Rhode Island’s role in the American Revolutionary War that raged from 1775 to 1783 is wide-ranging and complicated. It is yet another example of how Rhode Island’s history is way more impressive than its small size. This article is intended to simplify the story of Rhode Island’s role by breaking it down into four stages:

1. War Begins and Captain Wallace Terrorizes Narragansett Bay (April 1775 to April 1776).

2. The Privateering Rage (January 1776 to June 1778).

3. The British Occupy Newport and the Rest of Aquidneck Island (including the Battle of Rhode Island) (December 1776 to October 1779).

4. The French Occupy Newport (July 1780 to August 1781).

1. War Begins and Captain Wallace Terrorizes Narragansett Bay (April 1775 to April 1776)

War broke out at the battles of Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts on April 19, 1775. At the battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775, British soldiers finally overran the defenders atop Breed’s Hill outside Boston, but not before suffering horrendous casualties. Patriot forces, including some Rhode Island soldiers, then set siege to Boston, surrounding it. Rhode Island’s newly re-elected governor, Joseph Wanton, a wealthy Newport merchant with Loyalist (Tory) sympathies, refused to sign the commissions of officers of soldiers ready to rush to Boston’s aide. Wanton was formally deposed by the General Assembly in November 1775 and replaced by the newly-elected deputy-governor, Nicholas Cooke of Providence.

Stephen Hopkins of Providence was one of two signers of the Declaration of Independence for Rhode Island. He served as governor of the colony for many terms and pushed the General Assembly to enact antislavery legislation, along with Moses Brown of Providence and Samuel Hopkins of Newport (no relation) (Brown University Portrait Collection)

Once war broke out in April 1775, Rhode Island officials came to realize that its governmental structure was not well organized to supervise Rhode Island’s war effort. First, the governor had relatively little power and a small executive staff. Second, the General Assembly, while it passed an impressive number of acts in support of the war effort, met relatively infrequently, given the colony was at war. In addition, it was cumbersome for the many members of the General Assembly to address the numerous minute details that needed to be attended to in conducting a war. Rhode Island established a “recess committee” to meet and address war measures when the General Assembly was not in session. Consisting of the governor and often less than ten political leaders, the recess committee was able to focus on the details of running a war better than the General Assembly could do. The Recess Committee later transformed in the Council of War, shortly after the British occupied Newport in December 1776.

The smallest colony, Rhode Island, with a population of 60,000, quickly responded to the events of Lexington and Concord, sending a brigade of three regiments and some artillery under Nathanael Greene to Boston. Most of these troops were eventually incorporated into the newly-established Continental Army, with Greene appointed as one of its brigadier generals. Greene, booted out of the Society of Friends in Rhode Island for studying military history and war, would eventually rise to become George Washington’s most valuable subordinate and probably the outstanding strategic commander on either side of the war.

Nathanael Greene, with his homestead in Coventry, was appointed by the General Assembly to command Rhode Island troops in the 1775 siege of Boston. He quickly became a favorite of General George Washington and was promoted to major general. Many argue he was the best tactical general on either side of the war. Painted by Charles Wilson Peale (Independence Hall)

Late in 1774, the British sent the 24-gun frigate Rose, under Captain James Wallace, to patrol Narragansett Bay to try to enforce British tax and maritime laws. The first stage of the war commenced once war broke out in April 1775. Wallace dominated Narragansett Bay, spreading terror among coastal residents until his ships departed. His men torched houses on Jamestown (killing one resident), bombarded Bristol (a minister died of a heart attack), threatened to destroy Newport, and mounted raids to take livestock from farms at Point Judith, North Kingstown and Prudence Island (where a small battle occurred). Finally, Wallace departed Narragansett Bay in April 1776.

2. The Privateering Rage (May 1776 to June 1778)

The second stage of the war in Rhode Island was dominated by America’s most effective weapon at sea—privateering. Privateering was not piracy—privateers were commissioner to fight enemy ships at sea by a state or the Continental Congress. It was the operation of privately-owned commerce raiders for private gain. The officers and crew of a privateer signed “articles” prior to the voyage setting forth each man’s percentage share of the captured cargo, minus costs, that would be paid to him. While privateering in Rhode Island began in January 1776, Rhode Island enacted its own legislation authorizing privateers in March 1776.

Providence, Newport, and Bristol merchants, as well as those in smaller coastal harbors, made the transition to investing in privateers and hiring their former crews as privateersmen. In 1776, they were spectacularly successful, hauling in large British merchant ships from the Caribbean and supply ships off the Canadian coast at a time before the Royal Navy began to protect British commerce. John Howland returned to Providence in early 1777 grueling service as a private in a Rhode Island regiment with Washington’s army. He recalled, “The year 1776 was mostly employed in privateering, and many whom I had left in poor circumstances were now rich men.” Howland recalled that “the wharves in Providence were lined two or three deep with the largest ships from Jamaica . . . .”

John Brown and other former Rhode Island merchants became fabulously wealthy from privateering. One voyage could easily bring in a captured British merchant ship whose value and cargo were worth multiple times the value of the privateer vessel and the costs of the privateering voyage.

A replica of the Continental Navy sloop Providence, which was once commanded by the daring John Paul Jones and once sailed in a fleet under the command of Esek Hopkins of Providence. The author had the privilege of sailing on this replica in Narragansett Bay in 1977 (Heritage Harbor Foundation)

The first commander-in-chief of the Continental Navy (Providence’s Esek Hopkins, who was later fired by the Continental Congress) and the Continental Navy’s greatest war hero, John Paul Jones (when he was in Newport), both decried that so many sailors were signing up for privateers that they could not enlist sailors on their ships. But privateers did add military supplies and wealth to the American cause.

