In the evening of December 16, 1773, a band of Boston Whigs (commonly known today as Patriots) charged onto three merchant ships at a wharf in Boston Harbor and dumped overboard more than 46 tons of tea from 340 wooden chests.

Tea was the only import into North America that still had one of the Townshend duties attached. Parliament had repealed those tariffs on other goods in 1770 but kept the tea tax, which accounted for far more than half of the money collected under that law. Much of that revenue went to salaries of officials that the royal government appointed to administer America—customs officers, governors, judges. (Only in Rhode Island were both the governor and the judges still elected locally.) That meant the remaining tea tax constituted the most visible example of “taxation without representation.”

With its 1773 Tea Act, Parliament changed how tea was transported from India through Britain to North America. Previously, the British East India Company brought its main product to London, paying a tariff as it landed. The company then auctioned that tea off to merchants who shipped it to North America, sold it there, and paid the Townshend duty. With the East India Company in financial straits, Parliament’s new law was designed to help it make more money in two ways. First, the tariff the company paid on tea brought from India went down. Second, it was now allowed to ship its tea across the Atlantic and wholesale it in North America, bypassing middlemen.

Together those changes promised to lower the consumer cost of tea for North Americans. That, prime minister Lord North hoped, would make East India Company tea more appealing than tea smuggled in (with no tariffs) from Dutch territories. Furthermore, since the company would be responsible for paying the Townshend duty as soon as its cargos were unloaded in the colonies, collecting that tax would be easier and quicker for the imperial government.

The East India Company chose four ports in North America for its first shipments: Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston, South Carolina. The next largest port in the colonies was Newport, but it did not make the company’s list. Possibly planners thought that Boston would supply the whole New England market. Possibly men in London worried about disorder in Rhode Island after the attack on the Gaspee of 1772. For whatever reason, Rhode Islanders did not get the opportunity to protest the East India Company tea as “taxation without representation” by preventing it from being landed.

Nevertheless, some Rhode Islanders ended up playing a role in how Boston’s destruction of the tea was discussed in the press.

First, on December 18, 1773, less than two full days after the evening the tea was destroyed, the Providence Gazette published the first news story about that event:

By a Gentleman from Boston we learn,…on Thursday Evening the Populace assembled, and proceeded to the Long-Wharff, where they threw a great Quantity of the Tea overboard, destroyed what remained, and then dispersed. The Quantity shipped in these two Vessels was about 300 Chests.—This is the best Account we have yet been able to obtain of this very interesting Event.

This early report was not entirely accurate. The raid occurred at Griffin’s Wharf (not Long Wharf) and there were three vessels attacked (not two). Given how Americans picture that event today, however, the most striking gap in this report is the lack of detail about the people who carried out that action.

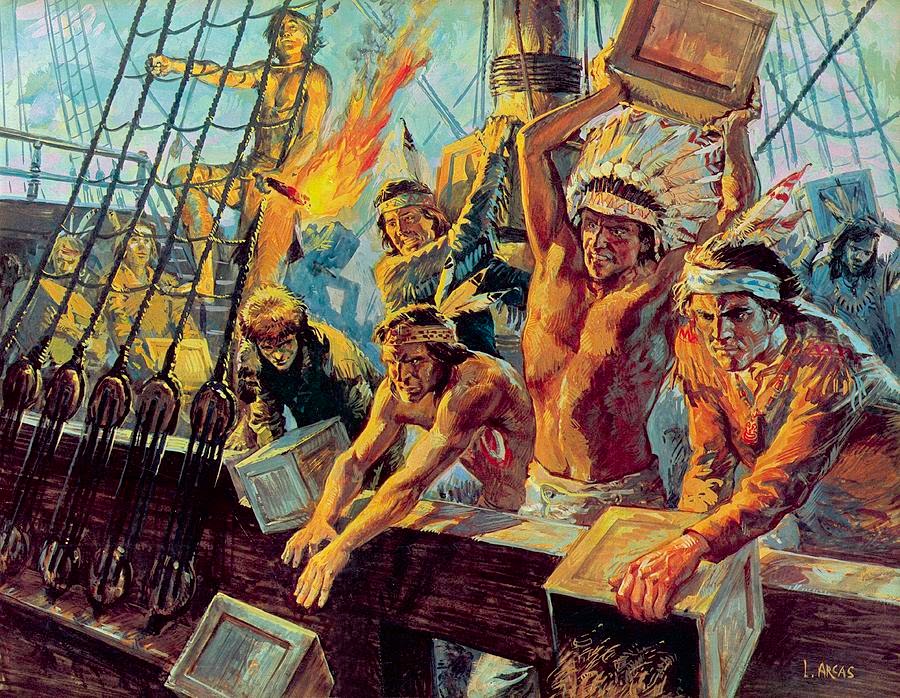

A woodcut from the late eighteenth century showing the scene at Griffin’s Wharf in the evening of December 16, 1773 (Yale Art Museum)

Already people in Boston were remarking on how some of those raiders had disguised themselves as Indians. The merchant John Rowe wrote in his diary, probably the next morning:

A Number of People appearing in Indian Dresses went on board the three Ships… they Opend the Hatches hoisted Out the Tea & flung it Overboard – … Tis said near two thousand People were present at this Affair.

