On the night of June 17, 1863, a small group of men galloped for their lives out of Middleburg, Virginia. Tired, out of ammunition, and surrounded deep behind enemy lines, they followed their colonel who spoke broken English with a thick French accent. The men also spoke distinctively as well, with a Yankee twang unique to their southern New England home. They were the horse soldiers of the First Rhode Island Cavalry. Now they fought for their lives in a hostile country. As a result of their leader following orders to the letter, in a short time nearly the entire regiment would surrender in one of the decisive cavalry battles on the road to the Battle of Gettysburg that raged in early July.

Regarded as one of the finest fighting cavalry regiments in the Army of the Potomac, the First Rhode Island had already had a distinguished career before the Gettysburg Campaign. The regiment was activated under President Abraham Lincoln’s second call for troops in the fall of 1861. Rhode Island Governor William Sprague had come up with a unique idea that he presented to the governors of the other New England states. Instead of each state raising its own cavalry regiment, the six states that comprised New England would each contribute one two-company squadron to a unified regiment to be designated as the First New England Cavalry. The governors supported the idea, and returned to their states to begin recruiting. There was a problem, however, from the start. Before the raising of the new cavalry regiment, only infantry and artillery units had been raised in New England. Now, men flocked to the recruiting stations. Connecticut, Maine, Vermont, and Connecticut each had enough men to raise their own cavalry regiments.

Instead of two companies of Rhode Islanders, enough showed up to raise two battalions. Unique among the First Cavalry as a Rhode Island unit was that the companies were not raised geographically, rather the men were assigned to companies as they enlisted. Low on manpower after raising seven infantry regiments, New Hampshire could only raise a single battalion. The plan was now to unite the two Rhode Island battalions and the New Hampshiremen into the First New England Cavalry, the regimental flag bearing the symbols of both states.[1]

During the Civil War, the cavalry comprised a unique regimental structure. Consisting of twelve companies, or as they were called in the cavalry, troops. The regiment was divided into three battalions, each commanded by a major and designed to act independently. Each battalion was further broken down into two squadrons, of two troops each, commanded by a senior captain. The First New England was originally commanded by one of the few West Point graduates from Rhode Island, Robert B. Lawton. As the men left for Washington in March 1862, they received Morgan horses from Vermont, and were armed with Burnside carbines made in Bristol, Rhode Island. After arriving in Washington, the New Hampshire soldiers were aghast to learn that the name of the regiment no longer reflected the bipartisan efforts made by both states. Now the New Hampshiremen was designated as the Third Battalion of the First Rhode Island Cavalry.[2]

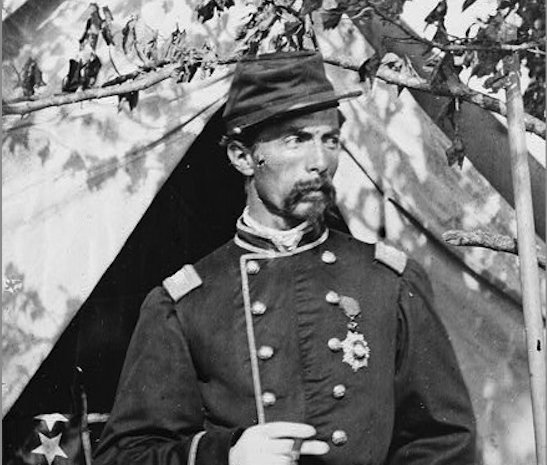

After some rudimentary training, the regiment was deployed into the Shenandoah Valley in the summer of 1862, fighting hard at Front Royal and Cedar Mountain, earning the respect of their superiors. Colonel Lawton resigned on July 1, 1862, and rather than promote the lieutenant colonel, Governor Sprague decided on a fateful course of action. He decided to pick a relatively unknown French officer, then serving as a major in the Second New York Cavalry: Alfred Napoleon Duffie.[3]

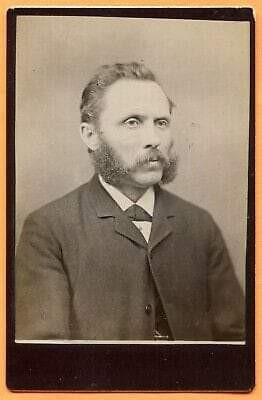

Duffie (pronounced Doof-yee) came highly recommended to Sprague. He was fond to tell others that he had been born to wealth in Paris and that he attended the St. Cyr military academy, and had fought in the Crimea War and in Senegal as a lieutenant of cavalry, earning four commendations for bravery and suffering wounds eight times. Constantly ill from asthma, Duffie said he came to New York City in 1860 to find a cure for the disease. In April 1861, he watched in awe as New York regiments left for the front. Unable to speak any English, Duffie found a fellow Frenchmen who explained the causes of the war to him. He also told him that French officers would not be allowed to serve in the America armies. Duffie said he was inspired by the memory of Lafayette to resign his commission and join the Union cause. He locked himself in a room for several months, determined to learn English.[4]

While he was an excellent fighter, unfortunately for Duffie, he came from a tarnished background and he exceedingly stretched the truth. His birth name was Napoleon Alexandre Duffie. The son of a beet sugar refiner, he enlisted in the French army at age seventeen and quickly received promotions to sergeant. He saw service in Africa, and was active in the Crimea, receiving several commendations for heroism. He was commissioned in 1859, but never went to a military academy.

Two months after he was commissioned, Duffie attempted to resign, as he had fallen in love with an American nurse in France. His request to resign was denied, so he deserted and fled to New York, where he eventually married into a rich and successful New York abolitionist family. He was stripped of his medals, and sentenced to five years in prison, but never returned to France. While he had won several medals for heroism in the Crimea, he was never wounded, and adopted the name Alfred upon arriving in America. He was well connected in the New York social circles, and quickly won promotion through his battlefield exploits in the Union Army.[5]

After several months of teaching himself English, Duffie could be understood and was commissioned into the Second New York Cavalry as a captain. Gaining a good reputation for his ability to train and lead troops, he was commissioned into the First Rhode Island Cavalry in the summer of 1862.

The Rhode Islanders detested the idea of having a foreigner command them, Nearly all the officers threatened to resign their commission, while the men almost mutinied. Duffie said he would resign in one month if he did not win their affection.

In a short time, Duffie transformed the First Rhode Island Cavalry. He instituted constant drills, acquired new uniforms and horses, stopped drunkenness and gambling, and sent the incompetent officers home. The men gave Duffie a nom-de-guerre that stuck: “Nattie,” for his well-kept looks. In a sign of affection towards their new colonel, the officers adopted a short blue jacket, heavily trimmed in gold braid, similar to that worn by French cavalry officers.

