Questions for Christina Alvernas and Her Answers

1. Tell our readers briefly about yourself and your role at MHS.

I am a 2007 graduate of Salve Regina University’s Cultural and Historic Preservation program with a minor in History. I’ve worked for many non-profits and museums in Rhode Island and Massachusetts over the years, and jump at the chance to research and write about history. I am also an avid genealogist and earned a Certificate in Genealogical Research from Boston University’s Center for Professional Education in 2015.

I came upon my role at the Middletown Historical Society completely by chance. In December 2015, I was in between jobs and reached out to the organization in search of volunteer opportunities. MHS immediately put in touch with Ken Walsh, the society’s director of research. At the time he was already working with Salve on the project but needed someone who would be around beyond the school year, to help pull all the pieces together and see it through. I ended up becoming the editor and lead writer. Ken wrote the technical chapters, Salve students wrote most of the appendices, I wrote some of the chapters that provide historical context and then integrated everyone’s work into the completed 364-page report. Ken and I ended up making a really great team and after the project was complete, he wanted to make sure I stayed involved, so I am now a proud member of MHS board of directors.

2. Can you please summarize the siege that occurred in Middletown outside Newport in August 1778?

The Siege is a portion of the larger Rhode Island Campaign, which was the first American and French joint military operation of the American Revolution. It got off to a messy start and never really recovered.

In an effort to oust the British from Newport, the allies had planned a joint attack. The Americans would descend on Newport by land, while the French would bombard it by sea, trapping the British between them. This all changed when Admiral Howe’s fleet was spotted off Point Judith. French Admiral d’Estaing began to fear his fleet would be trapped in Narragansett Bay, so he abandoned the plan and headed out to fight Howe on the open ocean. Unlucky for him, a hurricane hit in the middle of all this. Meanwhile, after weathering the storm in Portsmouth, General Sullivan (leader of the American forces) decided to march his army toward Newport and begin the Siege alone. At this time, he assumed d’Estaing’s ships would defeat Howe and rejoin the Americans to complete the operation. He began the Siege with this assumption and was counting on French involvement to insure its success.

