World War I was a transformative moment for America. It would propel our still young nation into a world-wide conflict and require an unparalleled national mobilization of troops and supplies. Between 1914 and 1918 the Great War would become the first global war, claiming the lives of 9 million combatants and 7 million civilians. By 1918, all were asked to sacrifice for the war effort, and America would enter the war sending 4 million citizen soldiers including 350,000 men of African heritage to serve in the United States Armed Forces.

As men would serve overseas and at home throughout the war years, women also contributed to the war effort in important ways, individually and through service organizations including the YWCA and American Red Cross. African heritage women sacrificed as well, but their efforts were hard fought and continuously met with resistance as second-class citizens simply because of their race and sex.

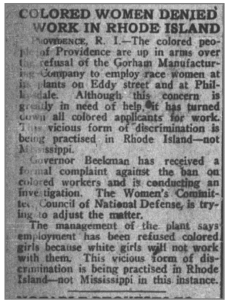

From the November 9, 1918 edition of the New York Age, the nation’s leading black newspaper of the day

In 1918, manufacturing in the US was directed toward the war, and many factories put aside the making of cars, appliances, or home goods to the manufacture of planes, tanks, and armaments for the troops. Here in Rhode Island, the Gorham Manufacturing Company, makers of silver jewelry and plate ware turned to the manufacture of war weapons such as hand grenades. The need for labor increased as the war went on, and Rhode Island women found more opportunities to enter the labor force. Nearly every day the papers carried advertisements for “Girls Wanted,” promising good pay, bonuses, attractive surroundings, and light work. What the ads did not state was “colored women” need not apply.

The New York Age, the nation’s leading black newspaper of the day, reported on November 9, 1918 that Gorham Manufacturing Company had refused to hire colored women for its Providence plants. The management of the company stated that it didn’t hire colored women because white women refused to work with them. A complaint was filed with Rhode Island Governor Beeckman and several organizations were looking into the matter. Sufficiently outraged, the New York Age reported, “This vicious form of discrimination is being practiced in Rhode Island – not Mississippi.”

Despite the challenges of discrimination faced in Rhode Island and throughout the nation, African American women would step forward to serve their community and country. Two extraordinary women of color who deserve mention are from Providence and Newport.

Born in 1867 in Providence to Henry and Amelia Jackson, Mary Elizabeth Jackson was a member of Pond Street Baptist Church and charter member of the Providence NAACP. Jackson worked tirelessly to halt discriminatory practices and improve working conditions for women of color. A statistician at Rhode Island Labor Department, during WWI she was appointed as a Special Worker for Colored Girls on the national YWCA War Work Council, analyzing employment trends and recommending programs to encourage fair employment of women of color.

As an early advocate of the rights of working women, she wrote an article in NAACP’s magazine The Crisis in November 1918 entitled, “The Colored Woman in Industry” detailing the working conditions of many of the women in factories, the many industries that they were working in, and the hopeful future of colored women in industry. She describes the working conditions of women of color in America being greatly defined by the world war stating, “Thousands and thousands of eager boys have gone to France; we all know about them. Few of us realize that at the same time an army of women is entering mills, factories and all other branches of industry.” This forward-thinking woman not only discusses the prejudice and poor working conditions these women faced, but also the inequality of wages between blacks and whites, and between men and women.

Unfair employment practices were not the only area where women of color faced exclusion or prejudice. Those who wished to support the war effort could happily do so by knitting socks, rolling bandages, and supporting troops at training camps through their social organizations such as the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, but if they wanted to volunteer in any capacity they often found that national organizations would turn them away or place them in segregated groups.

Harriet Alleyne Rice was born to George and Lucinda Rice in 1866 in Newport. She was a top student at Newport’s Rogers High School and won first prize for Greek Studies at her graduation exercises, but because the terms of the prize required that it go to a male pupil, she was denied. After high school graduation, she became the first African American student to graduate from Wellesley College in 1887, then continued her education by earning medical degrees from the University of Michigan Medical School and the Women’s Medical College of the New York Infirmary for Women and Children. Being a highly educated woman and African American during the late 19th century, she found it nearly impossible to work at any American hospital, so Dr. Rice joined famed social worker Jane Addams and the Hull House in Chicago to provide medical treatment to poor families.

When World War I broke out, Dr. Rice decided she must offer her services as a medical doctor to support the troops. However, when she attempted to join the American Red Cross, she was denied admittance as a doctor because of her race. Undeterred, Dr. Rice contacted the French government, who gladly accepted all offers of medical help. Harriet Rice served in French hospitals treating wounded soldiers from January 1915 until just a few days after the Armistice in November 1918. In 1919, the French Government awarded her the Médaille de la Reconnaissance Française, or Medal of French Gratitude, for her treatment of wounded troops.

Dr. Rice’s extraordinary but continuously frustrating life as a talented woman of color during a time of great challenges for all African Americans is best summed up with her response to a 1937 alumnae questionnaire from Wellesley College that asked, “Have you any handicap, physical or other which has been a determining factor in your professional activity?” Her reply was direct and representative of all persons of color who dared to achieve and succeed during turn of the 20th century America stating, “Yes! I am colored which is worse than any crime in this God blessed Christian country. My country tis of thee.”

Between 2014 and 2018 there will be world-wide commemorations recognizing the Centennial of the Great War between 1914 and 1918. Over these next few years, there will be much attention given to many aspects of the war from battlefields to home fronts, and here in Rhode Island we have the opportunity to recognize our own unique participation. The more we learn of the trials and accomplishments of women of color like Mary E. Jackson and Dr. Harriet A. Rice, the more we learn the complicated, but complete history of ourselves, community and nation.

[Banner Image: White women at a Gorham Manufacturing plan in Providence immersing bouchon assemblies for hand grenades in chemicals to prevent rust during World War I. Gorham refused to hire African American women at its plants. (Library of Congress)]

Bibliography

Paul Finkelman, ed. Encyclopedia of African American History: 1896 to the Present. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Mary E. Jackson: “The Colored Woman in Industry.” The Crisis, Vol. 17, No. 1, November, 1918.

Mary Korr: “100 Years Ago – Dr. Harriet Alleyne Rice of Newport: The Struggles of an African-American Physician.” Rhode Island Medical Journal, January 2015.

Newport Daily News, May 27, 1958. Obituary.

Rima Lunin Schultz and Adele Hast, eds.: Women Building Chicago 1790-1990: A Biographical Dictionary. Indiana University Press, 2001.

Emmett J. Scott: Special Assistant to the Secretary of War: The American Negro in the World War. Underwood & Underwood, 1919.

Richard Youngken: African Americans in Newport. Newport Historical Society Publications, 1998.