I was nine years old when the war started and fourteen when it ended, so these memories are through the eyes and ears of a youngster. It was also only the summer months I spent in Rhode Island, and not in Newport, but the opposite end of the state – Watch Hill.

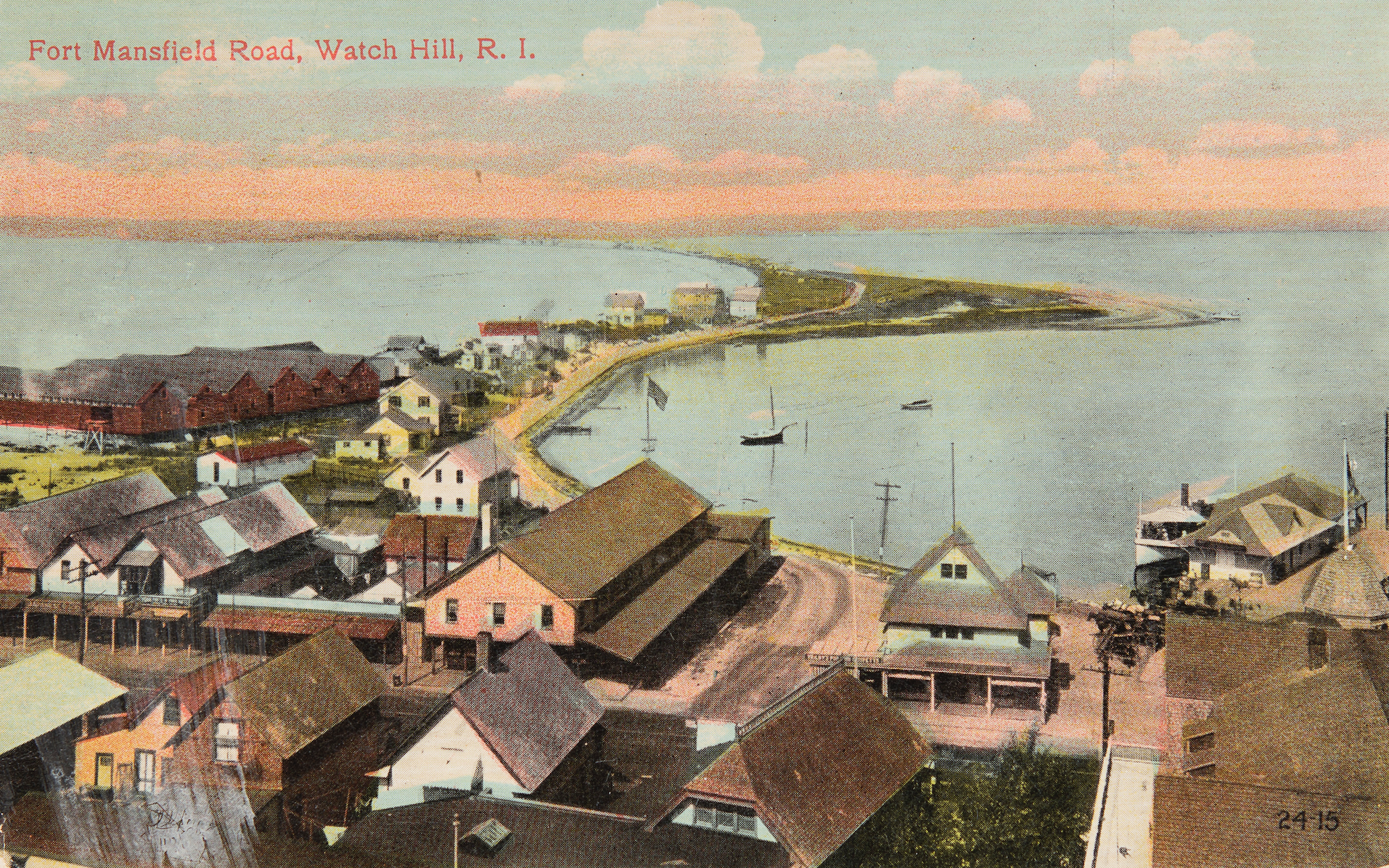

My grandfather bought a cottage in 1918 at Watch Hill on a narrow peninsula jutting out a mile and a half between the Atlantic Ocean and Little Narragansett Bay. On maps it is called Napatree Point, but the locaIs called it Fort Road because Fort Mansfield was at the end of it, built during the Spanish-American War to prevent any naval attack on New York City. There were thirty-nine houses along this spit of land, and his was the sixth from the far end.

From the time I was six months old my family and I spent every summer there until the 1938 hurricane changed our lives. All thirty-nine houses were completely destroyed with fifteen fatalities including my aunt and step grandmother. Fortunately, the rest of my family and grandfather had left two weeks before the September storm. My father, of course, was devastated, having lost his sister and step-mother. By the time he arrived, all of the bodies had been found except for his sister. He spent eleven days searching the Connecticut shore before she was found, and later wrote a book called The Search about his experiences. [1]

It was four years after the hurricane before we returned to Watch Hill. Instead for those four summers we stayed in a wonderful cottage high on a hill in Misquamicut called The Acorn. It had that name because it was next door to the Oak Inn. During World War II there were mounts for 155mm artillery nearby, up an unpaved 1/4 mile hill road off the Misquamicut Shore Road near where Newbury Drive is today.

A 155mm artillery piece, of the type that was at Oak Hill during World War II (Wikipedia for Oak’s Inn Military Reservation)

Meanwhile, at Watch Hill, many summer residents refused to return and the little community there remained in mourning. There were “For Sale” signs everywhere and large houses could be bought for almost nothing. My father bought an abandoned Victorian style house with seven bedrooms, five bathrooms, and furniture for $2,500. It was a fixer-upper with great potential, and located on high ground above any future storm surges.

