The Great Swamp Fight on December 19, 1675, in King Philip’s War, forever destroyed the power of the Narragansett tribe. What is less well known are earlier destructive raids, including on December 14 by Massachusetts, Plymouth and Connecticut colonists based at Richard Smith’s trading post (now Cocumcussoc) north of present-day Wickford against a Narragansett town ruled by Queen Quaiapen (sometimes called Queen Magnus, Maquus, Matantuck, or the Old Queen, as well as other names). One colonist raider, writing from “Mr. Smith’s” on December 15, reported that “We have burned two of their towns,” including “the old Queen’s quarters consisting of about 150 . . . large wigwams and seized and slain 50 persons” and took about 40 prisoners.[1] Where this town was located is not known, but it was within striking distance from Smith’s trading post.

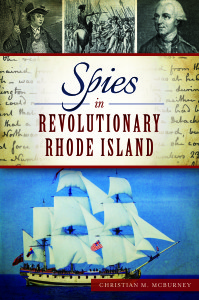

Plan of Queens Fort sketched by Henry B. Hammond, November 1865. The outline of the walls are very noticeable and mostly unbroken (Rhode Island Historical Society Collections, Oct. 1923)

Quaiapen, with perhaps 200 warrior, women and children survivors, reportedly took refuge in a stone fort deep in the forests of what is now Exeter, some nine miles northeast of the site of the Great Swamp Fight. The fort was constructed by Stonewall John (his Indian name has been lost). There, the queen and her people would be safe.

Several months later, as King Philip’s War waned, it was hoped the war would end soon, especially now that King Philip (also called Metacomet) of the Wampanoags had fled his base at Bristol Neck and southern New England and was supposed to be somewhere north of Albany. The elderly Queen Quaiapen, sister to the chief sachem of the Niantics, Ninigret, and the wife of the eldest son of the great Narragansett sachem Canonicus, agreed, but it was not quite so simple. Raids by parties of white soldiers from the Massachusetts, Plymouth and Connecticut colonies into the Narragansett country searching for Indians continued. The fortification in Exeter was just three-and-one-half miles from Richard Smith’s trading post, which colonial soldiers continued to use as a base for staging raids.

With warm weather, pressure on Queen Quaiapen to quit the fort and avoid being confined to a single location was great and finally persuasive. Reportedly against Stonewall John’s advice and that of her chief counselor, Potuck, she led her people north in June 1676. On July 2, 1676, in a swamp in North Smithfield, her band was attacked by a troop of roving Connecticut horsemen led by Major John Talcott. A total of 171 of her people were killed or captured. The next day Talcott’s soldiers attacked Potuck’s smaller band at Warwick Neck. The queen, Stonewall John, and Potuck were among the killed.[2] Most of the prisoners were likely sold as slaves in the Caribbean.

The abandoned Queen’s Fort, as it would become known, was not discovered by the English until months after the war ended.

There is debate about the background of Stonewall John. The early chroniclers say he was an Indian versed in masonry which he had learned from the English. Legend in Rhode Island says he was a renegade English engineer who had constructed forts in England. More likely, this last legend grew because white storytellers could not believe that an Indian could construct the strong fortress. This legend seems counter to the well-established reputation of Narragansett Indians that continues to this day for their expertise as stone masons.

Contemporary references to Stonewall John exist. One history of King Philip’s War by an anonymous author, published in 1676, and probably authored by a Massachusetts colonist, wrote of “An arch villain of their party . . . famously known by the name of Stone-Wall or Stone-Layer John . . . .” The author added that Stonewall John, “being an active and ingenious fellow . . . had learnt the mason’s trade, and was of great use to the Indians in building their forts, etc….” Another Massachusetts historian, in a book published in 1677, wrote that on December 15, the day after the raid on Quaiapen’s village, “an Indian called Stonewall John” came to Richard Smith’s trading post and put out peace feelers on behalf of Narragansett sachems. A colonial officer wrote in a January 1676 letter from Smith’s, “Dec. 15, came in John, a rouge, with pretense of peace.”[3]

