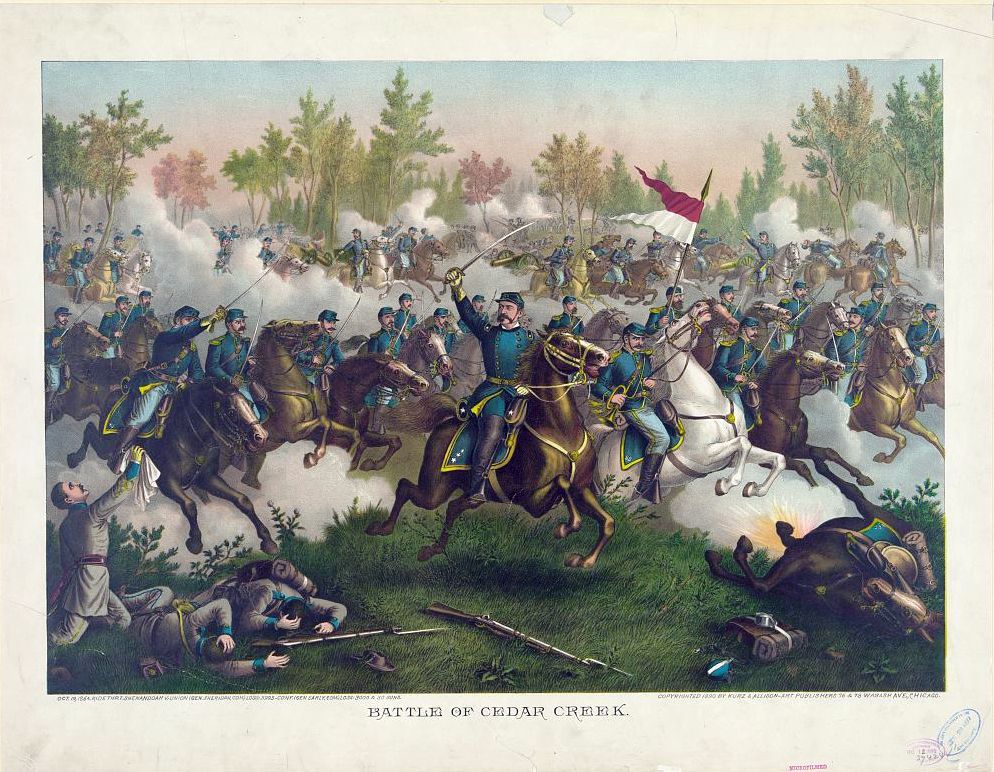

In the early morning hours of October 19, 1864 along the banks of Cedar Creek, just south of Middletown, Virginia, a large Confederate army under the command of General Jubal Early prepared to strike the sleeping Union forces. As the rebel yell and the crack of musketry filled the dawn air, thousands of Union soldiers ran for their lives. Into the mêlée rode Colonel Charles H. Tompkins of Providence. A thirty-year-old combat veteran of many bloody battles, and the commander of the First Rhode Island Light Artillery Regiment, Tompkins also led the Sixth Corps Artillery Brigade. As a brigade of Alabamians bore down in front of him, he quickly spotted Lieutenant Jacob Lamb and Captain George W. Adams, commanding Battery C and Battery G, First Rhode Island Light Artillery, respectively, and ordered them to hold their positions at all costs until reinforcements could arrive.

Tompkins dismounted from his horse to help Battery G get its guns in position, but was soon shot in the arm and went to the rear. Two of the prized Parrott rifles of Battery C had already fallen to the enemy. Lieutenant Lamb tried desperately to avoid the same fate for the other two guns. With nearly a third of his men down, he gave the order for double canister, which effectively turned the cannon into the world’s largest shotgun, to be fired at the enemy. A fellow soldier who saw the action recalled, “Lamb’s C 1st Rhode Island got into a hot place and was made the subject of a rough and tumble fight.” In an instant the Alabamians were mowed down into a pink mist in front of the bedazzled Rhode Islanders. Pulling their guns out of a slight depression, the men from the smallest state received a most welcome surprise as the Old Vermont Brigade arrived on the field and launched a desperate counterattack to save the cannons. The Rhode Islanders were finally safe, but across the field lay the carnage of combat and dozens of dead and wounded Rhode Islanders, Alabamians, and Vermonters. Among the Rhode Islanders who would never be seen again was James A. Matteson of Scituate.

