Note from the author: This article is a slightly edited reproduction of my September 2019 welcoming address to the National Conference of the American Speakers of the House held in Newport and hosted by Rhode Island House Speaker Nicholas Mattiello. This article will be presented here in two parts (this is Part I). It is also available as an attractive pamphlet from the Rhode Island Publications Society (at www.ripublications.org.]

Rhode Island gets little or no respect for its role in the development of the United States. Not only are its founding exploits omitted from American history textbooks, but most modern references to it are unflattering: the media often describes disaster areas affected by forest fires, melting ice packs, oil spills, and storm damage as “about the size of Rhode Island” (a tiny 1214 square miles).

House Speaker Nicholas Mattiello asked me to correct that slight: “Show my colleagues,” he said, “that Rhode Island is more than just a pretty place.” With that exhortation, I gave a welcoming address to the American Speakers of the House, “not to bury Rhode Island, as American historians and their textbooks have done, but to praise it.”

Since 1981, my wife Gail and I have toured all 50 states and traveled up and down through the lower 48, visiting many of their historic sites and physical landmarks. With Gail as navigator, we learned the rudiments of local history and geography for every state. We concluded that each has been endowed with unique, notable history and with stunning scenic beauty. My remarks, therefore, are intended not to diminish our sister states, but simply to make its leaders cognizant of tiny Rhode Island’s huge contributions to the formation of the United States.

I accomplished that task by examining eight major themes: (1) Religious Liberty and Separation of Church and State; (2) Democracy; (3) Federalism; (4) Independence; (5) the Founding of the United States Navy; (6) the Constitution; (7) American Expansion; and (8) the Birth of America’s Industrial Revolution. All were launched here by 1790, the year Rhode Island ratified the Constitution and joined the American Union.

Theme #1 Religious Liberty and Separation of Church and State

America’s two great contributions to world order and governance are a written

constitution as the national basic law and a nation founded upon religious liberty and separation of church and state.

Rhode Island, because of its boycott of the Constitutional Convention of 1787, made no direct contribution to the original document drafted by our Founding Fathers, although its indirect influence was substantial, especially in the areas of democracy, federalism, and state sovereignty.

The second great contribution, religious liberty and separation of church and state, owes far more to Rhode Island, a tiny colony of religious outcasts and dissenters, than to any other American colony or state. That contribution was in Rhode Island’s DNA. It existed from the moment in 1636 that its founder Roger Williams settled Providence—a place he named because God’s Divine Providence gave him safe refuge from the intolerant religious leaders of Massachusetts who had banished him into the winter wilderness.

Today, when most Americans living west of the Connecticut River hear the name Roger Williams, they think of the talented Omaha-born concert pianist, Louis Jacob Weertz, who used Roger Williams as his stage name.

Rhode Island’s Roger Williams was not a musician, but (to use a musical metaphor) he marched to a different drum and used the Bible as his instrument. Williams, a graduate of Cambridge College, was a Biblical scholar. His peculiar and uncommon method of Biblical interpretation is key to his beliefs regarding religious freedom, or “soul liberty” as he called it, and his erection of a “wall of separation” between church and state—or, as he phrased it, “the garden of the church and the wilderness of the [secular] world.”

Roger Williams, in the winter of 1635-1636, was banished from Massachusetts and into the wilderness, where he was sheltered by the Wampanoag Tribe. Later, the Narragansett Tribe deeded him land for his settlement of outcasts. Sketch by C. W. Jeffreys (Pageant of America, vol. 1)

Williams sought this separation not to protect the state from religion, but rather to protect religious belief from the coercion of the state. As a passionately religious man and ardent Biblicist, he sought to establish a state based upon freedom for religion, not freedom from religion.

Williams, who arrived in America in 1631, was banished from Puritan Massachusetts, after earlier ejection from Plymouth Colony, because he preached against the cornerstones of Puritan belief and practice, particularly their theology of the covenant based upon the Old Testament in which civil magistrates enforced theological belief. Williams subscribed to a typological method of Biblical interpretation whereby he considered the Old Testament metaphorical rather than literal and historical. The alleged use of government by the ancient Israelites to enforce religious orthodoxy was repudiated, said Williams, by the New Testament’s exaltation of “soul liberty” whereby the individual conscience was free from state interference or coercion. Christ, said Williams, had decreed a separation between the divine and the secular between the spirit and the flesh.