Stonewall John did construct Queen’s Fort with a sophistication unknown to any other Indian of the times. All other known forts of the Indian tribes in southern New England were large enclosed stockades, made of logs or wooden poles set into the ground and stone-filled ditches. Typically, but not always, they were built in swamps. Queen’s Fort was built of stone and on a hill.[4]

Queen’s Fort was unique. Not only did it stand atop a fairly steep hill, it was built in an area where boulders were naturally deposited by glaciers. It is located just off Stony Road on the Exeter-North Kingstown line, about one-quarter of a mile west of Route 2.

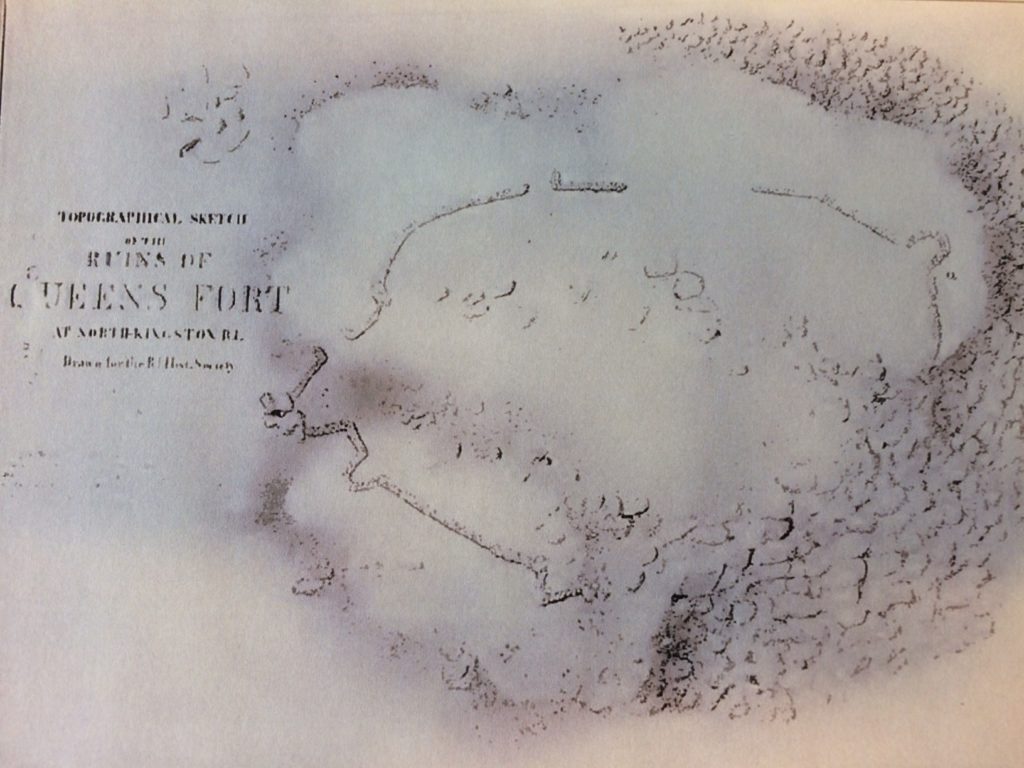

Map of Queen’s Fort drawn by Sidney Rider drawn about 1900; the measurements in feet are indicated (Rider, Lands of Rhode Island: As They Were Known to Caunounicus and Miantunnomu, 1904)

Had it been attacked by New England colonists in King Philip’s War, it would have been difficult to seize. The single path to the summit winds among boulders. On the southeast side a fall of great boulders, down the cliff side, made a wall at the top unnecessary. From the battlements, a brisk fire from muskets—and the Indians possessed firearms equal to those of their enemy—would have made an assault doubtful of success absent overwhelming manpower or firepower on the side of the white soldiers.

