When asked the secret to his longevity, John Henry Riley, II, told his listeners: “Go ahead. Do what you want. But never cross the line of moderation.” [1] Riley certainly lived life to the fullest; as to moderation, he probably told a white lie. He loved a good time, “had a rugged constitution,” and enjoyed his ale especially with friends who always seemed to appear like clockwork when Riley’s pension check arrived by mail. They all departed to visit Jackson Tavern, in Jackson, Rhode Island (an unincorporated town where Riley had built the tavern for another individual). As the story goes, the “boys” travelled to the tavern each day to play cards, smoke, and drink until Riley’s funds were depleted – usually within three days. The fun was over, but not before repeating the adventure when Riley’s next pension check arrived.

According to his great-grandson, Lloyd Lincoln Colvin, his great-grandfather’s demeanor appeared gruff, at least on the surface. Though some were taken aback by the “Old Gent” (that’s what many called him) and his brusque personality, others knew it was just his way. Colvin remembers that as Riley aged, his clothing appeared disheveled and loose fitting. “As a youngster, I used to sit on his lap after dinner and listen to his stories,” Colvin said, adding: “I talked to him a great deal and took a keen interest in everything he had to say about the war.” Colvin especially relished stories about how his great-grandfather saw President Lincoln while stationed in Washington, D.C., and that on one occasion he even got to shake his hand when Lincoln paid a visit to his regiment in camp.

Those who knew Riley said he possessed a remarkable memory throughout his entire lifetime. Colvin remembers that his great-grandfather did not take kindly to General Dan Sickles’s advance toward a wheat field (a.k.a., the Wheatfield) at the Battle of Gettysburg—an unauthorized maneuver that jeopardized the safety of the troops. “He wasn’t very happy about that,” Colvin reiterated. Riley also told his great-grandson that he witnessed Pickett’s Charge, but only from a distance as Riley’s regiment was not directly engaged that day though they were, as written in the state’s adjutant general’s report, “constantly moving under a storm of shells to different parts of the field, in support of points hard pressed.” [2]

John Riley, II, was born in Dover, New Jersey, on June 9, 1841, to parents who emigrated from Ireland. His father had worked the iron mines for a number of years. Riley was only a year old when the family moved to Johnston, Rhode Island. In his youth, he worked at the Morgan Mill in Johnston being paid 75 cents a week. Though he never received much of a formal education (two years of schooling at best), he did learn to read, write, and as Riley himself said, “reckon.”

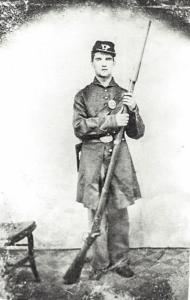

Riley enlisted with Co. H, 2nd Regiment, Rhode Island Volunteer Infantry on February 28, 1863, and experienced quite a bit of fighting in a regiment that had already seen its fair share of combat. Riley wanted to fight, not because he was patriotic, which he was, or that he was a Lincoln Republican – a staunch one at that – but because he wanted to avenge the death of his father, John, mortally wounded at First Bull Run who died four days later in a Richmond prison pen. For the rest of his life, Riley never forgot standing on a sidewalk in Providence watching his father leave for war. Adding to his ill feelings, Riley’s brother was also seriously wounded at Manassas.

After his regiment took part in the Grand Parade at Washington, D.C., Riley was discharged from the service on July 13, 1865. He moved to Scituate, Rhode Island, and worked as a millwright in local mills around Pawtucket Valley where his skills at the trade seemed to be in constant demand. He also worked as a carpenter, a mechanic, a farmer, a steam stationary engineer, and even a stage coach driver.

Working in a mill a few months after his discharge, Riley met Anna Marie Mason originally from Newport, Rhode Island, but living in Arctic (now part of West Warwick, Rhode Island). Their affection for one another was immediate. When his mother found out that her good Irish Catholic son intended to marry a Protestant, she immediately and vehemently protested. Riley was determined to marry her and told his mother that nothing could stop him. Thinking it a grave sin and a serious stain upon the family name, his mother, in a state of rage, threatened to have him killed if he went through with the engagement and wedding. She even went so far as to tell another of her sons to kill him. “I can’t do that,” the brother protested, obviously upset at his mother’s insane proposal. The marriage did take place, however, and eventually produced eleven children. But the animosity continued unabated within the family for years.

Riley was 80 years old when he decided to retire. After his wife, Anna Marie, passed away during the Influenza Pandemic of 1918, he moved to a two room summer house owned by one of his four sons (the chief of police of Scituate). Though he entertained his friends in the smaller house, Riley ate his meals and slept at his son and daughter-in-law’s home next door. He knew not to be an unnecessary burden on the family while maintaining his own sense of independence.

Riley was once a member of the G.A.R., but he let his membership lapse fifty years earlier. But at the age of 100, he was convinced perhaps by outside influences to renew his association with the veterans group.

In his final year, Riley told a newspaper reporter that he was “at peace with the Lord and ready when the time came.” During the last six months of his life, his health had badly deteriorated. His Irish pride never wavered, however. On his deathbed, although gasping for every breath, he whispered in his great-grandson’s ear: “I was the last of 24,000 Rhode Islanders . . . mostly Irish.” When he died at the home of his son, on May 7, 1943, John H. Riley, III, the aged veteran was a month shy of his 102nd birthday.