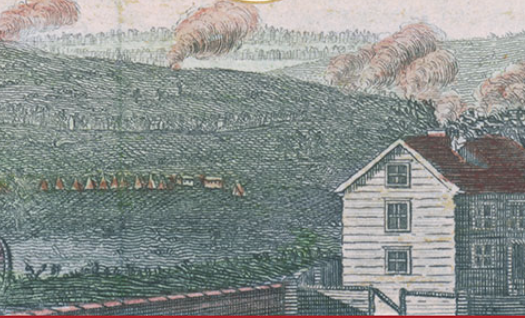

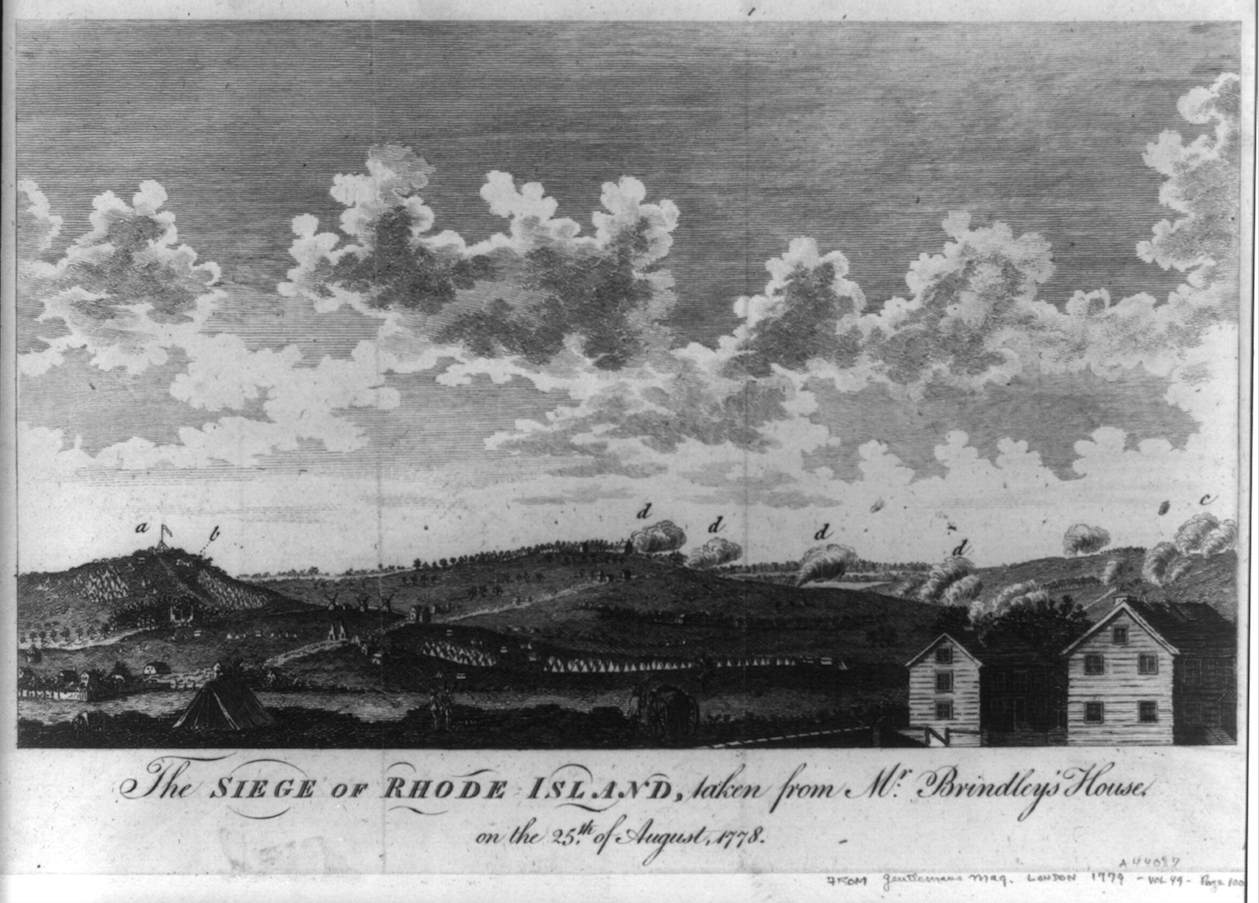

“The Siege of Rhode Island, taken from Mr. Brindley’s House on the 25th of August, 1778.” View from Newport looking north. The areas marked (d) represent British artillery firing from their front lines. The area marked (c) shows artillery rounds exploding on American-occupied Honeyman Hill in Middletown (Library of Congress)

The British had a stretch of defense works high up on Bliss Hill in Middletown, to the west of Easton’s Pond. To take aim at this, Sullivan positioned his army to the east of Easton’s Pond, in an area known as Honeyman Hill. The two sides cannonaded each other for days on end, over the pond and valley between them. Under normal conditions, the Americans could have made an attempt to cross the valley and penetrate the British lines, but at this time Easton’s Pond was overflowing from the recent storm. Any chance of crossing was now virtually impossible. Their only option was to continue to cannonade until more help arrived and although they were hitting their targets, they were not seeing the results they were hoping for.

Eventually word from d’Estaing arrived, much to Sullivan’s dismay. The French fleet had been so severely damaged in the storm that they were headed to Boston for repairs and would not be able to participate in the Siege. The Americans continued to expand their trench works and fire on the British but still to no avail. Without the backup they had been counting on, and upon hearing news of impending British reinforcements, the Siege was abandoned and the Americans headed up the island back to Portsmouth. There they became entangled in the Battle of Rhode Island and ultimately completed their retreat to the mainland a few days later.

3. Why did the MHS undertake this project?

Although I was not involved when the decision was made, I think it was for a number of reasons. After years of reading up on and studying the Siege, Ken had noticed things that an engineer could analyze in a way that a historian could not. It just didn’t make much sense that the Americans continued to hit their targets along the British outer line but never really had anything to show for it. Ken’s cannon study was a great way to bring history and science together to answer a question.