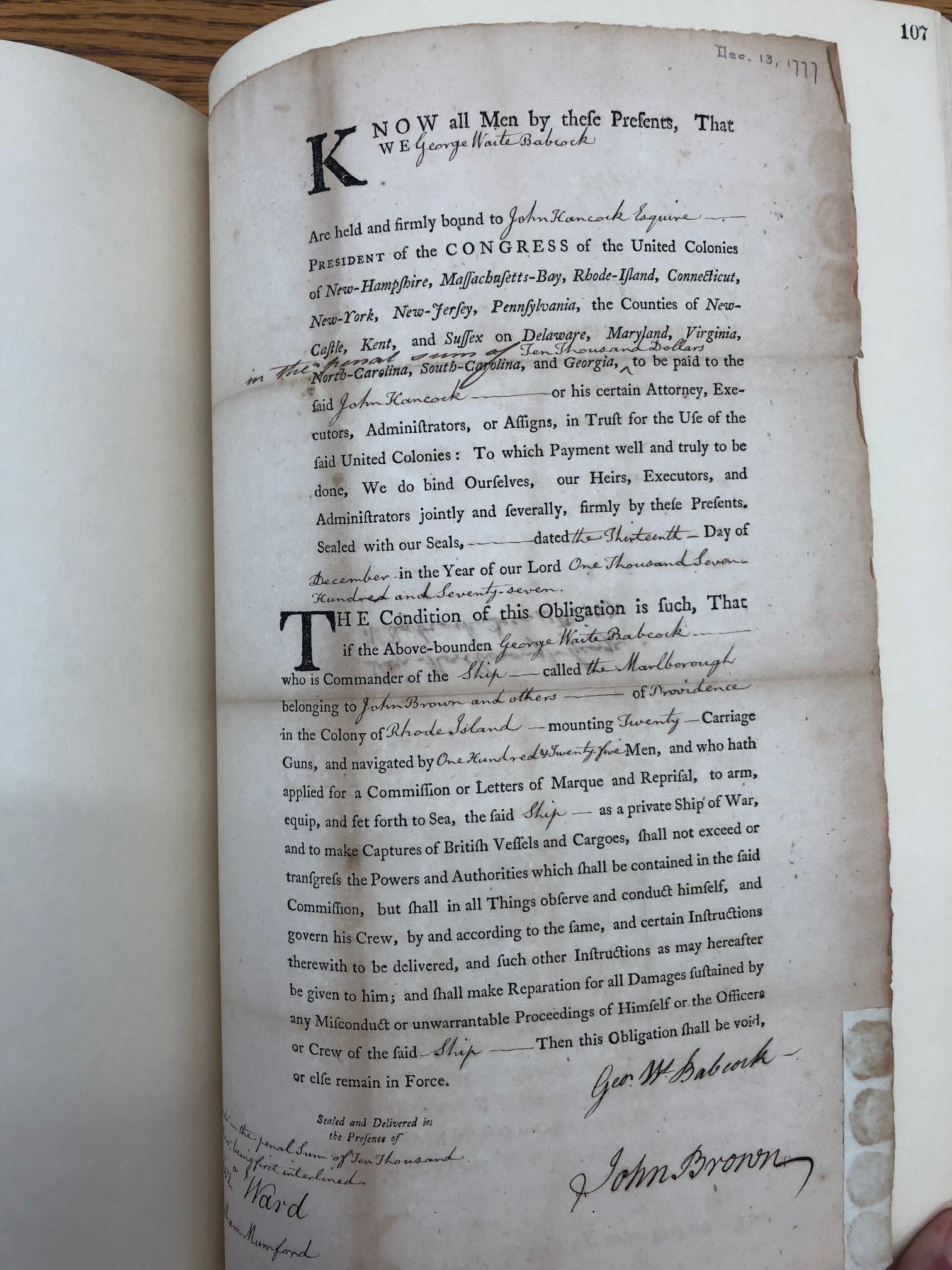

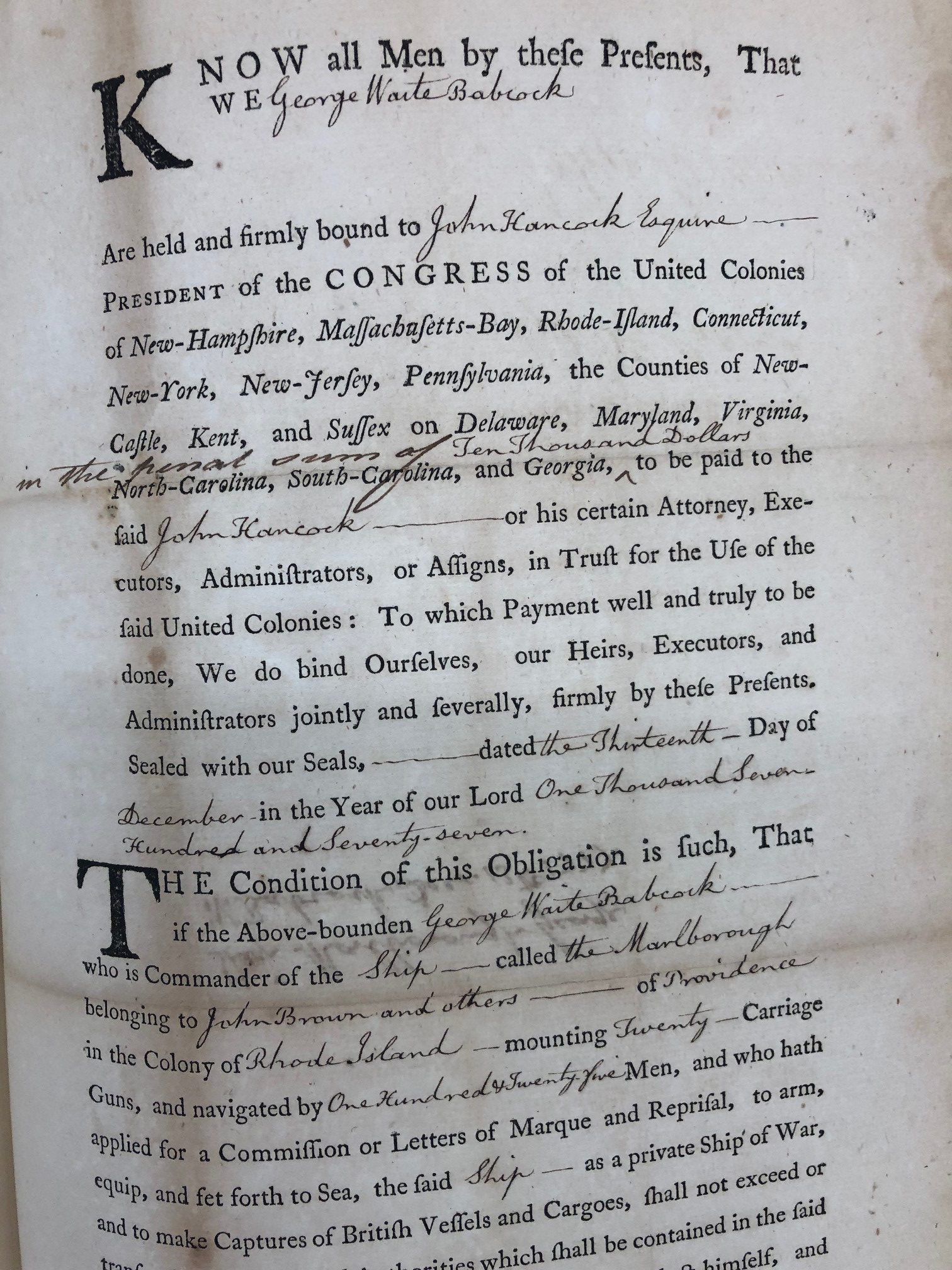

My recent book, Dark Voyage: An American Privateer’s War on Britain’s Slave Trade (Westholme, 2022) is a fascinating microhistory of the Rhode Island privateer Marlborough that in late 1777 and early 1778 sailed from Rhode Island to the coast of Africa and attacked a British slave trading post and British slave ships. At the time, Britain was the world’s leading slave trading country. The book further details for the first time other American privateers capturing numerous British slave ships just before they reached their destinations in the Caribbean, with the consequence of seriously disrupting and virtually halting the British slave trade during the war years. On the other hand, the American privateers, in selling their captured human cargo, in effect became slave traders themselves. This is a ground-breaking book that tells a story of the Revolutionary War never before told.

The privateer commission for the privateer Marlborough, signed by its main investor, John Brown of Providence, and by its captain, George Waite Babcock of Exeter and North Kingstown. The commission, on a form provided by the Continental Congress, indicates that the Marlborough was meant to carry 20 cannon and have a crew of 125 officers and sailors (Christian McBurney, from the Rhode Island State Archives)

This is also very much a Rhode Island story. The main investor and mastermind behind the voyage was Providence merchant John Brown. With his experience in investing in two prior slave voyages, Brown had the boldness, knowledge and expertise to send his new privateer to Africa. The Marlborough was built in Providence. Most of the officers and crew hailed from North Kingstown, Exeter and other Rhode Island towns. The main source for the story is a ship’s log written by John Linscom Boss of Newport.