Although he did much to turn the regiment around, the men always had a difficult time understanding their leader. An officer recorded a conversation with Duffie pertaining to a New York regiment whose men spoke nearly two dozen languages. “The colonel of the Fourth New York, he gives an order, all the officer they stick up their head, they holler like one geese.” Although he could not always give the proper pronunciation, Duffie’s message was always clear.[6]

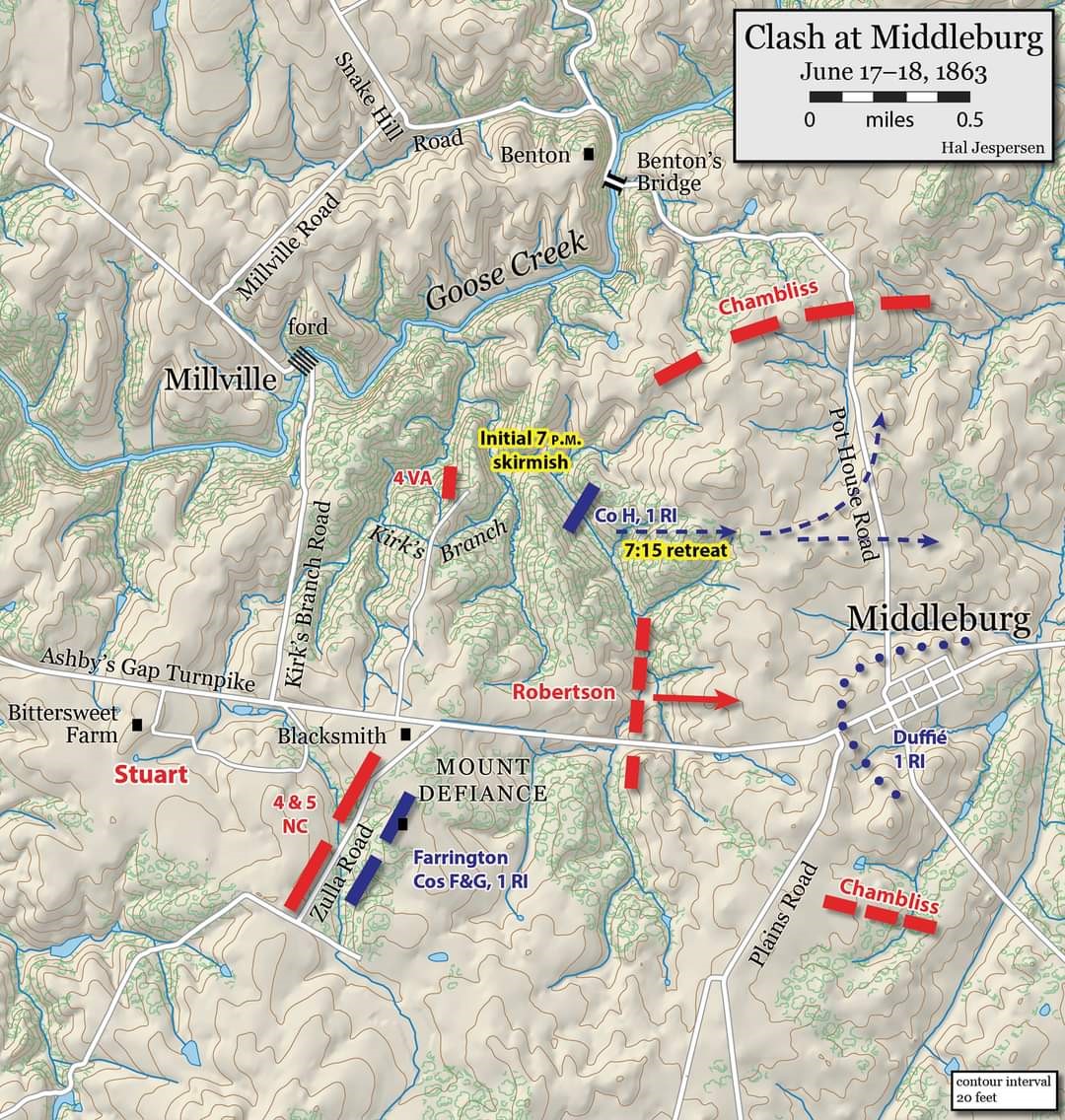

The men who composed Duffie’s regiment were some of the best that Rhode Island and New Hampshire had to offer. The majority of the officers were of patrician stock and were accomplished horsemen. Among them was Captain George N. Bliss of Tiverton, Rhode Island, who gave up a promising law career to join the regiment. Dr. Augustine Mann was a recent medical student who completed his studies by serving as an assistant surgeon. Typical of the enlisted men was John J. Spencer, a native Rhode Islander, and a farmer from East Greenwich who served in Troop H and John Sheridan of Providence, a recent Irish immigrant.[7]

Fighting at Second Manassas, the Rhode Island regiment showed that it have transformed itself from a demoralized, broken regiment, into one that was ready for combat. Held in reserve at Antietam and Fredericksburg, the First Rhode Island performed vidette duty along the Rappahannock in the winter of 1863. When Joseph Hooker was promoted to command of the Army of the Potomac, he took note of Duffie’s abilities and promoted him to brigade command. The New Hampshire soldiers were pleased that their major, John L. Thompson, became the lieutenant colonel and took command of the regiment.[8]

The Rhode Islanders continued on picket duty until March 17, 1863, when they participated in the Battle of Kelly’s Ford. The first Union soldiers to cross the Rappahannock, the Rhode Islanders drew their sabers and charged headlong into the Virginia cavalry, scattering them from the field. Although they sustained the heaviest casualties that day, the First proved that Duffie’s training regimen had worked. Hooker considered it one of the best cavalry regiments in the Army of the Potomac.[9]

With Hooker still in command, the First again fought at Brandy Station on June 9, 1863, where Duffie acted as a division commander. As with many officers promoted to higher command, Duffie did not measure up to command of a division at the time. During the reorganization of the Cavalry Corps in the days after the battle, Major General Alfred Pleasonton began a purge of the foreign born officers from his corps. As such, Duffie was demoted back down to command of the First Rhode Island Cavalry. At this time, the First Rhode Island was assigned to the Second Brigade (Kilpatrick’s), Second Division (David M. Gregg’s) of the Cavalry Corps, Army of the Potomac. The months of active campaigning had taken a heavy toll on the regiment. The horses were broken down and tired, while only 300 men remained present for duty.[10]

After it was discovered that the Army of Northern Virginia was on the move towards the Shenandoah Valley by way of the Blue Ridge Gaps after the Battle of Brandy Station, Hooker dispatched his cavalry into the Loudoun Valley in an attempt to find the Rebel forces. The infantry followed in close pursuit. Colonel Duffie and his troopers were assigned to patrol near Aldie, Middleburg, and Upperville, all locations where it was believed Major General J. E. B. Stuart and his division were lurking.

