he made upon others. In 1910 at the dedication of the John Hay Library at Brown University in Providence, Elihu Root, Hay’s successor as secretary of state, reminisced: “He was the most delightful of companions. One found in him breadth of interest, shrewd observation, profound philosophy, wit, humor, the revelations of tender and loyal friendship and an undertone of strong convictions and now and then expressions of a thought that in substance and perfection of form left in the mind the sense of having seen a perfectly cut stone.”

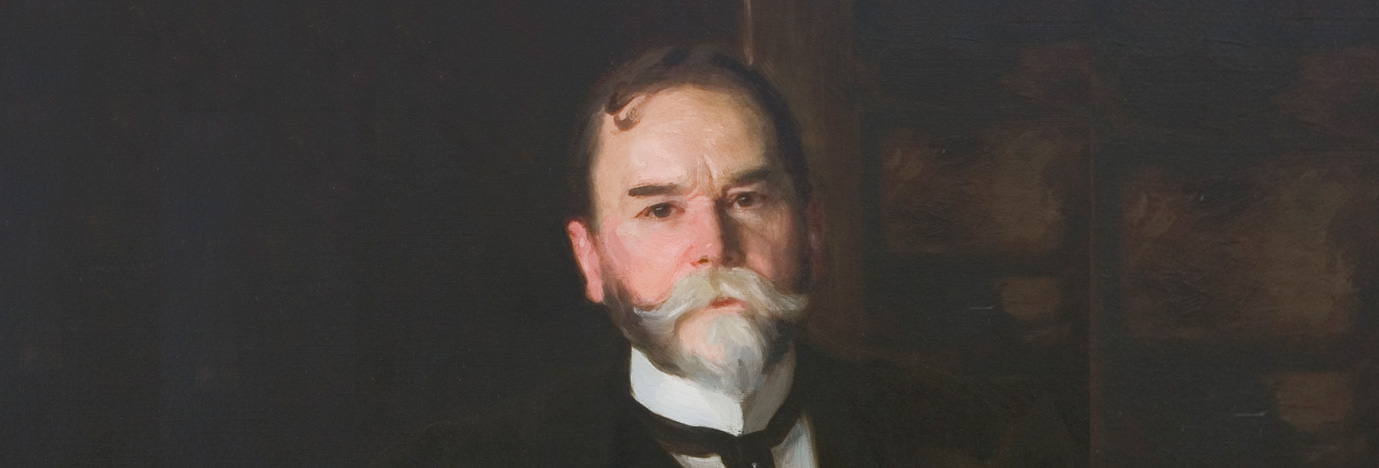

[John Hay painted by John Singer Sergent, now hanging at the John Hay Library (Brown University Portrait Collection)]Suggested Reading:

This story first appeared in the author’s book, Hidden History of Rhode Island and the Civil War (History Press, 2013). More fascinating details about John M. Hay can be obtained by reading, The Life and Letters of John Hay, Vols. I & II, by William Roscoe Thayer and published by Houghton Mifflin Company in 1915. Though written in the flowery literary style of the period, the volumes are crammed with meaningful anecdotes and captivating history. A more contemporary biography by John Taliaferro, All the Great Prizes: The Life of John Hay, from Lincoln to Roosevelt, published by Simon and Schuster in 2013, is also highly recommended. For the amateur historian and literary adventurist, the John Hay Library on the campus of Brown University stores a vast assortment of books and over 9,100 personal papers from John Hay’s bountiful collection. With a dedicated staff of research librarians, it is well worth the visit.