3. The British Occupy Newport and the Rest of Aquidneck Island (including the Battle of Rhode Island) (December 1776 to October 1779)

In the early part of the war, Rhode Island had not experienced much of the war directly, but that situation dramatically changed in late 1776.

On December 8, 1776, with a fleet of 71 ships and 7,100 soldiers on board, the British seized Newport without difficulty. Lord Richard Howe, the commander of the Royal Navy, wanted an ice-free port in which his large navy could spend the winter. General William Howe, the commander of British army forces in North America, wanted to use Newport as a base for striking at Providence and then retaking Boston. But Howe never received enough reinforcements to act offensively from Newport. Thus, his capture of Newport was of dubious military significance. Thousands of British troops wasted three years of the war in Newport mainly in a defensive posture.

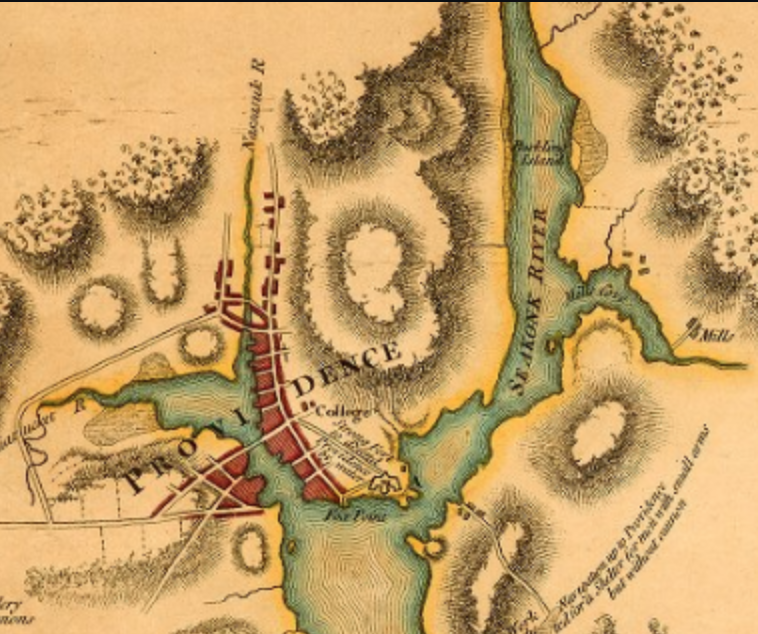

Map of Providence early in the war, by a British cartographer, Charles Blaskowitz, 1777. The British thought about invading Providence after capturing Newport in December 1776, but dropped the effort. (John Carter Brown Library)

The British army, led by Major General Henry Clinton, captured not only Newport, but the rest of Aquidneck Island. Clinton also seized Conanicut Island (the town of Jamestown), since artillery from its coast could reach the channel leading to Newport Harbor. Clinton considered, but ultimately declined, to raid Providence. Thus, the rest of Rhode Island, nearly three-quarters by population, remained firmly in the Patriot camp. British warships set up a blockade of Narragansett Bay, not allowing any American ships in or out of the bay.