The service and pension files contained within the National Archives contain some of the best records for the study of Rhode Island’s Civil War soldiers. Often filled with details of injuries and sickness, the struggle to obtain pensions after the war, as well as pertinent genealogical information, these records are a treasure. For genealogists they provide important information regarding family dynamics, where people moved after the war, and sometimes contain the actual letters of the soldiers themselves that family members sent to Washington, D.C. in a desperate attempt to get a pension after their loved one failed to return home. The documents are now being studied by scholars to reveal that the true figure of the loss of life in the Civil War was 750,000, much higher than previously thought.

The subject of this study, James A. Matteson (sometimes referred to as Maddison, Mathewson, or Mattison) in the army records was born on January 4, 1843, in Scituate, Rhode Island. He was the son of Rhoda and Henry Matteson, a small-time farmer. The Mattesons had seven children, all born between 1839 and 1856. James’s early life would have been uneventful, as he labored on his family’s small farm and attended classed in the winter. James’s life continued unabated until 1861, when like many other young men in the state, he felt the need to enlist to preserve the Union. He was seventeen years old at the time and the parental permission he needed to enlist was granted by Henry and Rhoda after he promised to send his entire pay home.

Even twenty years after the war, Rhoda remembered the last time she saw her son. He was six feet, two inches tall. She recalled, “His hair was dark brown and the color of his eyes was a dark hazel.” Matteson enlisted as a private in Battery C, First Rhode Island Light Artillery, on August 25, 1861. Unfortunately, none of his wartime letters are known to survive. Recruited from throughout the state, Battery C was composed largely of men from Providence, but also included smaller detachments from South County and the Pawtucket area. The unit went south in August 1861 and was assigned to the Washington, D.C. area.

After a winter of training, the battery, under the command of future Rhode Island historian Captain William B. Weeden, was assigned to the Fifth Corps of the Army of the Potomac. With the Fifth Corps, Battery C went on to see heavy combat on the Virginia Peninsula, where on June 27, 1862, they were overrun by a brigade of Texans. Several days later, five men were killed in a friendly fire incident at the Battle of Malvern Hill. The unit was also engaged at the major battles of Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville. In the late spring of 1863, Battery C was transferred to the Sixth Corps, and the men followed the corps to Gettysburg, but they were not heavily engaged in the ensuing battle. Further combat came in the spring of 1864 at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, Cold Harbor, and Petersburg. Transferred to the Shenandoah Valley in August 1864, the original members of the battery who had not reenlisted were sent home to muster out. Reduced to fewer than 90 men from an authorized strength of 150, the remaining soldiers fought at the Battle of Opequon on September 19, and three days later followed up the victory at Fisher’s Hill. Private James A. Matteson, remarkably, survived all these engagements unscathed until his luck ran out after General Jubal Early’s surprise attack at Cedar Creek on October 19, 1864.

At some point during the early morning mêlée for the guns, Private Matteson was shot in the head by an Alabama soldier. As his comrades ran for their lives, they had no choice but to abandon Matteson and other wounded comrades as they rushed to try to save their cannon and reform a line to stop the Confederate assault. The Confederates captured several wounded Rhode Island soldiers, but Private Matteson was not among them. To complicate matters, soon after the battle, Battery C and Battery G were consolidated into a single unit, called Battery G. On the final muster roll of Battery C, Matteson is listed as “Absent in Hospital Wounded.” He continued to be listed as wounded, in the hospital until the final muster out roll of Battery G, dated June 24, 1865, when the following report was made of him: “Was in hospital of Artillery Brigade 6th A.C. at the battle of Cedar Creek Va, October 19, 1865 with fractured cranial. Investigation fails to elicit further information.” Although carried on the muster rolls as being in the hospital wounded, it was clear that no one in either Battery C or Battery G ever saw James A. Matteson alive again.