Another reason was the longstanding misidentification of the fort on Vernon Avenue. In the 1920s it was believed to be the British Green End Fort (also known as Card’s Redoubt), which in actuality is sitting in a pine grove on nearby private property. A stone marker was placed at the site by the Newport Historical Society at the time, identifying it as “Green End Fort Built 1777 By the English for the Defense of Newport.” At that time, the mistake was easy to make because the Diary of Frederick Mackenzie—an invaluable day-to-day account written by a lieutenant in the Royal Welsh Fusiliers stationed at Newport—had not yet been published. There is an image, drawn by Mackenzie, that first lead Ken to suspect the Vernon Avenue fort had been misidentified. Despite new information, the existence of the stone marker has helped to perpetuate the old theory. We were hoping to rectify this.

Most importantly, the Siege happened right here in Middletown and is one of the most significant moments in the town’s history. At the time, all eyes were on this event in the hopes that it could be a follow up the American victory at the Battle of Saratoga, and perhaps even end the war. As part of the larger Rhode Island Campaign, it was also the first joint military operation between the Americans and French, and was one of the largest campaigns of the entire war. It is frequently overlooked in accounts of the American Revolution, most likely due to its outcome. Locally, the leg of the campaign that happened in Portsmouth, the Battle of Rhode Island, tends to get the attention and has been properly commemorated with plaques and memorials. Without the Siege however, you would not have had the Battle as it played out. So the MHS decided it was the right time for an in-depth look at the Siege specifically and Middletown’s role in the Revolution.

4. Talk about the cooperation between MHS and Salve Regina.

By the time I came into the project (January 2016) much of the work done by the students was nearly complete. Students in the History Department and the Cultural and Historic Preservation program at Salve Regina had spent most of the fall semester digging through old newspapers, reading Washington’s letters, working with maps, and doing Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) surveys. They had done so much work and such a wonderful job that we ended up including several students’ completed work as full appendices toward the end of the report, rather than use bits and pieces of their research in the main text. The faculty members involved were also so helpful on this project. Dr. John Quinn, Professor and Chairman of the History Department, worked as our main contact with the university. He wrote the preface, endlessly proof read chapters for us, and offered great advice throughout the process. Dr. Jon Bernard Marcoux, archaeologist and Assistant Professor in the Noreen Stonor Drexel Cultural and Historic Preservation Program, helped a student map the battlefield, conducted the GPR survey with his students and provided a written report on their findings. Ken and I are both Salve alumni, so it was rewarding for us to work with current students and our former professors on this project. Since it was such a Salve effort, a group of us came together in December and formally presented a copy of the completed report to Salve’s president, Sister Jane Gerety.

5. Was it important to obtain the federal grant? How did the team qualify for it?

As Ken explained to me, this project involved such a substantial amount of detailed research, it could not have been accomplished by a small group of volunteers. With the grant, we were able to pay a number of trained investigators, including students, faculty, and engineers, to help analyze the large volume of available data and produce the report in roughly a year. I can vouch for this first hand. The fact that there was grant money, meant that I could afford to be so involved. It allowed me to fully commit my time and dedicate myself to the project in a way I never could have done if I were merely volunteering.

There were a few reasons we were awarded the grant. One being the subject matter. The fact that there was this conflict in the American Revolution, that no one else had looked at in this way, really helped. I think the fact that Ken was the person submitting the grant application was another big factor. He is the MHS Director of Research but also has 43 years of experience in managing Federal research projects and producing successful proposals. He promised the National Park Service we would have a 300-page report complete in roughly a year and in the end we submitted a 364-page report, on time and under budget.