Providence’s Esek Hopkins, the commodore of the newly-established Continental Navy until his removal in January 1778, had five of his warships bottled up in his home port. Four of them chose dark and stormy nights to slip out of Narragansett Bay and successfully avoided capture. The 28-gun frigate Providence, commanded by Providence’s Abraham Whipple, even managed to fire broadsides at British ships stationed in the bay. But the 30-gun frigate Columbus was chased ashore on Point Judith and burned in March 1778.

American forces scored some naval successes as well, mainly due to Royal Navy mistakes. When the 32-gun frigate HMS Diamond accidentally grounded itself off Warwick in January 1777, local militia brought up artillery pieces and fired at the helpless ship. But due to poor shooting, a lack of aggressiveness and a rising tide, the Diamond escaped (but it did sport several new holes in its hull). On November 6, 1777, in rough weather, the 28-gun HMS Syren ran aground near Whale Rock on the Narragansett shoreline. This time the local militia brought up three artillery pieces that fired accurate shots. The Royal Navy captain surrendered his frigate, allowing the Americans to gain the captain and 136 British sailors and marines as new captives who could be traded for American prisoners held by the British in Newport.

For the next three years, the General Assembly and the newly-established Council of War passed resolutions to increase the state’s defenses against possible raids by the British army in Newport. The Council of War engaged in the unglamorous but necessary task of logistics—making sure the state’s soldiers had sufficient food, uniforms, blankets, weapons, ammunition and other warlike supplies. It was always a struggle for the state. The General Assembly somewhat increased taxes on residents to help support its troops. But with the British occupying about one-quarter of the state, including the state’s largest city and port, Newport, and blockading Narragansett Bay, the beleaguered residents suffered economic hardships and struggled to pay what taxes were due.

The Old Colony House in Newport. General Assembly meetings were held here, and the Declaration of Independence was read from a balcony in early July 1776. As with many other buildings during the British occupation, it suffered abuse. Reportedly, British officers rode horses in it and kept horses in it as stables. (Providence Public Library Digital Collection)

One of the outstanding events during the British occupation was the brilliant and bold abduction of Major General Richard Prescott, the commander of British troops on Aquidneck Island, by state troops led by Lieutenant Colonel William Barton of Warren and Providence. Barton seized Prescott so that the Americans could have a British officer of the same rank to exchange for Major General Charles Lee, George Washington’s second-in-command. He had been captured by the British in a raid at Basking Ridge, New Jersey, in December 1776. On the night of July 10, 1777, Barton and his party of 48 men rowed their boats at night from Warwick Neck through British warships stationed in Narragansett Bay, quietly made their way for one mile from the coast on British-held Aquidneck Island, surrounded a farm house, captured the sole British army sentry standing guard, snatched General Prescott from his bed, and returned to Warwick Neck safely, all without a shot being fired. As I argue in my book, Kidnapping the Enemy, The Special Operations to Capture Generals Charles Lee & Richard Prescott (Westholme, 2014), Barton’s raid still stands as one of the most impressive special operations in American military history.

In January of 1777, John Adams wrote to his wife Abigail, “The little nest of hornets in Rhode Island [meaning the British army] – is it to remain unmolested this winter? The honor of New England is concerned. If they are not crushed I will never again glory in being a N.E. man.” New England made two attempts to recapture Newport in 1777, but both failed. The second and most serious attempt, called Spencer’s Expedition, named after the first commander-in-chief of the Rhode Island theater of war, Joseph Spencer, was designed as a secret expedition. Without the ability to control the waters around Aquidneck Island, New England militia would rely on the element of surprise. Ordinary soldiers who were drafted were not told where they were going. Suddenly, some 10,000 Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut and New Hampshire militiamen, more than would ever appear in the state during the war, were in Tiverton ready to launch an invasion of Aquidneck Island. But the Americans lost the element of surprise due to various factors, including a British spy based in Providence who escaped to Aquidneck Island in the nick of time to inform British commanders of the planned invasion. Therefore, Spencer’s Expedition was called off.

The Council of War supported the two expeditions, and continued to bolster the state’s defenses by creating two state regiments and raising more militia regiments. The soldiers in these regiments patrolled Rhode Island’s long coastline and were ready to participate in any future invasion of Aquidneck Island.

Meanwhile, the British in Newport confined Patriot prisoners and others suspected of sympathizing with the “rebels” on dank and dirty prison ships in Newport Harbor. Many of them were American sailors captured on board privateers. There were times when, suffering from poor food, mixing of diseased prisoners with healthy ones, and steaming hot conditions, the death rates on board the prison ships spiked.

Matters changed radically when France formally announced its alliance with the United States and declared war on Great Britain in February 1778. The new British commander-in-chief in North America, Henry Clinton, abandoned Philadelphia in order to focus his defenses on two occupied port cities, New York and Newport. The British commander in Newport, Robert Pigot, launched a preemptive raid against the towns of Bristol and Warren, destroying shipping that could have been used to transport American troops to Aquidneck Island, but also burning down dozens of homes and a church as well.

On July 29, 1778, a large French fleet under Charles Henri Theodat, Count d’Estaing, arrived off Point Judith. Britain’s ancient rival, France, had finally decided to openly support the American cause with significant military force. The arrival of d’Estaing’s squadron spread panic among British army and navy forces in Newport.