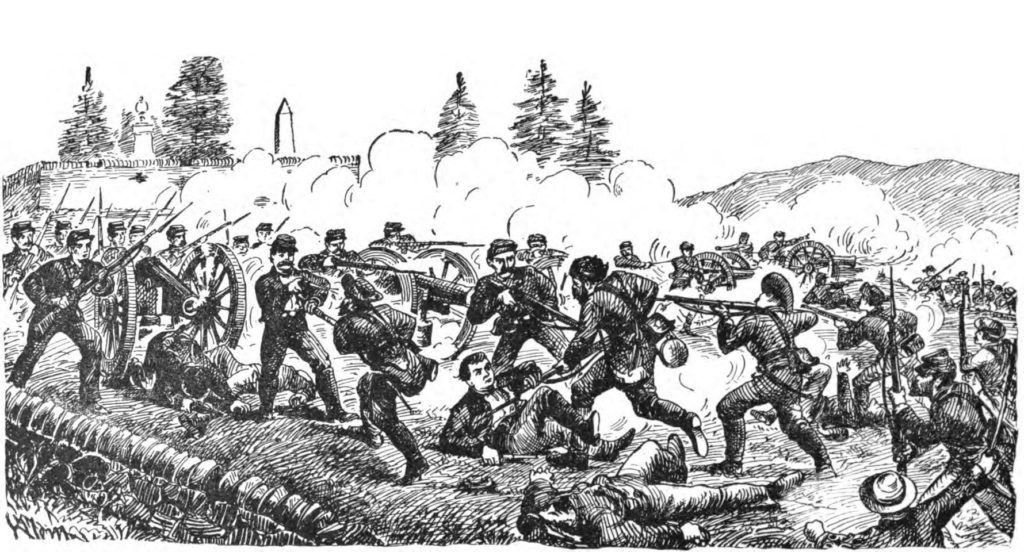

This print shows part of the fierce action between Lamb’s Battery C, the Vermont Brigade, and some Alabamians at Cedar Creek (Buell, The Cannoneer)

Back in Scituate the tragic news arrived: Private Matteson was missing in action and presumed dead. In December 1863, Matteson had reenlisted as a veteran volunteer, earning a five hundred dollar bonus, and a thirty-day furlough home. The money, along with any back pay, would have been sent to the family in Scituate. It is clear from the army records that James sent the majority of his pay home to his mother, and that his death represented a significant loss of income to the family.

Henry Matteson, James’s father, owned about seventy acres in Scituate. The farm was valued at $600 in 1864, but by 1878, as the population of Scituate began to expand, and land values soared, the property was now valued at $1,200, placing a severe tax burden on the struggling family as they became older and tried to maintain the farm. Faced with losing the farm, in 1878 Henry borrowed $200 from a neighbor, mortgaging a portion of the farm. Needing help to support herself, Rhoda filed for a federal mother’s pension on August 22, 1879. Under acts of Congress from 1862 and 1873, parents who were dependent upon their children for support, and whose children died as a result of their war service, could seek a pension. Little did Rhoda know then of the difficulty she would have in obtaining a pension.

Rhoda, as evidenced by her pension filings, could not write her name and left her “X” mark on her surviving documents. On August 6, 1879, at age fifty-nine, she appeared before the Kent County Clerk of Court, Thomas M. Holden, and filed her pension. She declared that her son was James A. Matteson and that he “died at Middletown, Va from wounds on the 19 day of Oct 1864.” She also swore that she had been dependent upon her son for support, and that her husband Henry “is unable to fully support me on account of ill health.” Two neighbors attested to these facts. Rhoda appointed N.W. Fitzgerald, a pension agent from Washington, D.C., to represent her. She filled out the pension documents and sent them to Washington, hoping to receive the meager funds a pension would bring her.

Rhoda’s pension application was given claim number 250,167. Much as today, the government moved slowly on her application, and it took nearly two years for it to be reviewed by a Pension Bureau clerk. On September 28, 1881, the War Department responded to a Pension Bureau request for information about James’s death. It responded that he “Died October 19, 1864 at Middletown, Va from wounds as claimant states.” The War Department stated that the information came from the muster rolls of Batteries C and G in its possession. Nominally, the statement from the War Department would be acceptable as final proof of a soldier’s fate, but in the case of James Matteson, this would not be the case. The clerk from the Pension Bureau needed Rhoda to prove both that her son actually died as a result of the combat at Cedar Creek and that she was indigent as she stated on her declaration.