6. What was the goal of the MHS in preparing the report? What is left of the original sites?

The Americans had cannonaded the British for days to no avail, which seemed odd. So our main focus was to determine just how much the type cannons, the geography of the battlefield, and the fortifications they were firing on, effected the outcome. Ken’s cannon study also resulted in a MATLAB code (which we provided in full at the end of the report) that other engineers can apply to study similar problems on other battlefields. Also, since our grant was from the American Battlefield Protection Program, the NPS wanted to make sure we covered what happened to the forts and battlefield after the war, and what is left today.

The American trench works on Honeyman Hill were filled in by the British in the fall of 1778. There are nineteenth century accounts that evidence of the American position was still visible. At the time the area was farmland but it has since become developed. Whatever traces were left of these works are now long gone, although British cannon balls have still been found in backyards in this area.

The interesting thing about the British works is that they were destroyed as well. When the British abandoned Newport in October 1779, they ruined their own forts and burned their barracks and other woodwork before leaving. The French army under Rochambeau, after arriving in July 1780, rebuilt the British forts and constructed additional defenses of their own. Accordingly, any fortifications left after the war were either refurbished French versions of British defenses or brand new French forts. All that being said, remnants of Card’s Redoubt and Tonomy Hill Fort still exist but overgrowth of vegetation has not helped. The Redoute (French for Redoubt) de Saintonge, the one frequently mislabeled as Green End Fort but in actuality newly built by the French in 1780, is in beautiful condition. It exists today for a number of reasons. One, it never saw action. Two, it was assumed to be a British fort (and used in the Siege) and thus was purchased in the late nineteenth century in an effort to preserve it. Three, it is owned by the Newport Historical Society but maintained by the Rhode Island Society of the Sons of the Revolution, who have taken wonderful care of it.

Forts aside, there are other existing landmarks that would help orient people who want to recognize the battlefield today. Bodies of water such as Bailey’s Brook, Easton’s Pond, and Easton’s Beach are still there. Also the two hills that played such an important role in the Siege, Bliss and Honeyman, although largely developed today can still be seen. Other landmarks such as East and West Main Roads, used by Sullivan to march his army up and down the island still exist and follow the same path they did in the eighteenth century. The John Bliss House, just over the border in Newport, was used as the British field headquarters during the Siege and still exists today as a private residence. It is also thought to be the oldest house in Newport. Unfortunately for Middletown, many of its colonial era farm houses located in or near the Siege did not survive the war. Most were destroyed by the British in the lead up to the Siege, to prevent the Americans from using them as shelter.

7. How would you like to see the Siege of Newport memorialized? What is the next step?

The MHS owns a parcel of land on the corner of Valley Road and Green End Avenue in Middletown. It is situated right along the banks of Easton’s Pond, between the hills where the American’s and British were entrenched. We’ve talked about using this space to commemorate the events of August 1778 in one way or another. One idea was building a small museum; another was to erect some kind of memorial or plaque on this site. But due to lack of funding nothing has been officially decided.

Excerpt from a map by a British officer, Edward Fage, in 1779, showing positions of various British forts used in the defense of Newport. Note that there is no fort or redoubt at Vernon Avenue.

Whatever MHS ends up doing, I think just the fact that MHS owns this land makes it such a wonderful asset. I think it would be a great space to occasionally offer an outdoor talk on the Siege a Sunday afternoon, where the speaker could point up at Bliss Hill and then at Honeyman Hill, and really put people right at the heart of the Siege. Ideally, I think that would be the best way to commemorate it. Yes, have some kind of physical memorial, but also just to use the space in a way that would help people understand what

8. What was challenging about preparing the report? What did you enjoy about it?

Obviously, pulling together a report this size was challenging in itself but the most challenging part for me, being a history person and not an engineer, was dealing with Chapter 2. That is the part that covers Ken’s cannon study. It’s so technical and detailed that I was nervous about editing that portion so we ended up enlisting the help of a recent Roger Williams University graduate, Drew Canfield. As an engineer, he had enough of an understanding of the material to properly edit that chapter, leaving me free to worry about the rest of the report. I still can’t thank Drew enough.