Recently, some current Narragansetts argue that the site, because it was on a hilltop, was not a fort but instead was a sacred place.[5] An archeologist study disagreed, stating, “seventeenth-century Native forts in southern New England are located on hilltops as well as swamps. A stone fort on a boulder-covered summit may have provided a well-camouflaged hiding place” and could be well-defended.[6] The argument that the site was not a fort is a weak one, given the description of the stonewalls and their locations and military design at Queen’s Fort over the years and the maps done of the site in the late 1800s and early 1900s, all as set forth in this article. Moreover, there is a reference in the historical record to a second stone fort on the Exeter-North Kingstown border, within about six miles of Queen’s Fort, called Stony Fort, that also existed in the seventeenth century and was likely made by Narragansetts (though its location is not now exactly known).[7] In addition, the archeologist Patrick Malone, an expert on military technology in seventeenth century New England, wrote that the fort’s sophisticated design points to Stonewall John as the architect, who may have become familiar with defensive structures Europeans built to enclose their settlements.[8]

While Queen’s Fort would have presented a strong defensive fortification, it is doubtful that Quaiapen’s followers would have lived within the confines of the fort. More likely, they kept a village nearby, and were ready to retreat to the fort if necessary.

Today, Queen’s Fort is still recognizable, but time has taken its toll. One of the few indigenous stone architectural treasures of New England, it was forgotten, neglected, and much of it has disappeared. Frost, the wild growth of chestnut and oak trees whose trunks and roots have pushed aside even large boulders, and years of vandalism have displaced the stone walls.[9] It has been a spot known by teen-age drinkers over the years, as well as pagan spiritualists, who may have moved stones around.

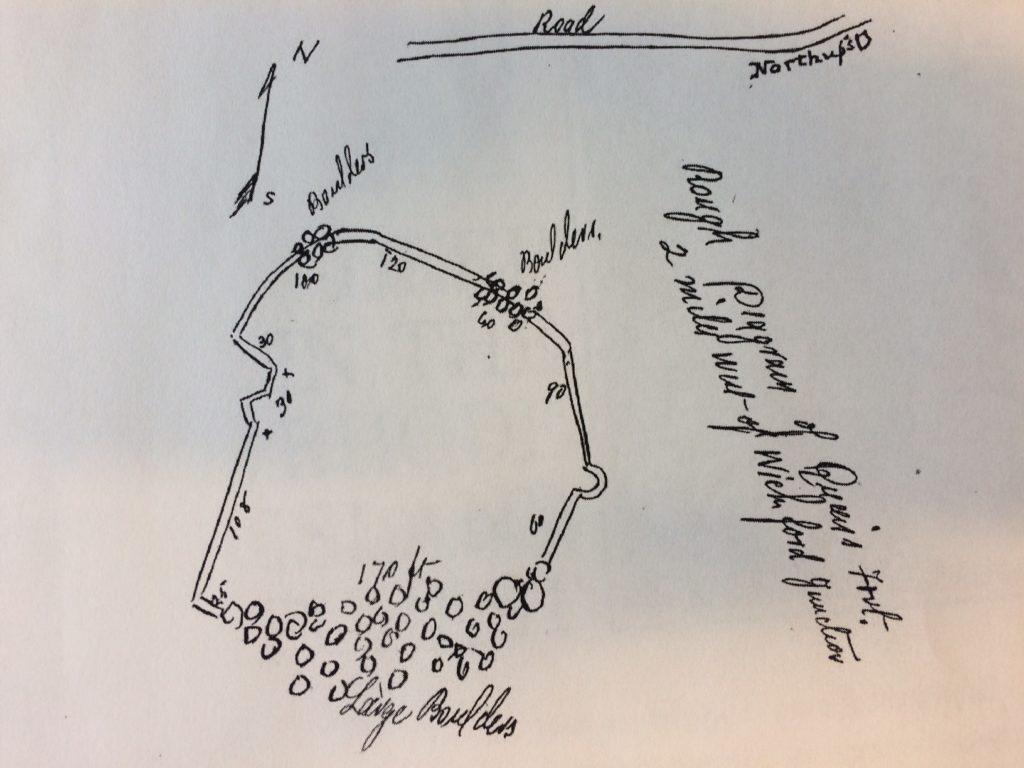

Photograph taken around 1980 shows stonewalls in better shape than they are today (National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form, for Queen’s Fort, 1980)

