[Editor’s Note: Fittingly, the following biographical entries for these three outstanding architects appear consecutively in Dr. Patrick T. Conley’s The Leaders of Rhode Island’s Golden Age (History Press, 2019). The postcards shown are all from the collection of Sanford Neuschatz.]

Richard Morris Hunt:

Born in Brattleboro, Vermont on October 31, 1877, Richard Morris Hunt had impressive lineage. His mother Jane Leavitt came from a prominent Connecticut family, and his father, Jonathan, was a U.S. congressman whose own father had been lieutenant governor of Vermont. His family antecedents also included Gouvernor Morris of New York, a principal draftsman of the U.S. Constitution.

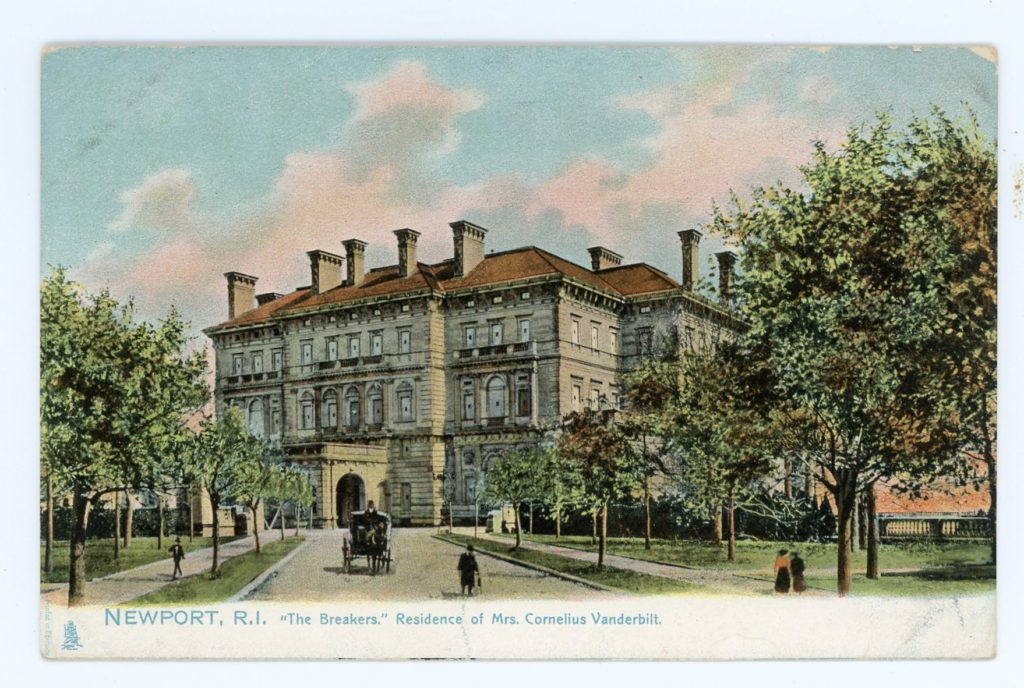

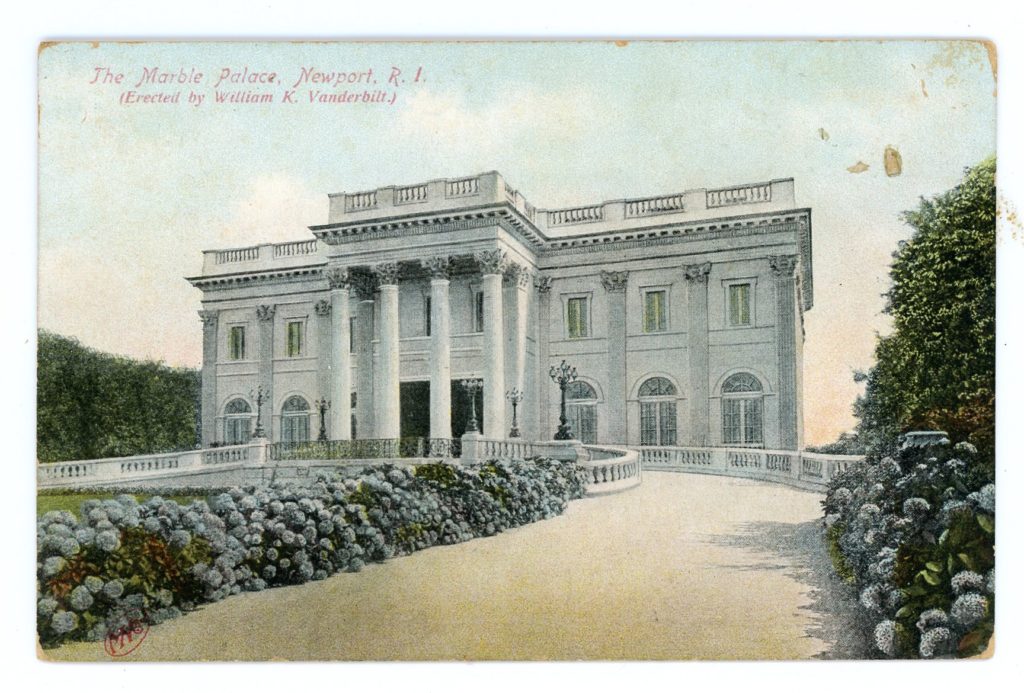

Hunt was the first American to study at the famed École de Beaux-Arts in Paris. He was an accomplished architect in New York, Boston, and Chicago (where he designed the 1893 World’s Fair Administration Building), but it was in Rhode Island that he accomplished most of his enduring masterworks. A favorite of New York City’s rich and famous, Hunt was the architect of their Newport “cottages”–Marble House, the Breakers, Ochre Court, Chateau-sur-Mer, Belcourt Castle, and others.

He was married to Catherine Clinton Howland, a union that provided social entrée to both New York and Newport circles. The Hunts lived in a house they called “Hypotenuse” on what is now the site of the Viking Hotel. One of his first commissions in Newport was the Griswold House (1863-64), now the Newport Art Museum. Hunt was often credited for putting the gilding on the “Gilded Age.” He is also cited for creating the profession of architecture in America.

Hunt formed the famous “Tenth Street Studio” upon his return from France in 1855. It became the training ground for some of the most famous architects in nineteenth-century America. Hunt co-founded the American Institute of Architects and became its third president, from 1888-1891. His advocacy for professional stature led his student William Robert Ware to establish university programs in architecture at MIT in 1866 and at Columbia in 1881.