Riley’s funeral was attended by an estimated 500 people. The coffin in which the body was placed was lifted on a caisson and drawn to the funeral service and then the cemetery by a team of horses. Colvin attended his great-grandfather’s funeral and distinctly remembers the funeral escort that included six Spanish American War veterans, a fife and drum, and a bagpiper. John H. Riley, II, lies at rest at Manchester Cemetery in Coventry, Rhode Island. But the story of John Henry Riley, II, does not end here.

In 2009, Lloyd Lincoln Colvin erected a lasting tribute to his beloved great-grandfather in Hope, Rhode Island. Along with family members, friends and neighbors, Colvin erected a black India granite memorial in his side yard that was placed in the center of a position aptly named Lincoln Circle. Laser etched at the top of the stone is an image of Riley enhanced at the lower level by laser etched artwork of major battles in which he fought including battle descriptors. It might be the only such memorial erected on private property for any of the states’ last surviving veterans. On July 11, 2009, honored guests and state dignitaries joined together to help consecrate the monument. [3]

There are two other veterans from the state worth mentioning. When Edward F. Gillett of Providence died on February 2, 1943, a Rhode Island newspaper erroneously reported that he was the last Civil War veteran from the state. (Actually he was third from the last.) Gillett had served with the 22nd Regiment, Michigan Volunteer Infantry.

Two months later on May 1, 1943, Joseph Thomas Ray died at the age of 96. Had he lived another seven days, he would have unseated John H. Riley, II, as the last Civil War veteran from the state. Born a slave in Virginia, Ray escaped bondage managing to find his way to Newport, Rhode Island, most assuredly via the Underground Railroad. In the spring of 1865, at the age of 18 and living in Bristol (across Narragansett Bay from Aquidneck Island), Ray and a companion trekked to Providence to enlist in the 14th Regiment, Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Colored). But enlistments were closed for that regiment; therefore, Ray joined the 118th Regiment, United States Colored Troops staying with them for over a year in the vicinity of Brownsville, Texas.

Joseph Thomas Ray was the last survivor of Newport’s Lawton-Warren Post No. 5, of the G.A.R. When he died, the post ceased to exist. His funeral took place at Newport’s Mr. Zion African Methodist Church. Ray’s earthly remains were laid to rest in the family plot at Newport’s city cemetery.

__________

A Regimental Brief of Co. H, 2nd Regiment, Rhode Island Volunteer Infantry

For Civil War enthusiasts, the following regimental briefs are provided to highlight Riley’s company and regiment activities before and after his joining the unit. As noted below, when Riley first arrived in the field, he was greeted by seasoned warriors who had fought in several major battles and campaigns during 1861 and 1862.

Activities Prior to Riley joining the Regiment

After being organized at Providence, Rhode Island, in June of 1861, the regiment proceeded to Camp Sprague in Washington, D. C., where it remained until July 16, 1861, before marching to Manassas, Virginia, where it fought in the Battle of Bull Run (July 21). After the Union defeat, the regiment headed back to the District of Columbia and remained there until March of 1862. In late March, the regiment took part in the Peninsula Campaign fighting at the Battle of Williamsburg (May 5), the Battle of Fair Oaks (May 31 through June 1), the Seven Days Battle around Richmond (June 25 through July 1), and Malvern Hill (July 1). After these battles the regiment moved toward Harrison’s Landing where it remained until mid-August. For the next several months the soldiers performed reconnaissance duty while moving throughout Virginia. Then in December, the regiment fought in the Battle of Fredericksburg (December 12 through 15) while also taking part in the infamous “Mud March” a month later.

Activities Riley Participated in after Joining His Regiment in the Field

In the spring and summer of 1863, the regiment participated in two major battles: the Battle of Chancellorsville (April 27 through May 6) and the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1 through 3). In 1864, the regiment fought in more major battles: the Battle of the Wilderness (May 5 through 7); the Battle of Spotsylvania (May 8 through12); and the Battle of Cold Harbor (June 1 through12). Around the middle of June, battle weary veterans whose enlistments were ready to expire were mustered out. From mid-June to early July, the regiment was at Petersburg, Virginia. On the 9th of July the regiment was ordered to Washington, D. C. to help repulse General Early’s attack on the city (July 11 and 12). The regiment eventually returned to Petersburg in early December where it participated in the siege until April of 1865. From March 28 through April 9, the soldiers took part in the Appomattox Campaign where they witnessed the fall of Petersburg. From April 3 through 9 the regiment continued to pursue General Lee’s army. In late May and into early June, the regiment marched to Washington. On July 13, 1865, the regiment mustered out. Over four full years of war the regiment lost 9 officers and 111 enlisted men killed and mortally wounded and 2 officers and 74 enlisted men who died of disease. [4] [Banner Image: Monument dedicated to John Henry Riley, on the property of Lloyd Lincoln Colvin]]

Notes

[1] Providence Journal, May 8, 1943. [2] H. Crandall and A.D.C., Annual Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Rhode Island, for the Year 1865 (Providence, RI: Providence Press Company, 1866), 41. [3] Material for this story was garnered from an interview between Lloyd Lincoln Colvin along with his wife Barbara, and the author on January 15, 2015. [4] See http://www.nps.gov/civilwar/search-battle-units-detail.htm?battleUnitCode=URI0002RI provided by the U.S. National Park Service.