Today, at a quick glance, the site may appear to be merely a geologic wonder of boulders strewn on hilltops and on hillsides. But upon closer inspection, lines of tumbled-down stonewalls and curved stone projections at the corners (bastions) still exist. The fort’s outlines indicates that it was roughly square in outline with stone walls approximately 200 feet long on each of three sides, with the fourth side being an impenetrable mass of boulders.

Historical records—including recollections and maps– indicate that Queen’s Fort once was a well-defined fortification.

The first reference to Queen’s Fort I found in Rhode Island records is in the colony’s official records for 1724, only 48 years after Quaiapen led her people to the north. In dividing North Kingstown into three districts for purposes of forming three companies of militia, one of the boundaries was referred to as “Queen’s Fort, so called.”[10] No historian has previously mentioned this reference.

Beginning in the nineteenth century, historians began to note the existence of the fort, and focus on a nearby a natural underground cavern that was called the Queen’s Chamber. Elisha R. Potter, Jr. of Kingston, the earliest historian of the Narragansetts, in 1835 recorded:

“There are the remains of an Indian Fort still known by the name of Queen’s Fort, near the line between North Kingstown and Exeter. It is on the summit of a high hill completely covered with rocks, and the fort appears to have been surrounded with a strong stone wall. There is a hollow in the rock known as the Queen’s bedroom and a large room, the entrance of which is nearly concealed, which is supposed by tradition to have been a hiding place for the Indians, in which arrow heads etc. have been often found.”[11]

In 1889 J. R. Cole, in his history of Washington and Kent Counties, wrote of Queen’s Fort:

“The sides of this hill on the east, southeast and south are covered with a mass of stones more or less irregular in shape, and so thrown together as to form natural caverns and retreats. The hill is covered with a thrifty growth of chestnut trees. On the top of the hill is a stone wall fortifying its approach. The wall runs east and west, and at either corner were once stone huts, probably the residence of some Indian chief. From both of these points the wall runs south, but only for a short distance, the south side being naturally fortified. . . In a small valley just west of the wall is a unique collection of stones forming a natural cavern, in which is it said Maquus, the squaw sachem [other names for Quaiapen], once resided . . . .”[12]

James Arnold, a South County historian, in a letter published by the Rhode Island Historical Society, wrote in 1898 about the Queen’s Chamber:

“Starting from the west side you crossed some rocks and there came a break and then the great cluster. The chamber is well towards the west part of this last clump of stones. There is a large flat stone that covers the entire chamber and it’s very close except on the south side which gives an opening of about two feet in height and the width of the chamber in length. The chamber itself is about 10 feet square and about six feet in the clear. I could reach the ceiling with my hands when I was in it. The room is very square and well proportioned. I am really sorry you did not find it but if one is not very careful he is apt to go by it.”[13]

In the same year of 1898, Rhode Island historian Sidney S. Rider wrote of the Queen’s Chamber, in a letter also published by the Rhode Island Historical Society, “The Queen’s Bed Chamber is somewhat difficult of access. Some agility is required both to get in and get out again. It is about 7 feet in height and will hold about 20 men.”[14] In his Lands of Rhode Island, published in 1904, Rider wrote about the Queen’s Chamber, which must have been remarkable to behold:

“Many boulders lie within the walls of this fort; beneath some of them are excavations sufficient to give shelter to one or two persons, but these are nothing taken in comparison with the Queen’s Chamber. This extraordinary chamber is not within the fort, but outside, west, and distant about 100 feet. It consists of an open space beneath an immense mass of boulder rocks; the tallest man may stand within it; the floor is of white sand; the entrance is so hidden that six feet away it would never be suspected; the boulders piled above it represent a thickness of fifty or sixty feet.”[15]

The Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration produced a historical and geographical guide to Rhode Island in 1937. The guide describes Queen’s Fort, located off Stony Lane, as follows:

“The fort is a low wall of rocks rudely piled together on a hilltop straddling the North Kingstown-Exeter boundary line. Surrounded by timber and huge rocks, it is unapproachable from the south owing to the many immense boulders with the hill is strewn; access to the other approaches is difficult owing to the steepness of the hillside. Many boulders lie within the fort, and beneath some are excavations large enough to shelter several people. The Queen’s Chamber, a little outside the fort to the west, is a large opening beneath a huge pile of rocks. The floor is covered with fine white sand and the entrance is so hidden as to be unnoticed a few feet away.”[16]

Stuart J. Goulding wrote an article about Queen’s Fort in 1969 for Yankee Magazine. Based on his recollections, Queen’s Fort began to break down after 1937. He recalled, “As a boy [around 1949], I and others spent days searching for the Queen’s Chamber, certain that it contained skeletons and treasures; we never found it, nor do I believe it has been found since.” Goulding noticed the rapid deterioration of the fort from the time he visited it in 1949 to the time he wrote about it in 1969. He wrote, “Twenty years ago [1949] when I had last visited the fort, the walls were nearly intact and almost waist high. Today [1969] they are nearly all tumbled down and it is difficult to trace the battlements and to distinguish their boulders from other boulders strewn over the large site.”[17]

Still, as late as 1969, Gouldring could make out the outlines of the stonewalls of the fort:

“The wall itself runs 25 feet west from the great boulders to make a right angle north. One hundred and eight feet north there is a V-angle bastion 30 feet at its widest. The wall continues a few feet west from this and then 180 feet to a large pile of natural boulders. From this point, the wall makes a wide curve along the northern contour of the hill for 120 feet more where it meets still another group of boulders 40 feet wide at the ground level. From these boulders the turn is southeast for 90 feet to a half-moon-shaped bastion. From there it is 60 feet to the great boulder fall.”[18]

Carl Pallister stands in the remains of a former bastion at Queen’s Fort, November 25, 2018 (Christian McBurney)

Gouldring continued, “What lends credence to the legend that Stonewall John was a European or Englishman are the bastions and the right angles. They are found in no other fort the eastern Indians constructed nor, indeed, are there any known that were built of stone as was his.”[19]

In 1980, Queen’s Fort and the surrounding sixteen acres were nominated for, and placed on, the National Register of Historic Places. Photographs accompanying the application indicate that some stones had tumbled down from a straight stonewall, but it was still noticeable from where the line of the stonewall had been. In the application, the following is stated:

“In total, seven seventeenth century fortifications know to have been constructed by Native Americans exist in the region of Narragansett Bay to Long Island Sound. Rhode Island’s only authenticated fortification is Fort Ninigret in coastal Charlestown . . . . Occupied from circa 1620 to 1680, three periods of building occurred at Ninigret, culminating with the construction of a dry-laid stone wall probably surmounted by a wooden superstructure. Should archeological investigations take place at Queen’s Fort and prove successful, we would have the opportunity to obtain data on inland, post-contact aboriginal defenses which could be compared with information from Fort Ninigret . . . .”[20]

It does not appear that any major excavations have been made at the site. If there were, it might confirm that the site was occupied by Indians as well as the duration of the occupation. The landscape of large, closely-spaced boulders, however, would likely hamper any archeological efforts. All we have is Elisha Potter’s 1835 observation that arrowheads were found in the Queen’s Bed Chamber. In addition, about six test pits were dug by archeologists in the 1970s. They only found a fragment of a seventeenth century pipe bowl, which resembles one recovered at Cocumcussoc.[21]

In the nineteenth century, it was said that Queen’s Fort was inhabited for a time by horse thieves, sheep stealers, and unspecified robbers. According to Howard Chapin, a hermit “lived at the northeast corner of the fortress for several years” until “his friends removed him to a better location.”[22] This may have been the cause of J. R. Cole, in his history of Washington County, stating that the Queen’s Chamber was then “nearly filled with rubbish.”[23]

Today, there is only the barest trace of the Queen’s Chamber and it is difficult to envision the complete fort. The deterioration of the site since 1949, and even 1980, when many of the stonewalls were still visible, has accelerated. Unfortunately, no efforts were made to preserve the site.