On the morning of June 17, Brigadier General H. Judson Kilpatrick gave Duffie the fatal orders:

You will proceed with your regiment from Manassas Junction, by way of Thoroughfare Gap, to Middleburg. On your arrival at that place, you will at once communicate with the headquarters of the Second Cavalry Brigade, and camp for the night. From Middleburg you will proceed to Union; thence by the way of Snickersville to Percyville [Purcellville]; from Percyville to Wheatland; then passing through Waterford to Noland’s Ferry, where you will join your brigade.[11]

These simple directions would have dreadful consequences for the First Rhode Island Cavalry. Duffie hoped that the mission would bring glory to him and his regiment, but privately confided in Lieutenant Colonel John Thompson that he saw the orders as “an effort to get rid of him by having his regiment captured or lost.” Thompson recognized that Duffie was a “thorn in the side of the higher officers.” Despite his belief that the orders would lead to the destruction of his regiment, or his dismissal from the service if he did not execute them, Duffie chose to follow them—to the letter.[12]

The First rode west from Centreville to undertake its mission. Major Preston M. Farrington rode alongside Duffie as the Frenchman talked constantly about religion, “a subject which he never had mentioned before.”

Riding into Thoroughfare Gap around 9:30 on the morning of the seventeenth, Duffie dispatched Troop H as skirmishers where they encountered nearly 600 dismounted Confederate troopers. The Rhode Islanders were “somewhat delayed,” in a small skirmish at the gap, but by 11:00, they had turned north towards Middleburg. During the brief engagement, three horses were killed, and several injured, but the regiment pushed on.[13]

Riding near Duffie, Lieutenant Colonel Thompson noticed that the colonel’s “anxiety increased,” as he realized that his regiment had no support. Duffie was “very uneasy,” but would not turn back from what he considered an important mission.

The Ninth Virginia Cavalry followed the First Rhode Island from a distance. Lieutenant George William Beale of the Ninth recalled, “We followed them, quite ignorant of their numbers, and how soon they might turn to attack us.” Beale had little to worry about, as there were ample Confederate forces in the area. The Rhode Islanders were now alone, deep behind enemy lines.[14]

At 4:00 that afternoon, the First Rhode Island galloped into Middleburg, described by one Confederate as “a pleasant little place, of some 1500 inhabitants.” Major Heros von Borcke recalled, “While paying one of the many visits I had to make and relating my adventures to a circle of pretty young ladies, the streets suddenly resounded with the cry of “The Yankees are coming!” Von Borcke and the famous J.E.B. Stuart were soon “riding off as fast as their steeds could carry them.” The Rhode Islanders nearly captured General Stuart and his staff. At the least, the Confederates “were compelled to make a retreat more rapid than was consistent with dignity and comfort.” After realizing that the Rhode Islanders were not pursuing, Stuart moved towards Rector’s Cross Roads, some eight miles away, and located the brigade of General Beverly Robertson. Stuart ordered Robinson to advance at once back towards Middleburg “and drive the enemy from the town without delay.”[15]

Theodore S. Garnett, an aide-de-camp on Stuart’s staff, later recalled the moment the Rhode Islanders appeared:

We were all quietly lounging around on the green grass under the shade of some fine old trees in the village- when all at once we were roused with the unpleasant intelligence that the enemy were within a half mile of the place, coming on the Thoroughfare Gap Road- a direction from which we least expected. There was but one thing to be done, namely, to mount our horses and leave town.[16]

From several captured prisoners, Duffie learned that he was surrounded by several of Stuart’s brigades. His orders were to camp at Middleburg, and so he proceeded to set up camp for the night.[17]

Barricading every entrance into the village, Duffie sent scouting parties out in every direction, while his men nervously waited. They knew that Stuart would soon return and that battle was imminent. Each trooper carried only forty rounds of ammunition for his carbine, which was a mixture of Burnsides and Sharps, depending on the troop. Captain Bliss recalled, “Ours was a desperate position to hold; but our orders were to hold it.”

Normally during dismounted operation one man in every four would hold the horses of his three comrades, thus reducing the fighting strength of a unit by a quarter. Colonel Duffie ordered all of the men to tie their horses to trees as he prepared to defend Middleburg with roughly 280 Rhode Islanders and New Hampshiremen. As the men prepared for action, Major Farrington and Lieutenant Colonel Thompson quietly ate a meal of milk and hardtack. Thompson realized the hopelessness of the situation, and thought he was eating his last supper on earth.

Major General Stuart, now recovered from the flight out of Middleburg, began to consolidate his scattered forces and prepared to retake the town. Major Heros von Borcke knew the countryside from his frequent rides through the area and led Robertson’s Brigade back to Middleburg.[18]

Duffie dispatched Captain Frank Allen and two men to Aldie, some five miles away to inform General Kilpatrick that the Rhode Islanders were cut off and surrounded. One of those chosen for the hazardous mission was Charles O. Green of Troop M for a very interesting reason Green recalled, “My blue jacket got very ragged and I availed myself of an opportunity to replenish my wardrobe, by confiscating a new gray knot jacket, which outwardly gave me the appearance of being a very respectable Rebel.” Instead of traveling on roads, Allen and his two companions traveled cross country, through the woods. At dusk they came across a small party of Confederates. With revolvers in hand, the enemy could not tell the Rhode Islanders as being Union soldiers. Captain Allen asked where Stuart’s men were, and was told they were heading towards Middleburg, at which point, the threesome carried on. A little down the road, they again encountered Confederates, and with a fake southern accent, claiming to be members of the Second Virginia Cavalry, again avoided escape. After a long, circuitous ride, Captain Allen and his men finally arrived at Union headquarters.

Private Green, after exchanging his gray jacket with one of Union blue, discovered many officers at headquarters drunk on whiskey and cider. At 9:00 that night, Captain Allen went to General Kilpatrick and told him that Duffie and his men were surrounded and needed reinforcement immediately. The captain was aghast to be told by Kilpatrick that his men were tired and needed rest, but that he should wait at headquarters for further orders and that reinforcements would be sent in the morning.

Sergeant Lyman Aylesworth of North Kingstown was captured at Middleburg (Varnum Memorial Armory Museum)

The Rhode Islanders were only five miles away and could easily have been reached. In effect, “Kilcavalry” had just sacrificed the First Rhode Island to its fate. In the general’s (partial) defense, his men had just fought a hard battle at Aldie a few hours earlier and had lost nearly 300 men.