Rowe himself was not in that large crowd of spectators, nor was another merchant, John Andrews, who shared secondhand information in a letter to his brother-in-law on December 18:

They say the actors were Indians from Narragansett. Whether they were or not, to a transient observer they appeared as such, being clothed in Blankets with the heads muffled, and copper colored countenances, being each arm’d with a hatchet or axe, and pair pistols, nor was their dialect different from what I conceive these geniuses to speak, as their jargon was unintelligible to all but themselves.

The Boston Gazette edition of December 20 had more details. According to “An Impartial Observer,” the attack occurred after a well-attended meeting at the Old South Meeting House:

Previous to the dissolution, a number of persons, supposed to be the Aboriginal Natives from their complexion, approaching near the door of the Assembly, gave the War Whoop, which was answered by a few in the galleries of the house where the assembly was convened; silence was commanded, and a prudent and peaceable deportment again enjoined: The Savages repaired to the ships which entertained the pestilential Teas, and had begun their ravage previous to the dissolution of the meeting.

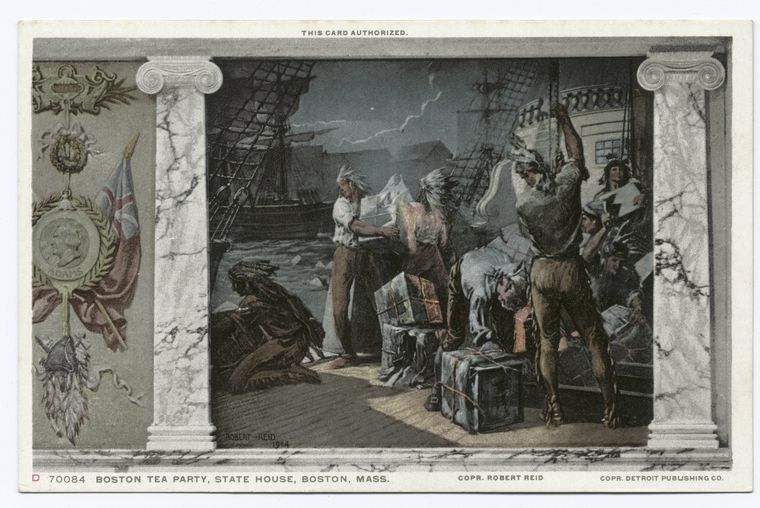

Postcard showing the Boston Tea Party painted on a mural at the Massachusetts State House in Boston (New York Public Library)

This narrative described the raiders as “Aboriginal Natives” and “Savages” but did not specify a specific tribe, as Andrews did.

That same day, the Boston Post-Boy newspaper linked the raiders to a different tribe. Those men were “dressed like Mohawks or Indians,” that pro-government newspaper said. Mohawks were members of a feared Indian tribe then located mostly on the upper Hudson River, not close to Boston. However, the name of that nation had acquired another meaning early in the century after a London street gang had adopted it for themselves. In his 1757 dictionary, Dr. Samuel Johnson thus defined “Mohock” to mean: “The name of a cruel nation of America given to ruffians who infested, or rather were imagined to infest, the streets of London.” More than other Indian nation names, therefore, “Mohawks” carried a connotation of criminality in Britain.

John Adams referred to yet another group of Indians when he discussed the tea rescued from a fourth ship, which accidentally ran aground on Cape Cod a few days later. On December 22, Adams wrote to his friend James Warren:

We are anxious for the Safety of the Cargo at Province Town. Are there no Vineyard, Mashpee, Metapoiset Indians, do you think who will take the Care of it, and protect it from Violence[?] I mean from the Hands of Tyrants and oppressors who want to do Violence with it, to the Laws and Constitution, to the present Age and to Posterity.

Adams wanted Whigs on Cape Cod to ensure that tea never came to market. But by writing of the people who would undertake such illegal action as “Vineyard, Mashpee, Metapoiset Indians,” he skirted the danger of advocating that his fellow colonists commit a crime.