Still, enough exists of the site in places to make it clear that it was once a stone fort. The outcroppings of the large glacial boulders and on hill top and along the hill sides are impressive. It does not take too much effort to imagine how strong a position the Queen’s Fort once was and to imagine Narragansett warriors and their families jumping from boulder to boulder.

Some visitors have recently built a small circular stone wall using small stones on one of the hills, Exeter’s version of Little Round Top at the Battle of Gettysburg in the Civil War.

Fortunately, the land occupied by the former Queen’s Fort is owned by the Rhode Island Historical Society. Hence, it is unlikely to be developed, if ever. Today, it is managed by the Department of Environmental Management, Division of Parks and Recreation. I found a reference to the state Office of Forests and Parks managing the 53-acre Queen’s Fort site as far back as 1935.[24]

I brought my wife, Margaret, to Queen’s Fort on one of our first dates, in 1982 (Block Island, it turned out, was the more romantic spot for us). There had been a road marker, allowing me to find it in 1982, but none exists now. When I tried recently to return there, I failed on three separate occasions, and even resorted to knocking on the doors of unknowing neighbors. Finally, I asked for assistance in my email alert to smallstatebighistory.com readers, and I received several helpful responses. My wife and I revisited Queen’s Fort on the weekend we celebrated our 35th anniversary.

Here are directions for finding Queen’s Fort. Driving north up Route 2 from Ten Rod Road in Exeter at the intersection of Route 4, take a left onto Stony Lane (driving south on Route 2 past Allie’s Donuts, take a right on Stony Lane). In about one-eighth of a mile driving west, you will see Narrow Lane on your right. Proceeding on Stony Lane, you will see immediately on the left two dirt roads leading into a farm; the second one used to be a common way to walk to Queen’s Fort from the north. Walking west about 200 yards from the stonewall and barn will allow one to approach the eastern side of the site. Given that the stonewall and barn appear to be on private land, I kept going, but it gave me an idea of where Queen’s Fort is located.

Driving about three hundred yards, along a highly manicured stonewall on the right, one sees an opening in the stonewall, with a black-iron grating fence guarding the opening. Just before the fence on the opposite (left) side of the road are two fairly large stones (the far one, a tan color), marking the start of the footpath into the woods. That is the entrance to the west side of Queen’s Fort. I drove on and turned my car around and was able to park nearly opposite the gate on the side of Stony Lane with my car off the road entirely. I walked between the stones on the south side of Stony Lane. After a short jaunt, there is a trail to the left that probably leads to where the Queen’s Chamber was located, but I carried on. About thirty yards from the stone entrance is a small hill. Walking up the hill, there is a dirt path around a tree. To the left of the tree is the path that can be taken to the former site of Queen’s Fort. The large boulders are strewn for long distances all around, a remarkable sight. (It is best to avoid a summer to visit due to the prevalence of mosquitos, as Margaret and I learned some 37 years ago).

The author’s brother, Shaun McBurney, inside another possible hideout at Queen’s Fort, November 25, 2018 (Christian McBurney)

Why this historic spot has been relatively ignored is not clear. Through the 1960s, Queen’s Fort was marked on maps of historic locations in the state and South County. A roadside marker erected in 1931 is missing. Most likely, the decision was made that neither the Rhode Island Historical Society nor DEM could afford to maintain and service a small park in a rural area. By removing signage, the numbers of young drinkers who might litter the place or move the locations of the stones are kept to a minimum. Today, few residents who live on Stony Lane and its environs even know where Queen’s Fort is located. Only those interested in the state’s history or natural marvels will make the effort to trek to Queen’s Fort.