Meanwhile, Stuart sent another brigade of Virginians under Colonel John R. Chambliss towards Middleburg. Darkness was beginning to settle in, and the Confederates did not know the strength of their enemy. The Rhode Islanders were outnumbered ten to one; events were about to go from bad to worse.[19]

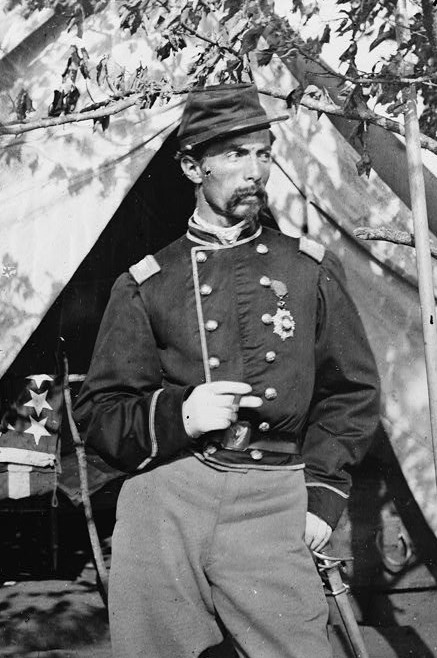

The initial Confederate assault began at 7:00 pm on the evening of June 17 after Robertson’s brigade of North Carolina cavalry moved into position. As the main body approached Middleburg, Duffie’s advanced pickets began exchanging carbine fire in a “lively skirmish” against troopers from the Fourth Virginia Cavalry. Henry Duxbury of Troop H was out on the skirmish line with ten other men under the command of Lieutenant Hebron Steere. The men took cover behind a small stone wall and then “gave them the carbines first, and then our revolvers, seventy-six shots in all.” After firing a few more carbine shots at the Rebels, Steere ordered his pickets to abandon their horses and run a mile through the woods back to Middleburg. The retreating men made it safely, quickly found other mounts in town, and rejoined the battle at the main barricade facing west. As the battle began Captain Bliss made a mental note that it was the anniversaries of the battles of Bunker Hill and Waterloo.

As the First Rhode Island was facing the North Carolina regiments, Colonel John Chambliss’s Virginia Brigade began closing off the roads around Middleburg, trying to seal the Rhode Islanders into their position. Major von Borcke and General Robertson ordered their men to draw sabers and charge on the thin skirmish line. The Prussian major recalled, “It lasted but a few seconds, for the enemy, unable to withstand the shock of our charge, broke and fled in utter confusion.” The Rhode Islanders mounted up or ran back down the road towards Middleburg to inform Duffie that the Confederates had returned in large numbers.[20]

Seeing an attack was about to be made on his flank by nearly 1,000 men of the Fourth and Fifth North Carolina, Duffie sent Major Preston Farrington and Troops F and G with orders to “fight as long as you think it any use.” The major took his men to a stone wall in a patch of woods; now they would outflank the flankers. The Rhode Islanders hid behind a stone wall and waited until the Confederates were only yards away. The Rebels rode right into the Rhode Island trap. The men fired their carbines and revolvers with deadly effect, with the Carolinians reeling from the shock. After shaking off the skirmish line of the First Rhode Island, Major Heros von Borcke led some of the party attempting to outflank the First Rhode Island. He remembered, “Bullets whizzed from either side- men and horses fell dead and wounded amidst the unavoidable confusion through the extreme darkness of the night, and for a time it seemed doubtful whether I should be able to hold my ground.” Because the Rhode Islanders were firing so rapidly von Borcke thought he was heavily outnumbered.

The Confederate officers yelled out, “Now boys form once more; we’ll give ‘em hell this time.” The mounted Carolinians charged for a third time before reeling back. The North Carolinians dismounted and loaded their Enfield rifle-muskets, and began to advance on foot into the woods, even as the Rhode Islanders continued to keep up a rapid fire from their concealed position. Lieutenant James M. Fales, in command of Troop F of the First Rhode recalled, “The slaughter was fearful; horses and men went down in wild confusion.”[21]

For two hours the Rhode Islanders held back Stuart’s cavalry, inflicting heavy casualties. Rebel Lieutenant Theodore Garnett recalled the actions of the First Rhode Island in the battle: “They behaved well, preventing us from pushing them by a strongly posted skirmish line, which owing to the coming darkness could not be dislodged from their position.”

The situation became critical as the ammunition began to run out. The First faced overwhelming odds as the Confederates closed in, their fire illuminating the night sky. Major Farrington sent Lieutenant Fales to tell Colonel Duffie that they were nearly surrounded. Duffie later wrote, “I could certainly have saved my regiment in the night, but my duty as a soldier and as a colonel obliged me to be faithful to my orders.” Even though he knew the situation was desperate, Duffie still attempted to hold Middleburg, rather than break out of it and save what men he could.

At nine p.m. a fresh force of Virginians entered the fray. The Confederates attacked in a “united front,” sweeping around the flanks of the First Rhode Island. Carbine ammunition was gone, and many men had already emptied their revolvers. All that remained were the horses and the cold steel of their cavalry sabers.

Duffie quickly contemplated the situation. Miraculously, not one man in the First Rhode Island had yet to be wounded. With no chance of reinforcement, Duffie finally realized that he had to disobey orders and abandon Middleburg, or his men would be slaughtered. He ordered the regiment to mount up and retreat.

Henry Brainerd McClellan, a member of Stuart’s staff, wrote the First Rhode Island “fought bravely and repelled more than one charge.” As Major von Borcke led reinforcements in the final attack against the fortified barricade, he noted, “The effect of which was to force our antagonists into a rapid retreat.”

Major Farrington and the Second Battalion were still concealed behind the wall. Duffie failed to notify the major that he was pulling out. Farrington took stock of the situation and led twenty-five men into a woodlot where they waited for a day, surrounded by the enemy but unseen, before galloping away.

Some 200 Rhode Island and New Hampshiremen had escaped. The rest helped cover the rear, or skedaddled, rejoining the regiment later. Some men, unable to mount up, were captured in the streets of Middleburg. For the main column under Colonel Duffie, the Battle of Middleburg had just begun.[22]

After riding a half mile out of Middleburg down the Hopewell Road, Duffie ordered the regiment to stop for the night and rest the horses in a small patch of trees. The enlisted men knew that the situation was critical. The regiment was still cut off and surrounded by enemy forces on all sides. Doctor Mann and Lieutenant Colonel Thompson pleaded with Duffie to order the regiment to mount up and retreat—they hoped to still make it back to Aldie and safety. There was still a chance that a large portion of the command could make it out. Duffie refused saying that he needed to rest the men and horses. Doctor Mann and some of the officers went to the extreme measure of telling Duffie that he should surrender the command if he would not fight or flee. Captain Bliss recalled, “By this time there was no soldier so dull as not to understand the desperate situation of the regiment.” Unknown to Bliss and the other Rhode Islanders, the Ninth Virginia Cavalry also camped for the night, only a hundred yards away.[23

At daybreak on June 18, Colonel Duffie sent Captain Bliss to reconnoiter. The captain was fired on instantly by members of the Ninth Virginia Cavalry. Colonel Richard Beale of the Ninth saw Duffie’s exhausted small force in the woods and ordered an attack, even as the Ninth “moved forward at a gallop.” Bliss reported to Duffie that they were surrounded. The buglers instantly sounded “”Boots and Saddles,” as Colonel Duffie jumped into the saddle shouting, “Let us go.” The Rhode Islanders joined the colonel and rode hard to the north with the Virginians in hot pursuit.[24]