As far as what I enjoyed, there was so much. I absolutely loved getting to know the story of the Siege and larger campaign in great detail. It is so fascinating and doesn’t get the attention it deserves. Being part of something that contributed new information (the cannon study) to the understanding of an event was amazing. I also thoroughly enjoyed working on Chapter 5, which dealt with how the battlefield and sites changed over time. It was one of those times when my background in historic preservation was put to good use. I relished studying maps and then going out in the field and thinking about the probable locations of key sites on the island, where these events took place, and how the landscape had changed over time. Now, when I drive around the island I can’t help but think about General Sullivan’s army marching down East Main Road on their way to Honeyman Hill, or imagine the British occupying a seven-gun battery around the corner from my in-laws’ house. Even though I already valued historic sites and the history of Aquidneck Island, it’s given me new context and appreciation for landmarks I see every day.

Questions for Kenneth Walsh and His Answers

1. Tell our readers briefly about yourself and how you got interested in the Siege.

I am an engineer, a graduate of Northeastern University and the University of Rhode Island. I have a Professional Engineers License in Rhode Island and spent forty-three years working for the Naval Underwater Warfare Center in Newport. When I retired in 2002, I went back to school, receiving a PhD from Salve Regina University. The dissertation was on Newport history and economics.

My interest in the Siege all started at the Bicentennial back in 1976. A neighbor recommended that I read The Diary of Fredric Mackenzie, which contained a firsthand account of the Siege by a British officer. It had a map of Card’s Redoubt (Green End Fort) so I took it down to the redoubt on Vernon Avenue to see what the British saw when they looked across the valley at American lines.

I could not see what Mackenzie saw! Mackenzie had Green End road as it goes up Honeyman Hill to the right of the redoubt but it is to the left when viewed from the Vernon Avenue Redoubt. A check of the British maps at the Newport Historical Society, of which I was a member, supported Mackenzie. In fact, the redoubt on Vernon Avenue would have been directly in front of the British seven-gun battery, an unlikely situation. The British left Newport in 1779. The last map of the redoubt was French drawn in 1780 when Rochambeau was in Newport.

The French map showed the Vernon Avenue Redoubt as the Redoute de Saintonge, one of three new redoubts built by the colonial militia and their French allies to defend Newport in 1780 from possible attack by a British expeditionary force. An article was published by the Newport Historical Society that showed that based on the maps, the redoubt on Vernon Avenue was the Redoute de Saintonge with an error of less than 1:1000000.

2. Your work using British-made maps of the Siege and the British defenses is innovative and interesting work. Tell our readers about it. Where did you obtain the maps? What did you hope to accomplish by using the maps?

While there is a saying that “a picture is worth a thousand words,” a map is worth a lot more than that. A well done map can show where everything is located on a battlefield with very little ambiguity. When we started the project, maps were obtained from the Newport Historical Society and other local historical societies, libraries including the Redwood Library in Newport, and, most importantly, the William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan, where we obtained fifty-four maps and drawings. From the maps, we could tell where the cannons were and what kind of protection was provided to them. This was critical to the analysis because the General Sullivan’s plan was to advance down Aquidneck Island to Honeyman Hill and destroy the British defenses with cannon fire, and then attack with infantry across the valley where Green End Road crosses the north end of Eastons Pond. It was a good plan but it did not work and to find out why we used the map information, the details of the British forts, and some good engineering analysis.

Mackenzie reported that the “Rebel” cannon hit the British redoubts but did not penetrate them. When night came, the British troops would go out and patch up the redoubts.

An engineer from Roger Williams University, Drew Canfield, and I reviewed the analysis of smooth bore cannon and the aerodynamics of cannon balls in trans sonic flight. We developed the software to predict impact velocities for the elevations and distances indicated on the maps. There was some data on penetration of the ground by cannon balls produced by the French but it did not appear to be correct. Dr. Aaron Bradshaw of the University of Rhode Island developed the software to check the ground penetration based on work by Sandier Labs in New Mexico. There was anecdotal data that some of the cannon balls were spinning at muzzle exit. Dr. Stephen Jordan of the University of Rhode Island checked this and did a complete analysis, which is included in the report.