What is important is not how Williams arrived at his position through very complex Bible study, but rather the consequences of his belief. Those initial consequences were the Providence town compact of 1637 limiting government “only to civil things” and a plantation agreement in 1640 with the same restriction. By his example, Williams attracted other banished dissenters from Massachusetts such as Anne Hutchinson, co-foundress of the town of Portsmouth in 1638, leader of a religious sect called the Antinomians, mother of fourteen children, and America’s first great female leader.

Soul liberty also lured Baptist minister Dr. John Clarke, who settled Newport in 1639 with William Coddington, and Samuel Gorton, a freethinking man with a passion for disputation, who established Warwick in 1643 as Rhode Island’s fourth town. In 1638/39, Williams helped found America’s First Baptist Church in Providence; then Clarke formed the nation’s second Baptist Church in Newport sometime in 1641. (The split dates result from the fact that Protestant England retained the Julian Calendar until 1752. By that “old style” calendar, New Year’s Day was March 25 rather than January 1.)

Dr. John Clarke, the leading Newport Baptist, secured Rhode Island’s famed King Charles Charter of 1663 and crafted its liberal religious provisions.. His role in the establishment of religious freedom in America deserves greater recognition.

All of these Rhode Island pioneers were refugees from and victims of the dogmatic effort by the religious leaders of Massachusetts to establish and secure what evolved into a moderate Congregationalism.

Because the Puritans and Pilgrims were horrified by the existence in their midst of what they later would describe as a “moral sewer,” they therefore formed a New England Confederation in 1643, whereby the colonies of Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, Connecticut, and New Haven not only combined to surround the Narragansett Bay settlements, but also moved to absorb them.

To preserve the lands that he had purchased from the Native Americans on his own behalf and for fellow dissenters, Roger Williams journeyed to England in 1643/44 and secured from a cooperative Parliament a patent tacitly admitting that those Indian deeds were valid and also confirming the right of Rhode Island’s outcasts to the land they occupied. The patent repeated the oft-used phrase “only in civil things” to limit the power of the colonial government that Parliament had recognized.

News of the establishment of Rhode Island as a refuge for oppressed religious minorities soon spread across the Atlantic world. In 1657 a contingent of persecuted English Quakers arrived in Newport where they established a meetinghouse. In 1658, fifteen Sephardic Jewish families arrived in Newport as refugees from the Spanish Inquisition. They had traveled to Rhode Island via Brazil and then New Amsterdam. Those of the Jewish faith who later came to Newport would establish in 1763 Touro Synagogue, now America’s oldest Jewish house of worship.

Rhode Island’s Parliamentary Patent of 1643/44 remained the basis of the colony’s government until the Stuart dynasty was restored to the English throne in 1660. The Restoration rendered doubtful the legal validity of the patent and placed Rhode Island in a precarious position because of her close ties with the anti-monarchical Commonwealth and Protectorate of Oliver Cromwell. That faction had gained power in the 1640s and beheaded King Charles I, father of the newly restored king.

The apprehensive colony, fearful for its legal life, commissioned the able and diligent Dr. John Clarke as its agent to obtain royal reaffirmation of its right to exist. In his 1652 treatise Ill Newes from New England, Clarke had espoused principles of religious liberty similar to those of Williams.

After an exasperating delay stemming from conflicting claims of Rhode Island and Connecticut to the Narragansett Country (i.e., the southern Rhode Island mainland), Clarke, with the assistance of Connecticut’s agent John Winthrop, Jr., secured from Charles II the Royal Charter of 1663. This coveted document, using some revolutionary language crafted by Clarke, was immediately transported to Rhode Island, where it was unanimously received by the grateful colonists in November 1663.