Crossing a wheat field, Duffie saw more enemy cavalry to his right. He ordered the regiment to wheel into line to face the threat. The colonel knew there was no hope of his 200 men succeeding, but he ordered a charge. Captain Bliss in command of the head of the column ordered his men to draw sabers and in went the Rhode Islanders. The First Rhode Island charged headlong into the Ninth Virginia Calvary. The Virginians did not flinch and fought back with sabers and pistols The two sides bashed and slashed at each other. Second Lieutenant Joseph A. Chedell, a young pharmacist from Providence, was the first to die. As one Rhode Islander rode by the stricken officer’s body, he saw a Confederate trooper dismount and strip off Chedell’s boots. Four men in Troop M were killed in quick succession. Captain Bliss received a pistol shot to the arm. A Confederate closed in on Private Lawrence Cronan, who was carrying the guidon of Troop C. After being shot, Cronan passed the small pennant to a company sergeant as he fell from his horse and was later captured. The Virginian who took Cronan asked him why he did not surrender the guidon, to which he replied “It was not given to me for that purpose.”

Eventually, Duffie sounded the recall. He ordered his men to disperse and make their way as best as they could back to Centreville. The casualties had been heavy for the First Rhode Island: six killed and twenty wounded. Worse was to come, however, as the Federals began a gallop for freedom, with the Virginians within pistol shot range in pursuit.[25]

Lieutenant Colonel Thompson and Captain Bliss rallied six men from different troops. They pulled out their revolvers and charged again, scattering a smaller Confederate force. The survivors of the charge continued to ride as the Ninth Virginia pursued them on fresh horses. One Rhode Islander took four separate sabre blows to the head, yet somehow maintained consciousness and managed to escape.

The guidon bearer of Troop L lost his banner as it fell from his grip as the regiment galloped away. The flag was picked up by a member of Robertson’s brigade and became the only Rhode Island flag to fall to the enemy during the war.

Lieutenant Fales’s saddle came off his horse, pitching him to the ground. The bewildered Rhode Islander was captured by a red-headed South Carolinian. The Federal horses began to give out, as the Virginians yelled out, “Surrender, it’s no use, you can’t get away.” Private Everett C. Stevens’s horse collapsed and died. Colonel Duffie rode by him saying, “Poor Fellow.” One by one, the officers and men of the First Rhode Island began to give up. With their horses dying and with no ammunition, they found it impossible to carry on the struggle.[26]

Henry Duxbury, who had been posted on the skirmish line the night before, with several others galloped for their lives out of Middleburg. With his ammunition gone, all the young soldier could do was try to ride as fast as possible. He remembered as the Confederates pursued him:

I saw them a few hundred yards behind, yelling, firing, and ordering us to halt. Here was a scene I cannot describe; some were killed and some were thrown from their horses, and the horses without any riders kept right on with us; the road was narrow in places, and the riderless horses jumped here and there. I would sometime look behind and they would be close by me, and they were shooting all the time. One man was killed by my side. Sometimes they would be close on me, and then I would gain some on them; after a time we were pretty well strung out.

Duxbury continued to gallop and thought he had reached safety when his horse suddenly stopped in the middle of the road. Despite trying to spur and whip the beast, the horse would not budge. The Confederates soon captured the young Rhode Islander and took his prized carbine, but did not notice the Colt .44 revolver on his belt, which Duxbury promptly threw into the woods so the enemy would not obtain it.[27]

As he was being pursued, Captain Joshua Vose, the commander of Troop A, recalled, “I plunged my spurs in my horse and was on the side of the mountain while a perfect shower of lead fanned my face.” While Vose managed to escape, the majority of Troop A was not so fortunate.[28]

Captain Bliss’s horse had finally had enough—it threw the rider off even as the beast carried on. Bliss was fortunate to retain his pistol and saber. Finding five other men from the regiment, he ordered them to abandon their exhausted horses and continue on foot. That night a rain storm hit as the survivors crouched into several small shelter tents, eating a meal of cornmeal and milk purchased from a local Unionist. In the event that he was killed before he reached Centreville, Captain Bliss wrote a letter to a friend in Providence:

Our regiment has just been cleaned up. It is to bad to slaughter a regiment needlessly as we were. I may be egotistical, but I believe that if I had been in command I would have safely extricated the regiment from its perilous condition. I would have gone to a house, taken a man and told him to take me across Bull Run Mountain and if he brought me amongst the Rebs I would have blown his brains out. We were halted all night when we out [ought] to have been marching.

Captain Bliss and his five men eventually made it to Washington. He later mailed the letter to a friend in Providence, but asked that the contents not be published, due to its damning of Colonel Duffie.[29]

As the men fell out of column, they were quickly captured. The color bearer of the Rhode Island flag broke the flag from its staff and stuffed it into his jacket, thus avoiding the flag’s capture. Sergeant George A. Robbins broke free with the National colors; he was promoted to first lieutenant for saving the flag.

Some of the captured were not too concerned about their fates. Doctor Mann knew that surgeons were typically released after being captured; he set about to treating the wounded on both sides. A Confederate told Mann that he would be shot, but the physician knew the threat was an idle one.

Lieutenant George Beale of the Ninth Virginia reported that his command captured nearly 160 of the Rhode Islanders. He recalled, “It fell to my lot to assist in paroling, and I had occasion in the performance of this duty to observe the fine demeanor of brave men in the hour of deep mortification and calamity.” Although they had been defeated, the enemy respected the gallant, albeit futile effort made by the First Rhode Island Cavalry.[30]

By 10:00 a.m. of the eighteenth it was over: nearly the entire First Rhode Island Cavalry had been captured. Lieutenant Garnett recalled the appearance of the captured troopers: “The prisoners were brought in covered with dust and dirt to such a degree that Federal and Confederate could scarce be distinguished apart.”