Not wanting to have their warships at or around Newport captured by the British, the Royal Navy scuttled or blew up six frigates, each carrying from 28 to 32 guns, as well as two sloops and two armed galleys. Taken together, this loss of warships, carrying in total 210 cannon, was the most significant loss suffered by the British navy in the entire Revolutionary War. This fact has not been adequately appreciated, since the ships were not lost as a result of combat. But a loss is a loss, regardless of its cause.

British defenders also scuttled five or six transport ships in between Goat Island and Coasters Harbor Island and six more between Goat Island and Rose Island. The tops of masts protruding above the water’s surface discouraged d’Estaing from sailing into Newport Harbor. One of the sunken transports, the Lord Sandwich, had been used as a British prison ship in Newport Harbor. Previously, when named Endeavour, it had carried Captain James Cook and his crew on its voyage of discovery to Australia and New Zealand from 1768 to 1771. D. K. (Kathy) Abbass, leader of the Rhode Island Marine Archeology Project, reported that she may have found the ship’s remains in Newport harbor.

Meanwhile, the invasion attempt was postponed as the American army took its time to gather a strong force. The Rhode Island General Assembly and Council of War labored to put Rhode Island troops in the field with the proper arms and supplies. Despite impressive efforts, the New England states could not raise the overwhelming force they needed.

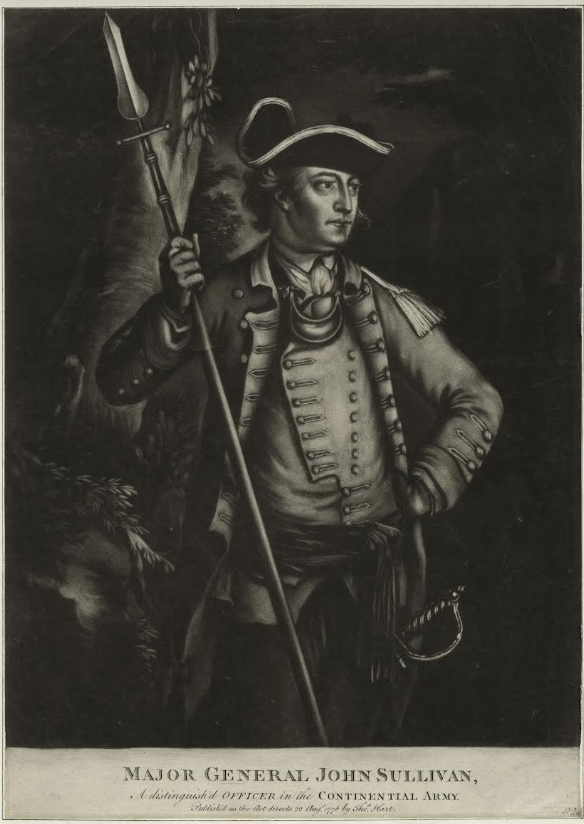

On August 9, the French were finally preparing to ship their troops to the west side of Aquidneck Island. American troops commanded by Major General John Sullivan of New Hampshire already had crossed over from Tiverton and landed on the northeast side of Aquidneck Island the previous day. Just as d’Estaing was about to issue his orders to his men to take to their boats, Admiral Richard Howe’s fleet arrived unexpectedly from Newport to wreck French and American invasion plans.

Major John Sullivan of New Hampshire, commander of the army in Rhode Island during the Siege of Newport and the Battle of Rhode Island in August 1778 (Library of Congress)

D’Estaing decided to leave Narragansett Bay and chase after Howe’s fleet, which sailed away to the southward. The next day, as the French fleet prepared to give battle, a terrible storm (probably a hurricane) separated both fleets. For two days, each ship tried to ride out the storm. The French fleet ended up more damaged than the Royal Navy’s warships. Three major French warships lost their mainmasts and another was missing (it was later learned it had sailed to Boston). Three ships were damaged in battles with British warships. D’Estaing decided to end the attempt to conquer Newport and to retreat to Boston to repair his battered ships.

During this time, General Sullivan set siege to Newport, inching closer to Pigot’s defensive fortifications and pounding them with cannon brought over from the mainland. However, without French navy and army assistance, his force lacked the firepower and forces necessary to overrun the strong British positions.

Sullivan was aided by troops from George Washington’s main Continental Army, and some of its top officers, including Rhode Island’s own generals, Nathanael Greene and James Mitchell Varnum. The French volunteer, the Marquis de Lafayette, also was present in the siege, as were Paul Revere and John Hancock from Massachusetts.

Sullivan learned that British general Henry Clinton was gathering a substantial force of warships and British troops at Long Island, with the intent of arriving in Narragansett Bay and trapping Sullivan’s army on Aquidneck Island. In response, Sullivan ordered his army to retreat on the night of August 28 to the northern part of the island, which it successfully did. Sullivan created a defensive line across the island, anchored at the Butt’s Hill fortification in Portsmouth.

The next morning, British general Pigot decided to attack, hoping to catch the American army as it retreated off the island. Pigot sent some 1,100 British regulars up the East Road and 1,800 German and Loyalist regulars up the West Road.

On the East Road, at the intersection of what is now Union Street, where the Portsmouth Historical Society is now located, a small advance unit of Massachusetts state troops and Rhode Islanders, hiding behind a stonewall, ambushed the British 22nd Regiment. This was one of the great American ambushes of the war. American advance troops also put up a strong resistance to the north at Quaker Hill. But the American advance troops were overwhelmed by the oncoming British troops who outnumbered them and so they retreated to the main American line on the east side of the island commanded by Brigadier General John Glover of Marblehead, Massachusetts. Pigot’s soldiers marched up to the defensive positions, but seeing the American troops remain firm behind stonewalls, and recalling the carnage he witnessed at the Battle of Bunker Hill, Pigot ordered his troops to halt.