The charter’s most liberal and generous provision bestowed upon the inhabitants of the tiny colony “full liberty in religious concernments.” The document commanded that

Noe person within the sayd colonye, at any time hereafter, shall bee any wise

molested, punished, disquieted, or called in question, for any differences in

opinione in matters of religion, and doe not actually disturb the civill peace of

our sayd colony; but that all and everye person and persons may, from tyme to tyme,

and at all tymes hereafter, freelye and fullye have and enjoye his and theire owne

judgments and consciences, in matters of religious concernments, throughout the

tract of lande hereafter mentioned; they behaving themselves peaceablie and

quietlie, and not useing this libertie to lycentiousnesse and profanenesse, nor

to the civill injurye or outward disturbeance of others; any lawe, statute, or clause,

therein contayned, or to bee contayned, usage or custome of this realme, to the contrary hereof, in any wise, not withstanding.

This guarantee of absolute religious liberty vindicated Williams’s beliefs and royal recognition of the fundamental principles upon which the Providence Plantation was founded: absolute freedom of conscience and complete separation of church and state. As Williams observed, this liberality stemmed from the king’s willingness to “experiment” in order to ascertain “whether civil government could consist with such liberty of conscience.” This was the “lively experiment” on which the government of Rhode Island was based.

King Charles II, called the “merry monarch,” deserves great credit for participating in this revolutionary experiment. His tolerant nature probably stemmed from his father’s persecution by the Puritans for his high Anglican stance and his wife Catherine of Braganza’s Catholic faith and Portuguese birth.

Williams’ pioneering achievement in founding a colony based on complete religious liberty is notable not only because it defied the conditions existing in the immediately adjacent colonies, but also because it ran counter to the current religious climate throughout Christendom. Williams made his experiment in the midst of the Thirty Years’ War, a great struggle on the European continent with deeply religious overtones that left 8 million people dead from battle, famine, or disease. When the Treaties of Westphalia ended this bloody struggle in 1648, a religious settlement was reached, reaffirming the principle of cuius regio; eius religio, which translated means “whose realm; his religion.” Each of the many princes or rulers involved could then determine the religion of his own state: Catholic, Lutheran, or Calvinist. The Peace of Augsburg, a settlement in 1555 following an earlier religious war, limited this principle to Catholics and Lutherans only.

Williams strongly denounced the ubiquitous forcible coercion of the human conscience. In 1644, he published The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution for the Cause of Conscience, followed in 1652 by The Bloudy Tenent, Yet More Bloudy. In these writings, Williams contended that throughout history forced worship had been the major cause of persecution and bloody religious warfare. He observed, in his typical pungent style, that “forced worship stinks in God’s nostrils” and that the use of force to control another’s conscience was “rape of the soul.”

King Charles II was so moved by Dr. John Clarke’s entreaties that he replicated the language of the Rhode Island charter in the 1663 charter he gave to Lord Anthony Ashley Cooper and his seven associates for the proprietary colony of Carolina (not divided into north and south until 1729). In 1665, the first two (of many) New Jersey proprietors, Lord John Berkeley and Sir George Carteret, also repeated the language of Rhode Island’s basic law in their founding agreement. Unfortunately, Carolina’s freedom was diluted by the establishment of the Anglican Church, and New Jersey’s was impaired by a succession of different proprietors and by political instability until it became a royal colony in 1702.

However, Pennsylvania and its Quaker founder, William Penn, who had corresponded with Roger Williams, came closest to replicating the Rhode Island ideal. In 1681, Charles II made Penn a colonial proprietor in gratitude for service to the Crown rendered by Penn’s father, an admiral in the Royal Navy. Charles also allowed Penn to conduct a “holy experiment” in religious liberty.

Pennsylvania, which never faced a serious charge of religious persecution, joined Rhode Island in offering its inhabitants the greatest degree of religious liberty in colonial America. Of the thirteen colonies, only four—Rhode Island, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and its 1704 offshoot Delaware—refrained from creating an established church.