My neighbors and I played at Fort Mansfield as teenagers. On the 4th of July we would divide the Watch kids into two teams, one to defend the fort and the other to attack. We somehow survived unscathed each side shooting rockets, fire crackers, roman candles and an occasional cherry bomb at the other side.

Fort Mansfield Road, leading to the beach at Watch Hill, Napatree Point, and Fort Mansfield (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)]

In 1942, we had changed the window shades facing the ocean to black ones and pulled them down at night. There had been German U-boats off the coast, and many of our ships had been sunk. A Coast Guardsman was constantly patrolling the beaches day and night. I remember seeing several life jackets, fruit crates, and other ship debris along the shore. Our cars had black tape across the headlights except for a very narrow vertical strip to allow a little light to get through. Gas was rationed and a stamp with a letter A, B, or C was attached to the windshield. Lucky were the ones having a B or C, as they were given more gas because of their importance in the war effort. Certain foods were rationed. No one could buy a good piece of steak, and almost no sugar or butter was available.

Many of the houses had service flags hanging in their windows. A blue star in the flag’s middle signified a family member in the military. A gold star meant killed in action. Unfortunately, as the war went on, I saw more and more gold stars. I remember a few who were five or six years older than I who died. Larry Enwright, our milkman’s son, enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps and was killed in action. David Jones, who lived in the house behind ours, was also killed.. Tom Walker, who would run up and down the beach with his German Shepherd dog almost every day, volunteered and became a pilot. He died in training. I sadly remember, after he died, any time a plane flew over the beach his dog would race and bark after it. Billy Ackerknecht, a close friend of my family, died in the Battle of the Bulge. I remember sitting on the beach with his parents when they got the word he was being sent overseas. His mother cried.

Shortly thereafter, my older brother and first cousin enlisted in the navy. My parents gave me a large map of the Pacific that I placed on my bedroom wall. I pinned little American or Japanese flags on the islands or territory occupied by each.