Meanwhile, on the West Road, a small party of advance troops led by Lieutenant Colonel John Laurens of South Carolina engaged in a delaying action. But the more numerous German and Loyalist troops continued up the road until they came to the main American defenses. The outer redoubt was held by the famed First Rhode Island Regiment of Continentals, consisting of mostly freed Rhode Island slaves and other men of color. Despite the fact that this was their first battle and that they had not been allowed to train with the militia in prior years, they fought bravely. Three times the German and Loyalist troops tried to storm the American lines, and each time they were driven back. In the last attempt, Major General Nathanael Greene fed a Continental regiment into the battle at a key moment. The charging solders turned the tide of the fighting and forced the attackers to retreat from the field, leaving their dead behind them. The battle was over. The Americans had fought effectively against British, German, and Loyalist regulars; and the British Army suffered more casualties, 260 to 231.

The night after the battle, Sullivan’s army successfully retreated off Aquidneck Island. The Rhode Island Campaign had ended in failure for the new allies. But the Americans, at least, could be pleased with the performance of its army at the Battle of Rhode Island. The entire army had gotten off the island safely. Rhode Island historian Patrick T. Conley has called it Rhode Island’s “Dunkirk.”

The remaining portion of the British occupation of Aquidneck Island and Jamestown, from September 1778 to October 1779, was not as eventful as the first part. Governor William Greene and the Council of War feared more raids, and drafted troops to defend Providence and other parts of the state. The First Rhode Island Regiment remained to defend the state. But the British did not again venture out with a large force.

Still, small raids were not infrequent. A small Tory fleet operating out of Newport, led by George Leonard, made some forays onto the Rhode Island mainland, including one that resulted the capture of eleven soldiers from the First Rhode Island Regiment. On the American side, Silas Talbot of Dighton, Massachusetts, who had moved to Providence, commanded an armed galley that captured the British armed galley Pigot anchored in the Sakonnet River on October 28, 1778. Talbot later captured a feared Loyalist privateer, captained by Rhode Islander Stanton Hazard.

Because of the lack of food and supplies provided to Continental and other soldiers, at least nine mutinies erupted in the Rhode Island theater of war from September 1778 through July 1779. The most dramatic one occurred with the July 1779 mutiny in the Second Rhode Island Regiment of Continentals.

Fearing another attack by Admiral d’Estaing and his ships as they returned from the Caribbean, General Clinton ordered the British army to evacuate Rhode Island. The British withdrawal was effected in mid to late October 1779. In departing, the British did not burn or loot Newport. But in feeding and supplying the troops for almost three years, British soldiers, desperate for firewood, virtually denuded Aquidneck Island of its trees and fences, and had torn down many houses in Newport, especially those abandoned by their Patriot owners. In many ways, Newport never recovered.

Major General Robert Pigot commanded the British army during the Siege of Newport and the Battle of Rhode Island in August 1778. Painted by Francis Coates, 1765 (Wikipedia)

The departing ships contained dozens of formerly enslaved Rhode Islanders. While hundreds of black men in Rhode Island served in the Continental Army regiments, state regiments, and militia, and gained their freedom in doing so (if they survived the war), other enslaved men, women and children adopted a different route. They took the opportunity to flee to Newport. They then departed on British ships to New York City and, after the war, to freedom in Canada.