Besides the spectacular “cottages” at Newport, reminders of Hunt’s work are the base of the Statue of Liberty, the New York Tribune Building, the façade of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (which was finished by his architect son), and many Fifth Avenue mansions. He was a frequent collaborator with America’s premier landscape architect, Frederick Law Olmsted. Their most famous partnership produced the magnificent and huge Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina, which was constructed for George W. Vanderbilt.

Hunt died in Newport on July 31, 1895 at the age of sixty-seven and was buried in the Island Cemetery in his adopted city-by-the-sea. He is the subject of an excellent biography by Paul R. Baker.

Charles F. McKim:

Charles Follen McKim was born in Chester County, Pennsylvania on August 24, 1847. He was the son of an abolitionist father who was also a Presbyterian minister and a Quaker mother. The radical politics of his parents had little impact on McKim. He became a cosmopolitan architect who traveled in the company of wealthy and prominent businessmen and politicians.

After study at Harvard, McKim enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris and traveled throughout Europe. Upon his return to America, he worked in New York City with the famed architect Henry Hobson Richardson. In 1879, he formed a partnership with William Rutherford Mead and Stanford White. This trio became nationally renowned for designing grand public buildings and splendid private mansions.

McKim and his associates were identified with the promotion of classicism as the basis for American public architecture. His firm’s approximately 11,000 individual commissions during McKim’s tenure were mainly from New York City and the Northeast, but the partners designed significant structures in many other states.

After 1887, as both the firm and the projects grew in size and complexity, a single partner would take charge, and the individual hand of each became easier to distinguish. McKim’s dominant motif was the establishment of an architectural imagery appropriate for the United States. The result became known as American Renaissance–an attempt to both emulate and rival Old World culture and artistic standards.