Without the maps and drawings, we would not have understood what had happened at the Siege.

3. Can you expand on the history of the name of the park called Green Fort in Middletown and why you believe it is really Redoute de Saintonge? I am aware you wrote an article on that topic many years ago for the Newport History journal. Why won’t the name of the park be changed to reflect the newly-uncovered information?

The history of misnaming the redoubt on Vernon Avenue started in 1924 when Dr. Roderick Terry, then president of the Newport Historical Society, identified it as a British fort. Mackenzie’s diary was not yet in circulation and many of the maps not so easily accessible, so there was very little documentation to suggest otherwise. It was assumed that all the forts in the area began as British forts and were later converted for use by the French and their American allies. In 1976, the first report suggesting a French origin was published in the Newport History journal but since Dr. Terry had been such an admired and trusted historian, any opposing theory was going to be going up against his reputation. It was during this time that the MHS was founded. Hopefully our current report will help to convince others that the French actually did build the redoubt on Vernon Avenue in 1780. The 240th anniversary of the building of the fort is coming up in 2020 and we would love to see some kind of signage to rectify and commemorate this.

Close up of a map by a French cartographer in 1780, showing French forts while the French occupied Newport and sought to build defenses in Middletown. At the top left, number 6 marks Redoute de Saintonge at what is now Vernon Avenue (Plan de la Ville, Rade …, Library of Congress)

4. You also have done some interesting work in the project on artillery used during the siege of Newport. Tell us about that. What were you trying to accomplish with this analysis? Where did you obtain the scientific background for your analysis?

General Sullivan’s artillery was the key factor in the success or failure of the Siege. To understand the Siege, it was necessary to understand the capabilities of the cannon. Computers are wonderful tools. The modern desk top computer combined with MATLAB, an engineering analysis software from The Math Works, can model complex engineering problems. It was used to model the American cannon in fine detail. The work by the Navy Lab provided a vast background in weapon analysis, which was augmented by a large volume of technical literature available in the technical journals and the internet.

5. Please talk about the archeological and ground radar work that was done.

The archeological and ground radar work was all preliminary. The Ground Penetrating Radar(GPR) surveys were done at the redoubt on Vernon Avenue, the Aaron Lopez farm on Wapping Road, and at Linden Park (formerly Fort Fanning). Dr. Jon Marcoux of Salve Regina University did the surveys. More work needs to be done.

6. Do you think Sullivan’s army, without the assistance of the French navy and army, could have succeeded in the Siege?

No. Sullivan had only 3,000 regular soldiers and that included the 2,000 sent by General George Washington from White Plains, New York. At the time of the Siege when an attack could have been executed, the militia enlistments were expired and many militiamen were going home. In any case the cannon in Sullivan’s army was not large enough to do the job of destroying the British forts.

7. Do you have any more plans to work in the areas of historic maps and colonial/revolutionary war artillery?

The events involving the French fleet in Rhode Island waters need to be examined in detail. Salvos from the large French warships did no significant damage to the British forts located where Fort Adams is, on Goat Island, and a few other places near Newport Harbor. That is unreasonable given the cannon size and the ranges. It needs to be looked at in detail.

Recent photo of Redoute de Saintonge on Vernon Avenue, which was misidentified as Green End Fort in the early 1900s (Kenneth Walsh)

Could the French fleet have successfully blockaded Newport, which combined with Sullivan’s troops would have forced a surrender and won the war? That is worth considering more.

The Aaron Lopez farm needs to be examined in detail. Lopez was the richest merchant in Newport in 1775 and he left in that year to get away from the British. He may have left things at the farm. The Lopez farm was used as a fortified house during the British occupation. It needs to be thoroughly checked.

[Banner image: Close up of a map by a French cartographer in 1780, showing French forts while the French occupied Newport and sought to build defenses in Middletown against a possible British invasion. At the top left, number 6 marks Redoute de Saintonge at what is now Vernon Avenue (Plan de la Ville, Rade …, Library of Congress)]]