4. The French Occupy Newport (July 1780 to August 1781)

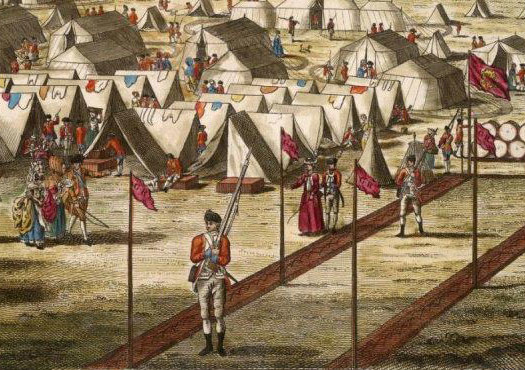

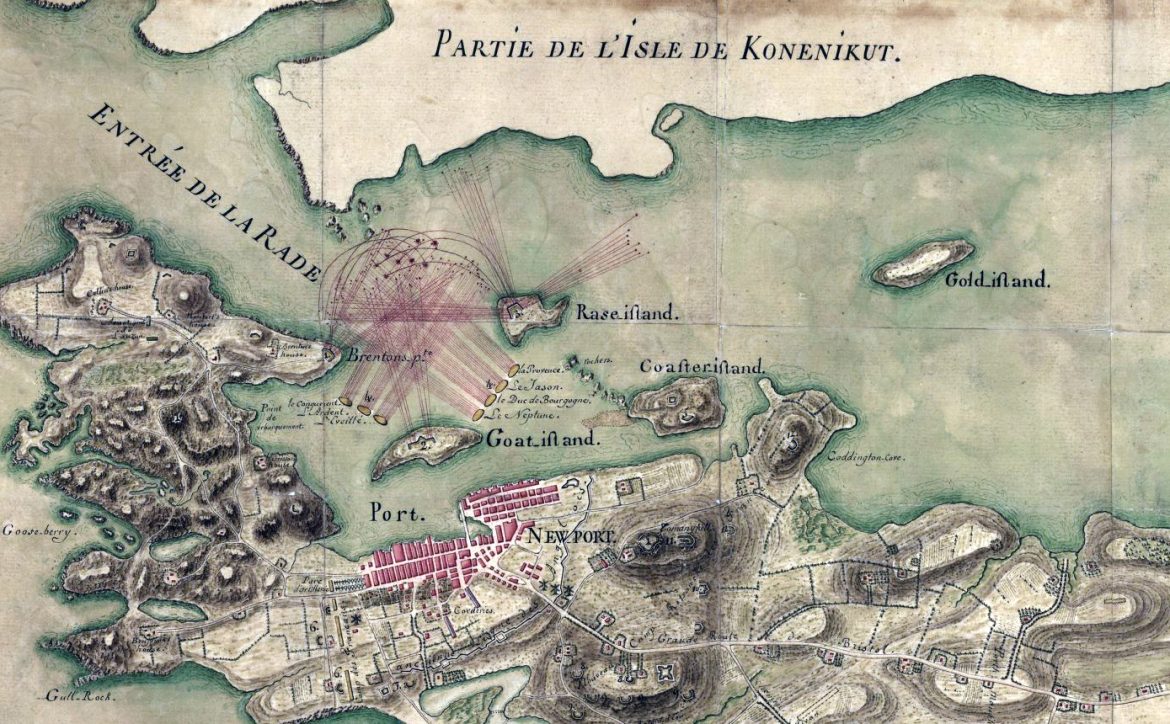

The fourth stage of the war was another occupation of Newport, but this time it was by allies, the French army. On July 10, 1780, a French fleet carrying some 6,000 French soldiers commanded by Lieutenant General Comte de Rochambeau arrived off of Newport. Rochambeau intended to use Newport as the primary base of French operations in the United States. Meanwhile, General Clinton felt that if the combined forces of the British navy and army could attack Newport after the French arrived, but before they established their defenses, they could gain a crushing victory that might take France out of the war. Therefore, he made plans to invade Aquidneck Island and defeat the French military forces. American spies, including those working in the famed Culper spy ring, alerted Rochambeau to the gathering expeditionary force. The General Assembly and Council of War then drafted more militia to join state troops on Aquidneck Island, helping to defend against the expected attack. Clinton never mounted an attack, due to a dispute with the new commander of the Royal Navy and to reports of his own spy in Newport of the increased defenses in Newport Harbor.

Now the French looked for an opening to send its troops and artillery based in Newport to attack the British. They made two attempts, the last in March 1781, but they failed. The British navy had been tipped off about the March 1781 attempt by a Newport Loyalist spy. Each time, the Rhode Island General Assembly and Council of War were asked to raise Rhode Island militia regiments to defend Aquidneck Island in case of British attack. Fortifications on Aquidneck Island, including at Butts Hill, were improved.

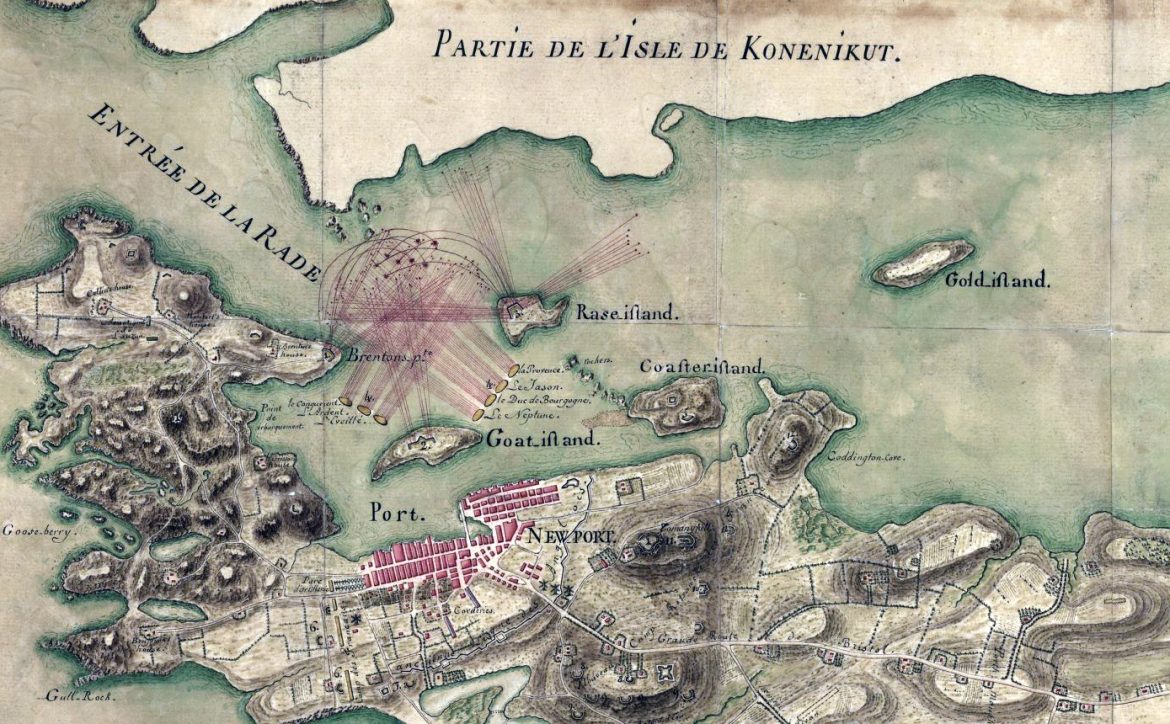

French map showing the French defenses of Newport, after the French occupied Newport in July 1780. The British commander-in-chief Henry Clinton considered attacking Newport at this time but due to confusion in the British high command, it did not occur (Library of Congress)

General George Washington travelled to Newport in March of 1781 to meet with the Rochambeau, Admiral Destouches, and all the senior French officers just prior to the departure of the French fleet for the Chesapeake. Washington was greeted in Newport by an artillery salute as he stepped off the Jamestown ferry on March 6. French troops lined both sides of parts of the path to Rochambeau’s headquarters. Newport’s political leaders were so excited about Washington’s visit that the town council even furnished free candles so that windows in public buildings and private homes in the city could be illuminated in his honor (some Tories who did not comply had their windows broken with rocks).