The first line of our federal Bill of Rights reads “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” Historians, lawyers, and religious scholars have debated the origins of this momentous clause. The consensus is that it derives chiefly from two parallel, but sometimes incongruous, positions: the Rhode Island dissenting tradition with its Biblical base devised by Roger Williams and carried forward by Baptist preachers, most notably New Englander Isaac Backus (1724-1806), a contemporary of the Founding Fathers; and the 18th century Enlightenment tradition rooted in natural law and natural rights as expounded by Englishmen John Locke, Algernon Sidney, and several Whig libertarian writers, who held that common sense and free choice rather than coercion should govern one’s religious and intellectual views. This position was embraced by learned Americans, most notably Virginians George Mason, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison, principal author of the Bill of Rights.

One need recall, however, that the successful step in disestablishing the Anglican Church in Virginia was Jefferson’s Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom. It passed in 1786 with pressure from and the support of Virginia’s Baptist community. By that time, Rhode Island had been enjoying soul liberty and complete separation for 150 years! It was surely a seasoned model upon which to base the First Amendment.

Theme #2 Democracy

There were two distinct forms of colonial government in America: the corporation and the province. Provinces were of two types, proprietary and royal, but in both, power proceeded from above downward because the source of authority lay outside the province, either with the proprietor or the king. The corporate colony was more democratic and self-governing, for its power rested upon members of the corporation, who were also freemen of the colony. Only Massachusetts (until 1691), Connecticut, and Rhode Island became legally recognized corporations and thus self-sufficing political units. However, both Massachusetts and Connecticut maintained established Congregational Churches, a religious connection that influenced and shaped governmental policies, especially in Massachusetts. In Rhode Island, with no established church and very little outside control, politics was both democratic and free-wheeling. By the time of the American Revolution, there were two corporate colonies and three proprietorships: Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Maryland. The other eight colonies were royal.

Rhode Island’s 6,500-word corporate instrument devoted relatively brief space to organization of government, but it did provide for the offices of governor and deputy governor, as well as ten assistants. The original holders of these positions were named in the charter itself, but their successors were “to be from time to time, constituted, elected, and chosen at-large out of the freemen” of the colony, or “company,” on an annual basis. The charter also provided that certain “of the freemen” should be “elected or deputed” by a majority vote of fellow freemen in their respective towns to “consult,” “advise,” and “determine” the affairs of the colony in connection with the governor, deputy governor, and assistants. These town representatives would be elected semi-annually. The charter specified that Newport was entitled to six of these “elected or deputed” representatives; Providence, Portsmouth, and Warwick received four each; and two were to be granted to any town established in the future. This apportionment was equitable in 1663 and for a century thereafter, but its inflexibility would become a source of grave discontent in the 19th century, as evidenced by the Dorr Rebellion.

The governor, deputy governor, assistants, and representatives or deputies were collectively called the “General Assembly.” Each member of this body had one vote. The Assembly, with the governor presiding, was to meet at least twice annually in May and October. The only charter-imposed qualification for members was that they be freemen of the colony.

Rhode Island’s legislature was endowed by the charter with extraordinary power. It could make or repeal any law, if such action was not “repugnant” to the laws of England; set or alter the time and place of its meeting; and grant commissions. It could exercise extensive powers over the judicial affairs of the colony, prescribe punishments for legal offenses, grant pardons, regulate elections, create and incorporate additional towns, and “choose, nominate and appoint such . . . persons as they shall think fit” to hold the status of freemen.

The royal charter also provided for the raising and governing of a militia, conferred rights of fishery along the coast of New England, encouraged immigration to the colony, and established acceptable boundaries (which included the Pawcatuck River as the western line of demarcation). In 1696, the General Assembly chose to become bicameral, with the town deputies constituting the so-called “lower house.”

That free-wheeling nature of Rhode Island politics emerged full-blown in the 1750s with the formation of two sectional factions: one led by Stephen Hopkins with supporters drawn mainly from Providence County; the other led by Samuel Ward of Westerly, whose supporters came from the southern Rhode Island mainland and Newport. Professor Jackson Turner Main, the most authoritative historian of the American party system, asserts that the Ward–Hopkins battle for control of the powerful General Assembly marks the beginning of the two-party political system in America.