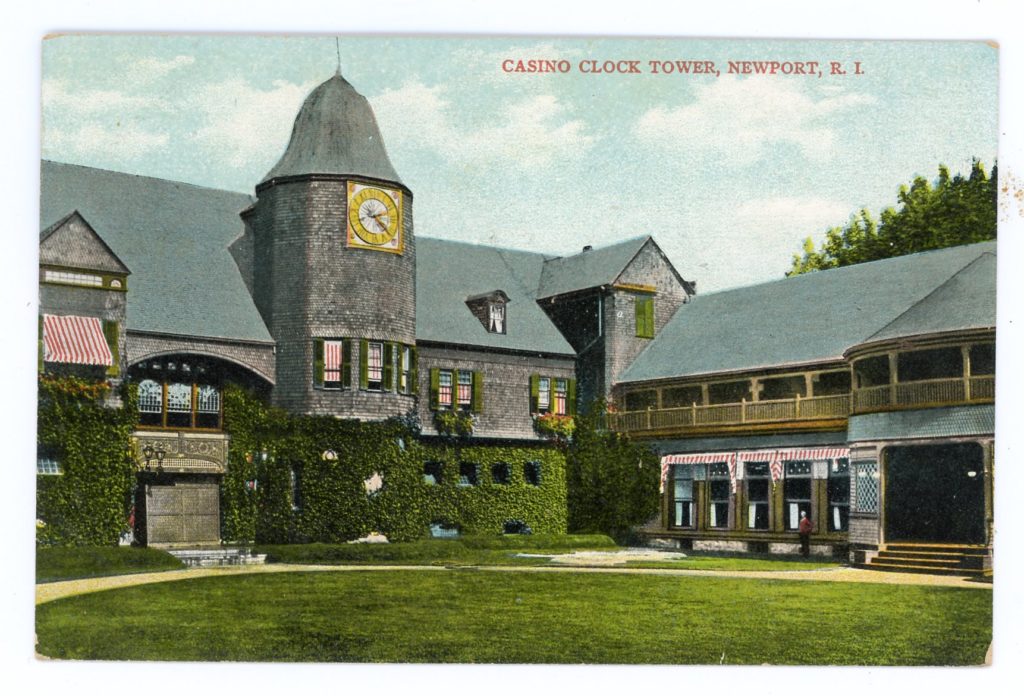

McKim’s strong contacts with Rhode Island began in 1874 when he married Anne Bigelow of New York, the sister of his one-time partner. He spent portions of the next several summers with Anne’s family in Newport before divorcing her in 1879. By that year, he had gained a reputation for designing wooden summer houses in Newport and other East Coast resorts. These commissions dominated his firm’s early work. The partnership’s early shingle-covered structures included such Newport landmarks as its Casino, the Samuel Tilton House, the Isaac Bell House, and Ochre Point. In Bristol, he designed the beautiful (and now demolished) William G. Low house on Bristol Point.

In the late 1880s, McKim moved to the more formal and classical American-Georgian style of the late eighteenth century and then to Greek and Roman classicism, which tended toward austere grandeur. Rhode Island examples of this transition include Newport’s Beacon Rock (1891), and the magnificent Rosecliff, which was built for Hermann and Theresa Fair Oelrichs between 1897 and 1902 on a site formerly occupied by historian, rose horticulturist, and Hall of Fame inductee George Bancroft.

McKim, with the aid of Richard Morris Hunt, was instrumental in the formation of the American School of Architecture in Rome in 1894, now the American Academy. His partnership designed its main buildings.