The French occupation of Newport was complicated. The Newporters appreciated that the French were allies and loved the hard money the French paid, but did not like the inflation that arose from competition for scarce supplies and the thousands of French army troops that roamed in Newport and on Aquidneck Island.

In June 1781, Rochambeau marched most of his troops, in two divisions, from Newport to the southward, ultimately ending up at Yorktown, Virginia. The troops first embarked on French ships that landed them in Providence, where they encamped from June 12 to 22, and then marched west across the state. On August 23, Admiral Barras and his nine ships departed Newport with the artillery train, along with 480 French infantrymen and 130 artillerists, for Yorktown, Virginia, where Rochambeau had arrived. A contingent of 104 French infantrymen went from Newport to Providence to protect that city. Thus, the French had fully evacuated Newport. More Rhode Island militia were called out to defend Newport. In Virginia, the combined American and French force at Yorktown, under Generals Washington and Rochambeau, forced the surrender of a major British army under Lord Charles Cornwallis in October 1781.

The comte de Rochambeau, commander of the French army in Newport from July 1780 until his departure for Virginia in June 1781 (Wikipedia)

While the surrender of Yorktown eventually led Great Britain to end the war and recognize the United States’ independence, that result would take time—more than a year. Congress did not ratify the Treaty of Paris that formally ended the war until May 12, 1784. Meanwhile, the Council of War continued until at least April 24, 1782, working on supplying Rhode Island’s troops in the field. The French army, on its return march to Boston, encamped in Providence in November 1782.

During all four stages of the war in Rhode Island, first the General Assembly, the Recess Committee and then the Council of War, and local town governments addressed a common topic: identifying and punishing Tories, and sometimes banning their return and confiscating their property. (Loyalists (also called Tories) wanted to remain under Crown rule.) Many Loyalists descended from Rhode Island settlers from the seventeenth century. This was a controversial and ugly topic in Rhode Island.

Main Sources

For the invasion of the British of Rhode Island in December 1779, Spencer’s Expedition, the British raids of Bristol and Warren, the Rhode Island Campaign, and the Battle of Rhode Island, see Christian McBurney, The Rhode Island Campaign, The First French and American Operation in the Revolutionary War (Westholme, 2011) and the sources cited therein. This book has more than one thousand footnotes, most of them to original sources.

For the capture of General Prescott, see Christian McBurney, Kidnapping the Enemy: The Special Operations to Capture Generals Charles Lee & Richard Prescott (Westholme, 2014).

For privateering in Rhode Island, see Christian McBurney, Dark Voyage: An American Privateer’s War on Britain’s African Slave Trade (Westholme, 2022), particularly chapter 2 on privateering, and chapters 6 through 8 on the Marlborough’s actions on the African coast, as well as sources cited therein.

For material on the Battle of Monmouth, see Christian McBurney, George Washington’s Nemesis, The Outrageous Treason and Unfair Court-Martial of Major General Charles Lee during the Revolutionary War (Savas Beatie, 2020), particularly chapter 8, “Lee in Command,” and chapters 10 and 11, on the court-martial of Lee.

For the French in Newport, see the many articles by Norman Desmarais on the topic in the online Review of Rhode Island History, at www.smallstatebighistory.com (search for in the French in Newport, 1780-1781 category), particularly “Why Newport Scorned the French in 1780” and “French Soldiers Who Died at Newport During the Revolutionary War.”

For Captain Wallace terrorizing Narragansett Bay, see Michael R. Derderian, “Maritime Skirmishes in Narragansett Bay, 1763-1769, and Robert Grandchamp, “Rhode Island Militia Battles the Dreaded British Captain James Wallace on Prudence Island,” in the online Review of Rhode Island History, at www.smallstatebighistory.com (search for in the American Revolution and Revolutionary War category).

For American navy successes in 1777, see Christian McBurney, “’Strange Mismanagement’: The Capture of HMS Syren,” April 10, 2014, in the online Journal of the American Revolution, at https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/04/strange-mismanagement-the-capture-of-hms-syren/ and at www.smallstatebighistory.com (search for in the American Revolution and Revolutionary War category or for term Syren).

For spying activities undertaken in each of the four stages, see Christian McBurney, Spies in Revolutionary Rhode Island (History Press, 2014) and the sources cited therein.

For the British prison ships in Newport Harbor, see Christian McBurney, “British Treatment of Prisoners During the Occupation of Newport, 1776-1779: Disease, Starvation and Death Stalk the Prison Ships,” Newport History, Vol. 79, No. 23 (Fall 2010), 1-41.

For the spate of munities in the American ranks in Rhode Island in late 1778 and the first half of 1779, see Christian McBurney, “Mutiny! American Mutinies in the Rhode Island Theater of War, September 1778-July 1779,” Rhode Island History, Vol. 9, No. 2 (Summer/Fall 2011), 47-72.

For Blacks fleeing to British-held Newport, see Christian McBurney, “Freedom for African-Americans in British-Occupied Newport, 1776-1779, and ‘The Book of Negroes,’” Newport History, Vol. 87, No. 276 (Summer/Fall 2017), 1-39, and Jane Lancaster, “Should They Stay or Should They Go? Rhode Island Black Loyalists After the American Revolution,” in the online Review of Rhode Island History, at www.smallstatebighistory.com (search for in American Revolution and Revolutionary War category).

For governance in Rhode Island during the Revolutionary War, see John K. Robertson, Proceedings of the ‘Recess’ Committee of the Rhode-Island General Assembly 1775-1776 and the Rhode Island Council of War 1776-1782 (Rhode Island Publications Society, 2018).

For information on many of the above topics, see also D. K. Abbass, Rhode Island in the Revolution: Big Happenings in the Smallest Colony, 4 vols., 2nd ed. (USDI National Park Service, American Battlefield Protection Programs, 2006).