Stephen Hopkins, leader of a political faction centered in Providence, served as governor of Rhode Island numerous times and held many other colony offices before signing the Declaration of Independence in 1776 (Brown University Portrait Collection)

Although the governor lacked significant constitutional power—a condition that prevailed in Rhode Island until the enactment of separation of powers amendments to our state constitution in 2004—by the power of personality and intellect, some governors transcended that legal limitation. Stephen Hopkins was one such governor, holding the post for nine annual non-successive terms, as compared with only three for Ward. Hopkins was also appointed chief justice for eleven annual terms, compared with one year for Ward. In addition, Hopkins also held Rhode Island’s most powerful political position—Speaker of the House—for seven six-month terms.

One humorous episode in this battle for General Assembly control occurred in 1757. With the power to establish new towns—one of its nearly unlimited prerogatives—the legislators cut Ward’s 79-square-mile town of Westerly in two, creating a new town from its northern 44 square miles. The Assembly named the new municipality Hopkinton! This political ploy gave the Ward faction two more seats in the lower house, but, apparently, the Hopkins party felt that the satisfaction was worth the sacrifice.

During the resistance of 1760s and early 1770s leading to the War for Independence, democratic Rhode Island repeatedly vexed the Crown and British officials by its defiance and its determination to maintain the system of self-government it had enjoyed for over a century.

English observers commented with disdain concerning the Rhode Island system of self-government. After his famous travels through the American colonies in 1759–60, the articulate Rev. Andrew Burnaby wrote that, especially in Rhode Island, “men in power are dependent upon the people.” When investigating the burning of the Gaspee (discussed below), Chief Justice Daniel Horsmanden of New York pejoratively described Rhode Island as a “downright democracy,” and Thomas Hutchinson, harried royal governor of Massachusetts, told King George III that “Rhode Island is the nearest to democracy of any of your colonies.”

The people of Rhode Island did indeed keep careful watch on their representatives—not only by annual elections for general officers and the upper house and semi-annual contests for representatives, but also by having a General Assembly that rotated among the colony’s five counties. These counties were created by the General Assembly between 1703 and 1750. Their statehouses have all been beautifully preserved. The oldest and largest of these citadels of government is the Newport Colony House, built between 1739 and 1743. This practice of rotating legislative sessions, which I have called “traveling in political circles,” continued until 1854, long after Rhode Island achieved statehood. Until 1900, there were still two capitals: Newport and Providence. This system made the government very close to the people in every way.

This extreme democratic localism based upon the town meeting led Rhode Island to resist the centralizing tendencies of the Founding Fathers in 1787, prompting the latter to call Rhode Island “Rogues’ Island”—a place characterized by “democracy run rampant.”

America’s greatest 19th century historian, George Bancroft, a long-time Newport summer colonist, wrote a detailed 10-volume history of the United States covering the period from the founding through the 18th century. In volume II, page 64, he exclaimed (with only a modicum of hyperbole) that “nowhere in the world were life, liberty and property safer than in Rhode Island.” Bancroft was no myopic scholar. He was an ardent, active supporter of Andrew Jackson and his democratic movement. Jackson’s protégé, President James Knox Polk, appointed Bancroft his Secretary of Navy. In that position Bancroft became the principal founder of the U.S. Naval Academy. He later served as U.S. minister to England and then to Germany.

Oddly, given the obvious and overwhelming significance of Rhode Island’s Royal Charter of 1663, this founding document is often ignored. Back in the late 1950s, as a student at Providence College, I took a course entitled Documents of American History; the textbook was a thick tome by the same name edited by the noted American historian Henry Steele Commager. From 1938 to 1988, that reference book went through ten editions in which 700 key American documents were printed, either in their entirety or just that part with the greatest significance. I looked in vain for the charter. Even with my limited knowledge then of Rhode Island’s past, I was bewildered by this omission.

The Annals of America is a huge compilation of our nation’s major documents and, according to its editors from Encyclopedia Britannica, contains “almost every kind of American writing.” Though the editors of this 20-volume, 2,364-item set assert that it contains “all of the documents that are essential to a full understanding of the ‘official’ history of the United States,” the path-breaking phrases of the Rhode Island Royal Charter of 1663 are not included. Evidently religious liberty, separation of church and state, and participatory democracy were deemed non-essential. No respect is bad; disrespect is worse.