People like Adams, Andrews, and the Boston newspaper writers had quickly realized that by referring to the men who destroyed the 340 chests of tea in Boston harbor as Indians, they could discuss and even praise that act without acknowledging any community responsibility for it. And of course, they could tell any royal authorities who asked that they could not possibly identify those “Indians”—some of whom were only lightly disguised while others had worn no disguises at all.

By early 1774, Bostonians appear to have reached a consensus that not only did “Indians” destroy the tea, but those “Indians” were Narragansett. Unlike the Mohawk in New York, that Rhode Island–based tribe was more plausibly within striking distance of Boston.

Thus, the Essex Journal, published in Newburyport, Massachusetts, in its January 5, 1774, edition wrote that “a number of Cape or Narragansett Indians” were responsible for destroying the East India Company tea.

In March, another ship arrived in Boston with tea. A report in the Boston Gazette concluded: “The SACHEMS must have a Talk upon this Matter—Upon THEM we depend to extricate us out of this fresh Difficulty…” That was a call to repeat the illegal action of December, just barely disguised through the reference to Indian leaders instead of locals.

Men did indeed destroy that tea, and the March 10th Massachusetts Spy described the action using this allegorical language:

His Majesty OKNOOKORTUNKOGOG King of the Narraganset Tribe of Indians, on receiving Information of the arrival of another Cargo of that Cursed Weed TEA, immediately Summoned his Council at the Great Swamp by the River Jordan, who did Advise and Consent to the immediate Destruction thereof. . . . They are now returned to Narragansett to make Report of their doings to his Majesty, who we hear is determined to honour them with commissions for the peace.

Exaggerated phrases like “commissions for the peace,” not to mention references to “the Great Swamp” and “river Jordan,” show that whoever wrote the article was not trying to convince readers that actual Narragansett Indians had dumped the tea in Boston harbor. It was all a joke, and the smart people were in on it.

Over in London, the tea merchants who lost that March cargo complained to Parliament about “a great Number of Persons all of whom were unknown to the Captain and many of them disguised and dressed and talking like Indians armed with Axes and Hatchets.” They clearly did not believe any of those persons were actually Indians. But the disguise concealed the raiders’ identity and let American Patriots talk about the destruction while denying knowledge of the people behind it. As for the Narragansett themselves, striving to hold onto their rights and land in southeastern New England, they were the Bostonians’ unwitting scapegoat.

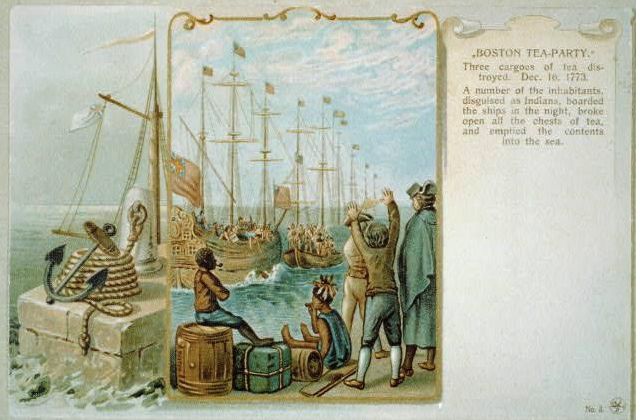

Modern depictions of the men of the original Tea Party with feathers in their hair, and full feathered headdresses and bare chests, as shown above, was taking the joke too far

Today many descriptions of the Boston Tea Party include the term “Mohawks” for the men who destroyed the tea, and none say “Narragansetts.” How did that change come about?

The seed might have been planted in the January 22, 1774, London Chronicle, which reported on the event by reprinting a paragraph from Boston Gazette but inserting in parentheses a phrase from the Boston Post-Boy: “dressed like Mohawks or Indians.” The term “Mohawks” was more meaningful for London readers than “Narragansetts,” and the London Chronicle and histories derived from it would carry authority.

Few early United States authors used the “Mohawks” term. Histories of the Revolution by the New England-based Reverend William Gordon (1788) and Mercy Warren (1805) did not include that word in discussing the destruction of Boston’s tea. Nor did the two 1830s books based on interviews with participant George R. T. Hewes, which popularized the name and memory of the “Tea Party” and played up the Indian disguises.

It looks like only in the last decades of the 1800s—a century after the event—did American authors start to use “Mohawk” (always in quotes) as a standard term for the men who had destroyed the tea at Boston. Yet in the same period and later, artists did not picture those men as Mohawks. Instead, illustrations increasingly showed the Tea Party made up of stereotypical Plains Indian warriors: bare-chested in a New England December, wearing not just a feather in their hair but full feathered headdresses. These figures were simply stereotypical Indians, and it no longer mattered if they lived close to Boston at all.