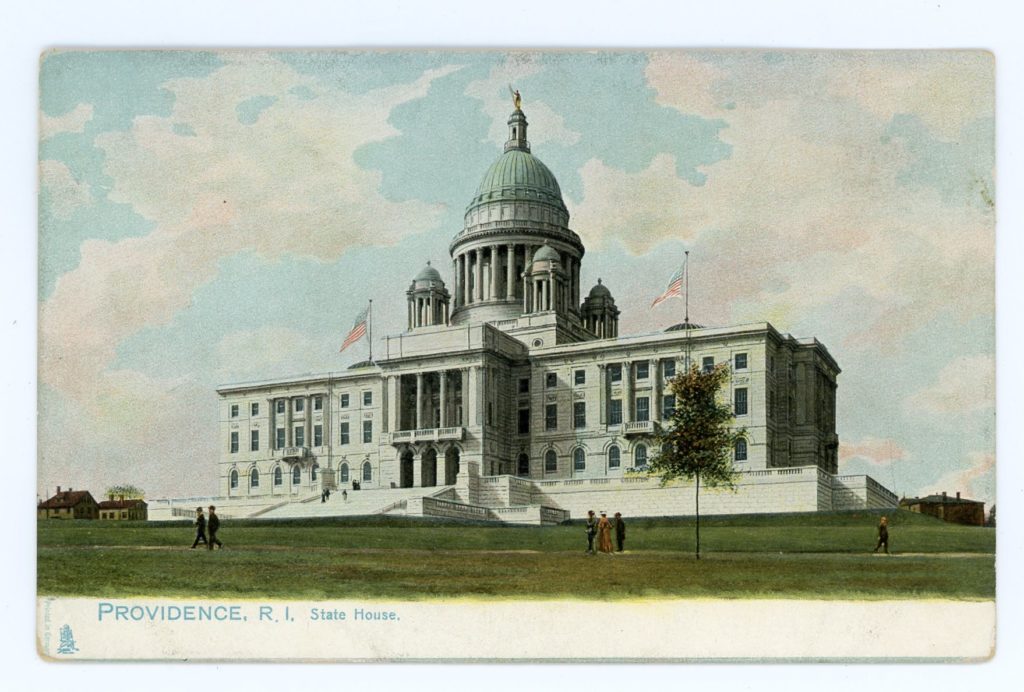

The firm’s crowning Rhode Island achievement was the State Capitol Building constructed between 1895 and 1900 on Smith’s Hill overlooking Downtown Providence. According to one local architectural historian: “What set the Rhode Island State House apart from the other state capitols was . . . the strength and clarity of the architects’ interpretation . . . The success of this abstract design owes a great deal to McKim, Mead & White’s organization of Renaissance-and Georgian-inspired sources into a tight, focused composition . . . More important, the building projected the emerging American Renaissance, a new vision of urban America as the cultural inheritor of Ancient Greece, Republican Rome, and Renaissance Italy.”

Shortly after completion of the State House, McKim was selected by President Theodore Roosevelt to remodel the White House. In 1902-03, he served as president of the American Institute of Architects (AIA), an organization that he helped to transform from a small, New York-based gentlemen’s club into a national organization with political influence that promulgated standards for all American architects. He also received numerous awards and honorary doctorates. McKim died on September 14, 1909 in St. James, New York at the age of sixty-two.

The Princeton Architectural Press released in 2019 a lavishly illustrated 428-page volume titled McKim, Mead & White Selected Works, 1879-1915, featuring the Rhode Island Statehouse, the Newport Casino, the Narragansett Pier Casino, Rosecliff and several other Newport mansions.

Stanford White:

Although he was born in New York City on November 9, 1853, Stanford White found in Rhode Island the perfect social and natural setting for his artistic talents, and Rhode Island found in Stanford White the architectural genius that perfectly captured the spirit of its “Gilded Age”. Whereas one without the other would have been noteworthy, the combination produced one of the greatest epochs in Rhode Island architectural history.

At the age of nineteen, Stanford White began an apprenticeship in the Boston office of Henry Hobson Richardson, the most famous architect of his time. He then studied architecture in Europe, accompanied by his lifelong friend, sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Upon his return in 1879, White entered into partnership with Charles F. McKim and William R. Mead forming the firm of McKim, Mead & White. This trio received major commissions that included New York’s Pennsylvania Station and Madison Square Garden, the Washington Memorial Arch, and the Boston Public Library. The firm also secured several Rhode Island institutional commissions that included the Newport Casino, Narragansett Pier Casino, and the Rhode Island State House, (described in the profile of White’s partner, Charles McKim).

As the most flamboyant, gregarious, and socially mobile member of the partnership, White developed a bevy of high-profile, private residential commissions. Many of his finest examples, done in the distinctive “shingle” and “beaux arts” styles, are still to be admired in Newport. From 1881 to 1891 White, individually or in conjunction with his firm, produced such famous Newport mansions as Kingscote, Ochre Point, Fairlawn, the Isaac Bell House, Sunnyside, and Beacon Rock. From 1896 to 1902, he presided over the construction of the magnificent Rosecliff , which was later chosen as the backdrop for such Hollywood movies as The Great Gatsby, The Betsy, and True Lies.

Even in death, White was sensational. He was murdered on June 25, 1906 at age fifty-two in the Roof Top Supper Club of Madison Square Garden, a facility that he had designed. His killer was millionaire Henry K. Thaw, husband of actress Evelyn Nesbit with whom the womanizing White once had an affair. The press called the ensuing courtroom drama the “trial of the century.” The erratic Thaw was the first defendant to gain acquittal by reliance on the controversial theory of “temporary insanity.”

White has gained lasting fame through his magnificent Rhode Island architectural legacy. He is the subject of a fascinating biography by Paul R. Baker titled The Gilded Life of Stanford White.

[Banner image: While the Marble House in Newport was erected for William K. Vanderbilt from 1888 to 1892, its architect was Richard Morris Hunt. The outside is brick faced with marble (Sanford Neuschatz Collection).]