Theme #3 Federalism

In 1763, at the end of the Great War for Empire—a four-phase conflict resulting in a victory for England over France in the struggle for North America—England decided to exercise much greater administrative control over her American colonies. This decision stemmed in part from a desire to ensure that the colonies paid their fair share of costs for that long conflict that had begun in 1689.

The first revenue measures enacted by England were the Sugar Act of 1764 and the Stamp Act of 1765. The colonists promptly objected for a variety of reasons. The Sugar Tax was especially onerous in Rhode Island because it burdened Rhode Island’s lucrative molasses trade with the West Indies and hampered local production of rum.

The Stamp Act, which imposed a tax on circulating paper items such as licenses, newspapers, and legal documents, was a novel internal tax rather than an external one on trade. It brought wider opposition. Dissenting colonies, led by Massachusetts, called a Stamp Act Congress, which met in New York City in October 1765, with Rhode Island and eight other colonies attending. The delegates drafted a protest and petitions, asserting that an internal levy was “taxation without representation” because the colonies did not have members in the British Parliament. Colonial leaders such as James Otis, Daniel Delaney, Patrick Henry, and John Dickenson wrote essays denouncing the levy, stating that “taxation without representation is tyranny.” Rhode Island went much further. It engaged in random acts of vandalism and civil disobedience. Rioters in Newport tarred and feathered John Robinson, the local stamp collector, and they assaulted Augustus Johnston, the stamp distributor.

Fortunately, cooler heads prevailed on both sides of the Atlantic. England repealed the Stamp Act in 1766 but simultaneously passed the face-saving Declaratory Act, asserting that Parliament by legislation can “bind the colonies in all matters whatsoever.”

In this initial united colonial confrontation with the Mother Country, Rhode Islanders did more than tar and feather—especially Stephen Hopkins and Silas Downer of Providence.

In 1765, Hopkins promptly responded to England’s imperial reorganization plan by publishing an influential treatise entitled The Rights of Colonies Examined. It not only denied the power of Parliament to levy a direct tax on the colonies without their consent, but also proclaimed a federal conception of the British Empire whereby the colonies were sovereign in matters of local concern subject only to the king. In 1766, Hopkins’ essay was republished in London.

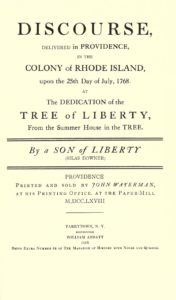

In 1768, Silas Downer, a colleague of Hopkins, delivered an oration at the dedication of a Providence Liberty Tree that he subsequently published. According to Professor Carl Bridenbaugh, Downer’s biographer and a leading historian of colonial America, “Silas Downer forthrightly denied the authority of Parliament to make laws of any kind to regulate the colonies a full six years before any other patriot dared to enunciate this doctrine in public.” By 1774, Thomas Jefferson became that “other patriot.” Downer’s view anticipated the dominion theory of empire.

John Dickinson of Pennsylvania and Delaware joined the Rhode Island duo Hopkins and Downer in developing a theory of federalism. Dickinson, justly styled “the Penman of the Revolution,” wrote his Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania in 1768 to oppose the Townsend Acts, the second wave of taxes on the colonies. This work also espoused the notion of a federal empire.

Cover page of pamphlet published in Providence, in 1768, on the dedication of the “Tree of Liberty” by a “Son of Liberty” in Providence, by Silas Downer

Hopkins and Downer both died in 1785, but Dickinson, the principal draftsman of the Articles of Confederation, was present at the Constitutional Convention of 1787, where he championed the creation of a government based on federalism and state sovereignty. Having contributed to its formulation, Rhode Island’s leaders demanded such a system in return for this state’s grudging ratification of the Constitution.

Theme #4 Independence

The final steps towards American independence and the war with England to secure that independence began in 1772. The roles of Massachusetts and Virginia in the leadership of this movement are well known. However, Rhode Island also belongs on the front line.