Another inquiry to the War Department brought about a letter from Lieutenant Colonel Joseph J. Woodward that “James Maddison Priv. Co. C 1 R.I. Arty received a fracture of cranial bone at the battle of Middletown, Va Oct. 19, 1864.” Like the War Department, Woodward based his report on the “records of Battery C.” A further inquiry revealed that Matteson had not been treated at a general hospital at Winchester, Virginia, Frederick, Maryland, or in Washington, D.C. Instead, it appeared that Matteson had simply disappeared. In 1866, the government had removed many of the remains of Union soldiers who died in the northern Shenandoah Valley to the new Winchester National Cemetery; among them were a dozen Rhode Islanders. The body of James Matteson was never identified. He was likely buried in an unmarked grave, presumably in the Winchester National Cemetery.

While every indicator stated that Matteson had died shortly after being wounded at Cedar Creek, the Pension Bureau continued to press for further information, along the lines that Matteson had not been mortally wounded at Cedar Creek and instead had made it to a general hospital for treatment. A clerk wrote, “It is stated the soldier was placed in an ambulance the morning after the battle and carried to Winchester, Va and in a day or two was taken to a hospital in Winchester, Va and died.” With much on the line, Rhoda began the painstaking process of gathering additional affidavits of support to help her case.

On February 28, 1883, Andrew Burns and Charles McCarthy, two veterans who had served in Battery C with Matteson submitted an affidavit to the Pension Bureau in support of Rhoda. They stated:

Matteson was wounded in the head in said action while in line of duty. He was thereby totally disabled, and fell into hands of the enemy. Later in the day our forces regained the field and Matteson was retaken by us. Both saw him after he was retaken, and saw that he was badly wounded in the head in two places. They never saw him afterwards. They heard the wounds spoken of so being fatal, and understood afterward that he was taken to some hospital and they subsequently heard the next day they think that he died of his wounds.

As stated by his comrades, Matteson died in a field hospital the day after he was wounded. With the horrible conditions facing the surgeons after the battle, they did not have time to keep accurate records, but instead worked long hours to try and save as many patients as possible. Matteson did not make it to a larger hospital, but rather was treated in the Artillery Brigade of the Sixth Corps field hospital on the field at Cedar Creek.

The clerk at the Pension Bureau nonetheless was skeptical about the testimony of Burns and McCarthy. He was concerned that Matteson was still alive or had not died from the battle, and that the family was involved in a conspiracy to obtain a pension under false pretenses. The suspicious clerk wrote to the War Department for information to confirm that Burns and McCarthy had been present with Battery C at Cedar Creek. This claim was confirmed.

While his comrades rallied to support Rhoda, she submitted her own statement that she remembered a physical description of her son, and added “I have never seen him since his re-enlistment on or about 1863, that I have been informed that he was wounded in battle and died at Hospital and I have never seen or heard of him since.” When pressed to provide correspondence James had sent home, she replied, “I further testify that few letters were received from the soldier and so far as I know they have all been destroyed or lost. Several other neighbors responded and wrote, “We knew of the enlistment of James A. Matteson and of his reported death and that we have never seen or heard of him since October 1864 and that we were informed that he was wounded in battle and died from the effects of his wounds.” These affidavits appear to have been the tipping point, as Rhoda was finally able to prove that her son died in the Civil War.

Having filed her original claim in 1879, by 1883 she was desperate for support. While she proved that her son died in the war, Rhoda still had an equally challenging time providing that she was indigent. She wrote in a plea to the government for support:

My husband is of feeble health and unable to support himself and me and we are both so feeble and old that we must suffer if we cannot get help from some source and as our son gave his life for his country, we are now in our old age left without his help and care. We have no letters written by him whilst in the service they have all been destroyed, our property is mortgaged and our income is not sufficient to support us. Our son before he enlisted gave us his entire wages and he sent us what money he could up to his death.

Because she did not have any of her son’s letters to show that he had sent cash home, and she was still married, Rhoda found it very difficult to establish that she needed her mother’s pension. Ill with tuberculosis since 1864, Henry Matteson was nearly totally disabled, and unable to farm and complete “hard labor.” His taxes continued to increase, and his sister gave him some abutting property to help support the family, but the income from this was bringing in about $125 per year in 1875, hardly enough to support the family. When asked to provide even more evidence of her financial condition, Rhoda submitted yet another heart-wrenching plea for support. She wrote, “There has been no person legally bound to support her and that she has been supported by her children and her neighbors. Her husband is sick and has not been able to do anything during the winter past and that the probability is that he will not be able to do anything for a long time if ever.” Rhoda feared that she would be forced to sell off all of her property and seek relief from the town farm in Scituate for indigents for support if she did not receive a pension.