That night the prisoners were gathered in a tight circle in Middleburg. Private Welcome A. Johnson saw the bodies of thirty dead Confederate cavalrymen on the porch of a local house, including a major. Lieutenant Fales thought the number was closer to forty. The young officer noted southern women placing “wreaths of flowers on their breasts.” The angry Virginians said that the Rhode Islanders were responsible for the deaths. On the nineteenth, the captured men began a one-hundred mile forced march to Belle Isle and Libby Prison.[31]

As the Rhode Islanders were being shot down and captured in the fields around Middleburg, Kilpatrick finally summoned reinforcements to head towards Middleburg and assist Duffie. At day break, the force set off to relieve the Rhode Islanders, but continually found themselves stopped by small parties of Confederates, as well as “fallen trees, burned bridges, and obstructions of all kinds.” Captain Allen and Private Charles Green rode at the head of the column, eager to return to their comrades. By the time they got to Middleburg, Private Green was sickened by the delay. “We at last arrived at Middleburg with the reinforcements, but it was too late to be of much use.” The First Rhode Island Cavalry had simply evaporated. Allen and his men were ordered to proceed to Washington with the information they had carried.[32]

After escaping Stuart’s men, Colonel Duffie found four officers and twenty-seven men and continued on his journey back to Federal lines. Stopping at Manassas Junction to rest, Sergeant Lyman Aylesworth found Colonel Duffie sitting on a fence weeping and continuously saying, “My poor boys, all are gone, all are gone.” Captain Francis A. Donaldson of the 118th Pennsylvania was one of many Union soldiers marching north in pursuit of Lee’s Army. Donaldson recalled seeing what was left of the First Rhode Island on the march, and plainly stated, “Col. Duffie’s command was destroyed.” Duffie finally arrived in Washington at 1:30 on the afternoon of June 21. Here he met Captain Allen and several members of the regiment who had made it to the city before him. Reporting to headquarters, Duffie said, “Here is all I have left of my fine regiment. I obeyed the order. We went. They cut me up. But my men did well; they fought hard. I saw General Hooker he sent me here to recruit and make a fine regiment once more.”[33]

The colonel established regimental headquarters on Arlington Heights and began the process of rebuilding the shattered regiment. In the next few days the remainder of the men made it into camp. Major Farrington brought back two officers and twenty-three men who had remained hidden in the woods while the rest of the regiment escaped with Duffie. Eventually thirty-six other men made it back to Washington on their own. Of the 280 men who charged into Middleburg, six were killed, twenty wounded (most of whom were also listed as captured), and 210 captured, of whom forty escaped from captivity. Thus, 170 men from the First Rhode Island Cavalry were sent to prison in Richmond. Many of the prisoners were held for about five weeks before being exchanged—one unlucky sergeant lost thirty-five pounds in the five week period. Others remained in captivity for years, with some ending up in 1864 at the horrible Andersonville prison, where many died.

The First Rhode Island Cavalry had been annihilated; the regiment sustained over eighty percent casualties at Middleburg. One member of the First Rhode Island recalled, “It is only marvelous that any of the command escaped death or capture. We were literally thrown into the jaws of war.”[34]

As the survivors of the First Rhode Island Cavalry regrouped and reequipped on Arlington Heights, Colonel Duffie received an unexpected reward. His nomination for promotion to brigadier general for his performance at Kelly’s Ford had been acted upon, and he was promoted, with the date of rank from June 17, 1863. A shocked Duffie wrote, “My goodness, when I do well, they take no notice of me. When I go make one bad business, make a fool of myself, they promote me, make me general.”

For the rest of their lives, the men who were both captured at and near Middleburg, and survived the war tried to make sense of what happened to them, and why the First Rhode Island Cavalry had been needlessly sacrificed. Lieutenant Colonel Thompson blamed Colonel Duffie’s ambition, saying “He could not bear to retreat.”[35]

All in the regiment blamed the colonel for the high losses. Captain Bliss claimed it was his French training that hindered him. Any American officer would have seen the threat and retreated, even though he might be court martialed for disobeying orders. Colonel John S. Mosby, later the famed guerilla chieftain, wrote of First Rhode Island Cavalry at Middleburg, “Duffie’s folly is an illustration of the truth of what I have often said—that no man is fit to be an officer who has not the sense and courage to know when to disobey an order.” Duffie was trained in the old European ways and followed the orders to the letter—thus, he remained in position.

Many of the enlisted men believed that the one fatal mistake Duffie made was ordering the men to rest after being driven out of Middleburg. If they had ridden through the night, they could have been saved.[36]

Captain Bliss believed that although the men of his regiment were overwhelmed, they indirectly contributed to the victory at Gettysburg. By surprising and scattering Stuart and his staff at Middleburg, the First Rhode Island had drawn the Confederates away from Aldie, which led to the fights west of Middleburg on June 19 and at Upperville on June 21, enabling Pleasonton’s horse soldiers to fight their way across the Loudoun Valley. Stuart wanted revenge for being caught off guard by the Rhode Islanders on the seventeenth. This led him on the raid into Pennsylvania, which deprived Lee of his “eyes and ears” as the Confederate infantry marched towards Gettysburg in late June 1863.[37]

Although the recovery of the First Rhode Island Calvary precluded its participation on the field at Gettysburg, several members of the regiment were there as orderlies at Third Corps Headquarters. Corporal Edward F. Moore and Private Charles H. Clement of New Hampshire Troop L were killed on the second day by shell fire. Other members of the regiment were lucky to avoid Middleburg altogether. On February 24, 1863, Corporal William E. Walsh and his vidette post were captured along the Rappahannock River. Taken to Libby Prison, Walsh was released in June and sent to Baltimore. Walsh remained there during the Gettysburg Campaign, helping to defend the city. Afterwards he returned to Washington and returned to Troop A of the First as the regiment rebuilt its ranks. By August 1863, a sufficient number of men were back on duty to perform picket duty and reinforcement to Union parties searching for guerillas in northern Virginia. The men complained that instead of trying to rebuild the regiment as a cohesive force, they continued to be sent out in small groups on scouts and guerilla missions as being “so scattered as to nearly block out our existence.”[38]

Following the Battle of Middleburg, the First Rhode Island Cavalry was a marked regiment. It never again was allowed to serve in the Army of the Potomac. The New Hampshire Battalion was detached in early 1864 and returned back to the Granite State to form the nucleus of the First New Hampshire Cavalry. Although called Rhode Islanders during their service, the New Hampshire troopers had been an integral and well-regarded part of the regiment. Governor James Y. Smith tried to order the First Rhode Island home to recuperate and recruit, but instead the remains of the regiment remained in Washington, receiving nearly “worthless” bounty men for recruits.[39]

The First Rhode Island Cavalry was never the same after Middleburg. It was filled up with bounty jumpers and raw recruits after the engagement, many of whom promptly deserted. Many of the original members who returned to the regiment were captured again in the 1864 campaigns and died at Andersonville.

In 1864, the First Rhode Island Cavalry was ordered into the Shenandoah Valley and played a leading role at Waynesboro and Mount Jackson. The First Rhode Island became one of the few regiments to serve in the Reserve Cavalry Brigade, which was composed of United States Regulars. In April 1865, as the defeat of Lee’s army loomed, the First Rhode Island was among the first to close in on Appomattox. By war’s end, only 125 men were left, while their guidons recorded fifty-six battles and skirmishes.[40]

Captain Bliss was awarded the Medal of Honor for heroism at Waynesboro in 1864. He was wounded two more times during the war, and spent five months in prison. He returned home, resumed his law practice and became a state representative, as well as a judge. He also served as Grand Master of the Rhode Island Masons. Bliss was highly active in regimental affairs, and frequently wrote about his wartime experiences; he lived until 1928 when he died at the age of ninety-one.