Prior to June 9, 1772, nearly every colony expressed opposition to England’s imperial reorganization with petitions, resolutions, and defiant, but petty, acts of vandalism. Rhode Island joined that crowd. In July 1764, a colonial gunner at Fort George, here on Goat Island, fired a warning shot over the bow of the St. John, a British customs schooner attempting to enforce the Sugar Act. In June 1765, Newporters stole a small tender from the British customs frigate Maidstone and burned it. During that same year, Newporters rioted and assaulted the Stamp Act officials. In July 1769, Newporters seized and burned the schooner Liberty that customs officials had seized from prominent Boston merchant John Hancock.

Amid these physical acts of defiance, Providence leaders Stephen Hopkins and Silas Downer defied Parliament by publishing pamphlets promoting the federal theory of empire.

On June 9, 1772, these annoying actions were eclipsed by what Rhode Islanders call (correctly) “the first blow for freedom.” On that evening, eight 12-man longboats led by Abraham Whipple rowed from Providence and another came from Bristol to attack an armed customs schooner named the Gaspee. That ship had run aground on a sand bar off the shore of the town of Warwick, about 6 miles south of Providence. There Gaspee raiders seized the English naval vessel; shot its commander, William Dudingston, in the groin when he attempted to resist; removed the crew; and burned the vessel to the waterline. The fact that the raiders took Lieutenant Dudingston to a local doctor for treatment did not diminish the rage of English officials when they learned of this daring attack on His Majesty’s Navy.

In August 1772, the king issued a proclamation denouncing the outrage, created an investigatory commission, and offered a £500 reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the perpetrators. Later the reward was increased to £1000.

Beginning in January 1773, the royal Gaspee commission held hearings. Despite the huge reward for information regarding a rebel force of approximately one hundred men, no Gaspee raider was conclusively identified or charged. The commission adjourned reluctantly on June 22, 1773.

But as famous radio commentator Paul Harvey would say: “Now for the rest of the story!” The royal commissioners had been instructed to send any identified perpetrators to London for trial, clearly violating a basic right of English citizenship—the right to a fair trial in the vicinage, the place where the alleged crime occurred. (If one regards this as a minor concern, look no farther than present-day Hong Kong and its riots over extradition to China.)

Incumbent Rhode Island Chief Justice Stephen Hopkins was alarmed and wrote letters concerning this threat to friendly legislators in other colonies. He proposed to them the establishment of formal committees of correspondence to deal in unison with such violations of American rights. Virginia replied by establishing a legislative committee of correspondence. The other colonies followed suit.

Then, in December 1773, a band of Massachusetts rebels dressed as Indians and led by firebrand Sam Adams protested the Tea Act by boarding three British East India Company merchant vessels in Boston Harbor and dumping 340 casks of tea into the water. This so-called Boston Tea Party—far more famous, but far less bold than the burning of the Gaspee—led England to pass four Coercive Acts to punish Massachusetts for this act of resistance. The Americans called the laws “Intolerable.”

Historians have often stated that these acts led to the call of the First Continental Congress, the first united step towards war and independence. However, consider this sequence: (1) the four acts were passed separately from March 31 (the Boston Port Bill) to June 2 (the Quartering Act); and (2) the first call for the Continental Congress came from the Providence Town Meeting on May 17, 1774. When Pennsylvania and New York responded promptly and positively, the Rhode Island General Assembly made the colony the first to appoint delegates. On June 15, 1774, Stephen Hopkins and his political nemesis Sam Ward were dispatched to Philadelphia. When Rhode Island initiated the call on May 17, only the passage of the least obnoxious measure, the Boston Port Bill, was known in America.

William Ellery of Newport arrived in Philadelphia in time to sign the Declaration of Independence and replace as a delegate to the Continental Congress Samuel Ward of Westerly, who had died of smallpox (New York Public Library Digital Collections)

On March 2, 1775, Providence had its own tea party by burning 300 pounds of that valuable leaf in its Market Square. Then on May 4, 1776, Rhode Island became the first colony to formally renounce allegiance to King George III—an act we now celebrate (with a little hyperbole) as Rhode Island Independence Day.

In view of this scenario, Virginia and Massachusetts should share the spotlight with Rhode Island as the leaders in the campaign to create a new nation!

[Banner image: “Roger Williams bring the Charter—1644” (New York Public Library Digital Collections)]