Providence was ready to experiment with a new form of transportation at the end of the Civil War, a means of travel popularized in several other Metropolitan areas. New York City was host to the first horsecar on rails in the United States in 1832 as it had been for the first omnibus a year earlier. Horsecars did not catch up elsewhere until the 1850s. By 1886, however, there were 525 “animal” railways scattered among some 300 American municipalities.

The Rhode Island general assembly passed legislation on March 14 1861 to incorporate Rhode Island’s first horsecar lines. Three acts permitted the formation of the Providence, Pawtucket and Central Fails Railroad Company; the Broadway and Providence Railroad Company; and the Providence and Olneyville Railroad Company. These initial incorporations signaled a jockeying for profitable routes rather than a rush to immediate construction. Almost three years passed before the first horsecar carried a paying passenger.

The omnibus in the background once had a monopoly on service to the Blackstone Boulevard on Providence’s East Side. Horsecars, using rail lines, began service in 1876. The two forms of transportation clashed in a race in which the railed, upstart horsecar was destined to win (Courtesy of Bob Bennet)

The backers of these lines, according to Union Railroad Executive Secretary, Henry V. A. Joslin, were “men of capital interests in the section of the city or suburban district which the particular road was designed to benefit.” These early investors were landowners who believed that faster transportation would entice interested homebuilders to their suburban holdings. The initial vagaries of the Civil War probably dampened interest but as the war turned in the Union’s favor real estate fever returned.

The incorporators of the Providence, Pawtucket and Central Falls Railroad met at the home of Adam Anthony in North Providence on May 11, 1863 to raise the necessary funds. Most of the $100,000 capital stock was pledged that day. The interested parties, mostly landowners in the North Providence and Pawtucket area, elected Hiram H. Thomas, president. Thomas was the editor of the Providence Evening Press.

Prior to this time, local investors may have hesitated to finance railway construction due to a particular ordinance. Providence polled voters to authorize steam railroads and, by implication, horse railways, to lay tracks “upon and over or along any of the public highways.” Horsecar entrepreneurs probably paused after an incident almost a year earlier in 1862 when voters rejected a request by the Hartford, Providence and Fishkill (steam) Railroad to lay a mile of track from wharves at India Point to the Sabin Street depot. Citizens opposed disfigurement of city streets and danger to life and limb. One letter to the editor complained that the railroad would transform Dorrance Street into “another coal and lumberyard.”

Another undiscussed reason for local opposition to street rails was the raised nature of the “gutter track.” This type of rail, common in most American cities in the 1850s, protruded above the street surface and damaged wagon wheels and axles. These conditions particularly upset affluent owners of private carriages. ,Sponsors of the Providence to Pawtucket horsecar line understood local sentiment even though no one was likely to confuse a single horsecar carrying passengers with a freight train on city streets. Hiram Thomas used the columns of his influential Providence Evening Press to soothe hostilities and build support for the venture before submitting the question to vote.

The referendum coincided with the general election on May 13, 1863. The ballot explained that the carrier was “a horse railroad company” and not a steam line. Thomas wrote in his newspaper that “The substitution of what is known as the Philadelphia flat rail, for the obnoxious patterns first used, has wrought an important change in the practical operation of street railroads, and won to their warm advocacy many who violently opposed them. It is this improved rail which will be laid down here.” A wood pattern of the proposed flat track was on display at all ward rooms the day of the election. Thomas editorialized that the horse railroad would “open up for building purposes a large track fitted for the residence of classes who are more than willing to reside at some distance beyond the thickly settled portion of the city, if they can go to and from their place of business without too much loss of time and at a light expense.” The Providence Journal wrote, “Horse railroads have been constructed in most of the large cities; and with great success, everywhere promoting the public convenience, increasing business and raising the value of property.” The measure passed in all city wards, 1,022 to 300.

Mount Pleasant horsecar #253 photographed on Academy Avenue in Providence about 1890 (Collection of R. L. Wonson)

Survey crews and track gangs positioned tracks into place by April 1864. The owners refurbished a stable on Mill Street in Pawtucket and purchased 90 horses and 10 cars but “the roughness of the rails” prohibited passenger traffic until glitches were corrected. No secondary source has ever provided a specific date for the inauguration of horsecar service in Rhode Island. Too many false starts, lost trips and last-minute postponements prevented historians from establishing a firm date. Most accounts simply assign a month March, April, or May, 1864, as the beginning of true revenue service. The Catholic Ladies of Pawtucket, a benevolent association, planned a “Grand Inauguration Fair” to mark the opening and the Van Amburgh circus scheduled a visit to coincide with the kickoff. But the roughness of the rails persisted. Hiram Thomas apologized for “the difficulty of keeping the cars on the track” and announced that service would definitely start on May 25, 1864. Continued problems delayed it yet another day. Finally the pioneering horsecar line collected fares on Thursday, May 26, 1864. Real mass transit had come to Rhode Island.

Horsecars left Weybosset Bridge at Market Square in Providence and trotted through Canal, Smith, Charles, Randall and North Main Streets, across the Pawtucket city line byway of the old turnpike, and into Pawtucket on Pine and Main Streets. The tracks followed the route of stagecoaches, omnibuses and Indian couriers before them. Thirty minute service and ten cent fares, two cents less than the omnibus, pleased the public. The Pawtucket Gazette reported that “All with whom we have conversed on the subject are much pleased with riding in the cars where the track is straight and unbroken by turnouts.” The four and a half mile trip took forty five minutes and horsecars ran every fifteen minutes. An omnibus transferred passengers from downtown Pawtucket to Central Falls on a regular schedule. Drivers and conductors were “so busy that time for rest or refreshments could not be found,” especially on Sundays when most citizens enjoyed outings. Such heavy patronage that first month of operation almost precipitated a strike among the employees because of the “severity of their duties” but the company conceded more liberal working conditions.