Dr. Augustine Mann survived the war and practiced medicine for over sixty years in northern Rhode Island. He was active in the Grand Army of the Potomac.

Major Preston M. Farrington survived the war, and lived to be ninety-nine years old, the last surviving field officer from a Rhode Island regiment. The majority of the surviving troopers returned to Rhode Island and New Hampshire, decorating their homes with war relics and remembering that terrible day in June 1863.[41]

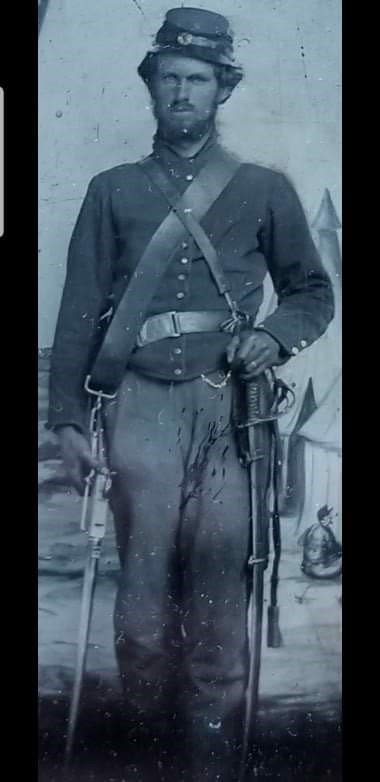

Captain Joshua Vose of Westerly served as the commander of Troop A, First Rhode Island Cavalry. He had a very narrow escape at Middleburg on June 18, 1863, nearly being captured with his entire company. He survived the war unscathed and mustered out in the fall of 1864. Captain Vose moved to Providence after the war and ran a fruit store (Robert Grandchamp Collection)

General Duffie became a marked man. Transferred to the Army of West Virginia, he served credibly as a division commander in the 1864 Valley Campaign. He led a cavalry charge that contributed greatly to the Union victory at Cedar Creek. Sent to find John Mosby and his guerilla band, Duffie stated he would capture the “Gray Ghost.” It was, however, Mosby who captured Duffie two weeks after Cedar Creek. The Frenchman was imprisoned for the rest of the war. Mustering out of the service, Duffie entered the diplomatic corps and became a naturalized American citizen in 1867. Assigned as a United States consul to Spain, he spent the remainder of his life in the service of his adopted country, while continuing to perfect his English skills.

Duffie attended only one reunion of the First Rhode Island Cavalry after the war. He continued to suffer from asthma and searched in vain for a miracle cure. He died of tuberculosis in 1880 and was buried on Staten Island. In 1889, the survivors of the First Rhode Island Cavalry erected a monument to his memory in Providence.[42]

June 18, 1863 was the most important day in the history of the First Rhode Island Cavalry, and in future years June 18 was frequently the day of regimental reunions. Even years after the battle, the memory of Middleburg continued to haunt the veterans of the regiment. Writing to a comrade from Maine in 1894, one First Rhode Island veteran stated:

An hour and a half march would have put Union troops against Stuart’s forces near Middleburg and saved many brave Rhode Island troopers from starving to death at Andersonville. Somebody blundered. The Generals are dead now and we shall never know why the First Rhode Island was left to its fate without the help from brave comrades who if they could have known the full situation would have begged for the order to advance.

Indeed, somebody had blundered. The main culprits were Colonel Duffie for following his orders with no interpretation for the actual situation he encountered and General Kilpatrick for ordering the regiment to advance alone behind enemy lines. They are equally to blame for the events of June 17-18, 1863 near Middleburg, Virginia. The end result of these decisions was the near annihilation of the First Rhode Island Cavalry.[43]