Although Henry had sought medical treatment, it did little to relieve his tuberculosis, an almost certain death sentence in rural Rhode Island at the time. The Pension Bureau wrote yet another letter to Rhoda, asking her for proof from her neighbors that Henry was disabled and unable to provide for her. In a letter dated July 1, 1883, an acting commissioner wrote, “The evidence filed showing the husband’s ability to provide for claimant is too indefinite. If no medical evidence is obtainable, then the testimony of neighbors will be considered if the nature and extent of disability is shown, also when, by where, and for what any medical treatment had been rendered between 1863 and 1875.” Furthermore, they wanted to know the extent of Henry’s property and the value of his crops.

Additional neighbors came to Rhoda’s support. Neighbors Henry Jackman and Orlando Salisbury wrote, “We know that he is a very feeble man as to bodily health being unable to perform any hard manual labor and unable to support himself and family and that he and his wife are not possessed of sufficient property to support themselves comfortably.” The pension agents seemed concerned that Henry Matteson owned a decent amount of land. Amasa Colvin and Harly Phillips, neighbors for over twenty years wrote, “The income from his real estate is small, he being unable to properly improve it on account of his feeble health, and not possessed of sufficient means to have it done, averaging about ten bushels of corn a year, and forty bushels of potatoes, besides a small garden.”

While Rhoda and Henry had several children, one neighbor noted that their children did not support their parents and that the elderly couple had to rely on credit at local stores, as well as the generosity of neighbors. While he owned nearly seventy acres of land, only three acres were farmable. When able to work, Henry’s farming brought in only about $50 per year. Many of their bills went unpaid, and they did not have much physical property. None of the affiants wrote about how the death of James affected the family, rather it was the loss of the income he provided his mother, and how his absence affected her ability to live by not providing the family with an income that he had previously earned as a farmer and a soldier.

Rhoda was fortunate to have Dr. Albert Sprague of Warwick come forward to provide an affidavit. Dr. Sprague served in the Civil War as the assistant surgeon of the Seventh Rhode Island Regiment. He wrote, “I am acquainted with the said Henry Matteson, that I have treated him at various times for the last seven years for pneumonia, incapacitating him from labor for long periods, and that he is now partially disabled.”

After a six-year battle to prove that her son died serving his country in the Civil War, and that she was indigent, Rhoda was finally approved for her mother’s pension on December 12, 1885. Perhaps as a consolation from the government that her son had died to save, she received a one-time payment of $2,152, which represented $8 per month from October 1864 through March 1886. For all the years of service, she paid her pension agent George E. Lemore $25 for his assistance. Beginning on April 2, 1886, a check for $12 per month was mailed directly to the Hope Post Office, in Scituate. Rhoda continued to receive her pension of $12 per month until June 4, 1893, when she was unceremoniously “Dropped from the Rolls: Pensioner Dead.”

Why did it take Rhoda Matteson six years to obtain a pension? In one of the cruel twists of history, there happened to be two men named James Matteson who were shot at Cedar Creek and both came from Rhode Island!

The subject of this article, Private James A. Matteson, was the son of Henry and Rhoda Matteson. A farmer from Scituate, he served in Battery C, First Rhode Island Light Artillery. This Private James Matteson, as evidenced above, was shot in the head at Cedar Creek, and died on October 20, 1864, at the hospital of the Sixth Corps Artillery Brigade. His body was never identified, and likely he rests in an unmarked grave at Winchester National Cemetery.

The other Private James Matteson (sometimes spelled Mathewson) who served in Battery G, First Rhode Island Light Artillery. This soldier was born on September 13, 1844, in North Kingstown. He was the son of Verbadus and Mary Ann Greene Matteson. His half-brother, Nicholas Whitford Mattewson (he spelled his name Mathewson, rather than Matteson) and full brother Calvin Rhodes Matteson served in the Seventh Rhode Island Regiment. Nicholas was killed in action at Fredericksburg on December 13, 1862. Calvin was wounded there and was discharged. He later reenlisted and drowned in December 1864 when the steamer North America sank off of Cape Hatteras carrying him home from the war.