Other railway entrepreneurs quickly joined the ranks of horsecar enthusiasts. “The success and popularity of the Pawtucket line,” according to the Journal, “opened the eyes of enterprising men in all parts of the city. During the spring of ’64 there was horsecar talk on every side.” Voters approved two lines to Olneyville, one by Broadway, the other by Westminster Street. The general assembly incorporated four more horse railroads the same year. The South Main Street Horse Railroad Company served Providence’s East Side and East Providence. The Providence and Pawtuxet Horse Railroad Company connected with Cranston and Warwick by way of South Providence and Broad Street. Providence and Cranston Railroad Company, owned by the influential Sprague Brothers, connected their Cranston Print Works with Providence wharves. And Elmwood Horse Railroad Company served the wealthy and growing suburb between Trinity and what is now Columbus Square.

In this view of Olneyville Square in Providence, looking east, horsecar rail tracks weave their way through the mud. The pump on the left just in the street no doubt slaked many a horse’s thirst (Collection of R. L. Wonson)

Albert Gallup, the would-be proprietor of the Elmwood Avenue horsecar line, owned the Elmwood Omnibus Company, which received a-charter in 1855. Gallup had unsuccessfully tried to exploit the popularity of the Elmwood neighborhood and his monopoly on public transportation there by raising omnibus fares from six to ten cents. When patrons balked, he diplomatically cut the cost to a nickel and then sought a horsecar franchise. The Providence Daily Post remarked on the momentous changes in mass transit: “To those of us who remember when there was no omnibus in Providence, the idea of a thorough system of street railways is something startling.”

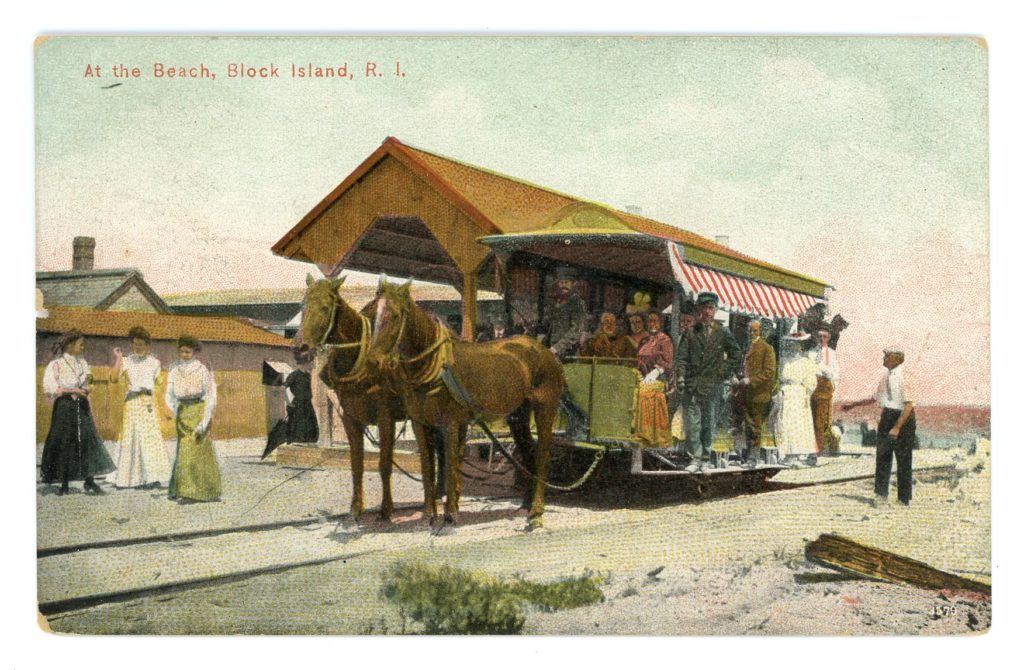

Horsecars were used well into the 1900s to provide rapid transit for beachgoers on Block Island (Sanford Neuschatz Collection)

In his annual address of 1864, Providence Mayor Thomas Doyle discussed the topic of horsecars in some detail. He admitted balancing the city’s need for new revenue without discouraging industry and transportation. The mayor reasoned that “care should be exercised not to make the restrictions so burdensome as practically to prevent the building of the roads. It will be time enough to impose a heavy tax when it shall be found that their earnings will warrant it.” On the other hand, the mayor demanded a unified railway system rather than a competing web of horsecars enterprises. He threatened to withhold a franchise into the city’s commercial center at Market Square until rails on both sides of the Providence River were completed, “otherwise our citizens in passing from one point of the city to the other will be subjected to a change of cars, additional fare and other inconveniences.”

As the mayor spoke, there were seven competing horsecar companies in the nation’s smallest state. William and Amasa Sprague, political and financial dominoes in Rhode Island, orchestrated a merger. The legislature passed the incorporation of the Union Railroad in 1865. Over the next thirty years, this one horsecar company would provide a rudimentary but valuable service between suburban villages and Providence.

[Banner image: Mount Pleasant horsecar #253 photographed on Academy Avenue in Providence about 1890 (Collection of R. L. Wonson)]