[Banner image: The author stands in the Queen’s Chamber at Queen’s Fort, November 25, 2018 (Carl Pallister)]

Notes:

[1] Quoted in Marsden J. Perry, “Queen’s Fort,” Rhode Island Historical Society Collections, vol. XXIV, No. 4 (Oct. 1931), 144 (Joseph Dudley letter). [2] Eric B. Schultz and Michael J. Tougias, King Philip’s War, The History and Legacy of America’s Forgotten Conflict (Woodstock, VT: The Countryman Press, 1999), 254; Douglas Edward Leach, Flintlock and Tomahawk, New England in King Philip’s War (New York, NY: W Norton & Company, 1958), 211-12. [3] Quotations and sources are in Perry, “Queen’s Fort,” 144-45. [4] Stuart J. Goulding, “Deep in the Rhode Island Forest,” Yankee Magazine (March 1969), 44. [5] See, e.g., Donita Naylor, “A View from Exeter: A Sacred Place, Possibly from the Time of Glaciers,” Providence Journal (posted online Dec. 7, 2014). [6] Francis P. McManamon, Linda S. Cordell, Kent G. Lightfoot, and George R. Milner, Archeology in America: An Encyclopedia, vol. 1 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008), 129-30. [7] Elisha R. Potter, Jr., The Early History of Narragansett, in Collections of the Rhode-Island Historical Society, vol. III (Providence, RI: Marshall, Brown and Company, 1835), 224 (recorded in the Rhode Island land evidences for 1703 in connection with the laying out of a highway is a reference to the “stony fort,” described as on land near current Kingston and not near current Wickford) and 407 (“Stony Fort is in the back of Carr’s, east of Arnold Sherman’s. The brook there is called Fort brook. See deed from Anthony Low to Jeffrey Champlin. N. Kingstown Records.”). See also NEARA Journal, volumes 11-16, 1976 (Stony Fort is “associated with the local Indians of the 17th century. Not to be confused with Queen’s Fort in the same town. Stony Fort is supposed to exist near the North Kingstown-Exeter town line.”). Current Stony Fort Road is just north of Kingston and south of Shermantown Road. [8] Patrick M. Malone, The Skulking Way of War: Technology and Tactics Among the New England Indians (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991), __. [9] Goulding, “Deep in the Rhode Island Forest,” 44. [10] John R. Bartlett, ed. Records of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, vol. 4 (Providence, RI: Knowles, Anthony & Co., 1859), 349. [11] Elisha R. Potter, Jr., The Early History of Narragansett, in Collections of the Rhode-Island Historical Society, vol. III (Providence, RI: Marshall, Brown and Company, 1835), 84, n. [12] J. R. Cole, History of Washington and Kent Counties, Rhode Island (New York, NY: W. W. Preston & Co., 1889), 663. [13] James N. Arnold to Hazard Stevens, Dec. 2, 1898, quoted in Howard M. Chapin, “More About Queen’s Fort,” Collections of the Rhode Island Historical Society, vol. XXIV (1931), 30. [14] Sidney S. Rider to Hazard Stevens, Nov. 1898, quoted in ibid., 29. [15] Sidney S. Rider. The Lands of Rhode Island As They Were Known to Caunounicus and Miatunnomu When Roger Williams Came in 1636 (Providence, RI: Self-Published, 1904), 237-38. [16] Rhode Island, A Guide to the Smallest State (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1937), 368-69. [17] Goulding, “Deep in the Rhode Island Forest,” 44 and 46. [18] Ibid., 46. [19] Ibid., 44. [20] National Register of Historic Places Inventory, Nomination Form, Queen’s Fort, March 1980. [21] Chapin, “Queen’s Fort,” 150. [22] Cordell, et al., Archeology in America, vol. 1, 130. [23] Cole, History of Washington and Kent Counties, 663. [24] First Annual Report of the Department of Agriculture and Conservation of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations for the Year Nineteen Hundred and Thirty-Five (Providence, RI: Visitor Printing Co., 1936), 96.