The James Matteson of Battery G was also a farmer; he enlisted on November 12, 1861. At the time he was living in Coventry, which confuses the situation even more, as it is near Scituate. He too was wounded at Cedar Creek and was sent to the general hospital, which confused the Pension Bureau clerk into thinking it was James A. Matteson who had been sent there. The James Matteson of Coventry survived his wounds and returned to North Kingstown, where he married Hannah Hazard. He died on December 13, 1905 and is buried in Elm Grove Cemetery.

It is not surprising that given the nature of his death, Private James A. Matteson of Scituate, like many Rhode Islanders who died in the war, was not listed among his fallen comrades on the 1871 Soldiers and Sailors Monument in Providence. In the late 1880s, Rhode Island began to review the Civil War records, attempting to correct the abysmal reporting system that had been in place during the Civil War. In the 1893 Revised Register of Rhode Island Volunteers, the following listing was made for this soldier:

Battery C, First Rhode Island Light Artillery

Mattison, James A., Priv. Res., Scituate, R.I.; Aug. 25, 1861, enrolled; Aug. 25, 1861, mustered in; Dec. 21, 1863, discharged, by reason of reenlistment; Dec. 22, 1863, re-enlisted as Vet. Vol. Granted furlough of thirty-five days from Dec. 25, 1863; Oct. 19, 1864, wounded in the battle of Cedar Creek, Va and sent to the hospital of the Art. Brig, 6th Army Corps. Investigation fails to elicit further information.

Perhaps General William Tecumseh Sherman said it best when he stated, “I think I understand what military fame is; to be killed on the field of battle and have your name misspelled in the newspapers.”

In 1913, fifty years after the war, Scituate finally dedicated the Owen Soldier’s Monument as a memorial to “the loyal men of Scituate, 1861—1865, who Died in the Service.” Scituate had lost many of her sons serving in the First Rhode Island Light Artillery, and it was only appropriate that the monument was an artilleryman, inscribed with the names of the Scituate men who died in the Civil War. Although not listed on the monument in Providence, it was clear from the testimony of his neighbors in Rhoda’s pension application that James A. Matteson died in the Civil War and that he had lived his entire life before the war in Scituate. Although he was a soldier from Scituate, his native town neglected him as well, and his name was not recorded on the monument.

Private James A. Matteson rests in an unknown grave in Virginia. His name does not appear on any monument, and except for his pension file, his story would be lost to history. Although he never came home, perhaps the inscription carved on the Owen Soldier’s Monument in Scituate to the other men of the town who died “so that nation might live” in the Rebellion is a fitting epitaph for Private James A. Mattison of Battery C, First Rhode Island Light Artillery.

Rest Soldier, in thine honored grave,

Thy duty nobly done;

Long as thy Country’s banners wave,

The land whose life thou diedst to save,

Shall bless the memory of the brave

And prize her patriot sons.

Bibliography:

For information about the life of James A. Matteson, his Service and Pension File at the National Archives at Washington, D.C., contains all of the relevant information regarding his service, as well as his mother’s quest to gain a pension.

Information on the role of Battery C at Cedar Creek is taken from John R. Bartlett, Memoirs of Rhode Island Officers who were engaged in the service of their Country during the Great Rebellion of the South (Providence: S.S. Rider & Brother, 1867). In addition, Augustus C. Buell, The Cannoneer, Recollections of Service in the Army of the Potomac (Washington, D.C.: National Tribune, 1890), provided invaluable information as well.

In addition, the vital records of Coventry, Scituate, and North Kingstown, contained in the town clerk’s offices in those towns, provided birth, marriage, and death records that supported the information contained in the pension files.

The campaign history of Battery C, First Rhode Island Light Artillery is drawn from Edwin Winchester Stone, Rhode Island in the Rebellion (Providence: G.H. Whitney, 1865). This book consists of letters Stone wrote to the Providence Journal about his service in Battery C. In addition, Stone wrote a history of the unit for the Revised Register of Rhode Island Volunteers.

For details regarding the individual records of Rhode Island Civil War veterans, see Elisha Dyer, Annual Report of the Adjutant General of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations for the Year 1865, Cor., Rev., and Republished (Providence: E.L. Freeman & Son, 1893).

On the Civil War monuments in Rhode Island, refer to Gideon A. Burgess, Dedication Services: Owen Soldier’s Monument (Scituate: E.F. Sibley, 1913).

On the health of rural Rhode Islanders and the illness that Henry Matteson suffered from, refer to Michael Bell, Food for the Dead: On the Trail of New England’s Vampires (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2011).