On a hot summer day in 1944, I corralled a group of my friends to go dig some clams. The best place was out at the end of Fort Road, on the bay side just before the forts. The Peninsula ended in a sharp bend, called Sandy Point, making a nice little cove for clam digging. Besides my younger sister Jane and me, our group consisted of: Gracie Ackerknecht, the younger sister of Billy who, as I mentioned, was later killed in the war; Dick Joy, the grandson of the founder of the Packard Car Company; Jan Wemple, my future brother-in-law; and his sisters Sallie, age 10, and Dinny Wemple, age 13, my future wife.

My mother gave us her favorite aluminum pot in which she would cook lobsters, but only on condition we take very good care of it. Aluminum was scarce during the war. Our small group, in bathing suits, walked the mile and a half of beach out Fort Road where houses once stood. There were only sand dunes, patches of dune grass and an occasional piece of concrete or brick from part of a sea wall, chimney, or foundation left over from the hurricane.

Arriving at the cove about noon, we waded in up to our waists and started feeling for the buried clams with our bare feet. If the sand felt hard, or we saw an air hole we reached down and dug with our hands. We kept the pot afloat and dumped our catch into it. On the beach, about fifty feet from us, was a big white sign: “WARNING – KEEP OFF – NAVAL PRACTICE BOMBING AREA.” Near the sign were rusting stove-pipe size crumpled “bombs” filled with sand. We were in the water and not on the beach, so we thought we were safe.

Watch Hill Beach walking towards Watch Hill from Napatree Point, September 2017 (Christian McBurney)

This quickly changed when we found, under water, several heavy, cast iron, foot long “bombs,” with fins. I picked up two of them and thought they would make great souvenirs or door stops. I noticed in the center of each bomb a hole with colored powder, which would indicate to the bomber where the bomb was located. Then I realized we were clamming in the bull’s eye of a water target.

In the distance we could hear the sound of a high flying plane and hoped it was a commercial passenger plane, but then terror struck. Looking up towards the sun I could see just the wing tips of a plane diving towards us. Splashes of water appeared all around us. Couldn’t the damn fool see us in the water? We dropped everything and tried to run to shore. It is almost impossible to run in waist deep water. We were moving in slow motion. Next, a second plane dropped its load followed by a third, and then a fourth screaming diving plane. I don’t know whether our screams or those of the dive bombers were louder. I could see the gull shape wings as the half dozen planes pulled out of their dives right over our heads. The cast-iron practice bombs appeared to weigh about five pounds, had fins with a shaft down the middle, and were filled with some colored powder to show where they hit.

I saw Gracie trip and fall near me and thought she must have been hit, but once the raid was over, we saw no one was hurt. We managed to get back to the beach and ran away from the area as fast as we could. Someone said my mother’s prize pot was missing and we should go back and find it. No one volunteered.

We found out later that the pilots had been training at the Naval Base in Charlestown, Rhode Island. They were flying TBM Avengers with night fighting radar. Night Fighters, as they were called, lived a very dangerous life, training at night and in bad weather. More pilots were killed in training there (forty-four) than in combat. One of the new pilots was George H.W. Bush, and I often wondered if he was one of those who bombed us. They were flying by primitive instruments and radar, and it is no wonder they did not see us. As far as I know, we were the only Americans bombed during the war in the U.S.

News arrived in early August 1945 about the dropping of the atomic bombs and it was shortly thereafter, on August 15, that the war was over. The celebration began. We youngsters were allowed to ride on the fire trucks through the local towns. The crowd waved and cheered us we drove by with sirens blazing, flags waving, and streaming rolls of paper behind. It was a day to remember. Rhode Island later called the anniversary V-J (Victory over Japan) Day. It was the only state to declare it a holiday and is now called Victory Day.

[Banner Image: Fort Mansfield Road, leading to the beach at Watch Hill, Napatree Point and Fort Mansfield (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)]

Sources:

[1] Moore, Paul J. The Search, An Account of the Fort Road Tragedy. Available at amazon.com as a Kindle edition, 2011.