NOTES

[1] Frederic Denison, Sabres and Spurs: The First Rhode Island Cavalry in the Civil War (Central Falls: The Association, 1876), 29-44; First Rhode Island Cavalry, Regimental Books and Papers, Rhode Island State Archives (RISA), Providence, RI. William Sprague Letter Books, RISA. [2] George N. Bliss, How I Lost My Saber in War and Found it in Peace (Providence: Snow and Farnum, 1903), 43-44; Denison, Sabres and Spurs, 29-44; Manufacturers’ and Farmers’ Journal, December 16, 1869; Ordnance and Quartermaster Returns, First Rhode Island Cavalry, RISA. [3] George N. Bliss, Reminiscences of Service in the First Rhode Island Cavalry (Providence: Snow and Farnum, 1878), 15; Dennison, Sabres and Spurs, 54-98. [4] John Russell Bartlett, Memoirs of Rhode Island Officers: Who Were Engaged in the Service of their Country during the Great Rebellion with the South (Providence: Sydney S. Ryder & Brothers Press), 209-212. [5] Eric Wittenberg, “Brig. Gen. Alfred N. Duffie,” June 18, 2015. Accessed June 16, 2016. At http://civilwarcavalry.com/?p=4221. [6] Bartlett, Memoirs of Rhode Island Officers, 209-212; Bliss, Reminiscences of Service, 63-66; Denison, Sabres and Spurs, 103-107; Alfred N. Duffie to William Sprague, July 27, 1862, copy in author’s collection. [7] Bliss, How I Lost My Sabre, 5-7; Dennison, Sabres and Spurs, 55-98; Elisha Dyer, Annual Report of the Adjutant General of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, for the year 1865, Cor., rev., and republished, Volume II (Providence: E.L. Freeman & Sons, 1893), 12-158; John J. Spencer, Service File, National Archives, Washington, D.C.; Lillie B. C. Wyman, A Grand Army Man of Rhode Island (Newport: Graphic Press, 1925), 15-16. [8] Manufacturers’ and Farmers’ Journal, December 16, 1869; Denison, Sabres and Spurs, 134-194. Denison served as chaplain of the regiment from 1861-1863. His papers are housed at the Westerly Public Library, Westerly, Rhode Island. [9] Jacob B. Cooke, The Battle of Kelly’s Ford (Providence: Snow and Farnum, 1887), 1-29; Bartlett, Memoirs of Rhode Island Officers, 211-212; Providence Evening Press, March 25, 1863. [10] George N. Bliss, The First Rhode Island Cavalry at the Battle of Middleburg, Va. (Providence: Snow and Farnum, 1889), 1-5; Providence Evening Press, June 14, 1863. Captain Bliss’s personal papers are housed at the Rhode Island Historical Society. Although many of the publications cited in this article were written after the war, a comparison of them to Bliss’s letters clearly indicates he copied the majority of his wartime letters into his postwar remembrances. His work on the Battle of Middleburg consists of two sections, the first is Bliss’s memoirs of the battles, while the second or appendix contains letters written to Bliss by Union and Confederate participants in the battle and pursuit. [11] United States War Department, War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 70 vols. in 128 parts (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), series 1, vol. 27, 962-963. (Hereinafter referred to as O.R. All subsequent references are to series 1.) [12] Bliss, First Rhode Island at Middleburg, 45-51. [13] Preston M. Farrington, “Recollections of the Battle of Middleburg,” n.d., Rhode Island Historical Society (RIHS), Providence; Charles O. Green, An Incident in the Battle of Middleburg, VA. June 17, 1863 (Providence: The Society, 1911), 1-2; Henry Brainerd McClellan, The Life and Campaigns of Major-General J.E.B Stuart: Commander of the Cavalry of the Army of Northern Virginia (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1885), 303-304. [14] Bliss, First Rhode Island at Middleburg, 6-7, 45-51. O.R. 27, 962-963; George William Beale, A Lieutenant of Cavalry in Lee’s Army (Boston: Gorham Press, 1918), 100-101. [15] Heros von Borcke, Memoirs of the Confederate War for Independence (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1867), 232: 414-416; McClellan, Life and Campaigns of Stuart, 303-304. [16] Theodore Garnett, “Theodore Garnett Recalls Cavalry Service with General Stuart, June 16-28, 1863,” James R. Jewell, ed., The Gettysburg Magazine, no. 20 (January 1999), 45. Theodore Garnett, “Theodore Garnett Recalls Cavalry Service with General Stuart, June 16-28, 1863,” James R. Jewell, ed., The Gettysburg Magazine, no. 20 (January 1999), 45. [17] Garnett, “Cavalry Service,” 45. [18] Denison, Sabres and Spurs, 233-235; Farrington, “Recollections of Middleburg;” Garnett, “Cavalry Service,” 46; von Borcke, Memoirs of the Confederate War, 415. [19] Denison, Sabres and Spurs, 233-235; O.R. 27, 963: 965; Green, An Incident, 1-19. For one of the best accounts of the fighting at Aldie, refer to Edward P. Tobie, History of the First Maine Cavalry, 1861-1865 (Boston: Press of Emery & Hughes, 1887) 159-168. [20] Bliss, First Rhode Island at Middleburg, 12-13: 40-43; von Borcke, Memoirs of the Confederate War, 415. [21] Von Borcke, Memoirs of the Confederate War, 415-416; James M. Fales, Prison Life of James M. Fales (Providence: N. Bang Williams, 1882), 5-6; Farrington, “Recollections of Middleburg;” Garnett, “Cavalry Service,” 46. [22] George N. Bliss, Duffie and the Monument to His Memory (Providence: Snow and Farnum, 1890), 22-24; Bliss, First Rhode Island at Middleburg, 12-13; Farrington, “Recollections of Middleburg;” Garnett, “Cavalry Service,” 46; McClellan, Life and Campaigns of Stuart, 303-304; von Borcke, Memoirs of the Confederate War, 415-416; Beale, Lieutenant of Cavalry, 100-101. [23] Fales, Prison Life, 7-8; Wyman, Grand Army Man, 16-20; George N. Bliss letters, RIHS; Beale, Lieutenant of Cavalry, 100-101. [24] Bliss, First Rhode Island at Middleburg, 18-20; Denison, Sabres and Spurs, 252-253; Beale, Lieutenant of Cavalry, 100-101; Wyman, Grand Army Man, 16-20. [25] Bliss, Reminisces of Service, 20-21: 47; Denison, Sabres and Spurs, 236-239; Beale, Lieutenant of Cavalry, 100-101; Fales, Prison Life, 8-9; Bartlett, Memoirs of Rhode Island Officers, 440-441; O.R. 27 963-964. [26] In 2008, the North Carolina National Guard returned the guidon to Rhode Island, and it is now in the custody of the Rhode Island National Guard. Denison, Sabres and Spurs, 254-256: 259; Fales, Prison Life, 8-9; Everett C. Stevens, A Forlorn Hope (Providence: Snow and Farnum, 1903), 1-2; Francis A. Donaldson, Inside the Army of the Potomac: The Civil War Experiences of Captain Francis Adams Donaldson, edited by J. Gregory Acken (Stackpole Books: Mechanicsburg, PA, 1998), 284. [27] Bliss, First Rhode Island at Middleburg, 40-43. [28] Joshua Vose letter, nd, in Robert D. Maddison, “Introduction,” in the 1994 reprint of Sabres and Spurs (Baltimore: Butternut & Blue, 1994). [29] George N. Bliss to David V. Gerald, June 18, 1863, RIHS. [30] Bliss, First Rhode Island at Middleburg, 24-26; Wyman, Grand Army Man, 20-21; Beale, Lieutenant of Cavalry, 100-101. [31] Denison, Sabres and Spurs, 254-256; Fales, Prison Life, 9-10; Garnett, “Cavalry Service,” 46. [32] Green, An Incident, 19-20; Donaldson, Inside the Army of the Potomac, 284. [33] Denison, Sabres and Spurs, 254-256:259. [34] Bliss, First Rhode Island at Middleburg, 28: 43; Denison, Sabres and Spurs, 237-239; Farrington, “Recollections of Middleburg;” Dyer, Annual Report, 12-158; Stevens, A Forlorn Hope, 8-9. Although the casualties were high, the overwhelming majority were prisoners who were quickly released and returned to the regiment. Despite this, the First Rhode Island Cavalry was rendered hors de combat until 1864. [35] Bliss, First Rhode Island at Middleburg, 47-50; Bartlett, Memoirs of Rhode Island Officers, 209-211. [36] Denison, Sabres and Spurs, 258-261; John S. Mosby, Stuart’s Cavalry in the Gettysburg Campaign (New York: Moffat, Yard & Company, 1908), 70-71. [37] Bliss, First Rhode Island at Middleburg, 30. [38] John W. Busey, These Honored Dead: The Union Casualties at Gettysburg (Hightstown, NJ: Longstreet House, 1996), 307; Denison, Sabres and Spurs, 271-307; William E. Walsh, “Narrative of Service in the First Rhode Island Cavalry,” Special Collections, Phillips Library, Providence College, Providence, RI; Providence Press, August 5, 1863. [39] Denison, Sabres and Spurs, 330-341; First New Hampshire Cavalry Veterans Association, Papers, New Hampshire Veterans Association, Weirs Beach, NH; Providence Press, June 26, 1863. [40] Denison, Sabres and Spurs, 342-458; Casualty Returns and Regimental Books, First Rhode Island Cavalry, RISA. [41] Bliss, How I Lost My Saber, 7-15: 40; Wyman, Grand Army Man, 31-34; Denison, Sabres and Spurs, 598-600. [42] Bliss, Duffie Monument, 25-36; Bartlett, Memoirs of Rhode Island Officers, 215-219. [43] First Rhode Island Cavalry Veterans Association, Reunion Ribbons, author’s collection; George N. Bliss, “A Review of Aldie,” The Maine Bugle, Campaign I, Call II (April 1894), 124-125.